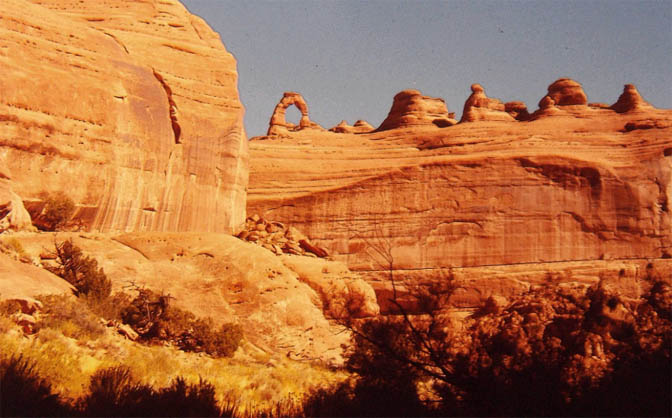

Delicate Arch…the name sounds familiar… it rings a bell. In its online literature the National Park Service at Arches National Park calls Delicate Arch “the best known arch in the world.” In years past, the State of Utah considered the arch “so iconic” that it stamped the arch’s image on all state license plates. Visitation to Delicate Arch has recently become such an event that it is virtually impossible to experience the arch alone, or even with a small group of fellow tourists. The crowds at Delicate Arch resemble a concert mob, or a gathering for some kind of sporting event. Or maybe a really gruesome car accident. Delicate Arch in 2023 is rarely the windswept, solitary rock span that was once known to just a handful of locals.

“When everything is reduced to the mere counter-balancing of economic interests…when Nature has been so subjugated that she has lost all her original forms, what room will there be for virtue?

In the mean time, things are going to get very murky.“

— Gustave Flaubert

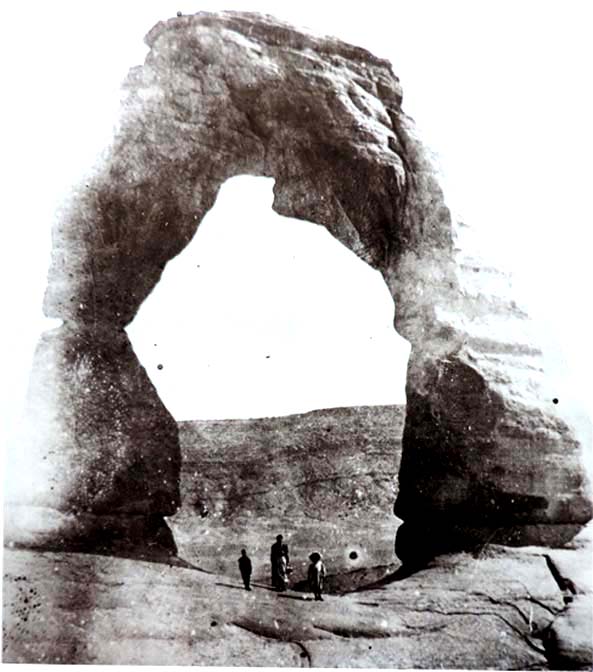

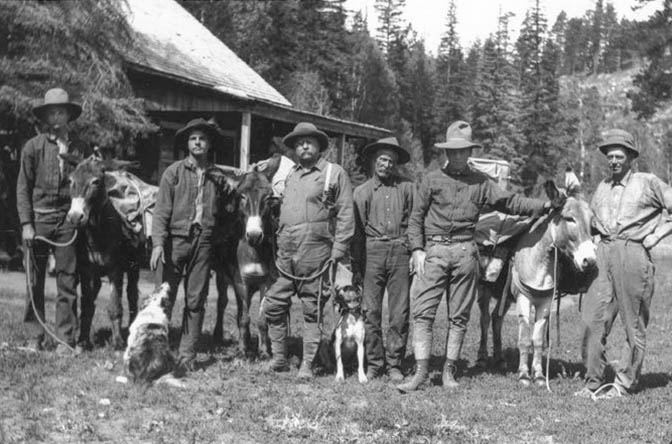

As far back as the late 19th Century, only a handful of ranchers and cowboys, and maybe a few sheepherders had come across the arch. None of them were impressed; tourism as a profitable industry had only occurred to a few enterprising Americans. Even the uniqueness of this sandstone span failed to attract many visitors. In 1898, John Wesley Wolfe moved West from Ohio for health reasons. His doctor thought the desert air might extend his life. He and his son Fred found their way to Southeast Utah, to the Salt Wash area below the arch and established a ranch there. He built a primitive cabin and eked out a living. When his daughter Flora Stanley and her husband Ed visited him in 1907, she was appalled at the living conditions and made him build a new cabin. At some point he mentioned the arch to his daughter who made the two mile trek and is credited with the first known photo of what was then called “The School Marm’s Bloomers.” According to early Park Service reports, the arch sported a variety of nicknames, from “Pants Crotch,” to “Mary’s Bloomers,” to the less colorful “Salt Wash Arch.” It most likely depended on which name the various ranchers preferred.

About 1908, John Wesley Wolfe, was persuaded by his daughter to move to Moab. He and the family soon returned to Ohio and eventually sold “Wolfe Ranch” to a local named Tommy Larson, who in turn sold it again. Marv Turnbow had come north from Texas, in search of new grazing lands. He managed the ranch for almost twenty years and the cabin became known locally as “Turnbow Cabin.” That name appeared regularly on USGS topographic maps well into the 1970s.

When Wolfe’s granddaughter, Esther Rison, returned to Arches in 1971, her visit and the detailed information she provided to park officials about the early history of the ranch, persuaded them to push for a re-designation of the site. “Turnbow Cabin” was lost to history and Wolfe’s name was officially restored. Still, for 30 years, until the Turnbow family sold the ranch to yet another local cattleman, Emmit Elizondo, Marv Turnbow played a major role in the monument’s early years, after President Hoover proclaimed the new Arches National Monument in 1929. But the monument was tiny by today’s standards. Hoover chose the “smallest size possible,” as defined in the Antiquities Act, and selected two separate parcels of land –– one in the Devils Garden and another in an area even then called “The Windows.” Ironically, the “Bloomers” wasn’t even included in the original proclamation.

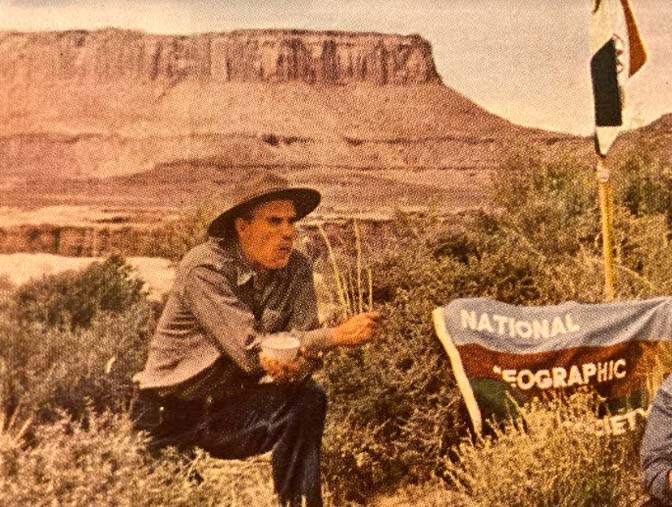

But in December 1933, the Arches National Monument Scientific Expedition came to Utah, a project funded by one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, the Civilian Works Administration Project. Its director, Frank Beckwith, was tasked with documenting the monument’s “natural and archaeological resources.” Beckwith discovered that there were far more geological wonders than what was included in the original 4000 acre designation. He is also credited with renaming the “Bloomers” with the more dignified “Delicate Arch” in his 1934 report to the Interior Secretary. And again, he noted that “the delicate arch” wasn’t even included withinin the original monument boundary.

In 1938, with the encouragement of Moab citizens like Dr. J.W “Doc” Williams and the local newspaper publisher “Bish” Taylor, President Roosevet dramatically expanded the size of the Monument to more than 33,000 acres. Finally, Delicate Arch fell under the official jurisdiction of the National Park Service.

Because Marv Turnbow was one of the few locals who actually spent large periods of time in the arches country, albeit as a rancher, he became the first official “custodian” of Arches National Monument. His appointment was probably also a result of his essential contribution guiding the Beckwith Expedition. It was Marv, in fact, who led Beckwith and company to the Bloomers.

Beckwith was slightly annoyed by Turnbow’s lack of enthusiasm for the unworldly landscape and was reported to say later that he “didn’t realize there was anything special about the area.” But for the early settlers like Marv, who were trying to make a living on cattle that resided mostly on hard rock and sand, his lack of enthusiasm is understandable. Cows like to eat grass, not Entrada sandstone. In those days, conservation was rarely practiced and by the time Esther Rison returned to the park in 1971, the landscape bore little resemblance to the lush grasses that grew there 70 years earlier. Turnbow remained custodian until 1939, when he was killed in a tragic car accident near Moab, just past the Mill Creek bridge..

(For much more about Marv, read the Zephyr’s first Blue Moon Extra about his stepdaughter, Toots McDougald…and look for another Zephyr story about Marv Turnbow, coming soon)

Turnbow was briefly replaced by local photographer Harry Reed . But later in 1939, Henry “Hank” Schmidt, a Park Service employee, took over the custodian duties and remained until 1942. Lewis T. “Mac” McKinney followed Hank but only stayed a year. In 1943, Russ Mahan, an NPS ranger came to Arches and it was Mahan who first expressed concerns about the future of Delicate Arch. Though a relative handful of tourists made their way to the arch via the old circuitous route, Mahan felt the arch was called “delicate” with good reason. He felt its demise might be imminent and he suggested for the first time that the Park Service should take steps to “stabilize” it.

GLUING DELICATE ARCH

I first became aware of this project when I read Edward Abbey’s “Desert Solitaire” in the late 60s. Abbey wrote:

“….there have been some, even in the Park Service, who advocate spraying Delicate Arch with a fixative of some sort — Elmer’s Glue perhaps or Lady Clairol Spray-Net.”

When I first read that passage, I assumed it was just another Cactus Ed embellishment. I had learned, over the years, to take some of his “facts” with a grain of salt. The idea of spraying Delicate Arch with a fixative was too ridiculous to be taken seriously. This, of course, was before my decade of employment with the federal government.

During my first winter at Arches, when the tourists were few and far between, I spent much of my day rummaging through file cabinets, reading old monthly reports, and looking at the black & white photo collection. One day, a labeled folder caught my eye. It read: “Delicate Arch Stabilization Project.” I remembered the remark in Desert Solitaire but still couldn’t quite believe my eyes.

What I found inside was a decade’s worth of memorandums, letters, and reports, all dedicated to the question – should the Park Service save Delicate Arch from imminent collapse?

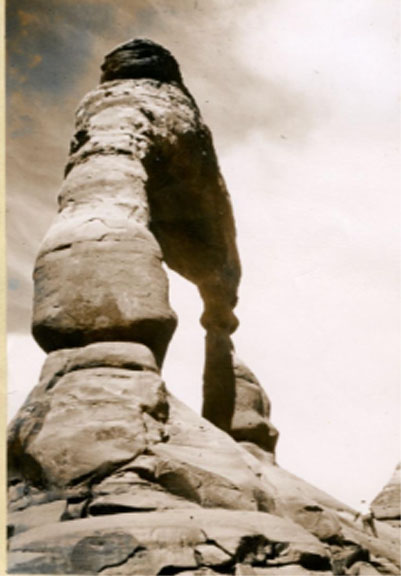

The issue was first raised by Arches Custodian Russ Mahan on August 28, 1947 in a memo to the Regional Director. On a recent hike, Russ had observed “the eroded condition of the east leg of Delicate Arch … It is my opinion that some measures should be taken to prevent further erosion and to stabilize this particular point. If we lost this arch we would be losing one of the most important features of Arches National Monument.”

Mahan was convinced apparently that the collapse of Delicate Arch might very well take away any incentive to visit the park at all.

In any case, the letter got the ball rolling, but just barely. The acting Regional director sent Mahan’s concerns to the Director in Washington. “There was,” he added, “the possibility that (the) condition of the formation may endanger visitors there.” But the threat of an arch squashing innocent tourists was not enough to elicit much interest. The next memorandum, dated September 13, 1951 said only that, “with specific data, previously lacking, the matter can be discussed again to determine what action, if any, this office is willing to recommend.”

Obviously, there was not a great deal of enthusiasm for this project. But 18 months later, interest was re-kindled when Southwest Regional Assistant Director Hugh Miller visited the arch and threw his support behind the plan:

“I have decided to join, as a result of this trip, those who believe that stabilization of Delicate Arch is warranted. I would favor the proposal only with the understanding that a very simple plaster jacket could be placed over the weak point in the arch at which erosion threatens to topple it, sufficient only to arrest further erosion at that point. Careful staining would suffice to make such minor support unobjectionable in appearance and it seems to me that it might reasonably be effective. From my own point of view, the Delicate Arch is so outstandingly unique a formation as to merit the adoption of stabilization methods.”

The general superintendent in Globe Arizona was delighted. “It is encouraging indeed,” he said, “to know that Mr. Miller is in accord with our view.” Although the NPS Advisory Board opposed the stabilization of geological formations in National parks, Davis insisted that Delicate Arch should be an exception. On December 22, 1952 he wrote:

“I believe we are all agreed that one use of our Parks and Monuments is as great outdoor museums and, as such, Arches National Monument has perhaps its most effective exhibit in Delicate Arch. To allow this unique formation to fall without making some effort to prolong its existence would be to lose forever an integral part of the story justifying the existence of Arches National Monument.”

Within months, memorandums no longer asked if the arch should be stabilized but “where and what method should be used.” By the spring of 1954, the memorandums were flying at a fever pitch. A meeting was proposed for March 3, 1954 and was to include representatives from the Engineering Division and the Landscape Architectural Division. They were to “discuss the stabilization of Delicate Arch and to make arrangements for the execution of the proposed work.”

And then came landscape architect David Van Pelt. Obviously not caught up in the stabilization fever that had affected others, Van Pelt met with Superintendent Bates Wilson at Arches, discussed the question of stabilization and filed his report. He was the first to see that meddling with Mother Nature might very well backfire. “It should be realized,” he wrote, “that the wisdom and success of whatever action may or may not be taken to stabilize the arch can never be accurately appraised.”

Van Pelt proposed two alternatives:

1. To take no measures toward stabilization. This view arises not out of indifference nor apathy, but from a consideration of the uncertain benefits of stabilization, of the very real possibility that more harm than benefit may be done, and in the knowledge that Delicate Arch is “in extremis”, its collapse only deferred by the efforts of man.

The stabilization of ruins does not offer a precedent in the analysis of the weaknesses of the arch, nor in procedures for strengthening it. The collapse of ruins follows definite patterns according to their methods of construction, such methods being few in number and not fully understood. They are restored by proven techniques, based on known forces, strength of materials, etc.

A complete stabilization, using methods common to ruins stabilization, of Delicate Arch would involve uncertain results, not inconsiderable danger to arch and workmen, and great expense. The arch is in a relatively inaccessible location, to which all materials and equipment would have to be hauled by pack-animal or small tractor. It is poised on the edge of a deep canyon, necessitating extra safety precautions. No one can say that it would not partially or wholly collapse while work was in progress.

2. The contention that nothing should be done is prey to the equally defensible argument that, since the patient is doomed anyway, we are justified in making some attempt to prolong his life.

If the project was to proceed, the most efficient technique seemed to call for the spraying of the weak leg with a silicone epoxy. Another option, proposed by engineer J.R. Lasstic, was “to ring the weak point of the weaker leg with a concrete collar, making an attempt to color and form the concrete to blend as well as possible with the natural structure.”

Superintendent Davis in Globe, Arizona bubbled with enthusiasm. Despite Van Pelt’s warnings, Davis felt that “the trial use of a silicone preparation can certainly do no damage and it may well afford some protection from weathering.” The Regional office seemed to be in contact with every silicone manufacturer in the country requesting free samples. And Davis added, “I suggest that all of these be field tested at Arches.”

Meanwhile, the staff at Arches appeared to be hiding as best it could from the entire project. Arches superintendent Bates Wilson’s signature is conspicuously absent from all correspondence. General Superintendent Davis, concerned that the silicone had not been tested, inquired as to whether they needed more. A few weeks later, Davis sent another memo to Bates Wilson, asking him to estimate needed additional funds to complete the job. No reply from Arches. On October 13, 1954 the acting General Superintendent sent Bates one more memo. “Will you please,” he pleaded, “make a special report on this project at your very earliest convenience?”

Acting Arches Superintendent Bob Morris finally responded. “Well, it seems they mixed the ethyl silicate solution back in February and it was supposed to be applied within 90 days. Now, with winter closing in,” Morris asked Davis, “To get the proper results, should we not order a new mixture?”

A tense memo came back from Davis. Write the manufacturer, he suggested, if they thought the silicone had gone bad. “A tabulation of the dates of treatment and a complete record of your observations should be made and forwarded to this office.”

Arches appeared to have worn the general superintendent down. The memos petered out and the issue died for almost two years. Then in 1956, Mr. Cutler, a visitor to Arches, sent a letter to the NPS Director, concerned with preserving Delicate Arch “for millions yet unborn.” Incredibly, he suggested “that a clear, erosion-resistant material could be sprayed on.”

The Acting Regional Director, Harthon Bill replied to the letter and advised the concerned citizen of the March 1954 study. “This office,” Mr. Bill advised, “is not currently aware of the immediate status of the work at stabilizing Delicate Arch. We can, however, assure you that this is an active project and every effort is being made to slow down natural processes of weathering with the objective of lengthening the life of this natural feature to the greatest possible extent.”

Finally, on April 27, 1956, Mr. Cutler received another letter from the Park Service Regional office. “During a recent visit to this office,” the letter stated, “Superintendent Wilson stated that several of the chemicals had proven unsatisfactory, because exposure to the weather had caused them to turn white, or scale off, or both.” Wilson also felt that it would require “several more years of experimentation” before the process could be implemented on the arch.

With that, the idea finally collapsed. Bates Wilson, it appeared, simply outlasted the Regional bureaucrats. No one loved Delicate Arch more than Bates, but the idea of sealing silicone on it with an orchard sprayer never appealed to his common sense. He continued to worry about Delicate Arch, but not from the standpoint of its collapse.

NO GLUE…BUT WHAT ABOUT DYNAMITE? THE NEW TRAIL

Bates Wilson followed Mahan as custodian but was soon designated Arches’ first official superintendent. Bates was also the first NPS employee at Arches (other than Harry Reed whose real profession was a landscape photographer), to make a real effort to connect with the various organizations in Moab that had an interest in tourism and promoting the monument.

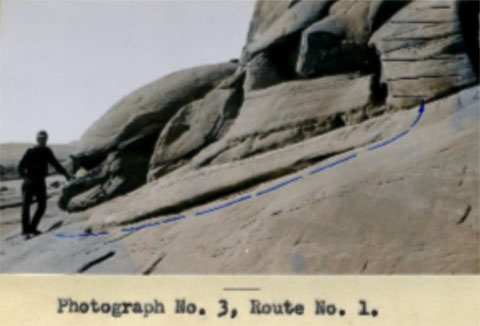

In 1952, at a national monument that could often count its monthly visitation in the hundreds, Arches officials and local tourism boosters were anxious to boost its numbers. Delicate Arch was already earning a reputation for its singular beauty. Ironically the first cover photograph of Delicate Arch appeared in the U.S. Vanadium Company Magazine, a publication devoted to uranium mining.

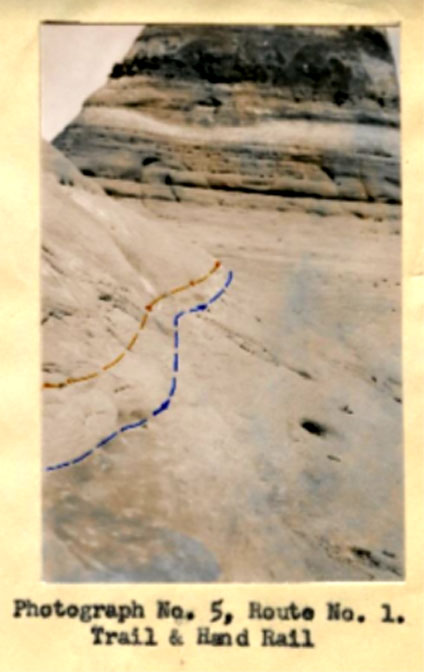

Access to the arch was a serious and valid concern. The trailhead began near today’s Delicate Arch Viewpoint. Hikers descended a trail into Winter Camp Wash and then by the most difficult and sometimes hazardous climb up an adjacent sandstone fin, reached the backside of Delicate Arch. Bates and other NPS officials believed they needed a new trail. But it would not be easy. Planning began in 1952 and as always, the decisions were made by committee. Not only were Arches staff involved, personnel from the regional office often had the final word. Finally in December 1952, construction began, The plan was to cut a horizontal trail from the side of a sandstone fin, across from the natural sandstone bowl in front of Delicate Arch. Now the trail’s approach would come from the north and hikers would not see the arch until the very last moment. It was by any measure, a very dramatic moment when hikers walked those last few steps.

(A slide show with narration about the hike to Delicate Arch was played at the old Arches visitor center auditorium for years. We who worked the desk almost went mad after several hundred showings. Most of us had memorized the entire narration– I will always recall the last line: “What I saw around that final bend, I shall never forget…a magnificent arch, framed by sky and snow capped mountains.”)

According to Bates’ December 1952 report, workers tried to use a “Parco Drill” to place holes in the sandstone to load the dynamite. But the drill wouldn’t bore holes deep enough to do the job. The NPS contacted another company Schramm Tractors, who had the equipment to get the job done. In February, another staffer from region, Carl Alleman, revised the final approach and construction was restarted. Then it was paused yet again. But by the end of April, Wilson reported that “two-thirds of the work” was complete and that progress was being made far faster than expected. Bates wrote, “The new trail was made passable during the first week of May and inspected by Landscape Architect David Van Pelt.. he suggested widening the trail in a few places. Work was held up by complications in purchasing dynamite and caps, but was today resumed…it is hoped that the blasting job will be completed very soon.”

And finally, Bates reported that, “the new portion of the Delicate Arch Trail sas completed on May 27….We have gotten many favorable compliments on the new and safe approach, especially from older people who had attempted the hike before and were unable to reach their destination.”

National publicity was almost immediate. Bates noted that:

“Life Magazine’s new issue featured a beautiful cover picture by Joseph Muench, of the Delicate Arch. We understand that this is the first time that an attraction in our area has appeared on the cover of a magazine with such widespread circulation that Life has… “This front cover splash seems to have set off an Atomic Chain reaction, for in the past week a number of calls have been received from other national publications requesting detailed information on Delicate Arch.”

Within a year, Bates would write in his monthly report, “the increasing desire of fools to carve their names in public places has reached the highest level possible in Arches at Delicate Arch.”

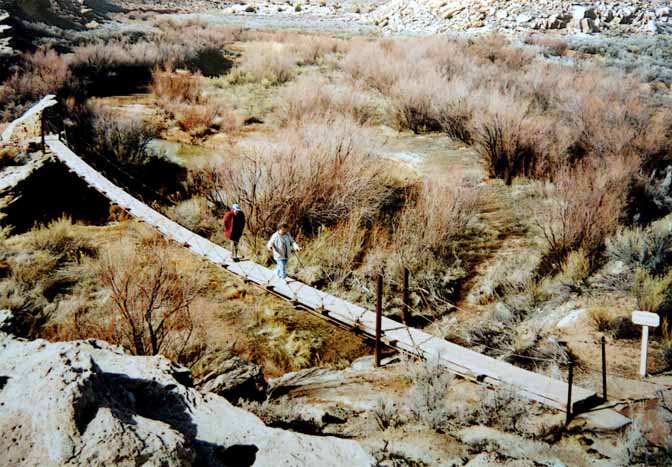

It had begun. Within years, the park was seeing increased vandalism at the arch, and elsewhere. And somehow tourists kept getting lost on the new trail. On that first long incline after the Salt Wash bridge, tourists seemed to miss the rock cairns that marked the way, and even the painted arrows that Bates reluctantly added. Finally, on stretches of sandstone where the greatest number of lost hikers seemed to occur, the park’s maintenance crew actually poured an asphalt trail OVER the sandstone. Almost from the outset, the asphalt covering struck most people as a bad idea— Ed Abbey would later refer to it as the “Portland Formation.” Slowly, over the years and when time allowed, the NPS began chiseling up the black pavement. But even in the 1980s, there were still sections of “the Portland Formation” to puzzle both tourists and future NPS staff.

Whether there are any historic asphalt remnants remaining, I couldn’t say.

FORTY YEARS LATER—PAVING THE ROAD

As the final touches were being made to the new trail, construction was also underway on a new paved entrance road. Mission 66, a massive public works program to improve the roads and infrastructure of national parks across the country, included millions for Arches. The old Willow Springs entrance road was abandoned, and a new modern highway was planned, starting at the site of the visitor center. In fact, work on the switchbacks above park headquarters had started in 1940 by the old CCC crews. But World War II put a fast stop to that project and the unfinished road remained like that for another decade after the war’s end.

But in 1957, even as Ranger Abbey was allegedly pulling survey stakes, the federal highway department was moving at full speed to construct the first phase. By the summer of 1958, the new road that now passed through the Courthouse Towers and climbed the long grade to Balanced Rock was complete. Soon after, the Windows road was finished as well. It took until 1963 to complete the last nine miles of paved highway to the Devils Garden. The new campground with its paved “designated sites” and “comfort stations” opened for business as well.

And yet….for reasons I was grateful for but never understood, a decision was made by the NPS to leave the Delicate Arch road unpaved, and not just to the trailhead. The dirt and gravel road continued past the trailhead and Wolfe Ranch for another couple miles, all the way to the Viewpoint. The sight of a gravel road stopped a lot of tourists from going further. A turnaround at the main road junction was even added to give the dissenting trailer owners some room to turn around.

(On a busy summer day) by Jim Stiles

Late 1970s. By Jim Stiles

In addition to the road conditions, vehicles had to cross three washes. Being a desert with an annual rainfall of less than ten inches, the wash crossings were usually bone dry. But when it rained, it could really rip. Perhaps three or four times a year, visitors found themselves caught on the wrong side of at least one of those washes. Salt Valley Wash, which drained all of Salt Valley and the high ridges on each side was often the most difficult to predict.

In the late 70s and early 80s, I was the “in park” ranger and it was my job to warn visitors of the flash flood threat, and to assist them when the warning came too late. As noted, Salt Valley Wash originates to the west and north of Delicate Arch and drains a large portion of the Devils Garden, and the Fiery Furnace. In the desert, “isolated thunderstorms” really live up to their name. While it’s sunny and calm at Wolfe Ranch, it can be raining torrents a couple miles upstream.

As I raced down from the campground, I’d sometimes be able to see the flood building in every rivulet and side drainage, but would be hard-pressed to convince anyone at the trailhead that a wall of water was on the way. After doing my best to spread the word, I’d drive back across the wash to the safe side and wait.

Photo by Jim Stiles

I could usually hear the oncoming flood before I saw it. The head of a flash flood doesn’t roar, it hisses. Before the water comes the foam, a thick brown foam that inches down the waterway at a pace that always seems so much slower than the wall of water that’s directly behind it. I’ve walked out into the middle of a dry wash and waited for the foam. And when it arrived, managed to stay just inches ahead of it while walking at a leisurely pace. It always felt like I was being followed by the Blob.

When the non-believers finally decided to make their departure, and drove 200 yards to the Salt Valley Wash crossing, I always liked to be there to say something a bit kinder than,“Neener, neener.” But while the flood sometimes meant they missed their dinner reservations, or threw them off their itinerary, I never saw anything but smiles and sheer wonder on the faces of the stranded tourists. How many people can say they were stranded on a dirt road in the desert by a flash flood that arrived while the sun was shining? Some of the best “campfire talks” ever given at Arches were shouted across Salt Valley Wash to an amazed, albeit captive audience?

It usually took a couple of hours for the water to subside and another hour for the wash bottom to become firm enough to support the weight of a vehicle.

Then, in 1983, the NPS Road crew spent a day doing bulldozer practice in the wash and actually altered its gradient. When they were done, water had to flow uphill at the wash crossing. And when the next flash flood came along, the water pooled, instead of flowing downstream, and the crossing became a quagmire every time it flooded. More roadwork by the crew only made matters worse. At one point in the late 1980s, the entire Delicate Arch road was closed for over a month.

*****

Pete Parry, the Arches/Canyonlands superintendent from the mid-70s to the late 80s, resisted the idea of paving the road. He also kept pro-pavers of the Island in the Sky road at bay while he strove to find a less intrusive option. Pete had high hopes for a material called “soil cement,” which he believed might allow a safe and relatively smooth experience, without resorting to wide asphalt highways and the endless paved pullouts. The Delicate Arch road, from the main highway to Wolfe ranch, was Pete’s test project. But ultimately the heavy use by motorhomes and trailers caused the soil to break up. It was a failure.

Pete retired soon after and by 1993, the Delicate Arch road was paved, striped and even curbed in places, as was the parking lot. Low bridges were built for the three wash crossings, and the old swing foot bridge was replaced by a steel girder walking bridge at a cost of a few hundred thousand dollars. The road to the viewpoint was also paved and a massive asphalt parking lot was built there as well to accommodate all the tour buses and monster RVs. Over the years, as visitation exploded the lots were expanded.

While I guess the “improvements” made were inevitable, visitors who came after 1993 never knew what they had missed. In those days of long ago, ordinary, uneventful vacations became extraordinary, memorable adventures for people whose lives were already often confined to dreadful routines. Getting stranded in a flash flood became THE story they told first when they got home to share their vacation memories. And it was nice to know that Nature could still have her way once in a while, and force us to live by her schedule.

Paving of the Delicate Arch road guaranteed a safe, smooth, on-schedule visit. But it lost something in the process.

AND FINALLY…THE MOB COMETH”

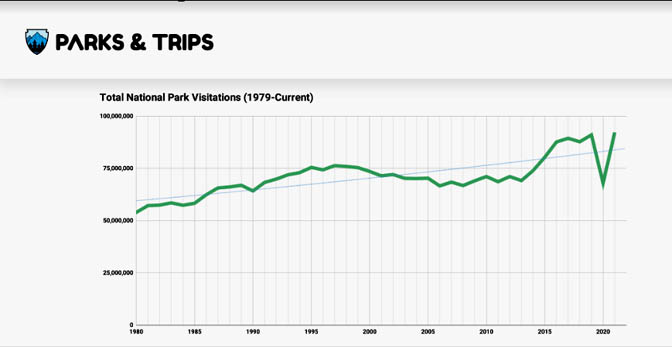

The Park Service and, of course the Industrial Tourist/Recreation industry has always been concerned with numbers. Few park superintendents ever thought their tenure had been a success if visitation to his/her park failed to grow dramatically.

There was even a time in the early part of this century where officials and tourist entrepreneurs were concerned that park visitation was declining. And in fact, at many NPS units, the numbers of tourists had declined or at the very least, the rate of growth had slowed.

In the early 2000s, an organization called the Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Units” or CESUs met to discuss the future. CESU described itself as:

“…a network of cooperative research units (that) has been established to provide research, technical assistance, and education to resource and environmental managers…multiple Federal agencies and universities are among the partners in this program. Ecosystem studies involve the biological, physical, social, and cultural sciences needed to address resource issues and interdisciplinary problem solving at multiple scales and in an ecosystem context. Resources encompass natural and cultural resources.”

At a joint meeting of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains CESUs in April 2006, the topic was “Tourism Break-Out.” Here are some excerpts:

“Regarding tourism and tourism patterns in the West, the key issue is CHANGE – including changes in visitor groups, desired activities, desired experiences, tourism patterns – and how these changes will influence federal land managers – in the short and long term.”

This section particularly moved me:

“A recurring discussion theme was that it’s important to have young people involved in projects – because they are a primary age group that we need to know more about, and a group that can help federal agencies recognize future needs. CESU collaboration with universities provides an excellent way to reach this group of young researchers/project team members.

“It is critical for federal managers to understand how different groups want to use federal lands and, in the same way, how they value federal lands. For example, how do BLM and/or NPS lands ‘resonate’ with different age groups or ethnic groups – and what will this mean for the long-term support and interest in their federal lands.”

Among the topics associated with this were:

“The changing values of generations regarding parks – what one generation values in a park (such as solitude) may be less important to another generation (that may be more interested in extreme sports). -emphasis added-

“Use of Ipods, GIS, computer technology and how that can assist in site interpretation. Issue of “Receptivity.”)

“Great potential for partnerships with outdoor recreation outfitters, suppliers, clothing manufacturers, etc., who already know a great deal about our federal land visitors and have a strong handle on how people are using that land.”

In effect, they were asking, what could land management agencies do, working cooperatively with the recreation industry, to maintain and expand the visitation and use of federal lands? And how could they… and is there another word?...pander to younger generations who were no longer moved by the sheer beauty of the national parks and other scenic federal lands? We know what happened, though even these folks couldn’t see the monster they were helping to create. In the coming decades, social media, in all its incarnations, transformed our parks and other scenic places that were once quiet refuges from the mad, mad world we were all trying to escape.

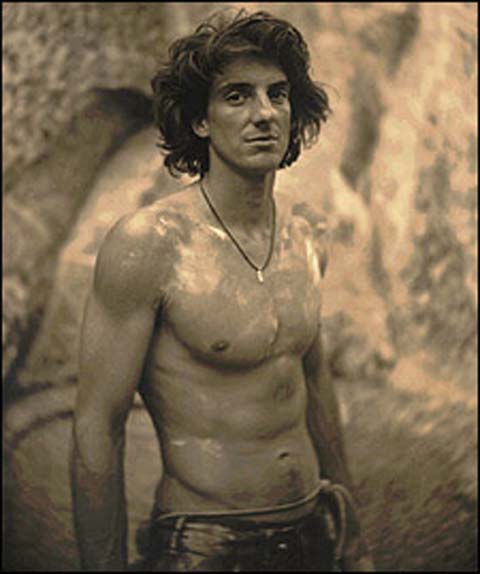

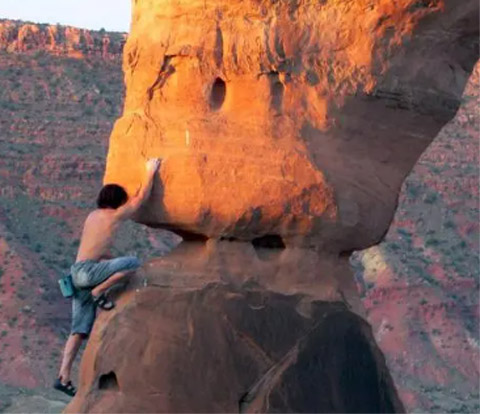

Note that “smart phones” were still half a decade in the future, but the CESU report actually referenced “extreme sports” as an activity that might stimulate more interest in the parks from younger Americans. Not long after the CESU report was released, print and electronic media in Salt Lake City, Utah enthusiastically reported the first free ascent of Delicate Arch. Professional climber, Dean Potter, brought a High Definition video camera and two other photographers to capture this historic moment. Potter established photo points and staged his climb again and again, just to be sure he got all the camera angles he needed.

Salt Lake media received news of the climb from the Patagonia outdoor clothing store in Salt Lake City, and advised them that HighDef video of the dramatic first ascent was available. She also provided the climber’s contact information for interviews. And the media, always looking for good “visuals,” came running. The climb was featured on Salt Lake television stations and made page one of the Salt Lake Tribune. NPR interviewed Potter live on “All Things Considered;” the interviewer sounded awestruck. But the climb should also have been illegal. In fact, it was illegal for decades, but when the NPS took the teeth out of its own climbing regulations in 1988, this kind of stunt was bound to occur.

In 2003, then-NPS SE Group Superintendent Jerry Banta called the Arches climbing policy the “weakest” he had ever seen. But nothing happened and Potter and his team read the regs closer than the rangers—the wording only said that named arches “may be closed” by the superintendent. So a bureaucratic misstep allowed the climb to occur.

Reaction to the ascent was mixed. FOX13 News interviewed a sales person at a Moab climbing shop who had nothing but praise for the man and his achievement and suggested, “He deserves our respect.” However, Arches Superintendent Laura Joss was not impressed and told the Tribune, “I’m very sorry to see someone do this to Utah’s most visible icon.” The next day she strengthened Arches’ climbing policy and banned climbing on all named arches. No “may be” this time.

In Potter’s FOX13 segment, he talked about “cherishing the moment” and being “close to Nature,” and that he viewed the arch “with great reverence.” Potter was known among his peers as a world class climber. He is best remembered for scaling a particularly difficult route on El Capitan in Yosemite and was chronicled in an OUTSIDE magazine story. He did it in record time—3 hours and 24 minutes. However, his historic feat didn’t leave much time for spiritual connections or cherishing the moments.

Potter was also a paid “climbing ambassador” for the outdoor clothing company Patagonia, who, we now know, leaked their representative’s feat in the first place. However, as his climb drew more unwanted publicity, especially from the Park Service, Patagonia distanced itself from Potter’s dubious accomplishment, and eventually fired him. Potter later died at Yosemite in a “wingsuit” free flight event; he miscalculated the distance between two rock spires and struck one of them at 130 mph. He was killed instantly.

EPILOGUE

As the recreation industry embraced the extraordinary profits to be squeezed from the exploitation of Nature, even environmental organizations across the country started re-thinking their wilderness strategy. “The Wilderness Mentoring Conference of 1998″ was a gathering of self-proclaimed “mentors,” professional environmentalists — New Environmentalists — who were frustrated by the movement’s lack of progress in pushing and passing wilderness legislation across the country.

Its participants came from national and regional environmental organizations coast-to-coast, and included representatives of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA), including its then-Executive Director, Mike Matz.Matz who presided over the conference as mentor-in-chief.

While the organizers of the event paid tribute to the wilderness activists who had come before, clearly the purpose of the meeting was to propose a new approach.

“Although it is important to pioneer new wilderness strategies,” the report explained almost as an afterthought, “we must do so with knowledge of what has come before.” With that token nod to the “importance of history” and to the “philosophical and political contexts” of the wilderness movement, the conference explored the new territories of salesmanship, marketing and media manipulation to win the legislative wilderness battle.

A prominently displayed quote by Michael Carroll, later of The Wilderness Society, established the tone and direction of all that would come later:

“Car companies and makers of sports drinks use wilderness to sell their products. We have to market wilderness as a product people want to have.”

These were all quotes from the report:

“Gimmicks…Catchy slogans…ask a rancher to support you…get Joe movie star as a spokesman…Cleverly quote John Muir…Ask experts to endorse your ‘product.’…Show people having fun in the wilderness.”

It all came to pass.

Today, and for the last decade, we know what has happened to Arches National Park, and other scenic wonders in America. Last year the NPS created a reservation only test program for Arches. To enter the park during peak periods, would-be visitors needed to apply months in advance for a special permit. Before that drastic measure was taken, the Arches entrance station staff was known to deal with lines of vehicles that at times stretched several miles, extending all the way to the shoulders of US 191. The parking lots during the season are still almost always at capacity or beyond it. Traffic resembles a busy two lane surface street in Los Angeles.

And Delicate Arch? The most “iconic” natural arch on the planet? The crowds during the season start early and last all day. In fact, sunset AND sunrise are often busier than any other time of day. Everyone wants their picture standing in front of the School Marm’s Bloomers, to post on Instagram. Photographs of the crowds regularly make their way to social media. As I noted earlier, the mob looks more like a concert venue or maybe a boxing match, than a place to pursue beauty in the midst of solitude.

****

What does the future of public lands, and society itself, hold for us? And what do those who hope to shape the future want from it? As energy costs rise and the population swells, what kind of tourism will survive? Many believe it will flourish and grow, but their vision guarantees it will be very different. Mass transit systems, shuttles–now touted as the ultimate “solution”— and a group ethic will prevail. I keep hearing the word, “collective,” even among environmentalists who can embrace the end of the individual and then revere Ed Abbey in the next breath. Go figure.

A certain amount of regimentation will be inevitable for mass transit and regional shuttles to operate on such a vast scale. In this future, opportunities for solitude will survive, but not as some of us still define the word. It’s painful to ponder, but as inevitable as sunrise.

What’s notable is that for many travelers to Moab in 2023, the Future is already here. And for them, it doesn’t sound that bad. The world keeps turning over, again and again, faster than any of us dreamed possible. As technology continues to shrink the world, its newer citizens embrace the collective over the solitary. To younger generations, solitude feels more like isolation in 2023 and it has no place in the Brave New West. We all cherish the shared experience, but there was always a need for the empty room. Now the need recedes. “Rugged Individualism” has been in decline for decades. Now it appears to be in its death throes.

Last year, environmental journalist Jonathan Thompson penned an essay about his recent experiences as a tour guide. Among the destinations was Zion National Park. The park was SRO — “standing room only.” But Thompson wasn’t particularly troubled. He wrote, in part:

“And yet, I was also giddy about my surroundings, and found myself gawking, awestruck, at the dramatic landscape.. That I was sharing that beauty with some 17,000 other people that day did not, in itself, diminish the beauty in any way…. with apologies for anthropomorphizing, I kind of doubt that the Place really gives a damn whether all those people are looking at it or not. The masses have an impact, of course, but to imply that they somehow suck the soul out of the place, to think that it is any less sublime because of the numbers of people, is to underestimate the power and strength of Beauty and of Place.”

No…I disagree. it does matter. Those 17,000 “gawking tourists” do affect the trees and the rocks (or “The place” as Thompson called it) . He says the rocks are indifferent to us. If that’s true, then I doubt they’d object to a drill rig or a few cows either. But if they were sentient beings, with the ability to offer an opinion, I’m sure they’d be more than eager to express one. And my guess is, they’d tell us just how badly their souls are being crushed. To ignore the fact that the rocks and trees can’t “speak” for themselves doesn’t make the degradation of their environment any less appalling, by whatever means they’re being subjected to. To suggest otherwise is to ignore our own souls and consciences. Whether the rocks are more appalled by 17,000 tourists in cargo shorts, tank tops, and flip flops, or a few cud chewing cows, well…. I wish I could ask them.

And so, we offer a lament, as the love and longing for the quiet moment, passes into history. From generation to generation, priorities change. In a century, how will humans remember Thoreau, or Muir, or Leopold, or Abbey? Even now, we are seeing revisionists taking aim at them.

It is comforting to know that solitude is out there, if you know where to look for it, but who’s looking? And who would notice or care if it went away?

Is that a bad thing? Who knows? Maybe not. But Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, “Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.” The world has lost patience with Nature these days. They’ll never know what they threw away.

As for Delicate Arch, it survives without the Elmer’s Glue and it doesn’t look much different than that photograph Flora Stanley shot over 100 years ago. But we all know, in our heart of hearts, that it’s nothing like it once was. I might have liked it more when the best thing you could say about the canyon country was the wisdom of the unknown rancher, over a century ago, who is alleged to have complained: “It’s a hell of a place to lose a cow.”

Amen

from “Turnbow Cabin.” (photo credit: James Stiles, Sr.)

A Vision of the Future by Hayley Knouff

JIM STILES is the founding publisher & editor of The Zephyr (“Clinging Hopelessly to the Past since 1989”) cczephyr@gmail.com

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE…THANKS—JS

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our amazing historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/01/01/unsung-videographers-of-canyon-country-1949-ray-virginia-garner-zx43/

By Harvey Leake (ZX#35)

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/11/13/encounters-with-the-sublime-quentin-roosevelts-western-adventures-by-harvey-leake-zx35/

DENNISE SULLIVAN..by Jim Stiles (ZX#8) https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

The naming of Delicate Arch has one, possibly apocryphal, version that claims its original name was “Landscape Arch” and the Landscape Arch we know–which is the most delicate of all–was “Delicate Arch.” Somehow their names were reversed in an early registry of the monument. Did you ever hear this story or see record of it when you were at the Park?

Waiting for the sunset amongst the Delicate Arch concert crowd 20 some years ago, I noted the light changing. This was the glowing redrock photograph that at least 100 people all wanted to take. A pair of visitors ambled out right under the arch at this very moment. The acoustics in the slickrock bowl are pretty lively. I stood up and said only a notch louder than out loud, ‘hey you! You’re gonna be in a hundred people’s sunset photographs’. The two persons, startled by this attention, moved about 6 feet to the left. “You’re still in the photo!” I hollered. The people picnicking to my right, chattering away in German, looked at me like I was the biggest asshole that ever lived. Who knows, maybe I am.

We must be related.

Your ’78 picture of Delicate Arch from Winter Camp Wash was absolutely wonderful! That’s the type of picture for National Geographic! But we oldsters all know our parks need no further advertising!

Just out of Las Vegas, the Red Rock area has had to institute a reservation system to keep the Park from being overcrowded. Still in their back areas they’ve dealt with vandalism! A small historical area near the Nelson, NV area, which oldtime residents tried to keep a secret, had a vandal throw a tire above pictographs, set it on fire and the rubber melted and ruined the art! A small outdoor outhouse was built for the convenience of visitors—who promptly tour it down and used the wood frame for campfires!! Years ago our motorcycle group had permission to throw up tents on the grass in Zion for a weekend. We cleaned the whole area prior to our visit and after, unlike visitors these days who throw beer and pop cans around wherever! Now one must take a shuttle into Zion.

I’m with you in believing that easy access had given those would be vandals just that!!!

This article is most interesting, the old pictures great.

RE: When you do not agree with the Experts/Managers:

Bates, my Dad, was not a good typist, hated office work, knew he could not win a battle of/with Memos so took one or two approaches to issues important to him and of the day:

1) Ignore the memos he got…and if things got “hot” someone would show up (i.e. @ Arches HQ.)..he would give them a Jim Beam, go camping and have a dutch oven dinner and “discuss” the matter.

2) Let them just show-up and on the GROUND he would:

a) out walk them,

b) get the assholes to see his point of view and

c) celebrate success with a Jim Beam and dutch oven meal at sunset and watch the dark sky from a cowboy bedroll.

Most of the time either # 1 or # 2 or 1 and 2 together worked.

Tug (Alan ) Wilson 1/16/23

Great story, Tug. Thanks.

Jim, my Young Adult Conservation Corps did soil cement on many sections of the trail to Delicate Arch in 1978. Walt Nunley I think might have been the crew leader or John Vicari. Damn we used to have fun at the Poplar Place after work.

I’d like to hear more about your project and whether the team thought the soil cement option would be successful. I was a ranger there in 1978…probably drove right past you guys. I can remember that the soil cement degraded in places but was never impassable. It was the wash crossing, or crossings, that stopped tourists completely. If I recall they built a low bridge at the Salt Valley Wash crossing, the one that kept visitors from reaching the trailhead. Didn’t IT wash out as well at one point?

Expert historical account of Delicate Arch. Thanks for keeping history alive. Very fine article

Was the rancher who lost the cow one of the Wetherill brothers?

Patching Delicate Arch reminded me of the attempts to preserve vehicle access over Elephant Hill in Needles by applying asphalt in loose sections. I haven’t been back there in ages so looked online for recent photos. Can’t see much of the road for the monstrous vehicles, and the volume of videos, including drones, made my innards uneasy, another little jolt under my sternum. It does matter, the soul can be sucked out of a place, it just may not be as apparent to those whose experience is only post sucking. It’s relative. Experiencing solace in solitude is no trifle thing.

I’ve been able to find somewhat remote solitude in parts of New England, and other not so sexy locations.

I’m currently working at Arches and I was wondering if you had any idea what happened to the folder with the stabilization project? I’d love to be able to see this for myself. I’m sure it’s been a very long time since you’ve been back, and I’m sure the folder was probably lost when they rebuilt the visitor center, but obviously you’d have a much better idea than I ever would. Thanks for your help.

-Gavin

Wow….that color photo of the rock climber at the weakest point in the Arch makes you realize what a VERY precarious little bit of rock is holding up the tons of sandstone above it! Nobody sneeze! (And please…not even a little earthquake!)