“A LITTLE HEAVEN ALL OUR OWN”

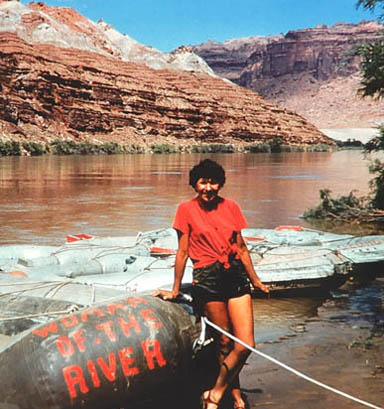

In the summer of 1957, the most remote “community” in the continental United States was remarkably busy— relatively speaking. The pioneering “Woman of the River,” Georgie White was running tourists from Green River, Utah. According to White, below its confluence, the Colorado River was running 110,000 cubic feet per second (cfs). Now, she and her party of 54 tourists, all happy to climb out of their rubber rafts and feel solid ground, paused here for a couple days to relax.

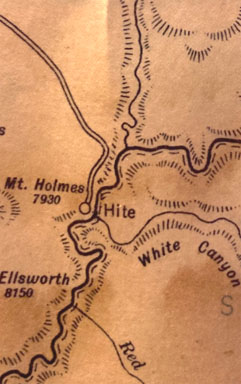

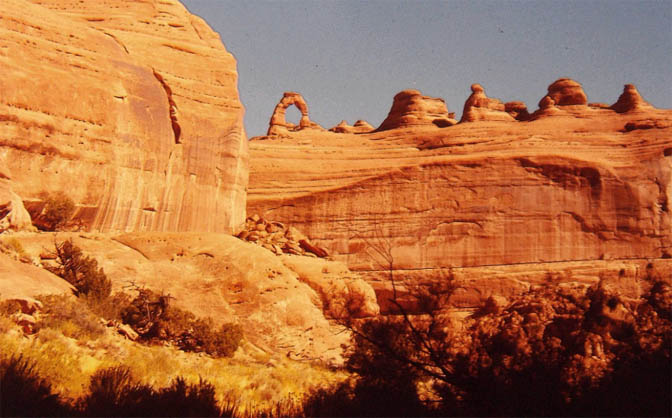

So did Kent and Fern Frost. Kent had become one of the most respected and sought after tour guides in a part of America that until the 1950s had been practically unknown. The southeast quadrant of the state of Utah was almost literally a blank spot on the map. Between the US 160 bridge at Moab, Utah and the US 89 Navajo Bridge at Marble Canyon, there wasn’t a single vehicular crossing of the Colorado River, a distance of more than 300 miles.

But after the end of the World War, and a decade long economic “Great Depression,” Americans were ready to see the country. Desert Magazine was created in 1946, and Kent Frost thought the magazine looked like a good forum to advertise his services. Canyonlands Tours became one of the best known tour companies in Southeast Utah. His orange Carry-Alls were easy to spot. Kent Frost’s reputation as the man who knew the canyon country like the back of his hand became legendary. This trip, Fern and Kent had decided to take some time off alone for a change. But they were still out there enjoying the scenery. There was nothing they loved more. The Frosts were headed for the Land of Standing Rocks and the Maze, some of the most rugged uncharted land in North America.

Now, and for more than a decade, there was another way to cross Colorado. In On September 17, 1946, Utah Governor of Herbert Maw, other public officials, and more than four hundred citizens gathered at a place known for decades as Dandy Crossing, or Hite Crossing, to celebrate the premier run of Arth Chaffin’s “Hite Ferry.” Legendary river runner Harry Aleson honored Chaffin at the dedication ceremony, noting:

“For years Arthur Chaffin’s ranch was unquestionably the most isolated in the United States. He lived 120 miles from the nearest railroad and his nearest neighbor downstream on the Colorado was at Lee’s Ferry, 162 miles distant. The next neighbor on the river was the Bright Angel Trail, 251 miles away in the bottom of the Grand Canyon. His third nearest neighbor was my father’s son, who lived at MY HOME, Arizona, 442 miles away in the bottom of the mile-deep Grand Canyon.

“Arthur Chaffin’s ranch is still isolated—it is 70 miles from the nearest community—but today automobiles can reach the region, cross the river on the ferry, and continue on through Utah’s most colorful and primeval region, thanks to Governor Herbert B. Maw and the Utah State Department of Publicity.”

Chaffin had homesteaded a 140 acre tract stretching from Hite to Trachyte Canyon in the early 1930s, some years after Cass Hite’s death in 1914. Cass had been a longtime prospector and miner in the canyon country, and spent decades in search of riches. Hite discovered the “crossing,” in the late 1890s, a shallows in the river where livestock and horses could cross the river during low water. Eventually Hite established a home and small ranch along the river. It was Hite’s enthusiasm, in the late 1890s, that helped set off a gold rush in Glen Canyon, though he never did more than eke out a living in this isolated canyon bottom. But Hite’s place also became a stopping off place for other miners —if you wanted to find a social event within a hundred miles, you headed for Cass’s homestead.

(NOTE: For much more on Cass Hite’s colorful history, read Barry Scholl’s wonderful account in The Zephyr: click here.)

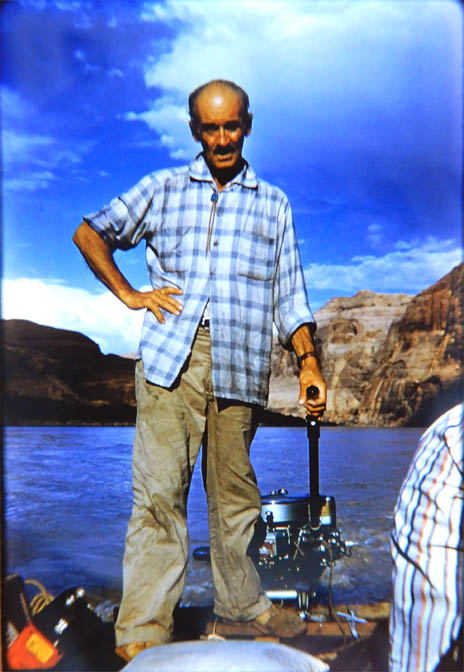

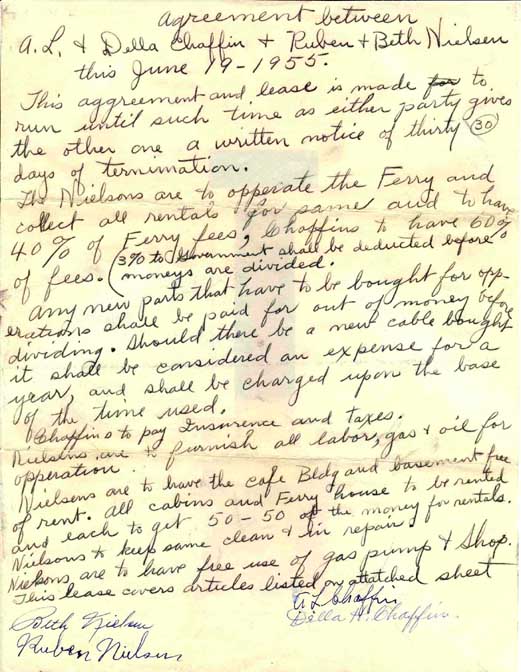

Chaffin developed his land, and as Aleson noted, his ranch was more than a hundred miles from the nearest town. He dreamed of a ferry for decades and in 1946, with help from the State Roads Commission, Chaffin’s dream came true. It would almost be kind to call Chaffin’s ferry “homemade.” It was powered by a Model A engine that was pulled along heavy steel cables between Hite and the town of White Canyon.. Still, the old ferry did its job and improvements were made to the ferry over the years.

*****

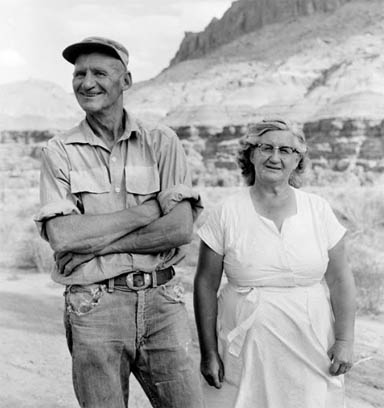

The ferry had been in operation for more than a decade when Fern and Kent decided to take a break from their long hard ride. and spend the night here at the little tent cabin that had only recently been built. They were both delighted. Fern wrote in the guest book, “You really have a little Heaven of your own here.”

The message was meant for Beth and Ruben Nielsen, the owners of a small six acre farm that the Nielsens had established just eight years earlier, along the Colorado River. The Nielsen farm was just downstream from Arth Chaffin’s Hite Ferry, but they loved sharing their Paradise with others who felt and appreciated the same unique beauty.

It was Ruben who kept the ferry running all those years. and it was Beth and Ruben that turned this remote canyon crossing of the river into “a little Heaven all your own.” The Nielsens did more than just make the desert bloom….they made it taste good too.

But few know the story of the Nielsens or the brief role they played in creating a true paradise on a small piece of land that they both loved and cherished and worked to improve— and “that little Heaven” they both knew was already doomed.

POST WAR AMERICA—”WE CAN DO ANYTHING.”

By the autumn of 1944, after six years of World War, Americans were praying that the defeat of the Axis powers was drawing near. The global conflagration had brought more destruction to the planet than any conflict in world history. Fifty million humans died; much of Europe and Japan lay in utter ruins.

With the hope of imminent peace, Americans turned to post-war America. Innovation and technology had played a major role in the war. Manufacturing plants, of a size and efficiency unimaginable just five years earlier, built heavy bombers and fighter jets that had not even been a dream in designer’s mind, a half decade before. We built ships and armaments and tanks and other weapons of war, at a rate that seemed impossible.

And of course millions of American men, and for the first time, American women, joined the armed services or the military industry to make these things happen. We had the resources, the intelligence and the will to eventually force the unconditional surrender of Axis forces and an end, after six bloody years ,the Nazi and Japanese empires.

*****

The optimism among post-war Americans cannot be understated. If we could perform these kinds of feats in war, they dreamed, imagine what could be accomplished in peace? Imagine the technology that lay ahead. Americans embraced the future with an “anything is possible” attitude. Few considered the consequences.

On October 22, 1944, LIFE magazine featured a multi page story on the future of the Colorado River. By 1945, the American Southwest was still a vast dry, and unpopulated corner of the country. Consider the population of some of today’s largest cities.

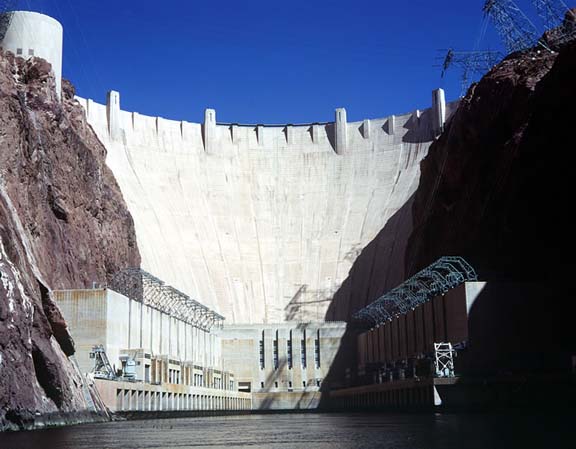

But government agencies and engineers and construction companies were already envisioning a future that would have seemed impossible just a decade earlier— projects so immense that they staggered the imagination. Yet there was already proof that when the will was there, Americans could perform amazing feats. Hoover Dam had been built a decade before the war. But it was just one dam. Now the Bureau of reclamation wanted to control the entire Colorado River, from its source to its mouth. The dream was to make the river “work for us.” The dream was to “make the desert bloom.” And the cities grow. All for the good of humankind. Very few saw it any differently.

THE DAMS

( To read a more detailed history of BuRec’s dam plans, , chick here—a Zephyr Extra was posted a few months ago called “America’s Insane Post-War Plans for the Colorado River.”)

As early as 1944, a high dam was being considered by the government just upstream from Lee’s Ferry. (As noted, so were more plans upstream and down from that site as well.. Again. Click here.)

Even as the Utah governor and crowds of celebrants cheered the opening of Chaffin’s Hite ferry , plans were already underway to make the ferry obsolete. But the notion of a 700 foot high dam flooding almost 200 miles of the Colorado River and burying Hite under 150 feet of water was almost too much to comprehend. Or even believe. Its reality seemed eons away. And it was more than that. There was something magical about the place. Something special. Surely no one could do harm to such a place.

It was to that incredibly remote, hidden Eden that drew Ruben and Beth Nielsen to Hite and the Colorado River, already knowing, though barely believing the stories, that their new home might someday be wiped (or drowned and buried) from the face of the earth. They were coming to the isolated canyon and the recently opened ferry to make a home for themselves. It was the ferry itself that made the dream possible, but for Beth and Ruben, it was a dream come true. Their love for Glen Canyon and the crossing at Hite was only exceeded by their love for each other. That mutual love for Glen Canyon cemented their personal connection even more. It was such a shared love that their life and their marriage, in a way, was bound together in one living breathing joyful experience. Over the years, everyone who met Beth and Ruben could feel that bond and be a part of it. Fern Frost may have called their home “a little Heaven of your own,” but the truth was, the Nielsens loved sharing Heaven with everyone they met.

THE NIELSENS’ ROAD TO HITE & WHITE CANYON

The Nielsens’ journey from their early Utah LDS beginnings, to a life by the Colorado River, is an improbable one. But a journey shaped by both Destiny and Luck. Beth and Ruben were both native born rural Utahans, both members of the LDS Church. Beth grew up in Manti and one would have been hard-pressed to find anyone born in 1905 who was of another faith. As Beth described her childhood many decades later:

“I was born of goodly parents, a loving mother whose life consisted of helping her husband with a grocery store, (a) newspaper called ‘The Manti Messenger,’ and the Manti Opera House and Pavillion.”

She was preceded by three brothers and three sisters and four more kids came along after Beth arrived. It might have been a bit crowded from time to time but her description of the family was one of happiness and sharing and caring. She attended Manti High School until 192 when she transferred to Provo and then to Wasatch Academy. Beth was ambitious–she learned stenography and “salesmanship,” and then took a course in hairdressing

In 1925, she met Maurice Evans through a mutual friend and they married the same year. They moved to Bingham Canyon and Maurice ran some apartments owned by his father. By 1930, she had given birth to four children, Maurice, Donna, and twins Albert and Wanda. As Beth described it, “my happiness was filled to the utmost” with her first baby boy and each that followed. But the marriage was bad and though it was unusual for those days, Beth divorced Maurice and moved in with her parents in Provo. She never received alimony, or government assistance.

She survived as her daughter later wrote, ”from the labor of her own hands.” She took any job she could find to support her children. Sometimes the jobs were less than pleasant, physically demanding, and required all the energy Beth could muster. But no matter how exhausting the work, she never neglected the love and care she gave her four children.

But we never know where Life will lead us next, no matter how grim or unpleasant it might seem. In April 1936, Beth took a job in a “turkey plant” near Gunnison, presumably to raise and then process them for sale at regional groceries. She might have thought life couldn’t get harder than this. But by the sheerest of luck, Beth met Ruben Wester Nielsen, an auto mechanic from Aurora, Utah. He had been a lifelong bachelor but they became friends. Beth later said that Ruben “was very reserved, clean ideals, and was very considerate of my situation. We were friends, and after six years of friendship, we would marry. I decided it would be all right, and that this would be a good father to my children,”

On January 22, 1943, Beth and Ruben were married in the Richfield Courthouse, and on July 27.Just six months later, Beth wrote that, “we happily went to the Manti Temple, to be sealed for Time and Eternity, and to have my children sealed to us”

Beth and Ruben had found their soulmates. But they had no idea what the future held. What mattered now was that they had found each other, and Beth had found a good man who loved her, and loved her children as much as he could have ever loved his own.

But they still needed to make a living and feed the children. Ruben was a mechanic by trade, and worked at the Manti Motor Company. During the war, work was everywhere and Beth found employment in a parachute factory, but with war’s end, finding work became a struggle. They leased the old Savoy Hotel in Manti and tried to make a go of it, but there wasn’t enough business to keep it going. Ruben opened a welding and blacksmithing shop in Aurora, but soon they moved to Sigurd. There was a Chevron gas station there, in need of a manager. Beth and Ruben decided to run it together. Beth wrote that she ”would keep the books and pump the gas. Ruben did repair welding, along with running the service station.”

They made a great team; their boy Albert was called to go on a mission with the LDS Church in England, and though they missed him, they were happy and proud of him. The Nielsens settled into their job running the Chevron station. They thought they might be there a while….and then everything changed

A JOB AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD.

Few people in rural Utah made long distance phone calls in 1949; many rural Americans didn’t own phones at all. There was a time when Americans communicated with each other regularly, even daily, by letter. Yesterday’s pen, paper, envelope, and a stamp you had to lick, was the way families and friends stayed in touch, and even the way business deals were made.

Ruben Nielsen’s skills as a good and reliable mechanic were well known in the southern part of the state. It’s hard to imagine when a man’s reputation for repairing an engine preceded him. But it was true; Ruben was as reliable as they came and that’s just who Arth Chaffin was looking for. Consequently, it’s most likely that a letter arrived for Ruben one day, probably at the Chevron station, addressed to Ruben and with a “White Canyon, Utah” postmark. White Canyon? It was from the man who owned the ferry and Arth Chaffin needed someone he could depend on to keep his relatively new ferry running. When the ferry broke down, travelers faced hundreds of miles of detour. Chaffin knew he needed help and it was Ruben he turned to.

No one knows for sure when Chaffin made the offer and how much time Beth and Ruben took to decide. But it’s likely they were ready to go from the moment Ruben opened the envelope. But if the letter came late in the year, they might have decided, or Chaffin may have advised that they wait until the weather warmed up. But they clearly thought of this job and this entirety new life with incredible excitement. Beth and Ruben probably planned all winter for the move.

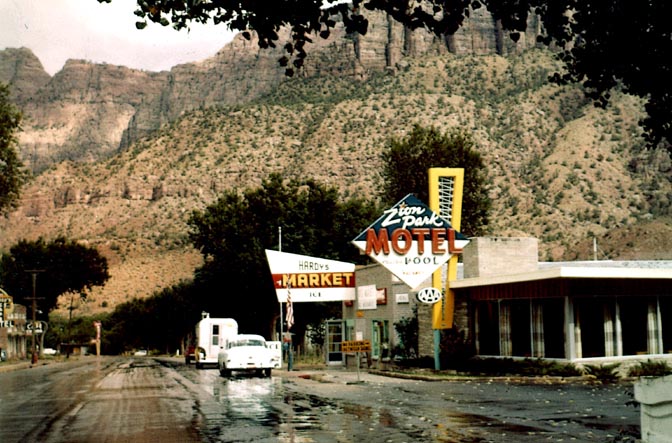

In March they started the long drive over roads that were probably close to impassable most of the time. They would have traveled from Sigurd on Utah Hwy 24, past the turnoff to Hwy 62 and Koosharem. The old road made its way to Loa and Bicknell, past Torrey and then to Hanksville and almost as close to the edge of the known world as a traveler can get.

Almost, but not quite.

Arth Chaffin himself had helped build the road south from Hanksville, across the badlands to the head of North Wash, and then down that canyon for another 30 miles. As early intrepid travelers used to say about North Wash, the running wash crossed the road more often than the road crossed it. Crossings were so frequent and sometimes so muddy or loaded down with quicksand, that there was very little reason to ever put away the shovel or the jack. It was a long ride.

The Nielsens loved to camp, so they probably made their way slowly, taking in the incredible canyons as they descended toward the river. Finally, the Colorado came into view. They followed the narrow dirt road along the north bank until they reached the Chaffin place. Arth was there to meet them.

The Nielsens set up a tent camp on the Hite side of the river just upstream from the Chaffin home. After they had settled in, Ruben began acquainting himself with the ferry and its operation. Arth was hoping Ruben was as reliable a mechanic as he’d heard, and Ruben proved his skills from the first day. For sure the ferry was an odd looking contraption, but Ruben and Arth were sure they could keep the engine running the ferry moving.

After Ruben took his measure of the ferry and the job he had taken on, he and Beth paused at their tent camp in the evening to take in the scenery. There was really nothing like it anywhere. This was Hite at Glen Canyon on the Colorado River— their adventure and a life spent in “ their own little bit of Heaven,” was only just beginning.

THIS…IS HOME.

It didn’t take long for Beth and Ruben to know that they had found their Nirvana. There was a lifetime of scenery to explore, canyons to hike, sunsets to watch and, for both Ruben and Beth, work to be done.

But more than anything, they knew that this was home. The Nielsens stayed in the tent cabins for about a year. But in the Spring of 1950, Ruben approached Arth about purchasing a bit of land from him. Chaffin been in this country since the 1930s, mostly hopinging to find gold. Though he never found the mother lode, he was able to obtain title by patent on February 15, 1943, pursuant to the Homestead Act. That patent conveyed to Chaffin a total of 140 acres.

When the Nielsens came to Arth with an offer to buy a parcel, he agreed to sell them four adjacent acres. According to the Nielsen family documents, “ Arth and Della Chaffin sold the original parcel for $1,200 as evidenced by separate agreement and the deed, which is dated May 20, 1950. The deed also expressly conveyed water rights for irrigation purposes.”

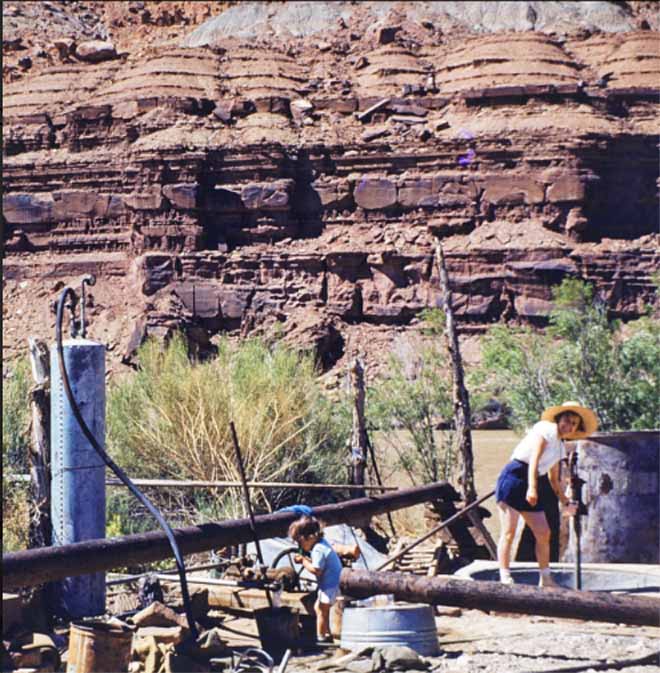

In 1954, Beth and Ruben purchased an additional two acres. Their six acre ranch was complete. Now it was time to put some of that water to good use. The irrigation made all the difference.

Leslie Nielsen remembered that, “they pumped water from the river through a pipe up to a pond or reservoir close to their property. The pipeline ran near the old schoolhouse adjacent to their property. “Ruben and my dad Gail spent a lot of time shoveling shoveling silt out of the pipe,” to keep the irrigation system working.

Again, according to Leslie, “There were two reservoirs shown on a topographic map, one of which was northwest of and pretty close to their property, but there may have been a total of three reservoirs in the area. I have seen references to multiple reservoirs in Granny’s diary including noting that friends had come over for a swim in the reservoir.”

Leslie was still in the womb when she first came to Hite but has little memories of her later visits, right up to 1963 when the reservoir began to fill.

She remembers that they called one of them, “Big Reservoir in Trachyte…One of my four or so memories of Hite includes taking a bath in the reservoir. As a little city girl, I thought it was very strange to take a bar of soap and bathe in a lake!”

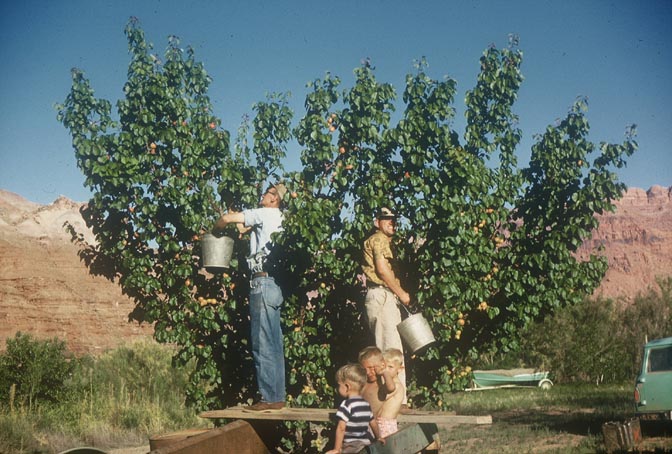

Beth and the kids, and Ruben when he had time, went to work on their dream garden/orchard/vineyard. The irrigation water from the river, was pumped up to the reservoirs, then gravity -fed the various gardens and fruit trees. It was amazing what water and sunshine can do. They began to literally see the fruit of their labor in just a few years. And of course the vegetables came even sooner, and every year.

Leslie tried to recall all the fruits and vegetables that the Nielsens grew over the years. She remembered, “watermelons, cantaloupes, corn, pears, cherries, peaches, apricots, plums, apples, even a Chinese jujube orchard, grapes, pomegranates, figs, peanuts, strawberries, beans, castor beans, tomatoes, onions,blackberries, and almonds….that’s all I can remember…and we raised guinea hens, so you could say we were a guinea hen ranch too.”

They also planted Mormon Poplars on the bottomland and the trees reached 40 or 50 feet in just a few years. The poplars were the most prominent landmarks at Hite. When you saw those tall skinny trees, you knew you were almost to the river.

The Nielsens kept planting trees, enlarging the garden, adding tent tourist cabins to rent when needed or available. One note suggested that Ruben had gone all the way to Fruita at Capitol Reef to bring back bare root fruit trees. The produce that came out of the ranch was either canned or given away as gifts to others who lived at Hite and White Canyon, and to the tourists who even in the 1950s, were starting to explore the river at Glen Canyon. They loved sharing their food and were always welcoming hosts.

There was always something to keep the Nielsens busy, but rarely anything to dampen their spirits. Except one— at this idyllic oasis at the far north end of Glen Canyon, Life thrived here like nowhere else. For everyone, it was magical.

How could it be possible that just 160 miles downstream, the US Government and its contractors were in the process of plugging the river with 5, 370,000 cubic yards of cold lifeless concrete and 28,900,000 pounds of reinforcing steel? The papers had been signed, the project approved–it was 1956 and the changes at the dam site became evident. Engineers had bored through hundreds of feet of Navajo Sandstone to create “diversion tunnels.” An artificial earthen “coffer dam” blocked the Colorado River’s natural flow and pushed it through the tunnels. Now the dam builders went to work, one small section at a time.

*****

It was like a resort and every trip we took was the ultimate party vacation!“

NEXT TIME: The World says Goodbye to Glen Canyon, Hite & the Nielsen Ranch…

Jim Stiles is the founding publisher/editor of The Zephyr. This story would not have been possible without the expertise of Leslie Nielsen, and her generous permission to use many of these incredible images from the Nielsen Photo Collection

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THE PAGE

BE SURE TO LOOK IN THE PROMOTIONS FOLDER…Gmail INSISTS!!!

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our amazing historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

https://rangemagazine.com/subscribe/index.htm

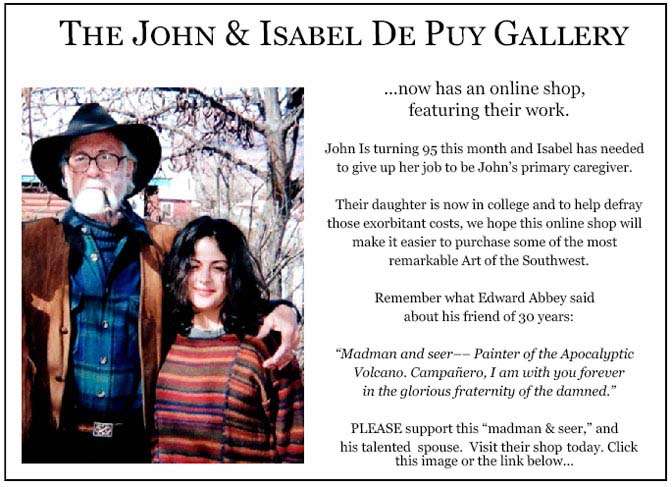

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/02/12/desolation-and-abundance-the-unexpected-comfort-of-canyon-rapids-origin-family-by-brandon-hill-zx49/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/01/22/spelunking-the-cave-that-was-buried-alive-1964-and-now-jim-stiles-zx-46/

FREE

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

What a wonderful story! How sad that Paradise was available then taken!! Those years of really enjoying the fruits of their labor, literally, would be ended! Pioneers who loved the land, took unbelievable chances in building a ferry, are few and far between these days! Imagine building their own roads over sand, mud, streams and quicksand! Thank you, Jim. for giving us this insight to history and the people who made it.

From our home in St. Louis, my parents and I would take a trip to the Southwest every summer. Our second car was a Jeep, solely for that purpose. Some time in the 50s, mid-decade I would guess, we took the Hite ferry and marveled at the Rube Goldberg nature of it. When it got caught up on a sand bar, the operator would dribble sand onto the wheel rim wrapped by the cable and the added friction would get the ferry moving again. I don’t recall the people involved, but your story brought back a lot of old memories.

Jim, another masterpiece. Monday morning I find myself reading and very much enjoying your articles. This is even before I check my emails and the latest news.

Kay

How do you get Jim’s latest before checking your emails? Is there an app, or something?

I’ve been waiting for this one, Jim, and I’m happy to say it’s as thoroughly depressing as I thought it would be.

An oasis in the desert growing “watermelons, cantaloupes, corn, pears, cherries, peaches, apricots, plums, apples, even a Chinese jujube orchard, grapes, pomegranates, figs, peanuts, strawberries, beans, castor beans, tomatoes, onions, blackberries and almonds” has been replaced with tens of millions of tons of 120 feet-deep Colorado sediment that should have found its way to the Grand Canyon and beyond.

Have you seen recent pictures of the White Canyon/Hite area? The destruction is hard to comprehend. It looks like Mars or a nuclear war zone. The lake in White Canyon, formed by the silt bank at its mouth, is now split in half by yet more sediment and is gradually filling itself in. The water in Farley Canyon, blocked by mud, stays at a fairly constant 3585 amsl – over 60′ above the reservoir that created it. The flat water of the reservoir is now over six miles downstream from there but BuWreck reckons there will a bounce this Spring. Geddit?

I didn’t realise that the Nielsons owned that precious farm or that Chaffin handed over the operation of his ferry to Ruben. I now know that Chaffin’s ranch was further downstream near Hope? Bar. From photographs, I can see the bodywork of that old Model A was stripped off at some time leaving only the power plant. Later, by ’62, the engine would be placed on the upstream side of the ferry which had, no doubt, been completely rebuilt.

Nice one, stiles. Thanks for posting.

I dig the 1934 Shell road map. “The road ended at the river.”

Loved this story and the beautiful pictures!!! Nice job, as always.

Thanks to my sister Lesli for all of your interest in Hite!

Also thanks to Jim for all of your contributions!

Diane Nielsen Kimber