Arches National Monument was created on April 12, 1929, when President Hoover affixed his signature to an official proclamation. Since then the size, status, and popularity of Arches has increased drastically, from a meager 5,000 acres then, to over 70,000 acres today. Only a handful of intrepid and adventurous souls braved quicksand, blowsand, and jagged rocks on the old unimproved entrance road to see the arches and slickrock sentinels in those early days. In 2022 more than 1.5 million visitors came to Arches.

Today, and for the last 60 years, the park has been accessible by 28 miles of paved roads and made increasingly convenient by a “modern” fully equipped campground, running water, flush toilets, and a new (to me) massive air conditioned visitor center, museum, and book store. The NPS in its wisdom even built fake sandstone walls inside the new visitor center to simulate the real canyons and pinnacles that could be seen just outside the big windows. Who needs Entrada Sandstone when you can get the same result from styrofoam?

Arches National Park has in many ways become a business, with its own mega-budget, computer room, and burgeoning management problems. The tourists swarm to the park in ever increasing numbers, seeking peace and quiet. Instead they find long lines at the entrance station, waiting lists for park walks, bumper to bumper traffic, and a campground that never empties.

Years ago, the NPS created a reservation system for the Devils Garden Campground, the place that was my home for over a decade. In the seventies and eighties, campsites were on a first come-first served basis. We usually filled by 5PM, but some nights there were still spaces left at dark. The only truly insane times of the season were Easter Week and Memorial Day. To me, it always felt too busy and l longed for the “Desert Solitaire Days,” when Abbey was the lone ranger living in the interior of the park. Other than my living quarters the similarities ended. I once wrote a story, never published, not even in The Zephyr, called “Desert Insanitaire: Twenty Years After Abbey, the Ordeals of a Seasonal Ranger.” (Maybe I should post that little rant some day, just for sentimental reasons)..

Looking back on it, I didn’t know what REAL insanity was. I didn’t think it could get much crazier than that first summer. It was 1976—the Bicentennial Year — and parks were breaking visitation records everywhere. Arches was no different. For the first time in its history, the number of tourists at Arches exceeded 300,000. Three hundred and twenty-seven thousand to be exact. That’s ten times the number of tourists that Abbey endured in his second season at the monument.

Surely , I thought back then, we’ve peaked. Pretty funny. Last year, the NPS imposed a reservation system just to enter the park, during peak hours. The park has actually been “closed” at times because the number of vehicles matched or exceeded the number of available parking spaces.

When I started the Zephyr in 1989, I had long ago given up the dream that maybe all this Industrial Tourism Madness would reverse course, or even level out. I sensed something coming and I wanted to preserve the memory of Arches the way it was.

Arches National Park has led two lives—from its creation in 1929 as a national monument, the first 30 years were lazy, quiet times, with low visitation and primitive facilities (an “inadequate infrastructure” would be the term used today to describe the old dirt roads and shacks that passed as offices).

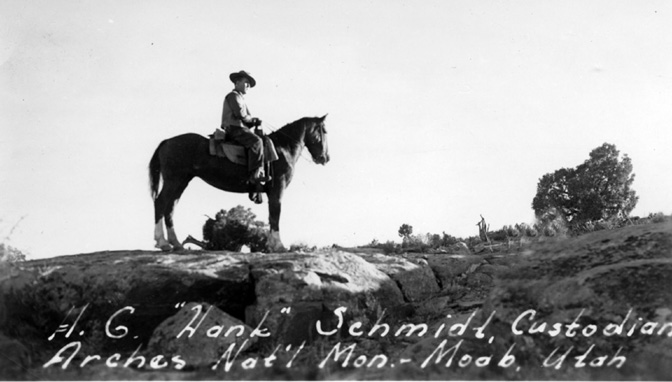

The Zephyr has published many of the old monthly reports, by the original “custodians,” as they were called. You can CLICK HERE and find many of Hank Schmidt’s reports. Every month Ranger Schmidt sent a report to the Southwest Monuments superintendent. Hank came to Arches in 1939. Within months World war broke out in Europe and it was only a matter of time before America was drawn into it. Pearl Harbor changed the world and even the future of national parks.

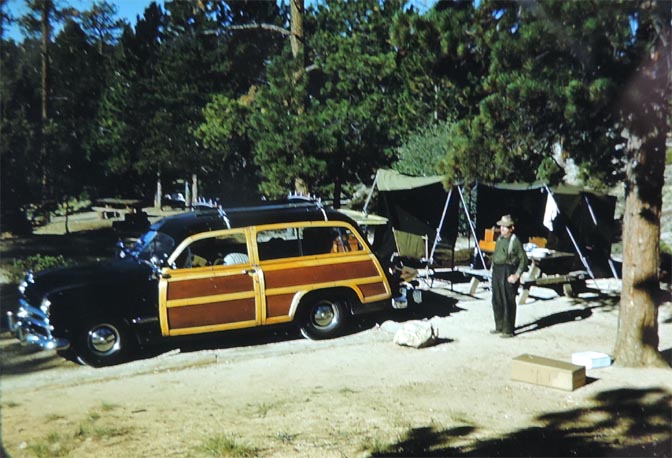

During the war, Arches was practically abandoned, but in the post-war years, especially in the 1950s, everything changed. Veterans graduated from college on the GI Bill and started families; they were earning decent wages, and many Americans were ready to hit the road. It’s important to remember that before the war, Americans and most of the world had suffered through the worst economic downturn in history. During the Great Depression, leisure activity was confined to a movie or a ball game. Very few Americans took “vacations.” Many had feared the Depression would return after the war; instead, America boomed, economically and in other ways too, of course. I was one of those Boomers. The population of the country swelled like never before.

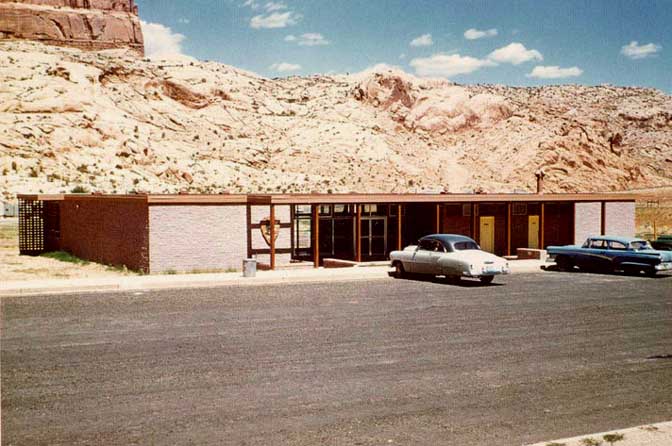

The National Parks were not ready for the onslaught and as more tourists showed up, the existing facilities were simply overwhelmed. In the watershed year of 1956, the Eisenhower Administration created “Mission 66,” a massive program to upgrade the roads and facilities at national parks across the country. It was a ten year program; with hundreds of millions of dollars at their disposal and a target date of 1966. Consequently, the parks, just like the rest of the country, were transformed.

To handle the massive increase in people and cars (“See the USA in your Chevrolet”) the government also proposed to build a massive coast to coast system of limited access, high speed roads that would supposedly decrease congestion and improve travel time. The Interstate Highway System. President Eisnhower said, “A modern, efficient highway system is essential to meet the needs of our growing population, our expanding economy, and our national security.”

The “national security” component was especially interesting. This was during the Cold War, and it was believed that a better highway system might allow the faster evacuation of citizens from large cities during a nuclear war.

*****

Easier access and improved park roads and facilities created the effect expected and in spades. During Abbey’s second season at Arches in 1957, visitation at the monument had exceeded 30,000. But just a year after the first phase of the paved road was completed, the numbers passed 100,000 for the first time.

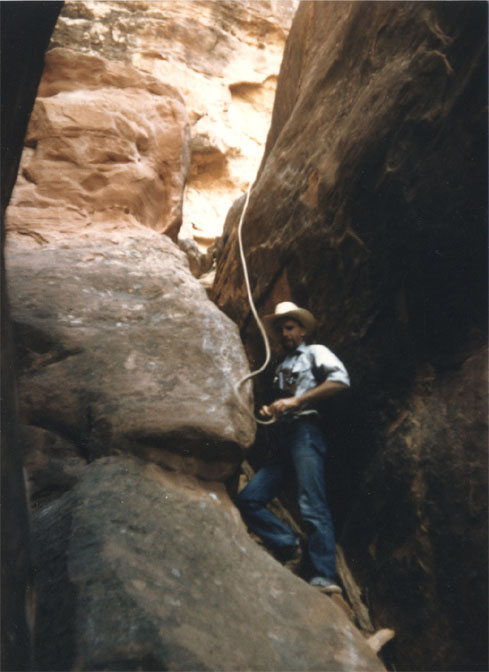

By 1989, my own seasonal ranger “career,” (if you could call it that) had ended, much to the relief of most park managers over the GS-7 pay level. But I still maintained good friendships with some of the older NPS staff, many of whom had retired years earlier but who had decided to live in Moab. I was particularly blessed to call two park veterans, Lloyd Pierson and Lyle Jamison, as dear friends. While newer park personnel loathed my irreverent, outspoken side, Lyle and Lloyd appreciated it. In fact, Lloyd’s humor was somewhat biting, and he was always willing to speak his mind, and let the chips fall where they may. He gave new meaning to the expression “unbridled candor.”

It’s why, so many years ago, I concluded that, “When I grow up, I want to be just like Lloyd Pierson.” I’m still working on it.

Lloyd Pierson was the Chief Ranger at Arches from 1956 to 1961. He and Superintendent Bates Wilson oversaw the Mission 66 project during those most tumultuous years. The building of a new road was inevitable, and so both men played a role in determining the new highway alignment in a way that would have the least impact on the park they both loved.

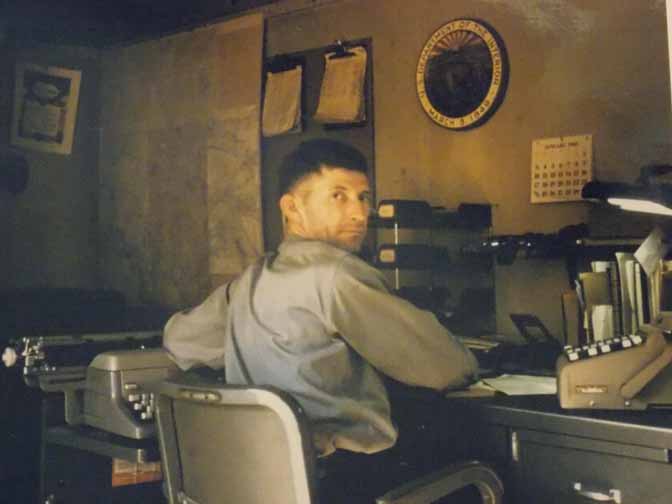

Lyle Jamison worked as the Monument administrative officer from 1959 to 1960, but as they both later explain in this story, his duties in those days were “wide and varied.” Lyle took another job in the NPS system that year, but a decade later returned to the newly formed Canyonlands National Park. It was Lyle who oversaw the hiring of seasonal rangers at Arches. I had signed on as a volunteer in the winter of 1975-76, but applied for the Arches seasonal campground job and often stopped by the old headquarters office downtown to check on my status. Using every technique possible, I told him that at volunteer pay I could not sustain myself on a diet of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Finally one day in March I poked my head in his office and Lyle looked up and grinned, “Stiley!”

He called me ‘Stiley;’ I called him Lylie.’ Are you getting sick of peanut butter yet? I nodded.

“Well…treat yourself to a chili cheeseburger at Milt’s tonight…you got the job.”

Lloyd retired from the Park Service a few years before my arrival but was a well-known face in Moab. A historian by trade, Pierson was an active board member of the Moab Museum and his frequent letters to the Moab Times-Independent were legendary. Lyle retired from government service just a few years after my arrival. But like Lloyd, he was hooked on Moab. He and his wonderful wife Lois bought a home in Spanish Valley and stayed active in local issues related to the parks.

When I decided to start The Zephyr, I was anxious to use it as a way of keeping and preserving the history of Southeast Utah. The first two people I sought out were Lloyd and Lyle. One cold morning in January 1989, I coerced both of these guys to take a ride with me through Arches to remember and recall the “good old days,” and observe the changes that have occurred over the years. We all bundled into my 1963 Volvo and I sat a tape recorder on the dashboard. I pushed the record button and off we went.. The overriding theme was: What’s changed? What’s here now that wasn’t here then? How different does this place feel to you? For the next hour and a half, they talked and I mostly listened…

For Lyle and Lloyd, the biggest change was the road. “None of this was here of course,” pointed out Lloyd as we rolled through the Entrance Station. “The paved road, the visitor center, all of it except Bates’ house (former superintendent Bates Wilson who lived in the stone house now adjacent to the visitor center), was a part of Mission 66, the big nationwide construction project to improve the facilities at parks and monuments. Actually, the first section, where it switch-backs up the cliffs was begun by the C.C.C.s (Civilian Conservation Corps) in 1939 or 1940. Lloyd remembered that the first C.C.C. camp was set up on the site of the Atlas pond, “but they must not have been here long because they didn’t get very much done.” And for good reason. In December 1941, the United States entered the war and everything got put on hold for fifteen years.

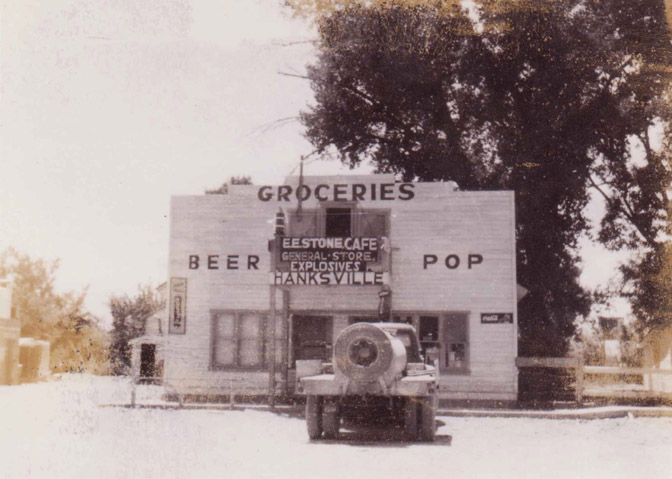

“Before this road was finished, we had to go up the main highway several miles to a turnoff just beyond Seven Mile; then it was eight or nine miles up a dirt road over Courthouse Wash and past Willow Springs to the Wayside Exhibit, about the only interpretive visitor center we had.”

The staff at Arches in the late 50’s consisted of a superintendent, a chief ranger, an administrative officer and a maintenance foreman. In addition, the National Park Service hired two seasonal rangers each summer, one at Arches, the other to be stationed at Natural Bridges National Monument in San Juan County.

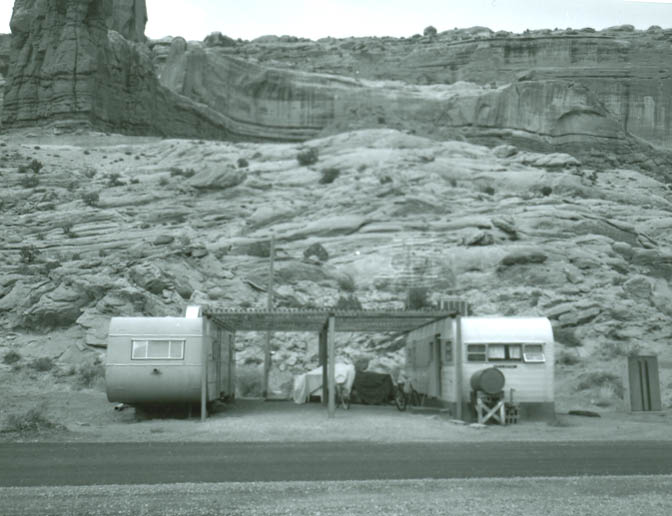

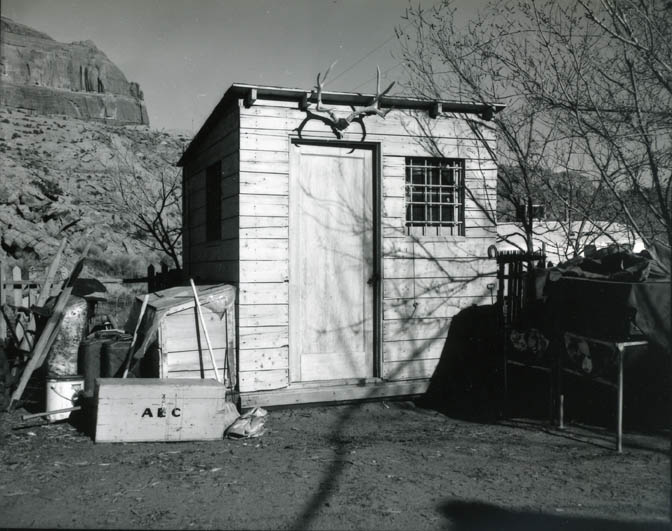

The residential area at Arches looked something like a shanty town — a remnant Hooverville from the Depression. Lloyd and his wife Marian had two kids, and when the Jamisons showed up with their four, the housing problem became critical. To remedy Lyle’s problem, the park managed to procure a couple of trailers from Coronado National Monument. They situated the trailers face to face and built a “lovely patio” as Lyle called it in between. Lloyd lived “in an old shack. Bates tied a dilapidated haybarn to the side of it as the kids’ bedroom. It was adequate.”

The work that employees at Arches National Monument performed thirty years ago has changed some. It would be unfair to say their responsibilities were specialized. In fact, it would be ridiculous to say that. “Each of us took our turn.” recalls Lyle, “at patrolling the road, cleaning the outhouses, picking up garbage and talking to the tourists.”

Lloyd recalled the trail building projects that were one of Bates Wilson’s specialties. “Bates really had my tail dragging on that trail work. He was a wiry kind of guy and could work me right into the ground. I remember once, not long after I got here, Bates hauled me out to the Devils Garden to do some trail work. He said we wouldn’t need to take water, that there’d be plenty of pothole water out there from the recent rains. Well, he was right, but the potholes were full of good stuff like deer turds and larvae, and algae, all kinds of interesting things floating in the water ….. real good drinking.

As for law enforcement responsibilities: “Law enforcement? What law enforcement?” Lloyd chuckled.

“We had a gun, I think,” speculated Lloyd.

“I think that’s right,” agreed Lyle. “But I don’t think I ever issued you guys any bullets.”

So much for crime.

Uranium & Abbey

When the uranium boom reached its peak, Lloyd and Lyle spent a lot of time chasing prospectors out of the park. “These guys never seemed to know where the boundary was,” remembered Lyle. “They’d come out here with spray paint and little red flags, spraying the rocks and setting the flags to mark the claim. Sometimes, we’d be right behind them, pulling the little pennants and rolling over the spray-painted stones.”

It almost sounded like something Ed Abbey would do. The question naturally arose; what was Abbey like?

“When I got here in August of 1956, Bates had already hired Ed for the season. He lived by himself up at the trailer near Balanced Rock. When he came back the next season, Ed had a beard. Bates took one look at those whiskers and pulled me aside, wondering what we should do. I checked the manual and there was nothing in there that said he couldn’t grow a beard. Bates figured we’d just have to live with it, and then Ed came along and shaved it off himself.”

But the beard wasn’t nearly as much of a problem as the “subversive” risk Abbey apparently presented to more conservative elements of the Park Service. “In the spring, a memo came down to us from the Regional Office, saying before you hire this man, check with us. This was the McCarthy Era, and there was a whole list of organizations thought to be Communist or subversive by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“Bates and I discussed it, and decided that when Abbey arrived, we’d show him the memo. When Ed saw it, he went straight to Santa Fe (the Regional Office) to set the record straight. I guess he did because he kept his job.”

Lloyd also recalled the size of Abbey’s head. “We couldn’t find an official NPS Smoky hat to fit him and for a while he wore a black cowboy hat. But Bates didn’t like the look of it and finally he made Ed start wearing a pith helmet with an NPS emblem. Abbey didn’t think much of that pith helmet.”

Lloyd wanted to talk about Ed a bit more, and he did.

“At the risk of taking the bloom off the good writings of Ed, Lloyd explained, “I feel I must tell ‘the rest of the story’ as that noon-time radio commentator says, (a reference to the radio news king of those days, Paul Harvey.) so that our progeny may better understand the workings of Ed’s mind, if at all possible, or at least the truth of the matter, if they are still indeed interested. The real stories are almost as interesting, though hardly as well-written as Ed’s.” Lloyd went into great detail about the book and Ed, and what was right and wrong about both:

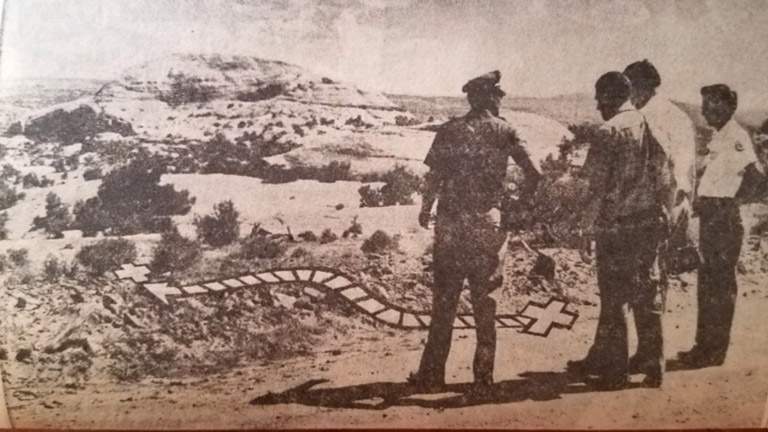

“The chapter in Desert Solitaire entitled “The Dead Man at Grand View Point” was based on a real traumatic and sad event. A gentleman from Stockton, CA, 69-year-old Clinton Kjar, parked his car off the road near Upheaval Dome so that he could take photographs of the dramatic scenery there. H.R. Joesting, a U.S. Geological Survey geologist working in the area, noticed the parked car on Sunday, August 11, 1957. It was still there on Tuesday, so Joesting notified Bates Wilson who notified Sheriff John Stocks and a search began that afternoon.

“Kjar apparently had wandered along the rims of Holman Springs Basin and Trail Canyon, a branch of Taylor Canyon, taking photographs. Feeling ill, he sat down under a shady pinyon tree along the rim, placed his camera in his lap, and quietly died in one of God’s more beautiful pieces of real estate.

“In 1957, although this was San Juan County, The Grand County Sheriff had the responsibility for law enforcement. It was isolated country, with dirt roads and no signs, as the Bureau of Land Management, who administered the area, had yet to assume any responsibility for anything but cows, sheep, and grass. The world was reading about the beauties of the area through articles in National Geographic and Desert Magazine and the restless lovers of the great out-of-doors were starting to explore a land that not many of them understood, let alone were prepared to enter and a community that was not ready to handle their type of reaction. For example, Mr. Kjar left his water supply in his car.

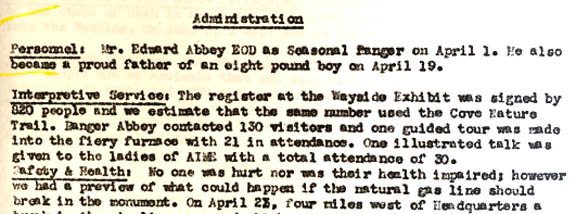

“Sheriff John Stocks was hardly more prepared than his visitors, as he had no real search and rescue organization. So he called upon Bates Wilson to provide help. This meant over two days of search, using Ed Abbey, his brother John, who was a seasonal ranger at Natural Bridges that year and in Moab on business, Bates’ son Allan or “Tug” as he was known, and myself. Tug was a volunteer college student, as were Harold Barton and Johnny Stocks of Moab. Deputy Wesley Barton, Lewis Kjar, the son of the dead man, Mrs. Lewis Kjar, Mr. and Mrs. Ben Bagley of Midvale, UT were also in the party. Most of the people were there the second day, the day of discovery. Tuesday, the party consisted mostly of the Sheriff, Bates, Ed, Tug and myself, with perhaps one or two volunteers. Wednesday I remained at the office, while John Abbey took my place

“The Tuesday party spent the day searching up and down the rim near the vicinity of the car. Tug rapelled down a fifty-foot cliff to the ledge below, seeking what we were almost certain was a corpse rather than a live, but wounded, human being. The high temperatures and elapsed time cruelly indicated this to be the case.

“Tug Wilson’s dangerous cliff-hanging was in vain, as were all our efforts that afternoon. Late in the day, I did smell a strange, sweet, rotten odor I hadn’t, in retrospect, encountered since the bulldozer accidentally dug up the dead Japanese soldier near our mess hall on Okinawa back in 1945. I was too tired out at Upheaval Dome to make any sense out of the strange scent at the time. Only later did it fall into place.

“The next afternoon at 1:30, John Abbey found the body on the rim of Trail Canyon, two miles from the man’s car. The sheriff notified the county coroner, who drove out in his hearse. Even with a liquid-proof body bag, it is a most unpleasant task to put a body in a bag and carry it, in this case, a half mile to a waiting vehicle. The desert heat and internal microbes quickly bloat and blacken a body beyond anything recognizably human. I am certain the tension of the occasion was relieved by gallows humor as Ed indicated in his version of the episode. But I wasn’t there and my feet aren’t that big—shoe size 10 ½–is that big?

“The dead man’s son was quite philosophical about his father’s passing. The old gentleman died doing what he liked to, taking photographs in a place of beauty, although I suppose he really didn’t want to cause all the trouble he did. At least Ed got inspiration and a good piece of literature out of it.

“In Ed’s version, he mentions being called from headquarters by radio to go on the search. I don’t believe we had the luxury of a park radio communication system at that time. During his second season, he had a radio out at the Balanced Rock, where he resided in a small trailer with his wife, Rita and one-year-old son, Joshua, but it only played commercial stuff and not National Park Service jargon. The only radio we had was for communication with the general superintendent in Santa Fe or Globe, AZ, or wherever he had his office at that time. It was an old Navy crystal operated set, obtained from surplus property, like much of our equipment at the time. The antenna was an aluminum pole stuck on a Coke bottle for a base insulator and guyed with other insulation wires.

“Still…Ed was a good ranger. He did pick up garbage, clean outhouses, patrol the roads picking up trash and talked to tourists in his own inimitable manner. We never had a complaint from the visitors on him. Like I said before, he did show up the second summer with a beard, but cut it off. I had told Bates there was nothing against beards in the regulations. He was blackballed by the regional office in a subtle manner that next spring when they issued a directive that anyone thinking of hiring Ed should contact them first. He must have joined some suspect organization (Sierra Club?) in those days of Senator McCarthy and his communist-hating paranoia.”

*****

Jamison reflected on his time there, especially his first tour of duty with Lloyd and Bates. “There were no specialists in the small monuments in those days. Everyone did the basics. Ever see a superintendent clean out a pit toilet today, or a ranger, or even an administrative type? No way!”

“Those were marvelous, carefree days in the 1950s, but it would have been presumptuous and bitter-hearted to have kept it all to ourselves. There were and are other almost no less spectacular places to enjoy that were not developed or on the tourist-oriented maps. People need parks, else we all get a little crazier than we already are. Lots of rangers, Ed included, felt like the park area they worked in was theirs alone and that the tourists who visited them were a public nuisance. Some of us never felt that way, even though some tourists can be a real pain at times. We tended to emphasize the ‘service’ in the National Park Service. My management philosophy was always, if the park people are not smart enough to stay ahead of the Neanderthal or non-thinking, uneducated-about-the-outdoors tourist, then he/she/it doesn’t belong on the job.”

The always candid Lloyd wanted to complain a bit more about Abbey. “Ed, in reality, was part of the problem. By writing about the wonders of Southeastern Utah, he stimulated a whole horde of nature-lovers, real and self-styled, who would love Southeastern Utah to death and others who would like to take it back to the Pleistocene. He did a better job of advertising than the local Chamber of Commerce ever did, but if Ed hadn’t done it, someone else would have; someone not so eloquently persuasive or understanding of the problems in desert environmentalism. Fortunately, some of his outdoor philosophy has stuck and struck a chord among certain segments of our population. Unfortunately, he has stimulated others who consider themselves “protectors of mother earth,” but ain’t.”

Lloyd added, “Ed was not a demonstrative person when he worked at the Arches. He always struck me as somewhat quiet and reserved with an ironic sense of humor. He loved to gig us about paving the entire monument and calling it Arches National Moneymint. His remarks in Desert Solitaire about my dreading my transfer to the cannonball circuit resulted from his finding me at Appomattox Court House one day and was a way of kidding me about being there. I actually somewhat enjoyed the appointment, although I did plan to get back to the southwest one way or the other.

And finally, in defense of his boss, Lloyd added,“Some of his characterizations of Bates were not accurate either. Bates did have a real ulcer and I don’t think he ever attended the University of Virginia….Ed always told us he was a writer and a poet, but he never bragged about his work. We took his writer talk with a grain of salt. If we had known the power of his pen, we would have had Ed writing our usually dry governmental reports rather than picking up garbage. Wouldn’t that have set the regional office on its collective ear?”

*****

By 1958, Mission 66 funds started to roll in and the road and visitor center construction projects were underway. It was hard getting used to all that money after so many lean years.

According to Pierson, “Arches survived on surplus materials from World War II and later the A.E.C. (Atomic Energy Commission). That’s how we finally got a jeep. Until then we’d use Tug’s jeep (Bates’ son) to get into rough country.

“Bates got into some trouble, because he had so much of this surplus stuff. He’d been poor for so long, that he just couldn’t resist all this stuff. I think the epitome of Bates’ habit of latching onto surplus, is when he came in one day with four or five sheets of quarter-inch thick stainless steel. He was going to make grills, until we found out that nobody knew how to weld stainless steel. That stuff was worth a small fortune, but I don’t know what they ever did with it.”

With the new construction came new problems, a taste of things to come. For starters, Bates, Lloyd and Lyle found themselves in the middle of a labor dispute. During the summer after work began on the visitor center, Bates and his son Tug were laying water line, when a large Cadillac rolled up. Dressed to the nines, the car’s occupants asked to see these two guys’ union cards. Bates bristled — “I’m the superintendent of this park, this is my son, he’s working for nothing and we’ll do what we want.” The union men retreated.

Later the Cadillac made a second appearance. According to Lyle, “these guys looked like they came from the Mafia. They represented the Iron Workers Union from Salt Lake City. One of them was about six foot four and three hundred pounds. The contractors were using non-union labor to place the steel beams and the labor bosses weren’t too happy.

By 1959, the first nine miles of paved road were completed to Balanced Rock, and a short time later, the new visitor center opened for business. Visitation began to climb and has never stopped. By 1961, over a hundred thousand tourists came to Arches. Today’s annual visitation approaches two million. With all that success, perhaps it was inevitable that bureaucratization of the park would follow. Still, both Lloyd and Lyle take a dim view of today’s Park Service …

Jamison, even in 1989, complained that, “the Park Service is bloated, overextended. Everybody has office jobs, and nobody is in the park. It’s just a big bureaucracy, and that’s a shame. It used to be that we knew everybody in the Park Service; we were like a big family, and our paths crossed all the time. Now, it’s a faceless organization.”

at the far left end of the arch is Ranger Pierson (photo credit: NPS)

Lloyd Pierson predicted that some day when the Park Service will have to split itself up into smaller units before it sinks under its own weight. “They need to break it up into Natural Areas, Historic Areas, and then these damn Recreation Areas. And stop transferring people back and forth between them. Pick your field of interest and stay in it. None of us who wanted to be in a natural area felt that working in some horrible place like Lake Powell was anything like a National Park.

“The other problem with the Park Service is their management attitude. They want to manage everything, and sometimes the best way to manage is to leave it alone. Sometimes you’ve just got to sit on your butt and not do a damn thing. Let Nature take its course … the Park Service doesn’t understand this. Mother Nature has been doing the job for four billion years. Sure, the Park Service can and should protect these places, but Nature really doesn’t need a helping hand. Only Time.”

*****

In the years to follow, I would see both men often, though sadly, Lyle died way too soon, in 1992 of cancer. He and Lois had even invited me to housesit for them when they took their annual winter vacation to warmer climates. (Though Lois was not too thrilled with the dog hair Muckluk left behind, even after I vacuumed the place twice. Muckluk shed more than any dog I have ever seen. She didn’t shed–she molted.)

But I thought Lloyd would live forever. Once, when Lloyd was well into his 80s, we hiked out to a famous inscription in the park that I had discovered in the late 70s. It was a good eight mile round trip and he never missed a step. Lloyd got me involved with the museum for a while and I even illustrated the cover a couple times. Best of all, I recruited Lloyd to write a series of historical pieces for The Zephyr over the next decade. They are listed with hot links at the bottom of this story.

In the last few years, a few of the NPS veterans gathered at the Moab McDonald’s for coffee–every Wednesday morning as I recall. They included the former park superintendents Pete Parry and Harvey Wickware, and chief ranger Jim Jones. Whenever I was in the area, Lloyd always invited me to join them. Those gatherings eventually led to a cover story I wrote about Pete, another hero of mine, and it was an honor to spend time with all of them.

But over the years, we lost one man after another. Pete died, then Harvey and finally against all odds, Lloyd Pierson, the man I still want to be when I grow up, finally left us. His mind however was as sharp and funny, and acerbic as it ever was. If anyone could ever say that a man’s spirit lives on, it would have to be Lloyd Pierson.

When W.C. Fields once heard of the passing of another good friend, he sighed, “The ranks are thinning.” For me, nothing could be truer. These were the people that made life interesting. Wherever you are, Lyle and Lloyd, we miss you guys.

*****

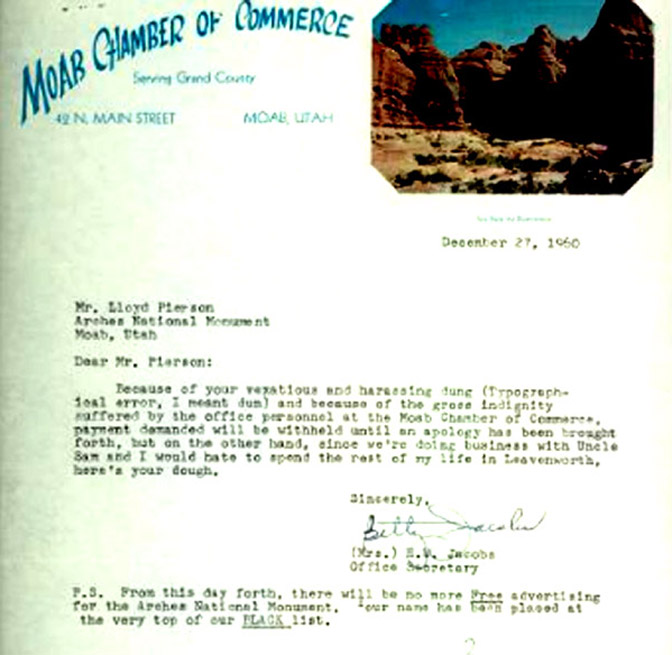

POSTSCRIPT: Recently I came across a National Archives website that was devoted to images of Moab, Arches and the Canyon Country, all shot during the summer of 1972. But among all the photographs, everything from natural landscapes to photos of the Atlas Mill, there was one letter, from Betty Jacobs at the Moab Chamber of Commerce, to Lloyd, c/o Arches NM. It is dated December 27, 1960. Why the National Archives deemed this worthy of their collection, I don’t know. But if there is any doubt about Lloyd’s acerbic wit, it wasn’t HIS words that stand out here, but instead, this response from one of his ‘targets.” In truth I have no idea if Betty’s reply is sincere or as tongue-in-cheek as Lloyd’s might have been. But in any case, I found it so “print-worthy” that I offer it here…Lloyd really knew how to stir the pudding….and I might add…so did Betty. I miss them both…JS

Jim Stiles is the founding publisher and editor of The Canyon Country Zephyr. He can be reached via Messenger or at his email address: cczephyr@gmail.com

“Clinging Hopelessly to the Past since 1989“

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THE PAGE

You can still “like” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our amazing historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

https://rangemagazine.com/subscribe/index.htm

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

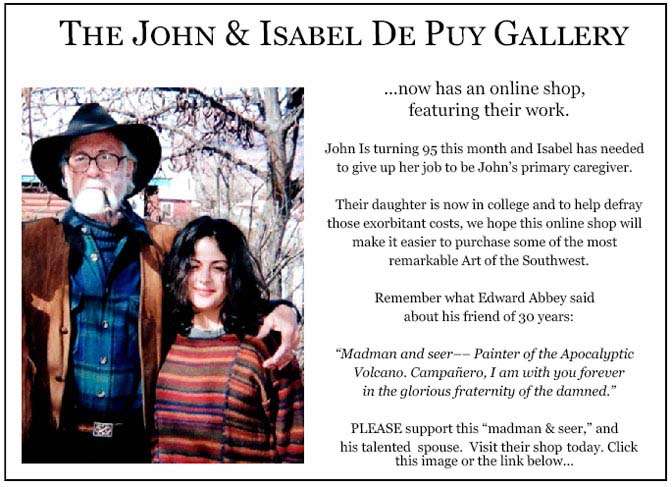

Six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned. ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

NOTE: The story below, about the terrible events of July 4, 1961, has been read by almost 20,000 Zephyr readers. I am hoping that new information from the U.S. National Archives may be forthcoming in the next few weeks. Hopefully they will shed even more light on this enduring tragic mystery….

Please take the time to read this updated story and the original version , and the story just below from the Aragon Family perspective— they are very long and detailed narratives, so choose a time when you can devote your full attention to them…

Thanks, Jim

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/03/26/update-the-7-4-61-dead-horse-murders-the-forgotten-victims-jim-stiles-zx55/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/01/29/herb-ringer-zion-bryce-1946-1965-the-complete-collection-zx47/

Jim Stiles (ZX# 46)

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/01/22/spelunking-the-cave-that-was-buried-alive-1964-and-now-jim-stiles-zx-46/

w/Jim Stiles

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/03/19/herb-ringer-his-love-for-the-rural-wests-small-towns-1940s-50s-volume-1-zx54-w-jim-stiles/

(My Recent Encounter with the Mental Health Industry) ZX#20

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/08/07/grief-meets-orwell-the-cuckoos-nest-by-jim-stiles-my-recent-encounter-with-the-mental-health-industry-zx20/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/12/25/chasing-charlie-steen-the-dream-of-uranium-riche-by-brett-hulen-zx42/

Jim what a great read. I did not know any of these people yet you bring them alive in these stories. I wish when I was at Arches in 73 and 74 I could have met many of the people who had created the experience I enjoyed. While I did not get to have the experience of the 50’s (still in elementary school in Ohio!) I certainly felt I had hit the jackpot for a quiet zen like experience when I made it there. I have refused to join the hordes of the last several years. I miss the places and although I still live in Utah I cannot bring myself to join millions in the quest for a peaceful nature experience! I move back to Ohio soon and end my 50 years of my love hate relationship with this state. I love the back country, the deserts the mountains the back roads..but I hate that now I have to drive for hours and through beige housing developments just to get to the west desert which used to be a Sunday drive for us. It is great and yet sad to read about how it was. I wish more of the hordes understood the value of what they are seeing instead of the 15 minute driveby.

This is a compelling read. What I most love are the “true” accounts of Ed Abbey’s stories as told by Lloyd Pierson. The grimly poetic “Dead Man at Grand View Point” is one of the most memorable chapters in Desert Solitaire, but this telling adds depth to an already profound tale.

I remember visiting Arches countless times during the 1960s and early 1970s with my dad who had mining claims outside the Monument boundaries to the east. Typically, we would check on his claims then go spend a day wandering around the arches. I remember very few visitors at the time, and I recall running into rangers on only a couple occasions near the Devil’s Garden campground. Two things occurred in the early 1970s that really blew up visitation and marked the end of solitude for the Arches; it was named a national park, giving it equal status as a “must see” with Yellowstone and Yosemite, and vacationing became a “must have” aspect of the American dream. Almost as important as a nice home and a nice car, vacations and outdoor recreation–hiking, rafting, rock climbing, sightseeing–became symbols of economic prosperity. Vacationing was an important requirement for “keeping up with the Joneses.” America’s cultural landscape underwent seismic changes during that era, and the West’s high desert wonders were not able to escape the tremors.

hello Jim

I was in on some of this when I started at Arches in 72. Lloyd Pierson was retired but I remember him active with the museum and I associate his wife with a quilting project the museum did, when I made a square! Lyle Jamison was still working and Tuck and I enjoyed him and Lois. And when I showed up with some friends that winter, Jamisons put us up at their place in Spanish Valley. It was -20 degrees F and snowy- a beautiful time, but we sure were grateful for inside accomodations.

The first ‘dust-up’ I remember was when I’d just arrived at the park. Some yahoo had tried to drive to Balanced Rock on the old road which was no longer a ‘road’ and got stuck. I went out with Lyle and some others to deal with the guy.

Nice people all, and it’s fun to read the ‘rest of the story’

My respect for you, Jim, was increased knowing you’re worthy of the disdain of Moab City bureaucracy. Libel? Slander? Their worthiness of these was made by their own hands. Good job!

Thanks Jim great writing as always!

Shannon

took me a while to get to this one, what a great story! thanks for bringing the past (and memories of an old favorite place) back (almost) alive. Unbridled Candor, love it! (of course, right? don’t put a bit on me!)