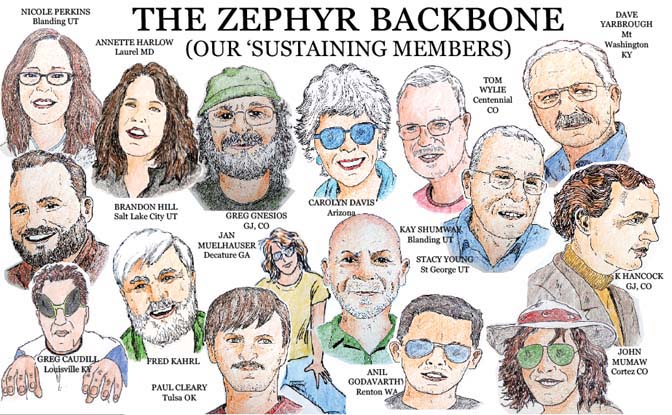

NOTE: It’s been a decade since I was first introduced to Harvey Leake and his extraordinary gift for telling history in a way that captures the reader’s attention from the very first sentence. He was a Zephyr reader and he sent me an essay that he thought might be of interest to this publication. It was called “The Myth of ‘Progress.'” He was absolutely right, and since then, I’ve posted many more stories by Harvey; I’m pleased to re-post that first essay this week, with additional photographs. At the end of this story, I’ve added a link to ALL of his Zephyr contributions, a Zephyr/Harvey Leake bibliography of sorts. I’m hoping he’ll have a new story for The Zephyr in the coming months…JS

“Progress” is a word that gets bandied about with increasing regularity. Its usefulness in describing movement toward a desirable goal is often clouded by proponents of various causes who use it without describing exactly what their proposed goal is or explaining why they think it would be so desirable. This is often the case when the word is used to represent hoped-for societal change. The advocates of such change find the word particularly beneficial when they want to avoid full disclosure of their intended means and ends, skirt any discussions of the negative ramifications of their objective, and summarily dismiss contrary ideas as inferior and deserving of no further consideration.

It would seem that progress, used in this sense, would reflect a multitude of meanings as viewed through the eyes of each beholder. Surprisingly, though, just about everyone, regardless of social background or political persuasion, is passionately marching in lockstep toward the same fundamental vision of social change, like the pioneers in a famous nineteenth century painting entitled “Spirit of the Frontier”. It depicts the westward movement of a floating goddess and her followers who, aided by technology, are clearing the way of wild animals, Indians, and darkness. Cultural critic Neil Postman, in his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, describes this concept of progress thusly: “all Americans… believe nothing if not that history is moving us toward some preordained paradise and that technology is the force behind that movement.” Henceforth, I will use the capitalized form—Progress—to represent this particular ideology.

An inevitable corollary of the philosophy of Progress, it seems, is that there is something wrong with those who are disinterested in or critical of this quest for technological nirvana. Such people are dismissed as unenlightened, backward-looking, and inferior both intellectually and morally. They are disregarded, ridiculed, and sometimes dealt with using more violent means. I became interested in this subject years ago while researching the history of my ancestors, the Wetherill family of Mancos, Colorado. They experienced this repression first-hand when, informed by their Quaker heritage, they attempted to spread the word that modern society could learn important lessons of life by studying the ways of Native Americans.

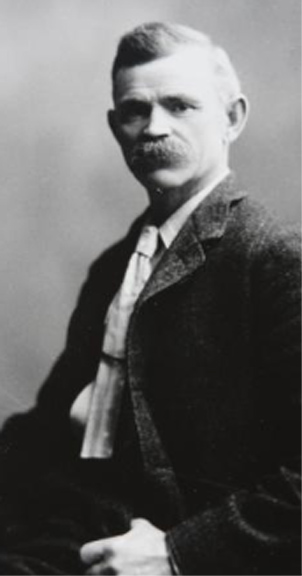

The Wetherills moved to southwestern Colorado around 1880. It was a period when most of the settlers considered the local Ute Indians to be adversaries and impediments to civilization. The Ute presence limited development of the region and expansion of mining, farming, and ranching operations. The family patriarch, Benjamin Kite (B. K.) Wetherill viewed the situation from a different perspective. He had lived with the Osages during the previous decade and respected their ability to live happily in their natural environment. Rather than fighting with the Utes, the Wetherills treated them as neighbors.

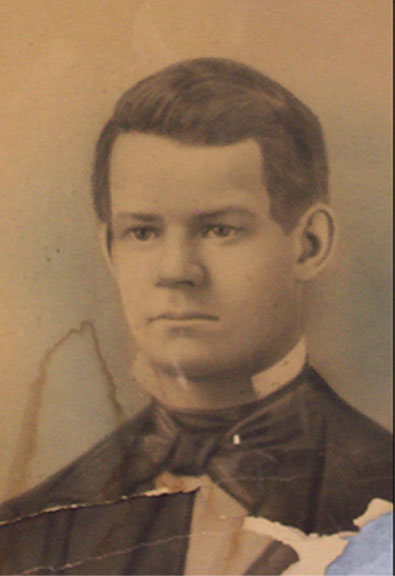

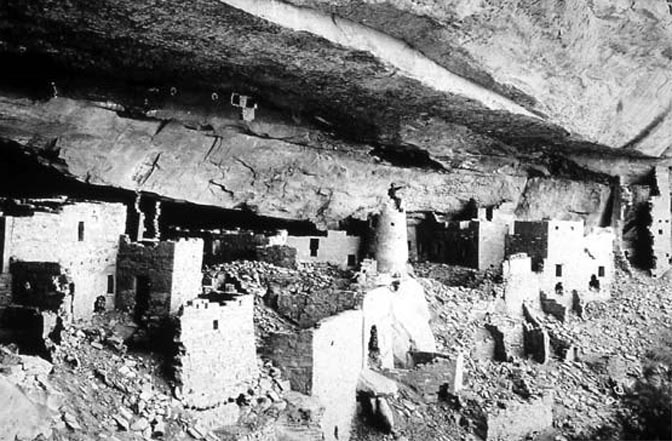

In 1888, B. K. Wetherill’s eldest son, Richard, and son-in-law, Charlie Mason, discovered Cliff Palace and some of the other cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde. The family believed that they had found an amazing resource for educating the public, and they worked hard to gather artifacts for use in spreading the message. They were disappointed when they realized that the public was not so enthused. “The neighbors ridiculed and scoffed at the idea of preserving the bones and pottery of a lot of old dead Indians,” one of B. K.’s granddaughters recalled. “Better leave them alone; they would do no one any good; why go to all the trouble?”

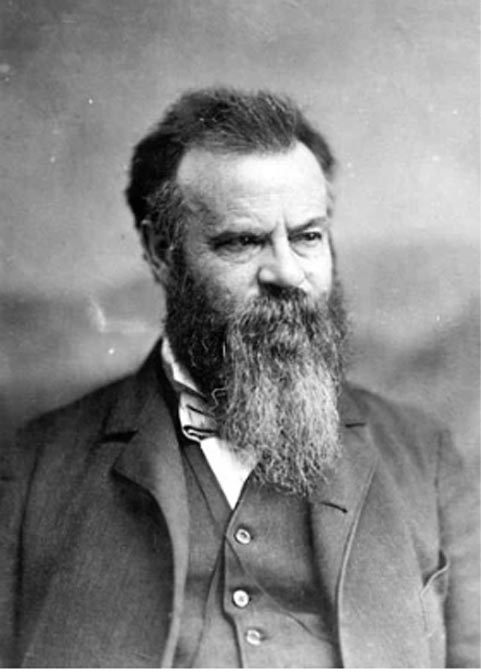

B. K. Wetherill decided to appeal their cause to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. “I think the Mancos, and tributary cañons should be reserved as a national park, in order to preserve the curious cliff houses,” he wrote. The Secretary of the Smithsonian, Samuel P. Langley, forwarded B. K.’s letter to the Director of the Bureau of Ethnology, noted Colorado River explorer, John Wesley Powell. Powell directed the letter to his staff archaeologist, William Henry Holmes. “Of course it is a pity that they could not be reserved and preserved,” Holmes replied, “but when their multitude is considered—they cover a good part of four States and Territories—it seems a Herculean task.”

B. K. Wetherill wrote several other letters, reiterating the need for government action. “We are particular to preserve the buildings, but fear, unless the Gov’t sees proper to make a national park of the Cañons, including Mesa Verde, that the tourists will destroy them,” he warned. He was unaware that Holmes had decided to terminate the dialog at the outset. “There seems to be no need of other communication with him,” Holmes had recorded privately upon replying to B. K.’s first letter. My ancestors must have wondered why a government bureau that was created for the purpose of studying Indian culture was so disinterested in helping protect invaluable archaeological resources such as the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde.

I wondered the same, so I undertook a study to better understand what the leaders of the Bureau of Ethnology were thinking. I learned that they were staunch believers in Progress, which they viewed as incompatible with the concept that valuable insights could be gained from exposure to Native American culture.

John Wesley Powell was a disciple of social theorist Lewis Henry Morgan whose book, Ancient Society, or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery Through Barbarism to Civilization, was published in 1877. Morgan wrote that human culture evolves and progresses through these three stages. He purported to document the “Growth of intelligence through inventions and discoveries,” thus asserting that non-technological cultures are intellectually inferior.

Powell elaborated on Morgan’s theory in two articles: “From Savagery to Barbarism” and “From Barbarism to Civilization”. He maintained that civilized society is not only technologically and intellectually superior, but morally superior as well. “In savagery, the beasts are gods; in barbarism, the gods are men; in civilization, men are as gods, knowing good from evil,” he wrote.

The position of these men and many others in the Federal Government was that Native Americans were stuck in the barbaric stage and needed to be civilized. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, since their inception in 1849, implemented a number of unsuccessful strategies to bring the Indians “up” to modern intellectual and moral standards, while failing to acknowledge that the divide was fundamentally a philosophic one. William Henry Holmes, who had responded to B. K. Wetherill’s first letter, later expressed the violent aspect of the government approach. He believed that the dominant culture was destined predominate and that “the complete absorption or blotting out of the red race will be quickly accomplished. If peaceful amalgamation fails, extinction of the weaker by less gentle means will do the work.”

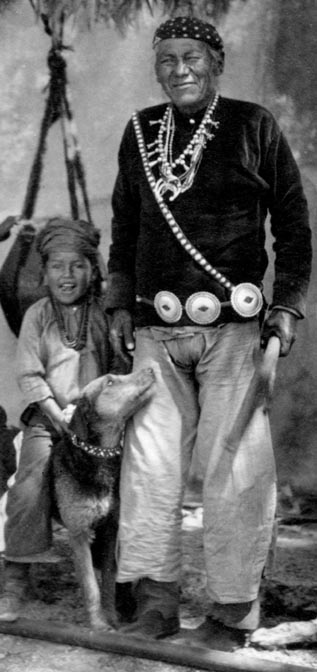

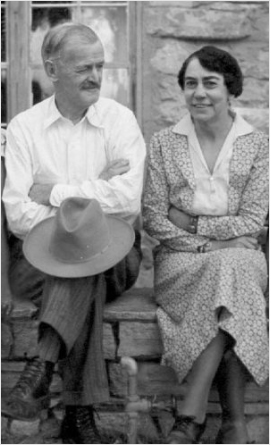

My ancestors suffered many indignities down through the years as a result of their unorthodox interest in traditional Native American culture. During their later years, all five of B. K. Wetherill’s sons spent time on the Navajo Reservation where they continued their archaeological investigations and operated trading posts. The eldest son, Richard, settled at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico where he engendered the hatred of Bureau of Indian Affairs agents William T. Shelton and Samuel F. Stacher. He was murdered by a Navajo man in 1910 under suspicious circumstances. My great grandfather, John Wetherill, lived with his wife Louisa among the Navajos from 1900 until 1944. Twice they were threatened with eviction by Indian agents who resented their acceptance of the Native Americans’ way of life.

In the course of my research, I found an assertion by John Wesley Powell regarding Progress that was particularly insightful: “It is not by adaptation to environment, but by the creation of an artificial environment.” In this short statement, Powell precisely defined the objective of Progress—the creation of artificial environments, which are a means of escape from the natural environment. The opposing view, as advocated by the Wetherills and their Native American friends, was the one that Powell rejected: we should adapt to nature, rather than avoid it.

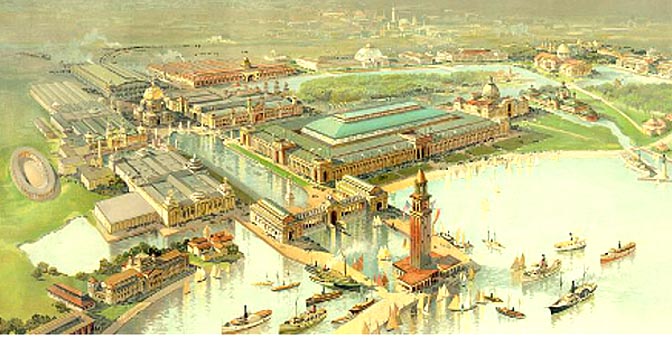

In 1893, some of the artifacts that the Wetherills had collected from Mesa Verde were exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The fair was not intended just for entertainment, but it was also a “propaganda of social ideas”, as one of its designers explained. The fair’s theme—Progress—was demonstrated by innumerable displays of the most recent advances in science, technology, commerce, and the arts. Although the exhibits of Indian materials were justified by some as contrasting with the modern and helping to illustrate how far society had progressed, others took offence that they were included at all. “[We do not] believe that any persons outside of a little handful of ethnological specialists have even a languid interest in men who were hardly above the animals with whom they were associated in intelligence,” the Chicago Tribune editorialized.

The fair’s planners, designers, and backers did not share my family’s belief that an understanding of Native American culture could help enlighten modern people. Rather, the exposition was intended to promote a higher level of refinement, culture, and sensibility, as demonstrated by the architecture and fancy exhibits. The enlightened populace could now find escape from untamed nature and their aversion to it by taking refuge in artificial environments such as those on display in the Great White City. The reinforcement of this philosophy contributed to further marginalization of the Wetherills and their Indian friends, who continued to believe in the importance of maintaining their affinity with nature.

Belief in Progress entails some of the attributes of traditional religion: Hope, i.e., anticipation of a better tomorrow, and Faith, which translates as confidence in human ingenuity and initiative to create the perceived utopia. However, it differs from traditional religion in some significant ways. For example, “hunger and thirst after righteousness” seems to have been superseded by a passion for pleasure and comfort. We repress our awareness that we are part of the natural realm and substitute the false belief that we are transcending nature, despite the inescapable fact of our ultimate fate on this earth.

The basic tenets of Progress include the quest for wealth with which to maximize ones immersion into artificial environments, accumulation of manufactured things, involvement in one diversion after another, and either hero worship or envy toward those who have made a better showing. Intentional contact with nature, if it occurs at all, often involves sanitized abstractions of the real world.

Today’s politically-charged rhetoric focuses on how to best enhance the ability of the citizens to create artificial environments. Freedom is the ability to make one’s own escape from nature with a minimum of man-made encumbrances, and equality is the assurance that all people are provided that ability.

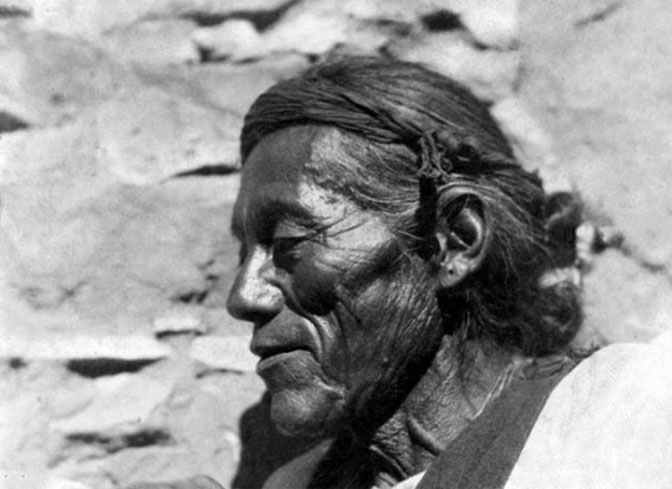

Indoctrination into the philosophy of Progress is so prevalent in our society that most of its adherents do not even recognize that an alternative—adaptation to nature—exists. I was fortunate to find, in the papers of my great-grandmother, a manuscript that explains the tenets of this philosophy with clarity. It is the account of a Navajo man named Wolfkiller who recounted the moral training that he received from his mother and grandfather when he was a boy and how it helped him deal with life as he grew older. My great-grandmother, Louisa Wade Wetherill, translated and recorded his story, and it is now available in the book, “Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd.”

Wolfkiller received his first lesson in adaptation to nature in the early 1860s when he was about six years old. His grandfather overheard him complaining about the chilling wind and gently explained that it was something to be thankful for. “All things are beautiful and full of interest if you observe them closely and study them,” the grandfather admonished. After considering this advice for a few days, Wolfkiller came to see that the wind is good. “We had thought the wind was just a useless thing to cause us unhappiness, but now we saw that it had many purposes. It cleared the air of the odors of decaying plants and dead animals, brought the clouds on its wings to give us rain, and made us strong,” he concluded.

When a violent rain and lightning storm terrified the young boy, his grandfather took him out to study the aftermath. “See how beautiful it really is,” said the grandfather. “How black the clouds are. See the streaks of white lightning coming down. See the rocks over which it has passed—how they glisten. And you can see how fresh and green the cornfields, grass, and trees are now. We needed the storm to make things beautiful.” When winter came again, Wolfkiller’s mother told him to go outside and roll in the snow. “The snow will be with us for several moons now, and if you roll in it and treat it as a friend, it will not seem nearly as cold to you,” she explained.

By following his elders’ guidance along “the path of light”, Wolfkiller achieved an intimate and rewarding connection with the earth. He so treasured the wisdom it offered that he no longer worried about his living conditions, which would be considered extreme by today’s standards. Wind, storm, cold, and even natural death, caused him little concern. His journey was not a difficult one. Simply by overcoming his unfounded fears of nature, he was able to focus on learning the skills he needed to avoid life’s real dangers and gain access to the invaluable insights that only nature can provide.

Estrangement from nature is debilitating to the younger generation in particular. Continually wired into electronic gadgetry, many children have lost their innate sense of fascination with the real world. Look into their faces as they wander the malls or big box stores in anticipation of acquiring the latest computer game, texting device, or audio or video recording. Gone is the spark of light that graced the eyes of the children of yesteryear. Today’s kids, as well as most of their elders, are missing the joys of encountering nature’s stunning scenery, the simple pleasures of sunshine, fresh air, and starlit nights, and the intrigue of discovering for themselves what is over the next ridge. Above all else, they are missing out on the lessons in wisdom that only nature can offer. These deficiencies can hardly be considered progress.

Wolfkiller told Mrs. Wetherill the story of his early training “on the path of light”

*****

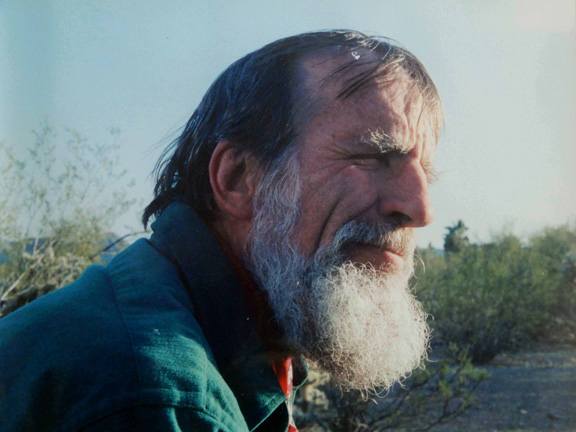

More than 35 years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer.

To read the sequel to this story:

“The Wisdom of Wolfkiller: A Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd and Sage”

By Harvey Leake (click here)

To access all of HARVEY LEAKE’S Zephyr contributions over the last decade, click here.

And finally, a link to Harvey’s book.

You can also still “like” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

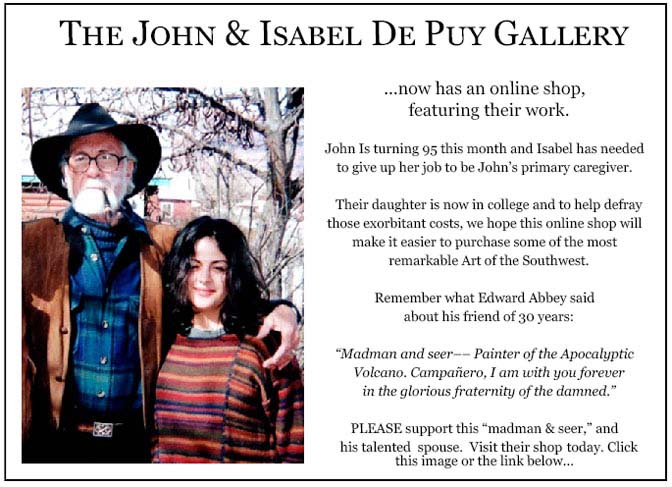

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills,

my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned. ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

The Summer 2023 issue is coming soon.

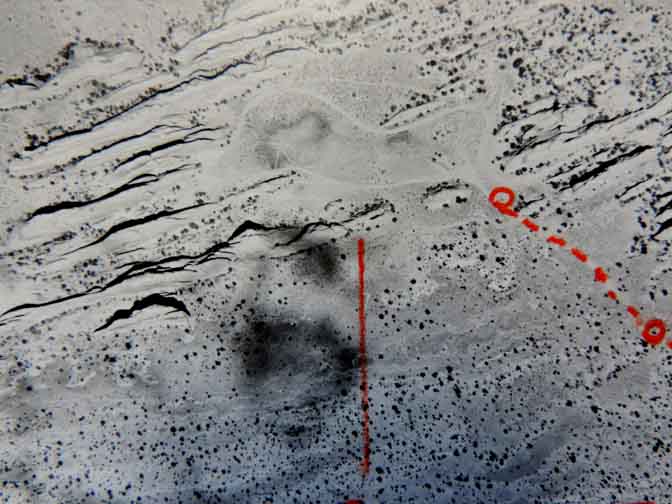

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/04/23/1957-aerial-views-of-arches-national-monument-before-the-asphalt-zx59/

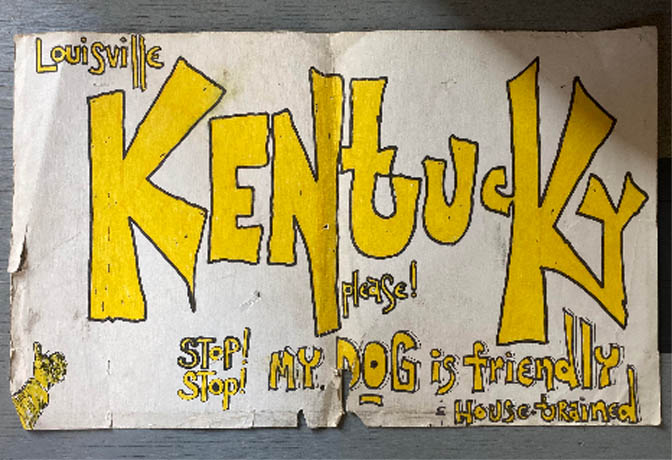

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/04/09/hitchhiking-across-america-december-1972-a-really-dumb-idea-jim-stiles-zx57/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/04/02/a-glen-canyon-album-the-nielsen-ranch-at-hite-2-zx56/

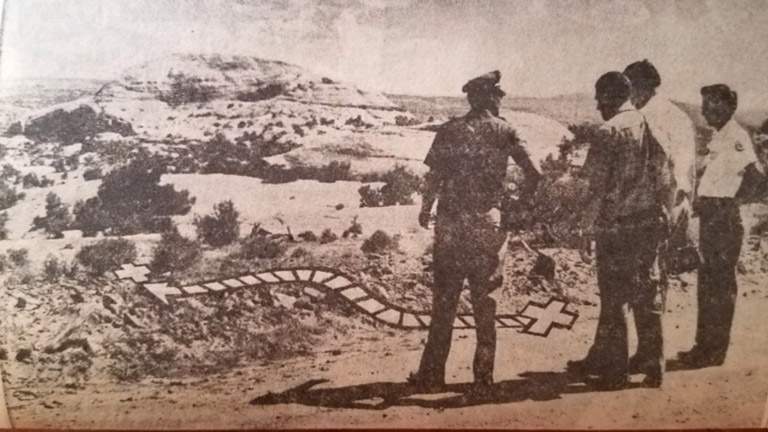

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/03/26/update-the-7-4-61-dead-horse-murders-the-forgotten-victims-jim-stiles-zx55/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

(My Recent Encounter with the Mental Health Industry) ZX#20

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/08/07/grief-meets-orwell-the-cuckoos-nest-by-jim-stiles-my-recent-encounter-with-the-mental-health-industry-zx20/

Wow! Thank you so much for reposting. I certainly missed it. And the link to all of Harvey’s submissions to the Zephyr. “Wolfkiller” is one of my few All-Time favorites. (Especially when the wind blows.) Thanks again, Jim. The Zephyr helps keep me out of the cuckoo nest. ~ : ) Gayemarie

Thanks Jim

How fortunate we who are so interested in our history, are to have people who save old histories and stories like that of Wolfkiller so that we have a look into the lives and philosophies of longgone people! Many of the traders were sympathetic to their Indian friends because they took the time to really know them and listen to what they had to say. They add much understanding to those of us who really care!

Leake has distilled many complex societal themes into one idea; that Progress is not a betterment of the human condition, but an “estrangement from nature.” I often label environmentalists who live in big cities–as most members of the activist demographic do–“urban conservationists.” They are generally political “progressives” who live in artificial environments designed by central planners to be as comfortable and convenient–unnatural–as possible. Greenbelts, with their necessary architects, builders and landscapers, are only an illusion of nature. It’s easy to see why the hivemind mentality is found more readily among young urbanites than it is among rural folks who live and work primarily in natural environments where comfort is determined by the weather, not the HVAC company. Rural Americans are generally politically conservative “traditionalists” who ascribe to ways of life that have been proven over millennia to create the best conditions in which humans can thrive. Human families with mothers and fathers who have a biological stake in their children, self-reliance, independence from government entitlements, and skill sets that perpetuate food production and tangible goods and services are qualities of rural farmers and ranchers. The arc of history, however, has been moved from its trajectory by technological advancements that allow “progressives” to unmoor humanity from nature. For instance, deconstructionist political ideologies, such as the “trans” movement, claim that the most absolute rules of human nature and reproduction can be undone by mere whim. To the traditionalists, “Progress” is a tarnished term. Many traditionalists, like me, whose parents and grandparents embraced capitalistic progress and economic expansion in the West, now wish for a return of the old ways where humans appreciated nature and adapted to its caprices, instead of trying to obliterate it.

I wonder how many readers suspicious of “progress” realize the root of the term “progressive”.

Leake focuses on and questions those dedicated to technical progress. Yes, we should always consider costs and benefits of any changes, but does anyone seriously want to live without the technical advances of the past 100 years, let alone the past 1000? You might think that people, and the rest of the biosphere, might be better off with only a few million of us living simpler, i.e. primitive lifestyles, but then 8 billion people might disagree.

And let’s turn equally critical eyes on those dedicated to social progress. Lest we forget, many of the “modern” people who disrupted native cultures in the 19th and 20th centuries were among the progressive political movements of their times. Modern progressives should take heed.