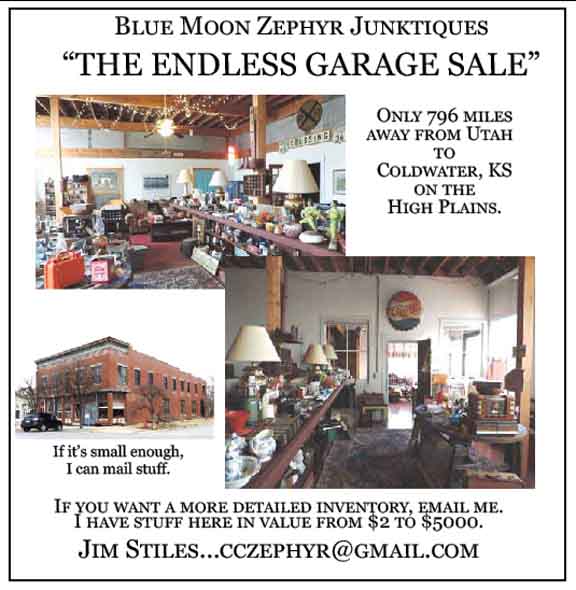

NOTE: A shorter version of this story first appeared in RANGE Magazine,

Death is not what it used to be. In decades and centuries past, Death was more the expected, than the exception. It came early and often. Death was indeed a part of Life. Babies were buried far more often than octogenarians. Parents had families of ten children, praying to God that half of them would live to adulthood. They knew there would be losses. It didn’t make the pain or the loss any less devastating — it’s just that they were ready for it, and only their faith and their courage kept them going. By circumstance or luck, young men and women grew to adulthood, or even old age. In those days, one might call it a miracle.

For decades I lived in Moab, Utah. It was once a small ranch and farm community. It faced the same kind of heartbreaking mortality as other rural Western towns. The old local cemeteries there, some long abandoned, are testament to those hard times. Death was always waiting. Farmers and ranchers pushed into new country, and tried to start new lives. They built homes and grew families and faced the same challenges their ancestors had endured.

Eventually Moab changed, like everywhere else. The Modern World arrived. And many can make a fair argument that in many respects, it was for the better.

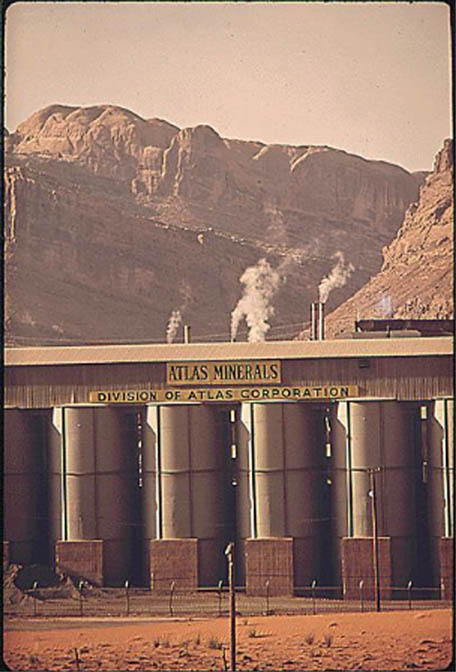

In the 1950s, the once pastoral little hamlet, known for its orchards, gardens, and cottonwood trees, became the Uranium Capital of the World. That industry brought its own kind of death and illness, though few realized its lethal effect at the time. The men and women in that industry were there for the job, and the paycheck that allowed them to support their families. The health threat was ultimately the risk they took for their children’s future. While their work was dangerous, their intentions were noble; they were willing to accept a shorter life for the good of their sons and daughters. The same could be said for the coal miners up in Carbon County. Or the steel plants in Orem. It’s a story of life and death, and risk versus benefit, from coast to coast, that has defined our country.

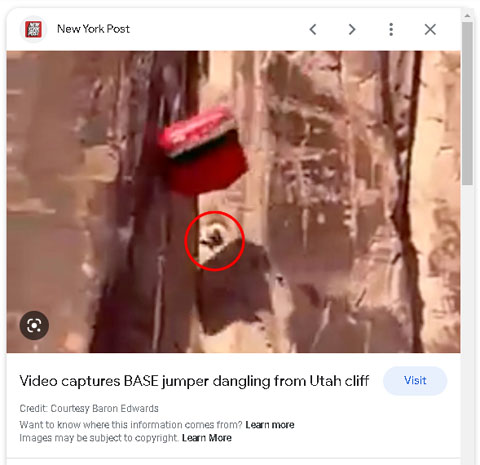

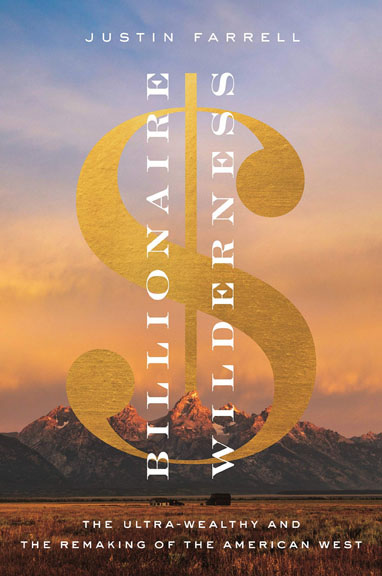

The Uranium Boom passed into history. Now Moab is something else, as is much of the Rural West. As is the country and the world. The old mining towns are tourist/amenities population centers. Theme parks. The New West doesn’t make anything, except money, of course. — it serves people and their perceived recreational needs. The New West is now the worldwide vortex for—Mountain Biking, BASE Jumping, Rock Climbing, Zip lining. Bungee jumping, white-water rafting. We call them “extreme sports.” It’s entertainment. The West is a giant theme park.

The activities that deliberately place the participant in danger — and for no purposeful reason whatsoever — are the life-blood (if you’ll pardon the expression) of the economy in communities across the New West,. For centuries, humans tried to avoid risk. Now in these shallow, empty-souled times, it seems to be the only activity that anyone finds interesting. And not just interesting, lucrative. The recreation industry has monetized senseless risk and made a fortune.

A dangerous BASE jump and a selfie—who could ask for more?

And it’s true that the number of deaths via self-indulgent craving for thrills continue to rise every year in Moab, and in “recreational centers” across the American West. Search and rescue teams are urging recreationists to carry GPS trackers or beacons, to reduce the mortality rate. Still, graves are being dug every week for young men and women who seek new ways to entertain themselves, while providing the kind of thrill that they feel is needed to give their lives meaning. Rest in Peace.

Some of us say that this is the end of the world as we now know it. But this is also the Future. In addition to the sheer folly of Death Wishes, the idea of Death is different now. Modern medicine and technology have redefined mortality. Or the extent of it. Death no longer has the inevitability that so many once assumed and feared . Now we even challenge Death—we laugh at it. We dare it on. As if Death was some kind of a joke to be toyed with. “Death Challenge— The Ultimate Game.” Recently, as AI (Artificial Intelligence) becomes a scary reality, scientists speak of achieving immortality, as the possibility of “downloading” a human’s consciousness is discussed seriously.

In 1900, the average U.S. newborn could expect to live to 47.3 years of age. In 2010, Americans can, on average, add more than 30 additional years of life, with a life expectancy at birth of 78.7. In 1900 the leading cause of death for young people under 20 was pneumonia and tuberculosis. In 2020, accidents, homicide, and suicide terminate the lives of most men and women of the same age group.

*******

It’s easy to forget or ignore the hard, brutal history that our ancestors endured and suffered, beyond our ability to imagine. For most of them, their motivation could not have been more altruistic— they simply sought a better life for their children and those that came after. Though I seriously doubt if our great grandparents could have imagined that all their sacrifice would have led to the world we find now.

But the story of sacrifice they made still survives. The hardship and the heartache, the backbreaking work, the loneliness they endured, and the loss they absorbed without a remembered word of complaint. The stories are all still there. Recorded. Documented. Forgotten. Ignored. . We pass by those documents: every day. They are permanent reminders, literally etched in stone. They are still there to remind us of that sacrifice – if anyone ever bothers to look or remember.

The next time you’re racing across an Interstate freeway at 85 MPH, or even speeding seamlessly along one of today’s four million miles of paved modern US Highways, take just a quick glance out the side window. Observe the landscape beyond your air conditioned/power steering/self-guiding/navigation equipped “covered wagon of the future.” No matter how bland or flat or uninteresting or featureless the land might appear, look closely. Sometimes, you might notice an out of the ordinary sight.

Nowadays few Americans would even give it a thought —- why is there a tiny cluster of trees in the middle of a featureless plain? We see them all the time. At certain times of the day, we might see an odd white glint of something undefinable. A misplaced rock? An abandoned car? But who cares? We race onward to the next McDonald’s or Ramada Inn. We follow our itinerary.

But out there on that tall grass prairie, or tucked in some little side canyon, or atop a wooded knoll, or in the midst of endless rows of corn, or wheat, or milo, or soybeans, or cotton— is our history. And the departed men and women that we owe so much to,.

Many of them are not even graced with a marker. There’s a good chance you’re driving over their long forgotten remains as you race along the highway.. Nothing remains. But you are surely following the same routes they chose 200 years ago—the path of least resistance. Adults and children died by the thousands. The heartbroken families buried them where they fell. Placed in shallow graves because there was no time or resources to provide the proper burial they deserved. Words were spoken. Goodbyes were made, And then they left, watching the lonely wooden cross of their precious loved one fade away along the horizon line.

But as the country grew and small communities were born across the continent, cemeteries soon followed, even before the churches and the schools. Today, tens of thousands of small graveyards lie scattered across the landscape of America. Some, even now, are still lovingly cared for. Others have long been forgotten. For the last few years, I’ve made it a goal of mine, a way of paying tribute, to seek out those old cemeteries and read what survives of the headstones. The messages of sorrow and faith and love that were inscribed in the stone still survive

Of course, only so much history can be inscribed on a piece of marble. But we can learn of long and happy marriages that withstood hardship and pain. We can see the love of their children, and sometimes their graves as well, as they surround the earth beside their parents. I marvel sometimes at the longevity of some of these graveyard residents. Men and women had crossed the Plains in Conestoga wagons, and grew old driving V8 Fords and flying in airplanes and lighting their homes with electricity, and calling their loved ones coast-to-coast. The world marches on.

Occasionally, thanks to the research of a few history lovers, we can learn more about a gravestone than it can possibly tell. They are stories that were passed along to me by good friends who took the time to share their remarkable history with me.

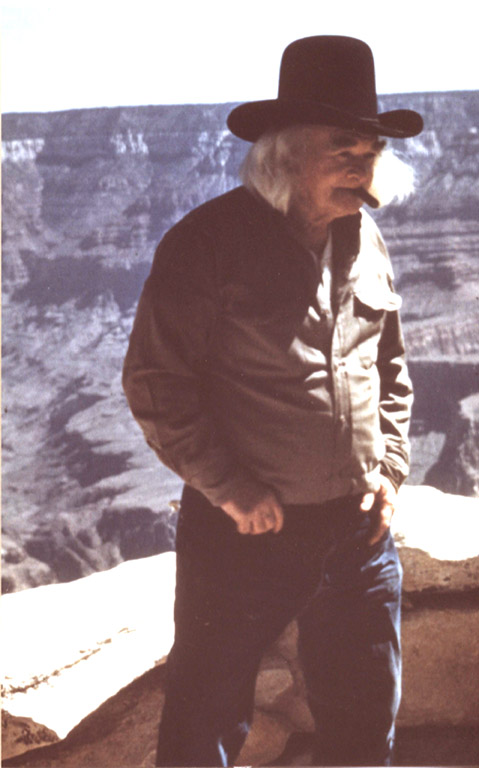

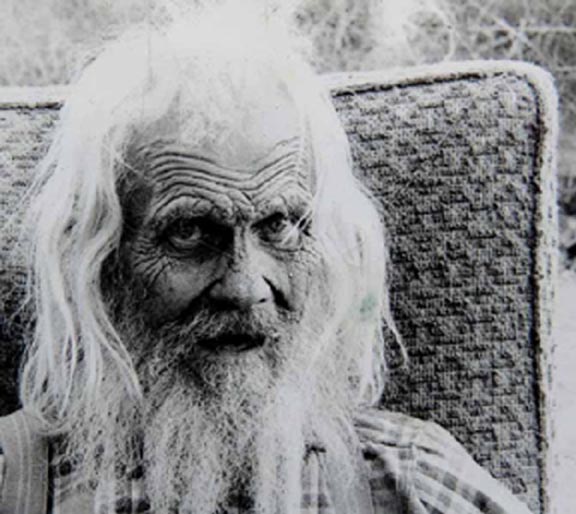

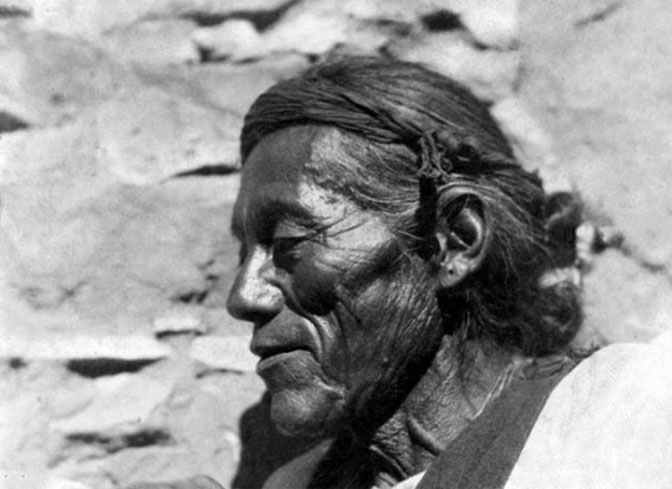

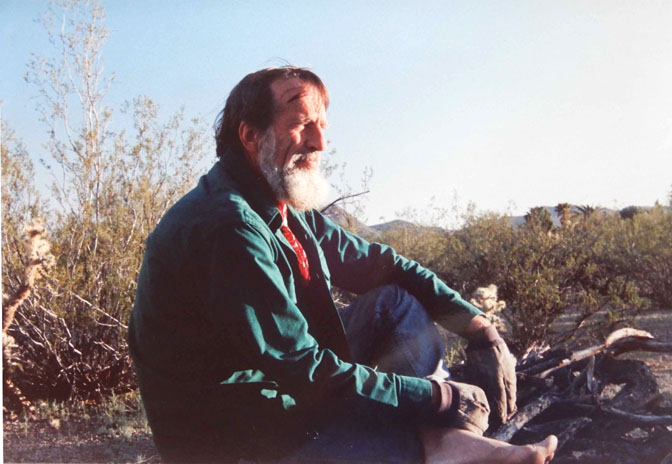

My longtime friend Herb Ringer was one of those amateur historians, who also left one of the most incredible photographic archives of the West in the mid-20th Century I’ve ever seen. Herb once showed me a photograph of a stooped old fellow, obviously standing by the edge of the Grand Canyon. Who was this fellow, I asked. This is how Herb described him

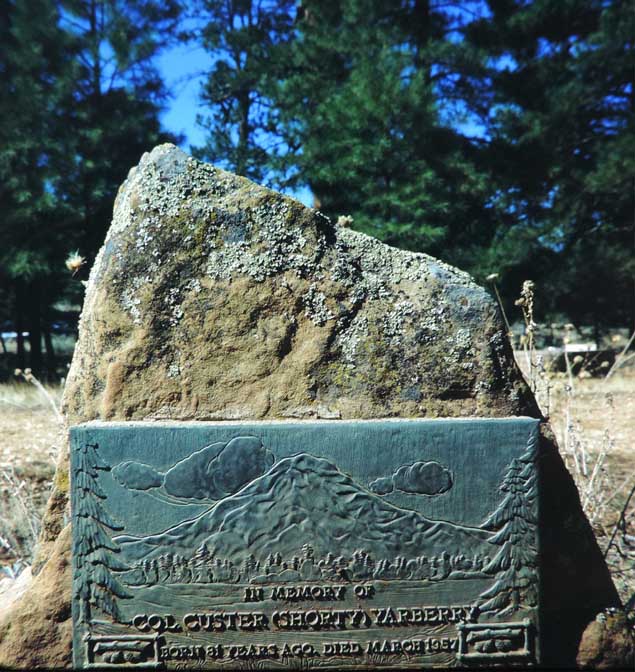

“I heard Shorty Yarberry before I saw him. I was at the South Rim store and I heard the most musical sound. I could not identify it, so I followed my ears until I saw this man with the tiniest feet I have ever seen. But on his boots, the rowels made the most melodic sound. Now I wanted to know all about him. . His whole name was George Armstrong Custer ‘Shorty’ Yarberry. He was born on the day of the Battle of the Little Big Horn when Custer was killed. Shorty had been in Texas and he was incarcerated for stealing cattle and then horse stealing. So he spent some time in a steel and concrete apartment, if you know what I mean. He came out to the South Rim and the Fred Harvey people gave him a job, down in the canyon, to erect a fence to lay some rip wrap on Bright Angel Creek. He worked with a pair of big, grey horses, and a Fresno Scraper, which is sort of a glorified wheel barrel without a wheel. Anyway he hauled all these rocks and built up the creek sides. He also planted all the cottonwood trees at Phantom Ranch.

“But the years passed and he started getting old and putting on weight. So they brought him out of the canyon…that was a task for a mule…and put him in a semi-retirement building near the corrals. I saw Shorty sitting in front of the corral many times. He was a nice fellow to talk with but like I said, he had the smallest feet on a man you can ever imagine. They say he wore a size 4. In addition he always wore Mexican rowels on his boots, so there was always jingling when he walked.

He finally died, I guess in his eighties by then, and was laid to rest in the Grand Canyon cemetery.”

Shorty died penniless, but his gravestone was a masterpiece of art and was designed and paid for by his fellow workers. Shorty was a beloved figure for decades at the South Rim.

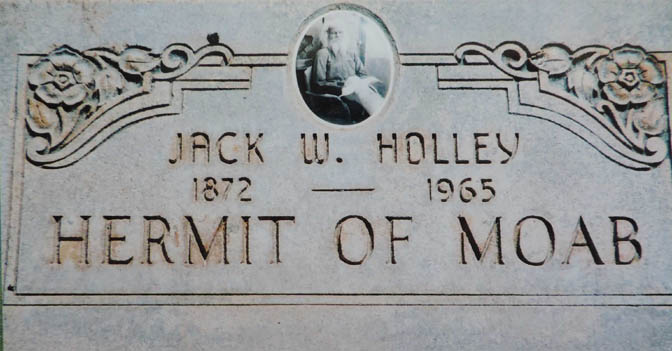

A few hundred miles north, near Moab, another man of known eccentricities, and a serious lack of resources, lived for decades in an old rock hut he built himself, just off the old highway near the Colorado River.

His name was Jack Holley and for three and a half decades, he was the first man travelers saw when they came to Moab, and the last man they waved goodbye to when they left. Jack came to be known as the Goat Man for the small herd of goats that were always by his side.

Holley lived a hermit’s life in a small stone and wood dug-out shack; he loved his peace and solitude, though he was dirt poor, even by the living standards of the 1930s and the Great Depression. His bare-bones existence meant he had no significant debts, no mortgages, no insurance payments, no credit cards, no utility bills. As far as we can tell, he paid no taxes and, other than a small veteran’s benefit check that came each month to the Moab post office, he had no income.

And yet Jack Holley seemed at peace with the world. He lived a life as simple and free from the cares and woes of the world as is imaginable. He was always happy to visit with friends and strangers alike and waved to all passersby. He loved animals and surrounded himself with his beloved goats and a family of dogs as well.

He lived mostly on the wild plants and vegetables he found along the river and, in fact, probably devoured most of the wild asparagus that once grew prolifically upstream from his cabin. And, of course, the Goat Man depended on the generosity of his friends in Moab, who regularly brought him food and clothing. He had many friends who cared about him and for him. For many Moabites, Jack Holley was ‘family.’

In the 1950s, the uranium boom resulted in a widening of the highway and the construction of a new bridge. Jack’s home stood square in the way of the realignment. But in a different world and a different time, the Utah Department of Highways, donated one of its storage sheds to the Goat Man and relocated Jack to the south side of the road, under a nice stand of ancient cottonwoods. A decade later, Jack died from injuries sustained in a fire. He didn’t have a penny to his name. But Jack had his Moab family. Troy and Juanita Anderson and their daughter Lillie were determined to keep him from a pauper’s grave. Out of their pockets, Jack not only is remembered but celebrated. He was the Goat Man and the Hermit of Moab, but for a hermit, he had a lot of friends.

There’s one more grave that deserves recalling. Not far from Crested Butte, on the Kebler Pass road, it’s easy to miss a rather eloquent marker. I’ve never learned the full story of Mary Brambaugh who may have died at that location as her family moved west. Or perhaps it was her favorite place. She was seventeen years old. Later a proper marker was left for Mary. If you look closely, you’ll see this reminder near the bottom of the stone:

“My good people, as you pass by, as you are now, so once was I. As I am now, you soon must be. Prepare yourselves to follow me.”

Few are as lucky as Shorty and Jack and Mary were, to be remembered and revered as they were, with their colorful histories intact and alive. Most remain just names and dates, often with a sweet sentiment inscribed alongside.

Last year we came across another forgotten graveyard that many Americans would prefer to forget. It’s one of the many black and shameful moments in our country’s history. Near Granada, Colorado lie the crumbling remains of what the U.S. Government called “The Granada Relocation Camp.” To its residents it was known as Amache. In 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066; it allowed the government to forcibly remove citizens of Japanese ancestry and confiscate their possessions and property,, Amache was one of ten Japanese Internment Camps established by the War Relocation Authority. The government removed US citizens to this remote location, and ten more just like it. The government regarded these people of Japanese ancestry as a threat to national security. Eventually 120,000 human beings were forcibly moved. The Amache Camp opened in late August 1942. Today it is a National Historic site. Few visit.

*********

As I’ve explored these remote graveyards, I’ve come to realize that the placement of the graves is much like the society they lived in. Often the more expensive and elegant, even extravagant, markers and statues can be found in the loveliest parts of the cemetery. The further you move from the core of the graveyard, the smaller and less expensive the headstones become. Even in death, the people knew their place. Or were forced to.

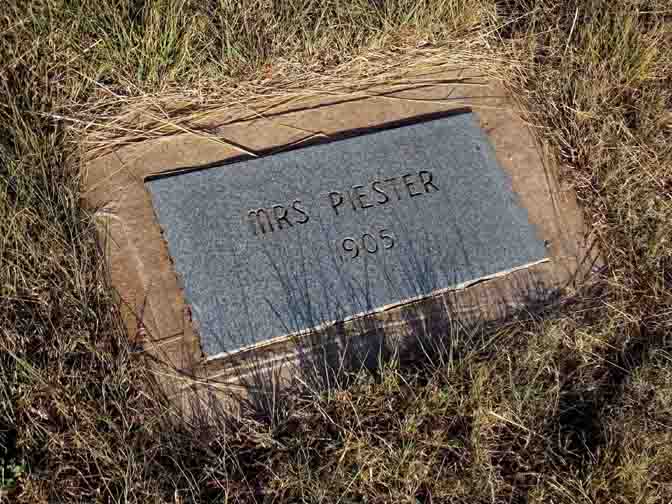

And there were other cemeteries where it was obvious poverty ruled all their lives. In places like Quay, New Mexico, or a remote graveyard called “The Lookout,” the people who buried their loved ones did their best to adorn the marker in any way they could. Many gravestones weren’t made of stone at all. They were often

created from formed concrete. Then, while it was still wet, the most artistic of the family would inscribe the name and the dates and a few words. Sometimes they tried to “beautify” the marker by pressing marbles into the wet cement. Something to give it a little color. To show the family cared. I saw other graves, where the deceased had died and been buried, and no one even knew her first name. Her marker would read, “Mrs Piester.” or “Mrs. MacCready.” Her real identity is known only to God.

But more than anything, more than the makeshift graves, or the poverty that spoke through them, it was always the babies’ graves that were most heartbreaking to see. There were so many of them. So many children died before they learned to walk. And before they had learned to read. There must have been some company in those days that specialized in infant graves. Again and again, we would see the small porcelain figure of a lamb. On it would be inscribed “Our Beloved Child,” with the name and dates of birth and death added.

There was one grave though that I can never forget.

We were exploring back roads on the High Plains, looking for nothing in particular. I took a right turn , and the road shrank to two tracks; it meandered a bit over a dry creek bed and into the sunburnt prairie. We followed it, just as the sun was starting to set. To our surprise, we found a small cemetery. A Lutheran Cemetery. Although we were miles from nowhere, it was still being cared for. A wrought-iron fence kept out the cattle, and what passed for grass had been recently mowed. As we wandered among the gravestones, we were hard pressed to find just a few souls who had been buried here recently. Yet somebody still remembers this place enough to maintain it.

Like all cemeteries, the markers told us a story. We came to recognize the prominent families, both by the number of stones and the quality of the monuments. Even now, it was clear to see who were the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots.’ We could see who had managed to live long enough to become the patriarchs and matriarchs and whose lives had been cut short. On the far eastern side of the cemetery lay the ‘have nots.’ A row of flat markers separated the poor from the more prosperous, even in death. One small marker only read, “Mrs. McCready.” She may have worked as a servant, or a nanny. She may have been entrusted with the care of a child. And yet, apparently, no one even knew her first name.

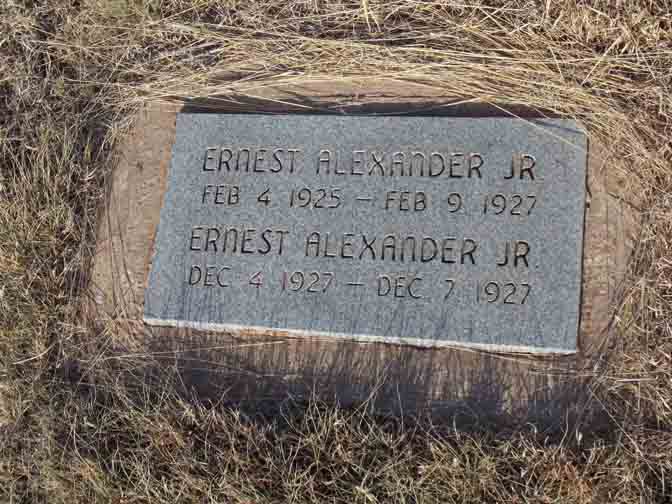

And we found many children’s graves. So many babies. But one small marker gave me extra pause. I examined the inscription carefully, thinking at first I was seeing double. On the top of the flat headstone, the inscription read:

ERNEST ALEXANDER, JR…. FEB. 4, 1925 – FEB. 9, 1927

—————Below it, these words had been chiseled into the stone:

ERNEST ALEXANDER, JR…. DEC. 4, 1927 – DEC. 7, 1927

At first we were puzzled by the two shared names. But then, as we examined the dates more closely, it became painfully apparent what had happened. Ernest Alexander and his wife had given birth to young Ernest, Jr. during the cold winter of 1925. He had only managed to live two years and the Alexanders had buried their infant son out here on this wide lonely plain. Barely a month later, Mrs. Alexander became pregnant again. She gave birth to another son on December 4, 1927, and they named him Ernest Jr. as well. He lived three days. He was buried beside his brother and a common stone was placed over them both.

We searched in vain for the gravestones of the parents but could find neither–perhaps the pain of losing two sons in ten months was more than they could endure and they left the country. I guess we will never know.

Many of us talk about getting “back to the Land,” or of living a pastoral life that we seek only for its gentle simplicity. We refer to ‘wilderness’ in such poetic, grand terms, but we never fully appreciate the brutal unforgiving wilderness—the true nature of Nature— and the burdens and hardships and tragedies our ancestors faced and accepted along the way.

I remember the lines from T.K. Whipple. He wrote:

“Our forefathers had civilization inside themselves, the wild outside. We live in the civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived, we dream.”

I think of the two Ernest Jr. babies often. I worry about them out there, all alone. on the High Plains. They have been gone for almost a century. I decided not long ago that when my time comes, I want someone to take my ashes and scatter them out there beside those two boys. I want them to know they have not been forgotten. I never had kids of my own — maybe it’s not too late to provide them a little company on this lonely prairie. Maybe—somehow—they’ll know that someone still remembers and cares.

Jim Stiles is the founding publisher and still editor of The Canyon Country Zephyr. Still “Hopelessly Clinging to the Past Since 1989.” He can be reached via Messenger or by email: cczephyr@gmail.com

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. THANKS

You can still “like” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

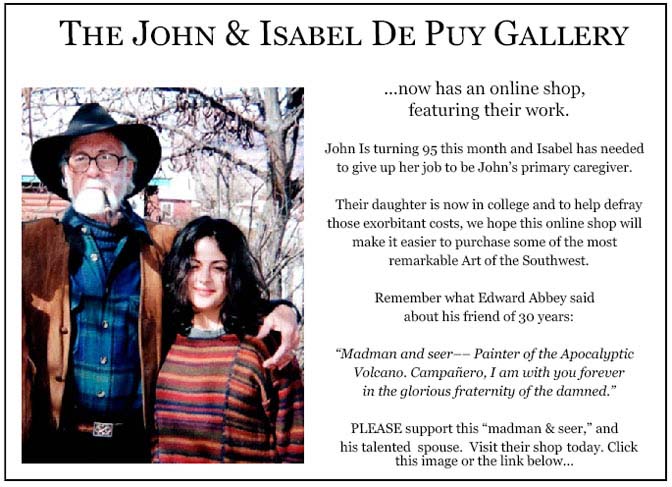

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

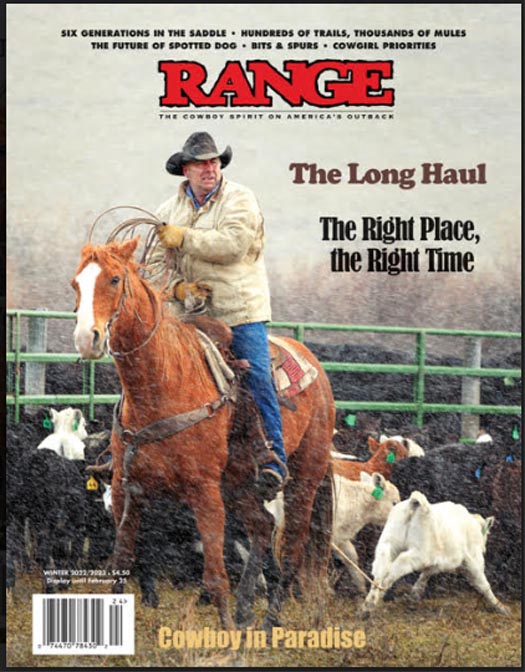

NOTE: The upcoming summer issue of RANGE includes a tribute to lifelong Moabite Karl Tangren.

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/04/30/the-myth-of-progress-revealed-by-traditional-navajo-wisdom-by-harvey-leake-zx60/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/04/02/a-glen-canyon-album-the-nielsen-ranch-at-hite-2-zx56/

—Jim Stiles (ZX#51)

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/02/26/glen-canyons-nielsen-ranch-at-hite-the-untold-story-pt-1-jim-stiles-zx51/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/03/26/update-the-7-4-61-dead-horse-murders-the-forgotten-victims-jim-stiles-zx55/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

(My Recent Encounter with the Mental Health Industry) ZX#20

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/08/07/grief-meets-orwell-the-cuckoos-nest-by-jim-stiles-my-recent-encounter-with-the-mental-health-industry-zx20/

I recently created a meme for RANGE magazine’s social media platforms. It read, “There are men and women who seek out danger and call it recreation. There are others who live with danger every day because it’s a way of life.” On on one side of the meme was the photo of someone using technical gear to climb a slickrock cliff face. On the other side was a cowboy roping a cow at a full gallop. The “extreme sports” phenomenon is a poor replacement for the rugged Western way of life that is passing away before our eyes, but which we all crave.

One saying goes, “Don’t live your life to keep from dying, live your life to live.” I suppose we apply our meanings to “an abundant life.” Younger generations–men in particular–are more detached from nature and removed from the physical dangers, discomforts and pains faced daily by those who came before us, Thus, energetic and courageous individuals naturally seek an outlet for the primal need to face down and conquer the natural world.

As you so eloquently put in the first paragraph, “Death is not what it used to be. In decades and centuries past, Death was more the expected, than the exception. It came early and often. Death was indeed a part of Life.” But death is different now. These days, few people die in blizzards or stampedes or from cholera or in childbirth an untreated infection. Suicide, intentional and unintentional overdoses of powerful drugs like fentanyl, inner-city gang violence, car crashes, etc. are the main culprits in modern mortality. As ignominious as dying from cholera might have been, can anyone say it was worse that suicide or fentanyl?

Actually the leading causes of death in the United States in order are heart disease, cancer, unintended accidents and stroke. All of these except accidents and cancer speak to our bad eating habits among other lifestyle choices we choose to make.

For children and adolescents in the United states the leading cause is now firearms which speaks to the inadequacy of our politicians to deal with the problem of unlimited guns of any kind for everyone everywhere anytime anyplace. The second cause for this age group is auto accidents which speaks to, well, I don’t know, it must be just being an inexperienced teenage driver. Drug overdoses while rising fast are still a distant third.

The average life span in the U.S. is 76.4 years and has been falling recently. In the countries of the European Union the average life span 84.378 years.I think this speaks to all of the above and our evidently substandard and definitely unaffordable Health care except for the those with more money than the average person as opposed to the health care for all model.

The incarceration of our Japanese friends was truly a very shameful event. Yet we had a Japanese classmate, Joseph “Shinji” Enomoto who joined an all Japanese/American group and fought for us and his family.

I’ve always been interested in gravestones. Interesting ones in Rhyolite, Searchlight, even Nelson tho small, tell a story. A very tiny one in Goffs, CA right next to old 66 but cared for on the property of the Mohave Museum there and it has soldiers and of course, a baby. We even had school friends who in later life published books on cemeteries across the country. Near the OK Corral in AZ is one of interest as is the one in Virginia City, NV. I hope you don’t join those two little boys too soon but I think your idea is a good, charitable one. Donna

As always Jim, an excellent article. Quite thoughtful and philosophic to be sure. Keep ’em coming Jim – you do have fans.

Thank you for writing about small neglected cemeteries, as they are very close to my heart. I’m currently involved with some locals in Boulder County, Colorado, to restore a small mountain cemetery near the former silver-mining community of Caribou. At 10,000 feet, close to the Continental Divide, the climate is harsh and only photos remain of the beautiful stones left by Cornish immigrants in the 1870s and 1880s. Our nonprofit group intends to bring dignity and respect to these forgotten miners and their families. For more info, see cariboucemetery.com.

hi Silvia–I didn’t know about this effort to resurrect (yes, pun intended) the Caribou Cemetery. I’ll check out the website.

Evan… Thanks for your interest. Some people have had a problem accessing the site, as “auto correct” tends to separate the words caribou and cemetery. If you have trouble, please try again, http://cariboucemetery.com.

Thank you, Silvia

Once again, thank you for your writing that consistently examines and honors the struggles of the common people, past and present, so often looked over and forgotten amidst the flood of online flim flam exulting the absurd,extreme and fabricated renderings of “struggle”. With humility and gratitude, su compadre, Coyote Cairns

Another good one Jim.

I remember talking to an old cemetery administrator who told me that one generation after someone is interred, no one visits that person’s gravesite. How quickly the “average” person is forgotten.

My son Zachary passed at age 20 in one of those “adventure” deaths when his anchor knot came loose rappelling Tear Drop Arch in 2013. He’s interred at the old cemetery and I visit him when I am feeling down, which is often. And he had ancestors that died at the same age doing everyday work that was also very dangerous over 100 years ago here in Moab.

I have Jack Holley’s .22 rifle (complete with melted trigger guard), some of his correspondence school papers and some of his letters and effects. Not sure what to do with them.

Hi Jim great writing as always. I feel fortunate to have found your site. Thank you.

I very much enjoy these stories and insights into life in the Canyon country.Although I have only visited the Moab area a couple of times I became enthralled with the history of the area.

This particular story connected with me as I too found an attraction to the cemetery in Sego canyon.

After wrapping up a photo workshop I was assisting in I had a couple of days to explore the area before returning home. A Google map search of the canyon had caught my eye as there are both petroglyphs and a ghost town. Half of the graves in the graves in the cemetery are from the year of the Spanish Flu while the others are at different years in the early 1900s. Coins left on the stones suggest recent visitors showing their respects.

But there is one fellow who passed away in 1995, only 49 years and 11 days old. I’m intrigued about how he came to be buried in such a remote location.

Here’s another death-related concept to ponder: how would you live differently if you could live forever?

Futurists have considered how we might behave if we cured all diseases and the only causes of death came from trauma. Would you still indulge in risky behavior if a fall or crash would rob you of hundreds of years of life? Would you tolerate ANY risk, or would you seek a highly sheltered risk-free life? IMO, some modern people already tend to reflect this, perhaps with some expectation that if they behave just right, they might live forever.

And then there is the question of what to do for all those years, presuming reasonably good physical and mental health. Almost certainly we would need to work more years, since a few decades of earnings and savings will not support an infinite retirement. What else would you do?

A nicely done meditation. Thank you.

Jim, your writing reads like a giant poem. I am lucky enough to be able to visit the graves of my paternal grandparents and my parents and the sites where Patsy and I will be buried. There is a graveyard in Spanish Fork canyon just off the main highway that I am sorry to say I drove past with a bit of a guilty conscience for not stopping to read the headstones and learn more about the people who once lived near there.