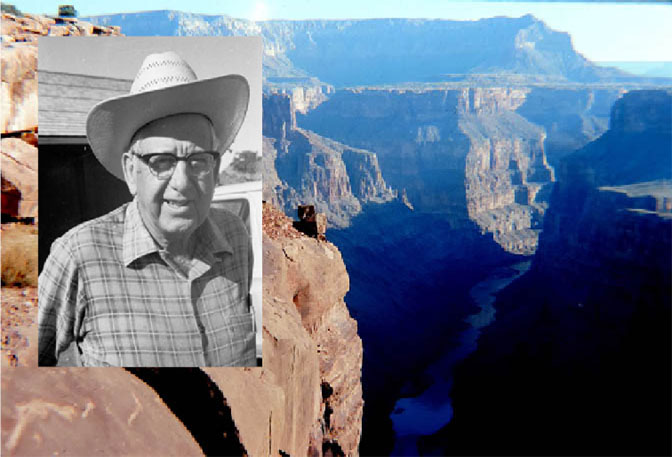

FORTY YEARS of BLISSFUL SOLITUDE ON THE NORTH RIM OF THE GRAND CANYON

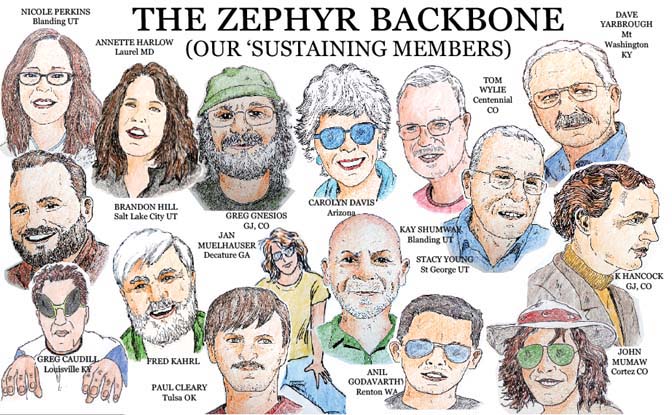

NOTE: I met Edie Eilender more than 30 years ago; she was a regular summer resident at Ken and Jane Sleight’s Pack Creek Ranch. She was a tiny woman, less than five feet tall, and I think she may have worn her hair in braided pigtails for most of her life. But what she lacked in physical stature, she made up for with her strong and candid personality. She was truly the “mouse that roared.” And I say that with the deepest of respect and affection. As the years passed and ownership of the Ranch changed, I lost touch with Edie, though she remained a frequent Zephyr commenter and a continuing member of the Zephyr Backbone. Finally, years ago, I lost all contact with Edie and often checked with friends in the Boulder/Gold Hill, Colorado area, but no one could help.

Last week, I was thinking about Edie again, and a story she’d sent me in 1996. In addition to her Pack Creek experiences, she had come to know and frequently visited Ranger John Riffey at one of the most remote National Park Service areas in the country— The Tuweep ranger station at the far west end of Grand Canyon National Park. When she sent me a story about her time there I was happy to print it.

I Googled her again, as I’d done many times over the last decade. I discovered that Edie had died on July 18, 2022. She was 87 years old. In memory of Edie, here is a redux of her story, and below her contribution, my own story of meeting Ranger Riffee on a cold January morning in 1978…JS

From the 1996 Zephyr Archives…

It is winter in the Colorado Rockies as I write this story. For months I have been fussing with wood. Gathering wood, sawing wood, stacking wood. It’s called building a wood pile so when the snow and cold arrive, I can unbuild it, carrying it, log by log, into my house to be burned.

In my wood pile I have some pieces of antique wood, some logs that I never seem to burn. They stay there year after year. These antique logs escape the fire because they hold memories. They talk to me of the past and the past lives in them. Perhaps the day will come when all the other wood is gone, the cold will be in my bones, and I will cast sentimentality aside and carry these antique logs to the fire to be consumed.

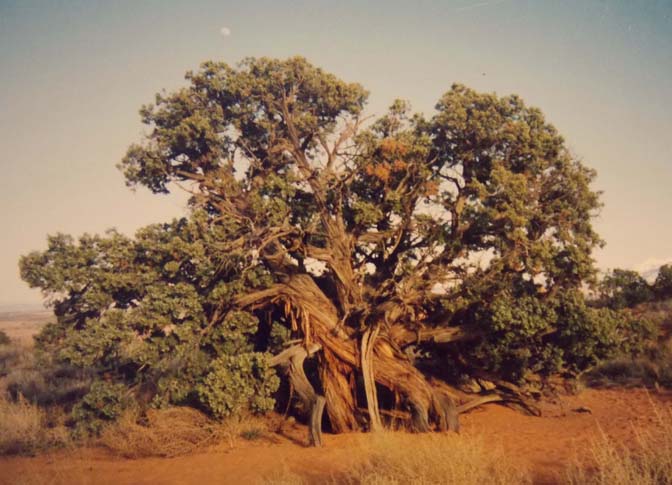

Once I actually carried an old juniper log into my house, but I couldn’t give it to the flames. It sat in my living room until Spring arrived, then I carried it back outside to the wood pile where it still lives. The juniper log comes from the Arizona Strip, one of the least populated areas in the continental United States. Its southern boundary is the Colorado River as it cuts through the Grand Canyon.

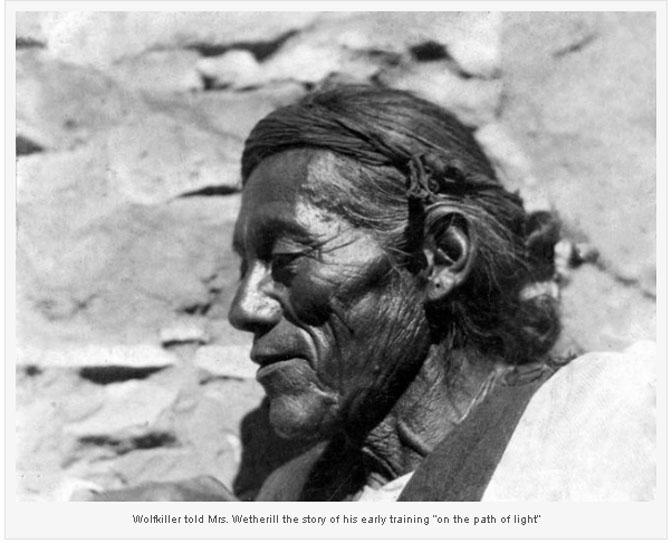

The Arizona Strip—I say the words and I see a land of raw beauty and immense space, a land of myth, a land that stretches the imagination and speaks with voices from the past. How I got there was an accident—or an event or chain of events that were meant to be? Whatever. Once I found my way there, in 1971, and met Ranger John Riffey, I returned again and again.

It was not easy to reach Riffey’s small stone cabin in the Tuweep Valley. Every time that I drove the rutted dirt road that led to Riffey’s, I knew that I was bound for adventure. Arriving at Riffey’s house was like reaching the last lonely house in the last lonely valley. It was the only house in this lonely valley. Never was a light in the window more welcomed. To see that light fed a great hunger. I never knew what adventures awaited me but I knew there was magic at Tuweep and that John Riffey was at the center of it.

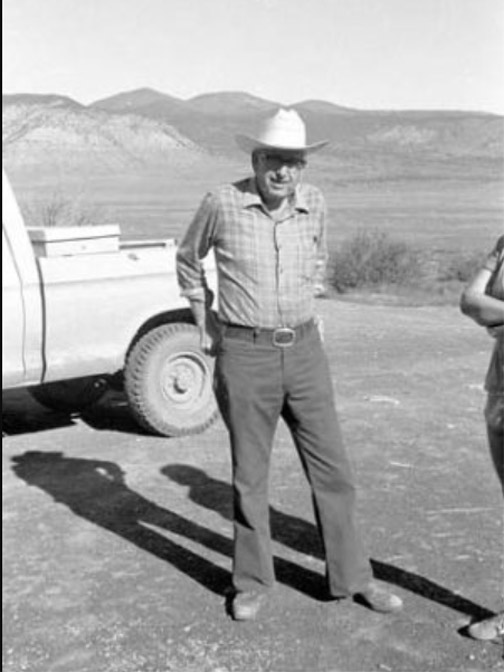

Riffey came to Tuweep in 1942. Came out to spend one night to see if he would like it and ended up staying almost 40 years. “Don’t think that I could have found a better place for me to work and spend a life, “ he once said. “When I retire I’m going to live right down the road; a place good enough to work at is good enough to die at.”

In 1942 Tuweep was part of the Grand Canyon National Monument and Riffey’s main job was working with the ranchers who had grazing permits in the Monument. Over the years the job changed as ranching declined and recreation increased. Later, the Monument became part of the park. Riffey was there for it all.

I remember when John taught me how to drive the road grader. It was November, 1977. The rain had fallen for two days. The third day was clear and Riffey announced to the Park Service crew at breakfast that the conditions were right for grading the road. And that he and I were going to do it. I looked up, my cereal spoon in hand. What? Me, grade the road? But soon we were rumbling along, me behind the wheel of the grader, and Riffey, beside me, giving instructions.

Not only did I learn how to drive Scratchy, John’s name for the grader, and to move dirt from one side of the road to the other, I learned how to tell the difference between a marsh hawk and a red-tail. I learned about winterfat brush and how it once covered the valley before all the grazing occurred. “But it’s returning,” John told me. “After 30 years of controlled grazing, it’s finally returning.”

He told me stories about the ranchers, the Craigs, the Bundys, Old Man White. How they lived, how they worked, and how they died. Stories and more stories, all beneath a bright blue Arizona sky as we slowly rumbled down the road.

We spotted a coyote standing at the side of the road. “Dumb coyote!” John scolded. “Someone is going to shoot him, certain, if he doesn’t pay attention.”

The day before, a coyote hunter had appeared at John’s door, looking for a place to trap. John turned him away from the Park. “It’s crazy, the government pays me to protect the coyote and pays him to kill it. Crazy.”

What a wonderful day it was. On the way home John told me, “You know, there are only three problems with road grading in this country—too much water, not enough water, or just the right amount, and there never is the right amount.” He laughed and I laughed as I tried to keep Scratchy heading straight down the road.

To me, John was the Renaissance Man of the West, familiar with everything in his environment. He knew the calls of the birds and he knew how to fix the small Diesel-generated power plant. He could fly a plane, get a cow out of a cattle guard, fix anything that went wrong, entertain his listeners with stories of the ranchers and the Indians who used to live in the valley. He had a sense of time that was more than minutes and hours. His time included space and a sense of himself in that space.

One Spring, I took my friend Jeff out to Tuweep. I was anxious for him to meet Riffey and to show off the area. We were out at the Rim when I finally asked, “What do you think? Do you like it?”

“Well,” he said, “If it would do for me what it has done for Riffee, I would live here any day.”

I’ve often wondered, does the land change the man, or does the man change the land? Riffey knew the land, loved it, became part of it. He didn’t try to change it, but rather became its caretaker, guardian, interpreter, historian.

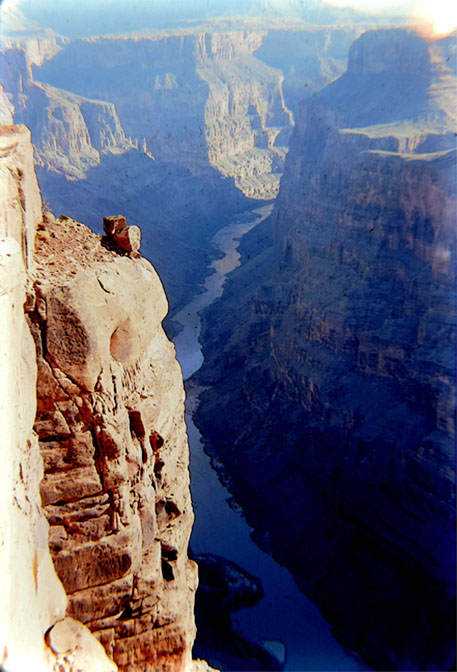

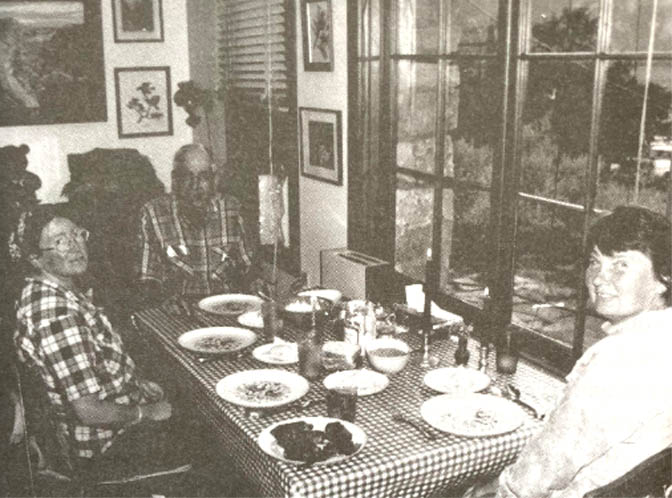

In November, 1978, a group of “granddaughters,” as he liked to call us, gathered at Tuweep to share Thanksgiving dinner with Riffey. It was a wonderful time, filled with stories and laughter, warmth and turkey, fourteen pumpkin pies, trips out to the Rim to look at the river below and to listen to the roar of Lava Falls, three thousand feet below.

Everyone left on Friday, but I decided to stay on for a few more days. Too soon, the time came for me to return home to the Colorado Rockies and winter. I was talking to Riffey about the need to get wood for the coming cold weather.

“I know an area outside the Park where we can get some wood,” he said. “It’s PJ country and it was chained a few years back.”

I looked at John blankly. PJ? PJ meant peanut butter and jelly to me.

“PJ?” I asked.

“Pinion and Juniper,” he explained. And he explained the chaining process to me—two dozers with a couple hundred feet of heavy chain between them, moving through the forest and ripping out every tree in their path. He said they did it to “improve the range.” In spite of the negative results, the practice continues to this day.

We drove Orange Blossom, my truck, to the canyon that had been chained. It looked like a battlefield or as if a tornado had gone through the area. The steep hillside was littered with dead trees, lying on their backs, black arms reaching skyward. A bone yard of dead trees.

John took out his chainsaw and, in no time, the back of my truck was loaded with wood. I gratefully trucked it home to Gold Hill, where I burned it and enjoyed its warmth. And the smell! I love the smell of pinion as it burns. As I watched the flames in the fireplace, I dreamed of my return to Tuweep in the Spring.

Riffey died on the job on July 9,1980. And he is still there guarding the land he loved. The Park Service made an exception to their rules and allowed him to be buried in the Park, just down the road from the stone house that was his home for so many years. I still return to Tuweep. It has become a part of my life. The juniper log remains in my antique pile and probably always will.

Eidie Eilender died on July 18, 2022, twenty-two years and nine days after John Riffey left this world. She died at Boulder, Colorado in an assisted care facility, a place Edie must have loathed. But I’d like to think they’re both enjoying themselves beyond measure, in a place that looks very much like Tuweep. My guess is…that’s exactly where they are.

To read her obituary, click here.

Meeting Ranger Riffey–January 1977: Jim Stiles

The winter of 1976-77 was especially mild and dry, and the dirt road to Toroweap on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, usually snowed in and muddy that time of the year, was open. I figured my new VW Rabbit could go anywhere that a jeep could, so I left the main highway near Pipe Springs and headed south over unknown territory. I’d heard about Ranger John Riffey—the legendary Riffey. And he was already something of a hero to me. I admired the fact that he’d decided to stay at this one lonely outpost for his entire Park Service “career,” if you could call it that. It was his passion, not a job. I wanted to meet him.

We arrived late at the Toroweap Overlook, after dark, and did not realize what a precipitous place we’d selected to camp. Just a few feet from our sleeping bags the earth dropped away, more than three thousand feet to the river below.

“It’s a good thing I don’t walk in my sleep,” I said.

“You do,” replied my friend.

When the sun got high enough to warm us, we broke camp and made the short drive to Riffee’s stone cabin. I walked up to a side door and started to knock. I was sure there’d be no reply. This was January and a cold morning. I hesitated for a moment. I’d also just finished my first season at Arches National Park and I had grown weary of tourists knocking on my door—my residence, as I liked to point out. This ranger home was a bit different, however, and hardly the fish bowl I lived in. So I knocked.

The door swung open and there was Riffey, grinning broadly, as if I were an old friend returning home. He was wearing a red flannel shirt and jeans and slippers, if I recall, and before I could open my mouth he said, “Well! I didn’t hear you drive up. You look like you guys could use a cup of coffee. Corn flakes or Rice Crispies? What suits you this morning?”

A little taken aback by his instant enthusiasm, and wanting to be sure I had the right guy, I asked, “Are you Ranger Riffey?”

He snorted, looked himself over and said with a wink and a smile, “What’s left of him!”

Riffey invited us into his home, brought us coffee and corn flakes and we traded stories for the next several hours. That’s not quite true. It wasn’t a fair trade—he had a lot more stories. Mostly I listened. At some point, I mentioned Edward Abbey’s name and the conversation came to a sudden halt. In 1976, all seasonal rangers loved and adored Ed Abbey and all permanent rangers feared mentioning his name. Being an Abbey Devotee was not a good move for a career ranger then, (probably isn’t now either,) and, for a moment, I thought I’d committed a fatal blunder.

“Do you know Abbey?” Riffey asked sharply.

“Well…,” I hesitated. “Yes…I’ve met him. He lives in Moab.”

Riffey got out of his chair and abruptly left the room. I looked at my friend and shrugged. What should we do? Should we leave?

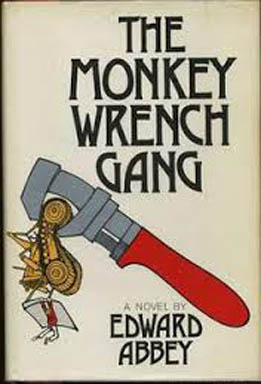

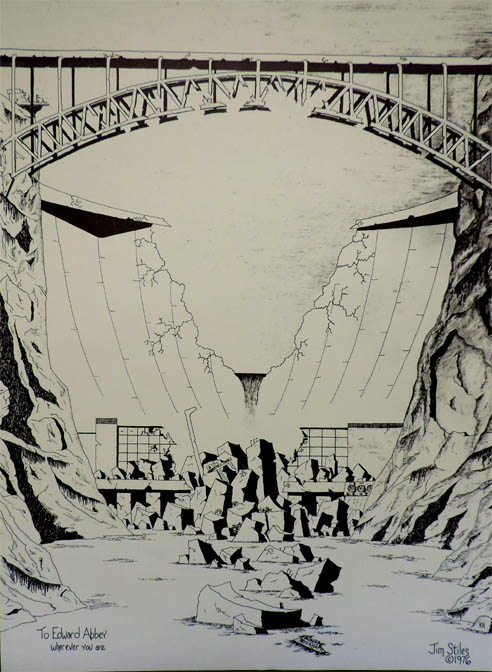

A couple of minutes later, Riffey returned with a well-thumbed, dog-eared copy of a book I instantly recognized. It was The Monkey Wrench Gang. Riffey was now wearing his reading glasses.

“The next time you see Abbey, you tell him that I don’t think this Karo Syrup in the gas tank will do a damn bit of good. I mean about all it’ll do is gum up the fuel filter. That syrup would do a hell of a lot more good on pancakes than pouring down the filler hole on some D9 Cat. Sand! That’s the way to go! And it’s everywhere. Tell him that.”

He was critiquing the book for accuracy.

“And here’s something else…”

It became clear to me that Ranger Riffey was not an ordinary career park ranger. And the longer he talked about his life in the Park Service, the more I realized how true it was.

Except for a brief stint in the Army during World War II, Riffey had spent his entire career at the North Rim, at this isolated outpost. He loved it and he wouldn’t leave, even when the Director of the National Park Service told him he had to.

“Director Wirth…Connie Wirth was just having a fit over me. He wanted me out of there and I don’t even know why. I think he believed I lacked ambition or something. But I got around him.”

According to Riffey, Secretary Udall himself intervened on behalf of the “unmotivated” Tuweep ranger and John never had to worry about transferring again. But he did worry about the 65 mile dirt road that protected his isolation and all the beautiful country that had surrounded him for most of the last 35 years. Rumors were flying that someone wanted to pave it.

“I’ll tell you this,” he said proudly. “I’ll try every trick in the book…the Monkey Wrench Gang book, to keep that asphalt out of here. And it that doesn’t work, they’ll have to pave the road over my dead body.”

He pondered that thought for a moment, and you had the feeling he knew this wonderful life of his couldn’t go on forever. He said, “I know my days are numbered out here. But you know what I’d like? When I die, I wish they’d just stuff me and put me out there in a rocking chair on the porch. And maybe every once in a while, somebody could just give that rocker a push…that would make me very happy.”

We said our goodbyes to John Riffey and promised to come back. Almost a year later, I did return to the stone cabin with a ranger buddy of mine. I was hoping to introduce him to Riffey as well. He was a Riffey Fan as well. But nobody was around, and I assumed Ranger John had taken his days off and gone to “town,’ (the little hamlet — i 1978 —of St. George to get supplies.

Less than two years later he was dead. His friends buried him at Tuweep, illegally and without a permit. The State of Arizona demanded that his body be exhumed, but Merl Stitt, the superintendent of Grand Canyon National Park, said, “No. Leave him where he is.” Stitt was a career NPS man, and usually believed that “a rule is a rule.” But in this case, Stitt’s heart softened. “Just leave him where he is.” It must have made Riffee happy.

NOTE: There is an excellent book about Ranger Riffey, written in 2007 by the daughter of one of John’s “neighbors,” a ranch family that was with him to his last day. The book is called “John H. Riffey, The Last Old-Time Ranger,” by Jean Luttrell. It’s a great read and is still available via Amazon. click here, to read a much more in depth tale of a most remarkable man…JS

TO COMMENT ON THESE STORIES, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THE PAGE. I REALLY WANT YOUR FEEDBACK, EVEN IF IT’S JUST A FEW WORDS…I LIKE TO KNOW YOU ZEPHYR READERS ARE OUT THERE…THANKS—Jim

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

Signed copies

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

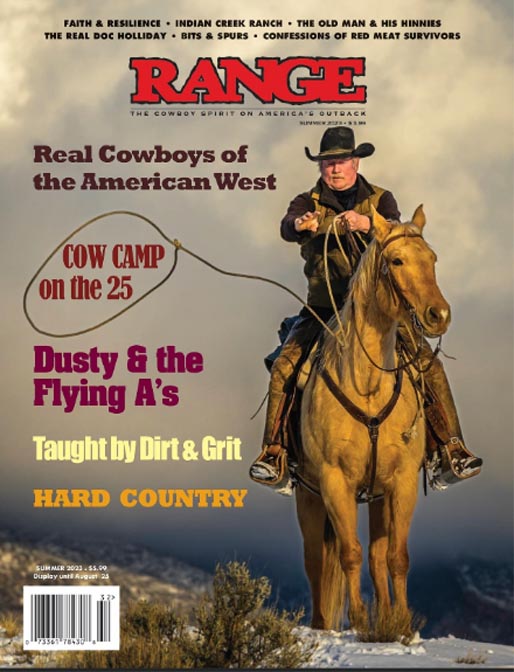

NOTE: The upcoming summer issue of RANGE includes a tribute to lifelong Moabite Karl Tangren.

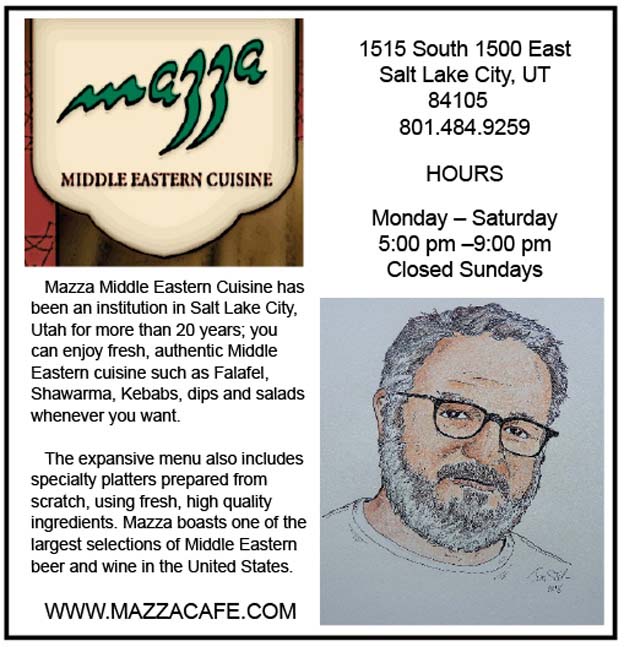

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

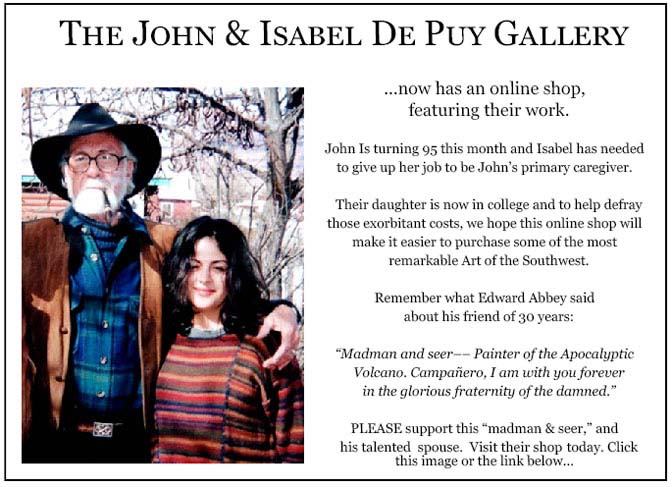

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

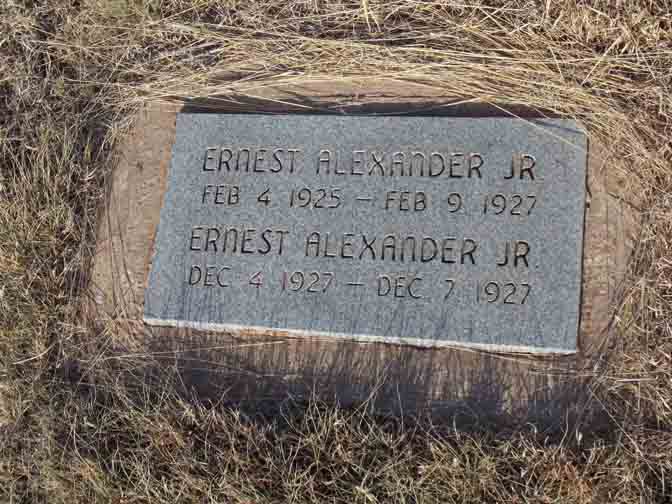

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/05/07/the-heartaches-hardships-that-the-gravestones-tell-jim-stiles-zx-61/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/02/26/glen-canyons-nielsen-ranch-at-hite-the-untold-story-pt-1-jim-stiles-zx51/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/04/02/a-glen-canyon-album-the-nielsen-ranch-at-hite-2-zx56/

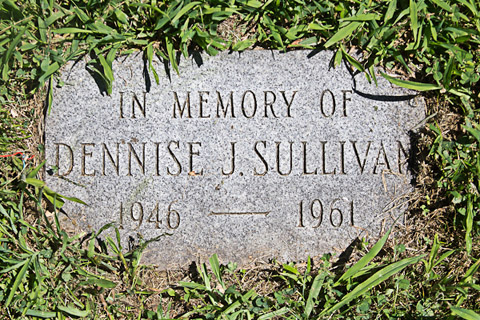

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

PLEASE TAKE THE TIME TO COMMENT BELOW…YOUR COMMENTS AND OBSERVATIONS ARE AS IMPORTANT AS THE STORIES THEMSELVES…OR IF YOU SEE INFORMATION THAT IS INCORRECT…I WANT TO KNOW, SO I CAN MAKE THE CORRECTIONS…THANKS TO ALL OF YOU WHO READ THE ZEPHYR—Jim Stiles

Really enjoyed both your and Edie’s articles about Ranger John Riffee. We did “know” him as in visiting with him each time we camped up there. We even hiked to the river from there and stood on the edge of the campsite looking down on the Colorado River. Riffee was part of the journey. No one quite like him. He was knowledgeable, welcoming–the perfect host we felt. Donna

Thanks Donna…I don’t think there is any place in the West that I have written about or included photographs of, that you and Gail had not already visited yourselves, sometimes way more than a half century ago. What a life you guys have had…

Nice morning read on Memorial Day, as the biscuits and gravy settle in my stomach, dashed and splashed with hot coffee down the gullet.

Riffee is the definition of a Free Ranger, and as I read along, I figured he would show his appreciation for Ed in the way he knew best: with a “here’s a better way to do it, young man.”

Appreciate it, Jim.

Thanks for the two stories. I love reading the intertwined history of the west and the NPS part in preserving it. It’s a complex story yet at it’s root is about the people who lived there and loved it.

So many people dismiss that fact. Thanks.

Sorry about that. I’d been concentrating on her various ways of spelling Tuweep but the most obvious error got past me.

Thanks for the correction. Jim

If that isn’t irony, I don’t know what is…I spelled my own name wrong.

Thanks for publishing Eidie Eilender’s story. I knew her through friends in Gold Hill, a very small mountain town in Boulder County, Colorado. One minor correction, though, Eidie died in the city of Boulder, not in Gold Hill.

NOTE: With great trepidation, I went back into the draft and fixed most but not all of the “Riffey” misspellings…I had pulled another bonehead move the other day in editing the draft of this story, and was fearful if I tried to “fix’ things again, I could only make things worse. Anyway…I tried…JS

Thank you for these two stories (I actually ordered Jean Luttrell’s book about him using your Amazon link)! I’m looking forward to reading the book, once it arrives. (Amazon puts the delivery between June 17 and July 9.)

I’m happy these stories have rekindled interest in Jean’s book. A far better account than what we’ve provided here.

Actually I throughly enjoyed the story and did not even notice an spelling problems.

Thanks Jim great as always. I just ordered the book as well. I do appreciate your effort on the Zephyr.

Thanks!

Perfect. Thanks.

I visited with John in his cabin for hours in the summer of 1975 when I was camping in the campground there (nobody else was there–it was July). He was wonderfully cordial, offered me lunch, and had lots of stories–from the fanciful about Witch Hazel and her Egeroties to the factual: when I asked him why the NPS gave him only a 2wd crew-cab truck, he replied “four wheel drive only gets you stuck in worse places”, and about how engineers were using refrigerant in holes and pipes to freeze the water seeping through the Glen Canyon Damn sandstone abutments so they wouldn’t crumble as quickly (I haven’t been able to confirm this from other sources, but he went into enough detail, I still believe him).

Might have been June instead of July and 1974 instead of 1975 when I was at Tuweep.

I just finished the book. He sounded like an all around great guy who genuinely loved people.

Its much cheaper right now to order the biography from the publisher, Vishnu Temple Press than to use Amazon for it.

John H. Riffey The Last Old-Time Ranger – Jean Luttrell

http://www.vishnutemplepress.com/VTPIndRiffey.html

1975 was my first unplanned adventure in the Arizona Strip and on the road to torroweep..

Erie but fascinating. All alone in a little visited place but evidence of a few but not knowing who.,but feeling a connection. Much like I always feel knowing you are reminding me of our connection because of place and our individualness but unexpected connection because of Place.