PLUS…CHARLIE STEEN COULD THROW A PARTY & FORTY YEARS LATER, WHEN MOAB HONORED CHARLIE—THE “DISCOVERY DAYS” EVENTS OF JULY 4, 1992

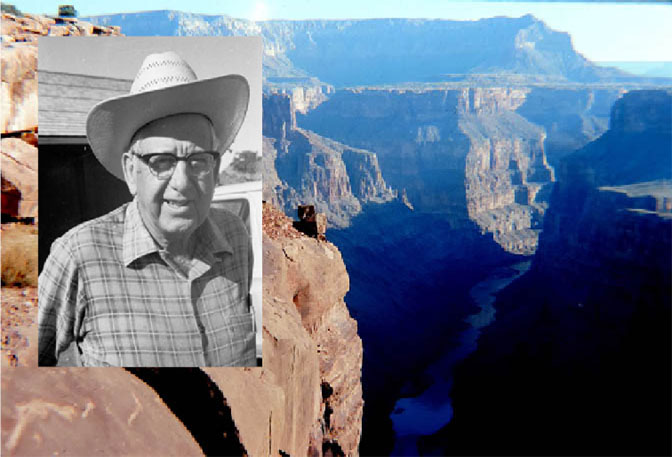

NOTE: If you don’t know who Charlie Steen was, you’ve probably never read this publication, or visited Moab, or heard of uranium. In a nutshell, Charlie Steen was a Texas geologist who had a theory that uranium could be found in a geological formation that had never previously been considered. Almost unanimously, the world of geologists said he was crazy. But Steen and his family carried on; they were down to their last few bucks, when he found exactly what he was looking for, set off a mining boom unprecedented, before or since, in Utah, and made the geologist experts eat crow. For a more detailed profile of Charlie Steen and his life, check out this article at Wikiwand.

Maxine Newell was a story by herself. Soon I hope to repost an interview I conducted with my old friend more than 20 years ago. Maxine was born and raised in Dove Creek, joined the WACS in World War II and saw service in Alaska during the construction of the Alcan Highway, when Americans feared the Japanese might invade the United States via the Aleutian Islands. She lived through the uranium boom, was a reporter for the local Times-Independent and finally went to work at Arches National Park. Though at first she thought I was a damn “Ed Abbey loving hippie,” (which I was), she came to be a dear friend and infected me with her love of history. Maxine passed away in 2015, at the age of 95.

****

Uranium fever became a national affliction when Steen announced his strike. Go-for-broke prospectors poured into the little town of Moab by the thousands, lured by the $100 million bait. The town was besieged by a boom which was to surpass the gold rushes of the previous century.

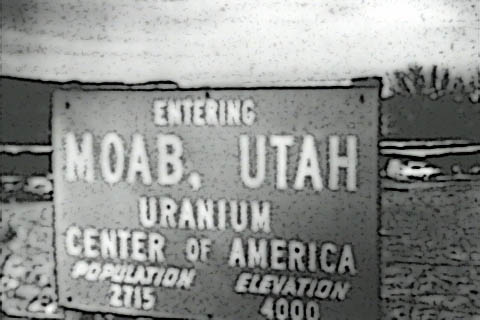

Hopeful investors, loan sharks, and promoters followed the prospectors in. New businesses set up wherever they could find room, on the Main Street drag, in private garages or in tents. One realty firm operated from a tiny log cabin which was the revered historical home of an early-day pioneer. Moab’s new slogan, “Uranium Capitol of the World,” was splashed on store fronts, stationery and souvenirs. The town sported a Uranium Building and a Uranium Days Celebration. The term “uraniumaires” was coined to identify the new mining magnates. Someone finally got around to dubbing Charles A Steen the “Uranium King of the World,” and the title stuck.

Mi Vida fared about as well in the nomenclature. “The Miracle of Mi Vida,” one headline blared. Steen named a street “Mi Vida” in the subdivision he built for UTEX employees, and the Mi Vida mine became known as the “Miracle Square Mile and a Half.”

The boom was a near catastrophe for the little town. Population exploded from 1200 to 7000 in less than a year. There was a shortage of almost everything, and no funds to buy more. There weren’t enough homes, schools, restaurants or motels. Water, sewer and parking were overloaded. Whatever goes into the making of a city, Moab had less than enough during the years it played host to the world’s first uranium boom. To make matters even worse, Mi Vida Mine was located just over the line in the adjacent county. San Juan County collected the taxes; boomtown Moab got the people.

A telephone shortage was part of the boomtown dilemma. Equipped to handle only three long distance calls at a time, Midland Telephone Company was wondering what to do with 1500. It was not unusual to wait days to place a long distance call. More than one busy industrialist found it quicker, and much less frustrating, to drive the 240-mile round trip to Grand Junction to place a call. More frustrated yet were those unfortunates who waited three or four days to place a call only to get a lousy busy signal at the other end of the line. A 3-minute limit was placed on all local calls. Oddly enough, people liked the new regulation. The 3-minute buzzer was a good way to cut off a long-winded caller. When improved equipment allowed the restriction to be lifted, the company was besieged with calls asking that the time limit be retained.

The eventual modernizing of the telephone system is a credit to J.W. Corbin, who had gambled what he didn’t have in the 1920’s to update the family telephone enterprise to its 100-telephone system. But the much bigger investment to enlarge the system to handle the boom load paid off, and the Midland Telephone Company served the town well until, much later, it was sold to CONTEL.

Correcting one problem often complicated another. New subdivisions taxed the overloaded water and sewer systems. New motels added to the overload of the utilities. School was the most discouraging situation. Before the uranium boom, all 12 grades were comfortably taught in one building. As student enrollment skyrocketed, two more schools were built with federal funds, but both were outgrown before they were finished. Triple sessions failed to handle the boom load, even when doubling up on books and seats.

Many transient children were undernourished. Hot school lunches were improvised to see they got at least one good meal a day. School Superintendent Helen M. Knight recalled a constant fear of fire in the old Bell Tower school library where the lunches were served, but the building didn’t burn down until the boom was over.

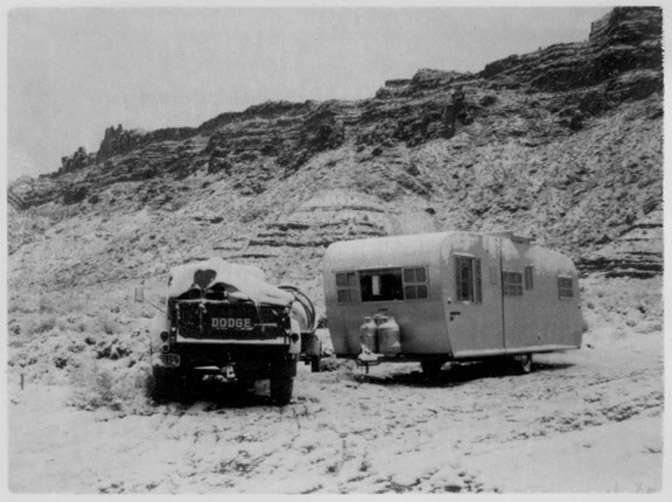

The housing shortage was critical. Many residents took in roomers. The few small trailer parks were filled; trailers were sandwiched in yards and vacant lots from one end of the city to another. A big, new, modern facility, Holiday Haven Trailer Park, was built, but it took the city years to get all the trailer houses legally parked. Prospectors used their cars for home base; used-car dealers all over the country had a run on old school buses for living quarters in Moab. Cardboard shacks lined the ditchbanks, clotheslines stretched from tree to tree up and down Main Street. It is a miracle that the city escaped an epidemic. For a time, it appeared that Steen had lifted the lid off Pandora’s Box and let the troubles out.

It was an exciting boom, nonetheless. If the city had a cartoon appearance, it also had a carnival atmosphere. Nights were filled with partying and laughter. The plush new Town and Country Club was booked to capacity each evening, but no matter where the night of fun began, celebrators ended up at the Uranium Club on the hill, where Utah’s no-liquor-by-the-drink law could be ignored for a $100 membership.

Law enforcement problems were few—people were too busy to make trouble. In the heat of the boom, Swaney Kirby brought his rodeo to town with wild horses, long-horn cattle and brahman bulls that had never been ridden, but there were no cowboys to ride them. The regular bronco busters were all out in the hills, hunting uranium. Swaney loaded up his bad horses, wild cows, and brahma bulls and headed for Texas.

There was standing room only at the two local pubs. Mining deals were consummated over tables in crowded cafes, while hungry customers stood in line waiting for a meal. Geiger counters and ore samples took up so much room on the tables, waitresses had problems finding room for the plates.

The Ides Movie Theater increased its shows to three a night and left a waiting line outside each time the “no room” sign went up. Mrs. Elberta Clark and daughter, Neva Kirk, threatened each night to close it down. A new drive-in theater took off some of the pressure, but in the middle of the boom, Mrs. Clark sold the business that she and her husband had opened when silent “flickers” starred Mary Pickford and Rudolph Valentino, and background music was pumped on a player piano.

The post office added 384 new boxes and it still required a full-time clerk to handle general delivery. They built a new building and outgrew it before it was completed. Postmaster Russell Carter recalled people still pushing mail under the old post office door long after the move. Finally, when annual receipts increased form $8,000 to $80,000 the post office was given first class status, and an Assistant Postmaster, Gene Gibson, was transferred from Helper, Utah to help out at Moab.

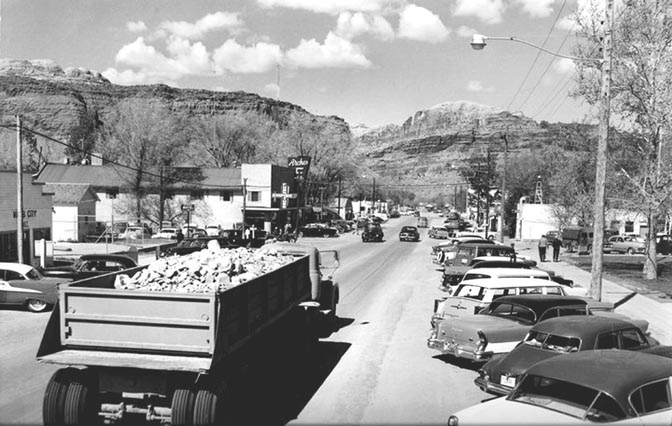

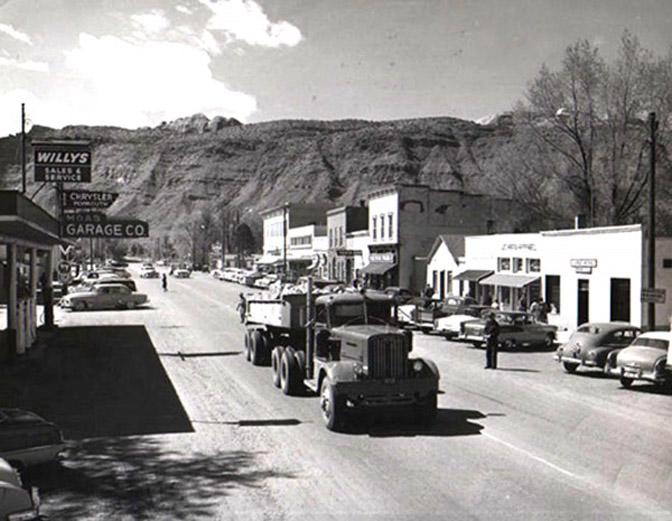

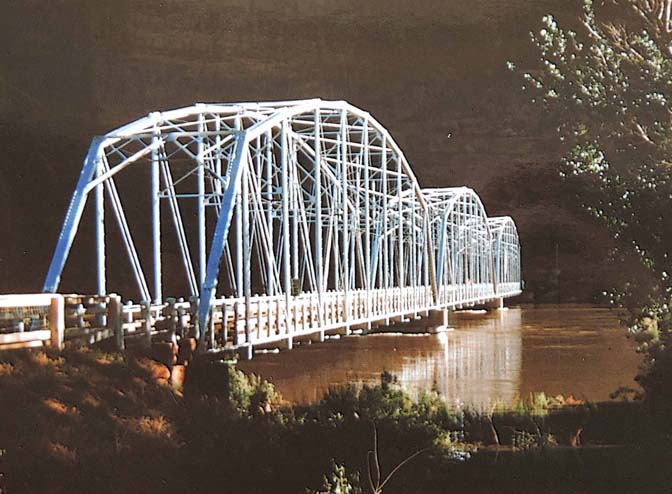

Moab Main Street (U.S. Highway 163) was hard put to handle the car load, let alone the continuous stream of ore trucks enroute to and from the mill, north of Moab, and mine, south of town. One of the most illustrious loads to travel the Main Street highway was the riches single load of uranium in history. The truck load of high grade ore from the Nixon claim in the Lisbon Uranium Company qualified for the Atomic Energy Commission bonus of $10,000, a standing offer since 1948 for the riches load of ore delivered, an effort to encourage more prospectors to hit the uranium trail. The load barely got under the wire before the offer was withdrawn. The government no longer needed an incentive to lure prospectors into the field, and Steen could have topped the record at any given time.

There were no commercial parking lots in town, and curb parking space was filled from morning until night. Business owners complained because customers couldn’t find room to park. The city council attempted to solve the problem by installing parking meters—but that just made everyone mad, so the city took them out.

The most over-wrought person in town was the County Recorder, Esther Somerville. Before the boom, she filled one county record book in about 16 years. She filled one a week during the boom, and then never caught up. When claim location filings reached 4,000 a month, she vowed she’d quit the $3,000 a year job.

The ratio of men to women was 20 to one. A pub owner estimated there were only 50 eligible women in town. Yet Moab was not a typical mining boom town. There were no lewd honky-tonks, no scarlet ladies, and no tin-horn gamblers. The busiest place in town may well have been the new Dairy Freeze.

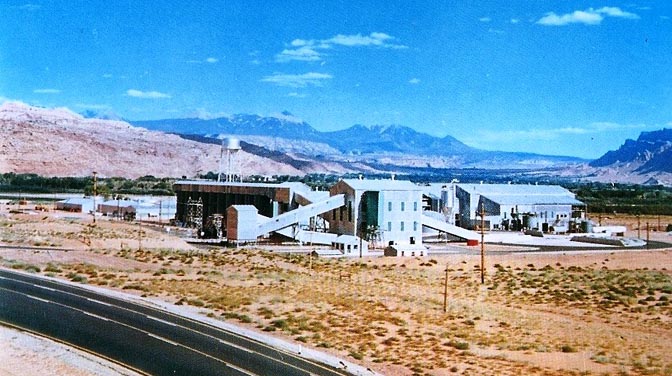

The city was saved by federal funds and officials who knew how to use them: Businessman-Mayor Ken McDougald, City Recorder Darrell Reardon, a dedicated City Council, which often worked the clock around solving problems, and by Charlie Steen himself. Steen did his best to right the upheaval. He built a subdivision for UTEX employees to relieve the housing shortage. Its streets were named after Steen’s family—Juan, Carlos, Marcos and Andrea Courts, (for sons John, Charles, Mark and Andrew;) Rosalie Court, (for his mother;) McCormick Blvd, (for William McCormick, Steen’s UTEX partner,) and Mi Vida Drive. Steen donated land for churches and schools, built a mill, which added a permanent payroll and tax dollars, and built a motel to replace the old “Starbuck” he had remodeled into the UTEX office complex. He took active part in civic affairs, both local and state.

Uranium was a get-rich-quick virus that quickened the gambling pulses of man. Hollywood stars carried Geiger counters to patio parties; Humphrey Bogart, June Allison, and a host of superstars invested heavily in uranium stocks. In New York, a would-be prospector took Charlie Steen’s advice, “Uranium is where you find it,” and staked a claim on the fringe of a military firing range. He started a run on the place, and the National Guard had to be called out to prevent the dude prospectors from being shot.

A hoax started a mad claim-staking spree in the Indian Creek Mining District. Moab Drilling Co. crews detected signs of scavenger probing of their drill holes during weekend recesses, and, as a practical joke they planted some rich uraninite from Mi Vida in the holes. As planned, the mystery probers made their “strike.” The incident set off a midnight claim-staking free-for-all that plagued National Park Service officials years later, when the land became a part of Canyonlands National Park. Superintendent Bates Wilson said endless hours were required to clear the records of defunct claims. No mentionable quantities of ore were ever found.

It was every man for himself during the Moab boom. One armchair prospector hired an amateur surveyor to stake his claims, but with no Surveyor’s Licence at risk to bind his word, the surveyor staked the property in his own name. The boom had its share of swindlers. Ore was planted on ground completely out of the uranium strata and sold to claim-starved lease hounds.

“Where can I stake some claims?” was an introductory greeting when novice prospectors rolled into town. Some took bad advice, and while they pounded their stakes into road rights-of-ways, jokers had their laughs in pubs. City engineers warded off prospectors as they surveyed city streets.

Fortune hunters from all over the nation combined vacations with a chance to strike it rich in Charlie Steen’s country and went on two-week claim-staking sprees in the hills. Their country was so criss-crossed with claims it took years to straighten it all out. The perplexed County Recorder did her best with the thankless job. Professional geologists complained about the amateur hunters; the amateurs stood on their rights.

The country became a lawyer’s paradise. It was predicted that attorneys would wind up uranium millionaires without touching a pick, but most of them didn’t. They too were novices at the game. “Seven Mile Thornberg,” boomtown ID for the Seven Mile Mine owner, hit the nail on the head when he said, “Nobody can tell you what’s wrong with this business, cause nobody knows.”

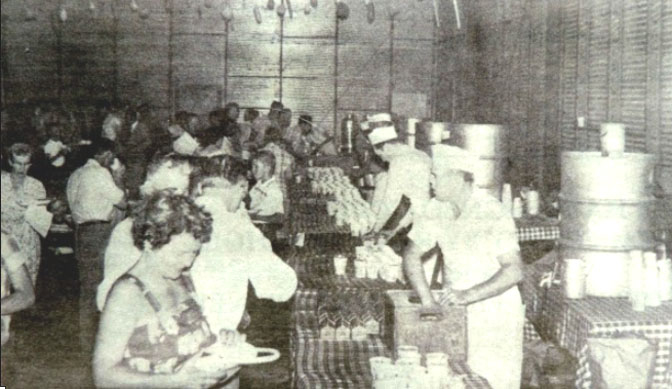

Like the millionaire in the classic play, The Happiest Millionaire, who believed “if I have a million dollars and don’t spend it, I”m as poor as the poorest man in town,” Steen put his money to work. Once a year he contributed to the excitement of the boom by hosting a free-for-all party to celebrate his Mi Vida strike. The largest guest count was 8,884. They came from all over Four-Corners area, for drinks and food served in the old Moab Airport hangar by imported caterers. They came for entertainment by will-known artists, which many of the guests would never have another opportunity to see and hear.

Mostly, however, the guests came so they could say, “I was there, at Charlie Steen’s party!”

CHARLIE STEEN COULD THROW A PARTY—Maxine Newell

The clock on the mantle was set at 5:05, and the bar was always open. Charles relished the role of party-giver, M.L.’s role was hostess. She played it graciously and sometimes enjoyed it. Once, in defiance, she served a buffet of cold cuts to Elliott Roosevelt, E.L. Cord, and Joseph Frazer (Wall Street financiers and automobile manufacturing executives.) They declared it the best meal they’d had in years. The tycoons may have felt they received better treatment from M.L. than from Charlie; they offered him $10 million for Mi Vida and were turned down flat.

Hilarious incidents happened so close together at Steen Hill, some are hard to recall. At one party, Betty Bowen, a pretty lass from Texas, disrupted the festivities to salute her fellow Texan. She confiscated the two bands hired for the occasion, arranged them with the guests around the pool, then took a precarious position on the end of the diving board to lead them in song, “The Eyes of Texas…” Charles led the cheers.

Steen Hill parties were lavish; guests often numbered in the hundreds. Expense was no object. Famous caterers were flown in for major events. Noted entertainers were brought in. Champagne flowed freely; guests danced the Tango and the Cha Cha. A Salt Lake City club owner “walked on water;” (someone was always getting dunked in the pool.” Entire filming casts cavorted. Susanne Paulson, Miss Utah of that era, signed the guest register. Joe Fitzpatrick of Walker Bank distributed harmless methylene blue pills “for hangovers” and created a bathroom panic.

WELCOME BACK CHARLIE STEEN — “DISCOVERY DAYS” July 4, 1992 — Jim Stiles

In the Spring of 1992, I was starting The Zephyr’s fourth year. Earlier that winter I had met and been befriended by author Robert Fulghum and his wife. Fulghum had written the best seller “Everything I Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten,” and had made Moab his new home. One day, we were talking about the dramatic changes Moab was experiencing—-Industrial Tourism was already in its early stages — and I mentioned the Uranium Boom of the 1950s. Though I wasn’t here for it either, I knew its history and especially the saga of Charlie Steen.

Fulghum was intrigued. July 4, I told him, marked the 40th anniversary of his discovery. Fulghum wondered if there were any plans to mark the occasion. It was a good question and the next day, I paid City Councilman Dave Sakrison a visit. I asked if he thought the City of Moab might want to sponsor a celebration of Charlie Steen’s discovery. Sakrison loved the idea and took it to the Council and Mayor Tom Stocks. The vote was unanimous.

July 4,1992 would be “Charlie Steen Discovery Days.” The project took on a life of its own. A planned dinner at the Elks Club was a great success. Friends and employees from decades past heard about the event and traveled hundreds or even thousands of miles to honor Charlie. The large room at the Elks was packed. A film copy of a television movie about Charlie, played by actor Jackie Cooper, was shown on an old 16 mm sound projector. And after a number of speeches honoring the man, Charlie stood humbly to the thunderous applause and cheers of these hundreds of men and women whose lives he had touched. Charlie was so overwhelmed he could barely speak.

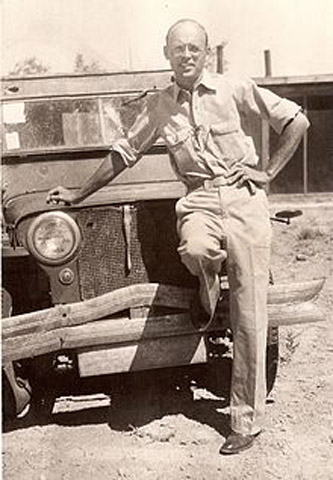

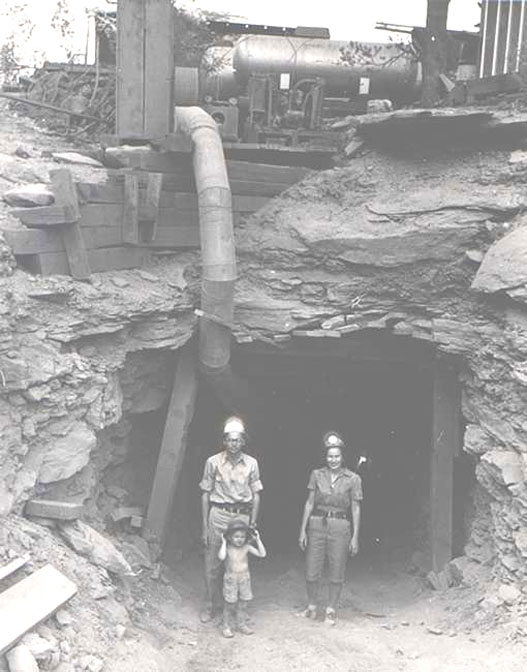

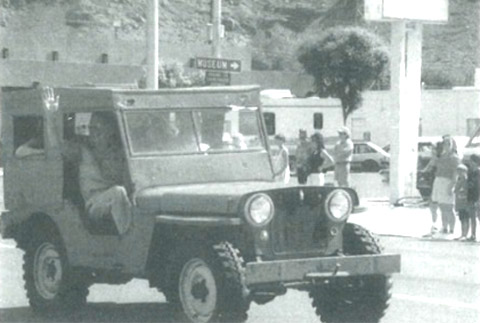

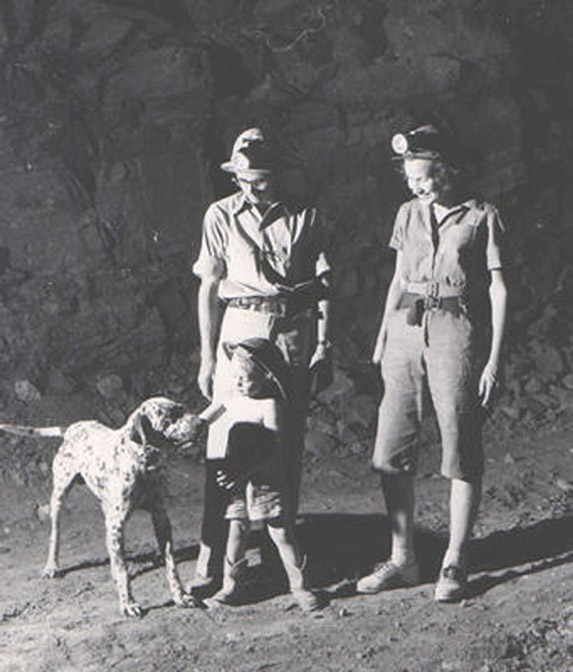

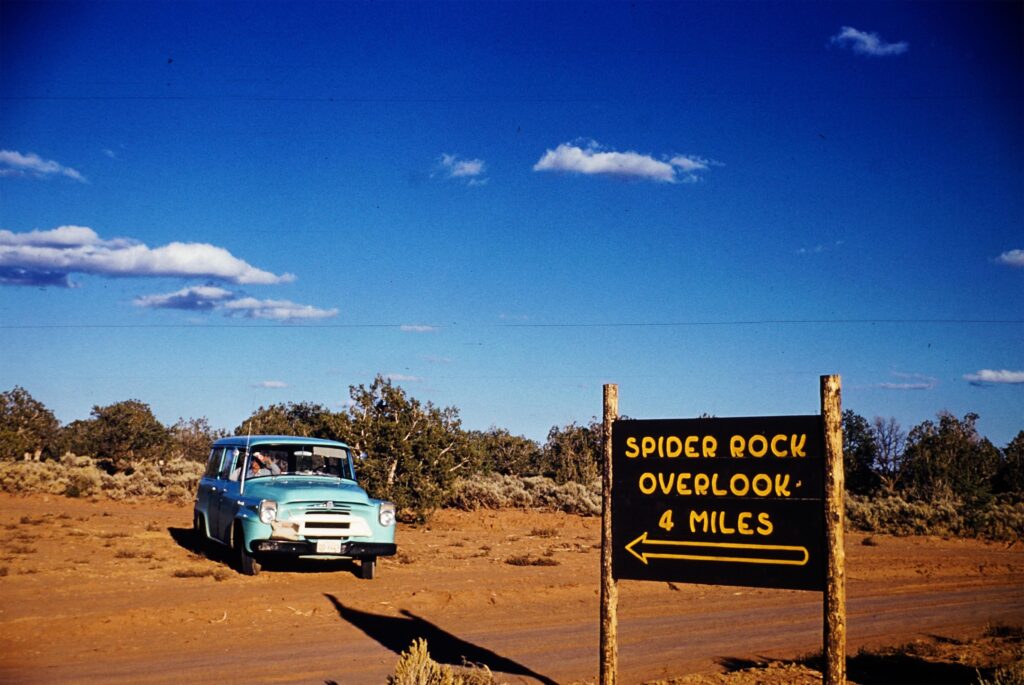

PREFACE: The next day, one of Moab’s biggest parades closed traffic on Main Street. Charlie was the Grand Marshall and incredibly, he rode in the very Jeep he had owned in 1952 when he made his find. Later the City Park served as a venue for a picnic, attended by hundreds. And finally, the Steens and a large group of friends paid a visit to Big Indian mine. Charlie hadn’t seen it in years, and this would be his last.

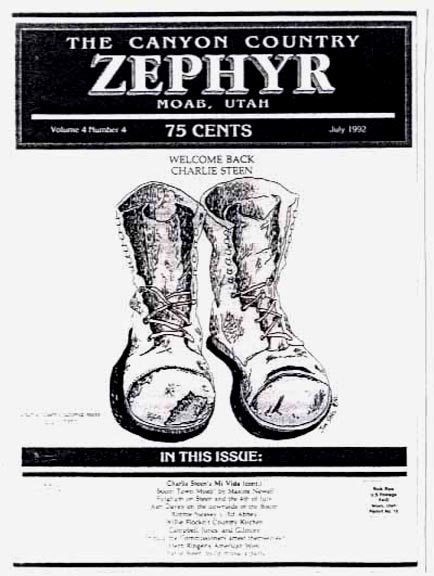

On July 1 , I printed the July 1992 issue of The Zephyr—the cover featured Charlie’s old work boots — the ones he was wearing on the day his life changed forever (The boots were later bronzed). Below is my “Page Two” story announcing the “Discovery Days” celebration….

From the July 1992 Zephyr:

Moab welcomes back Charlie Steen this month and pays a long overdue tribute to one of the most colorful and unique characters that our town can or ever will remember. I think I’ve heard Charlie Steen stories since the week I arrived here, more than 15 years ago, and I’m looking forward to meeting the man behind all those stories.

Some people have questioned why a newspaper that has been labeled in some quarters as a “radical, environmentalist rag” would have the slightest interest in commemorating the exploits of a uranium miner. It is true that parts of southeast Utah still show the environmental effects of the uranium boom, and the health effects of exposure to radon gas is a tragic and well-documented fact. But it was a different time and world. In the Cold War, men like Steen and his workers felt, if anything, proud of their work. They considered themselves Patriots. And they were.

But this is also about Charlie Steen, the man. It is a story about unshakable dreams, and about courage and perseverance. As Robert Frost once wrote, it’s about “the road less traveled.” And it may be the last time in human history that one man with a dream could pursue it alone. Today, giant corporations with millions of dollars of equipment and technologies unheard of just a few short years ago, lay claim to vast amounts of land in pursuit of maximized profits or at least a good tax write-off.

But it’s a sterile, de-humanized effort that lacks the soul of those Boom Years in Moab. It was the last of an innocent age. While many regard the late Ed Abbey as the last man in the world to have a kind word to say for the uranium miners, listen to what Ed wrote in his classic book Desert Solitaire…

“After a visit to Miller’s Supermarket, I am free to visit the beer joints. All of them are busy, crowded with prospectors, miners, geologists, cowboys, truck drivers and sheepherders, and the talk is loud, vigorous, blue with blasphemy. Although differences of opinion are known to occur, open violence is rare, for these men treat each other with courtesy and respect. The general atmosphere is free and friendly, quite unlike the sad and sour gloom of most bars I have known.”

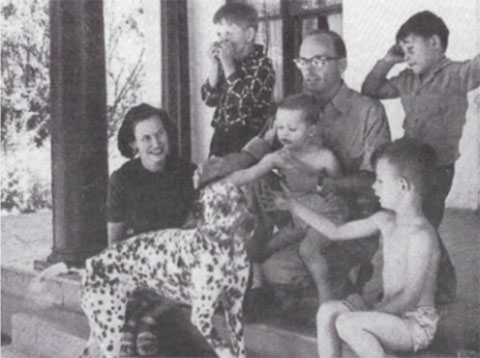

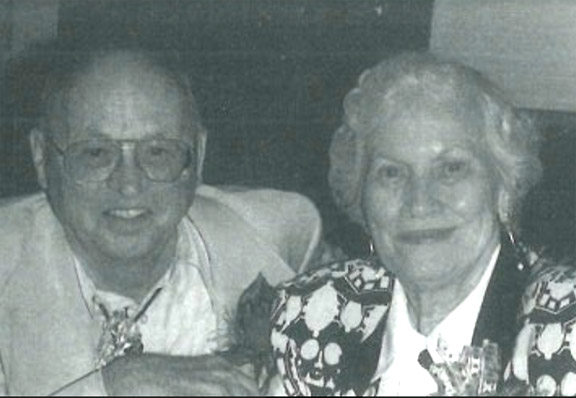

This is also a great love story. Quite simply, Charlie Steen would never have been able to pursue his dream without the love and encouragement and faith of his wife, M.L. As Charlie said in Maxine Newell’s recently published book on his life, “M.L. was different…she was the whole difference.” She and their boys endured incredible hardships and sacrifices while Charlie searched for his elusive uranium. But she never doubted him or stopped believing. She once wrote a friend, “If we never have money, I’m rich with him.” Their faith and love in each other endures to this day.

Charlie Steen was happiest when he was with the prospectors that followed him to Utah. He was no financier and when that role fell to Charlie, his troubles began. He once told a writer for FORTUNE magazine that he regretted not stashing his wealth in a Swiss bank account. Among his more unfortunate investments was a Nevada cattle ranch which lost a million dollars when the price of beef plummeted. He traded part of the ranch for an orange grove in California. Bad weather wiped out the grove and any hope of a profit. And he invested $100,000 in a Yugoslav-style gourmet pickle company. According to Charlie, “They were good pickles,” but an early frost destroyed the cucumber crop two years in a row.

There will never be another time that can match the feeling of the Uranium Boom. The glory of those times is tempered by the knowledge that lives would be lost to uranium exposure-related illnesses. But to look at the 50s in the context of the times, that dark cloud hung silently in the future…no one knew it was there, and so it never dampened the spirits of the participants at the time.

Charlie’s colorful legacy will be remembered this month in a series of events, beginning on July 3. Welcome home,…..Jim Stiles

AND FINALLY…TO READ THE BEST ACCOUNT OF CHARLIE STEEN’S DISCOVERY, AND THE BOOM THAT FOLLOWED, HIS SON MARK WROTE A FOUR PART SERIES FOR THE ZEPHYR CALLED “MY OLD MAN…THE URANIUM KING.”

CLICK THESE HOT LINKS TO ACCESS THEM: PART 1 PART 2 PART 3 PART 4

TO COMMENT ON THESE STORIES, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. I’D ESPECIALLY LOVE TO HEAR FROM PEOPLE WHO KNEW AND WORKED WITH CHARLIE STEEN & LIVED IN MOAB DURING THE 1950s.

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

NOTE: The summer issue of RANGE includes a tribute to lifelong Moabite Karl Tangren.

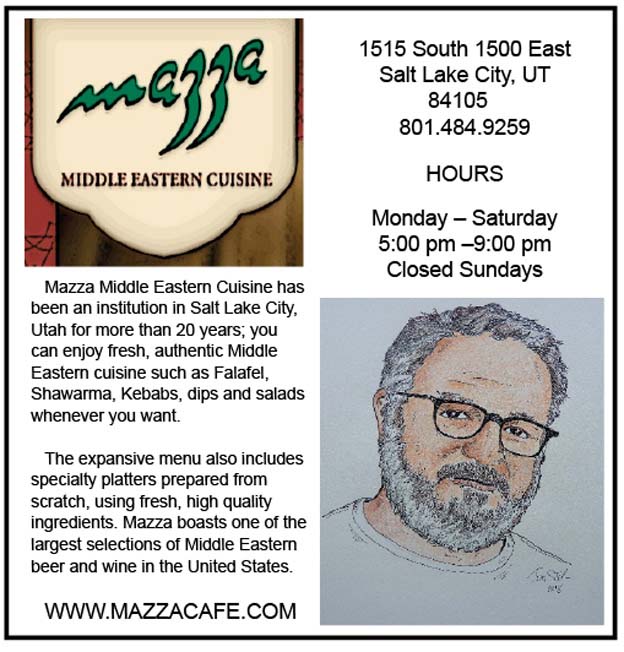

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

Adios Amigo…

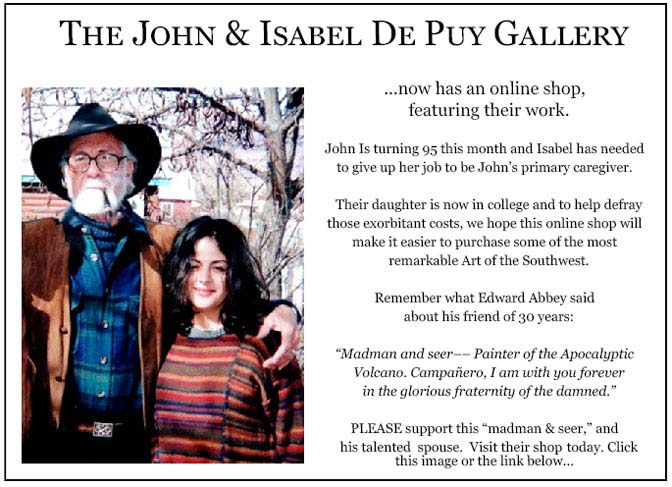

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/04/23/1957-aerial-views-of-arches-national-monument-before-the-asphalt-zx59/

PLEASE TAKE THE TIME TO COMMENT BELOW…YOUR COMMENTS AND OBSERVATIONS ARE AS IMPORTANT AS THE STORIES THEMSELVES…OR IF YOU SEE INFORMATION THAT IS INCORRECT…I WANT TO KNOW, SO I CAN MAKE THE CORRECTIONS…THANKS TO ALL OF YOU WHO READ THE ZEPHYR—Jim Stiles

How many employees of these “uraniumaires”died with some form of cancer, Jim? Do you have the numbers to hand?

Did they even know the risks involved with mining uranium?

Hey, this worked!! I forward these bits of history often because they’re so well recorded! I think Lithium is the newest mineral set to start another bunch of searchers. Glad you continue to unearth so many good stories!!

During the Steen era, my father was involved in uranium mining throughout the region, from Nucla to Uravan to Yellowcat, and some claims in the La Sal mountains that he owned with a friend. We moved to Moab during the winding down of Charlie Steen’s Uranium Boom. In 1964 Pappy got a job at the Texas Gulf potash mine, and mineral stakes had become diversified. Steen was the iconic local guy and Moab’s mystique at that time had everything to do with his career and personality. As famous as Charlie Steen was, I don’t remember anyone ever speaking ill of him or his family.

With all of Steens work and the uranium industry, plus the incredible story of the potash mine and disaster in the 1960’s, it would seem appropriate for Moab to do something to honor their mining legacy and Steen. Some downtown art or plaques could help people remember that it was really mining that put Moab on the map.

I received this comment from an old associate of Charlie Steen, but who no longer has the faculties to navigate the complexities of the internet…Here are his comments:JS

Responding to Bob London’s question about how many employees of “uraniumaires” died of some form of cancer, and if the miners even knew the risks involved mining uranium, I can say that most of the miners who worked at the highly mechanized Mi Vida and Big Buck mines lived for many decades after producing about 24,000,000 pounds of uranium oxide from very high grade uraninite ore. Contrary to the modern popular myth that mining uranium in the 1950-1982 period was a certain death sentence, thousands of miners did not contract cancer from their decades of working underground.

This is what the passage of time has done to the history of the 1950s Uranium Boom, and it seems to have become the popular, abbreviated account of this era. Here is what actually happened: By the end of 1946 there were only a total of 55 men employed in 15 uranium-vanadium mines operating on the entire Colorado Plateau. It was from this almost nonexistent resource base that the Atomic Energy Commission launched its Domestic Uranium Procurement Program in 1947.

After the AEC announced the 10-year incentive program, very few amateur prospectors swarmed over this part of the Colorado Plateau. Most of the men who were searching for uranium were old time prospectors and professional mining people associated with small vanadium mining companies that were now incentivized to search for uranium in the same Morrison Formation where they had been mining vanadium during the war years. These professional mining men had fairly good success discovering more uranium in the Salt Wash Member of the Morrison Formation in the Uravan Mineral Belt and in the Shinarump Member of the Chinle Formation in the White Canyon mining district. These smaller Salt Wash and Shinarump ore deposits were mostly discovered because they were outcropping, but there were so few roads in those days that only a small number of them had been located and placed into production before the AEC announced the incentive program in 1948.

By 1951, there were over 150 small mines in operation, but only a few were producing 50 tons per day. Most of these were located in the Uravan Mineral Belt or the Temple Mountain District. A few others were shipping ore from the Yellow Cat area, and the Happy Jack Mine in the White Canyon District was just starting to look like a promising source of uranium for the Atomic Weapons Program.

Everything changed on July 6, 1952 when the Mi Vida mine was discovered by Charles A. Steen. Prior to the discovery of the Mi Vida ore deposit on July 6, 1952, most of the uranium mines were small mining operations. If there were no high-grade uranium ore deposits located on the Lisbon Valley Anticline, there would never have been the Uranium Boom that actually brought tens of thousands of amateur prospectors and get-rich-quick hopefuls to this area. After Charlie Steen’s discovery became widely publicized in the newspapers and popular monthly publications like True and Argosy Magazine, the Uranium Boom really became a rush for riches. More than 300,000 uranium mining claims were staked in Utah in the four years after my father’s highly publicized discovery encouraged people to try and find a fortune in uranium. Most of them didn’t make a fortune, but a lot of them never left this area, and very few of them ever regretted taking part in this first Uranium Boom. These were some of the same people who opened up most of the territory that is now visited and enjoyed by several million people every year.

In fact, the discovery of the Big Indian Ore Belt’s million ton, high-grade uraninite ore deposits is what brought large mining companies into the uranium exploration and mining business, and they changed the way that uranium deposits were discovered and exploited. All of these big mines were very well ventilated, while the smaller mines were not ventilated at all times, because it cost money to run the diesel compressors that brought fresh air inside the uranium mines. The U.S. Bureau of Mines and the AEC regularly inspected all of the mines to insure that they were properly ventilated, and not smoking underground was discouraged and later strictly enforced. However, most of the small mine owners and operators were making a good living, not becoming millionaires selling uranium ore to the AEC, and most of the miners addicted to nicotine disregarded the ban on smoking underground and they later paid the price for their habit.

Thanks Jim!