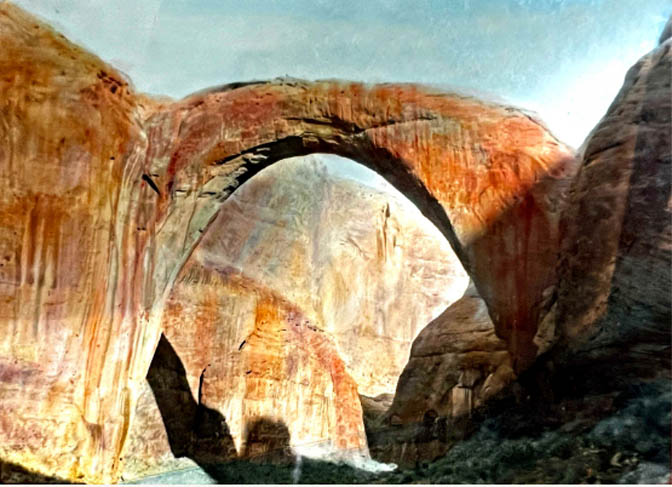

The Navajo Mountains and the Natural Bridge were, to me, terrible. I can never give you a complete description of it, but, aside from the other difficulties and trials, it impressed one as the most godless place conceivable. I don’t see how anyone can keep any religion in the canyon in which the bridge is—such a mass of turbulent, ruthless rock, all dark red—hopeless, shapeless chaos.

— Elena Feodorovna “Nelka” de Smirnoff, 1910

Despite her remarkable fortitude in the face of previous ordeals and hardships, 32-year-old Nelka de Smirnoff nearly reached her limit during her 1910 horseback ride to Rainbow Natural Bridge. The daughter of Count Theodor de Smirnoff, a Russian nobleman, and Nellie Blow, a wealthy St. Louis socialite, she had experienced the best of both American and European culture while growing up. When she was 25, she volunteered to serve with the French Red Cross as a nurse to soldiers wounded in the war between Russia and Japan. A year later she joined the Russian Red Cross and dealt with the horrific effects of war to the injured men she treated. But the stamina she gained through those trying situations was barely sufficient for the challenges that confronted her on the Rainbow Bridge trail.

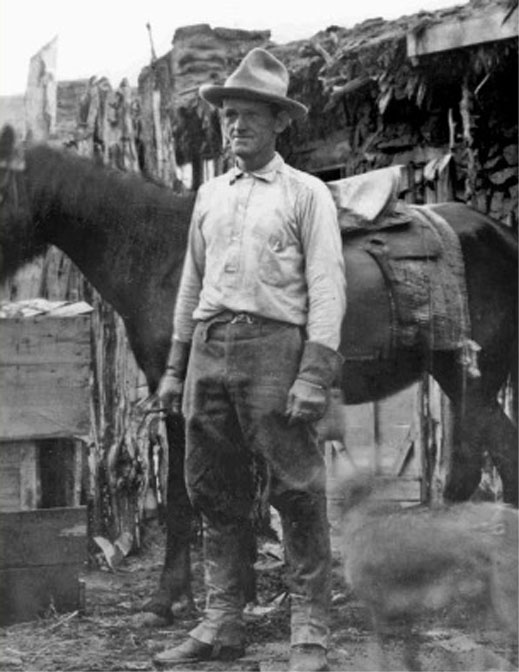

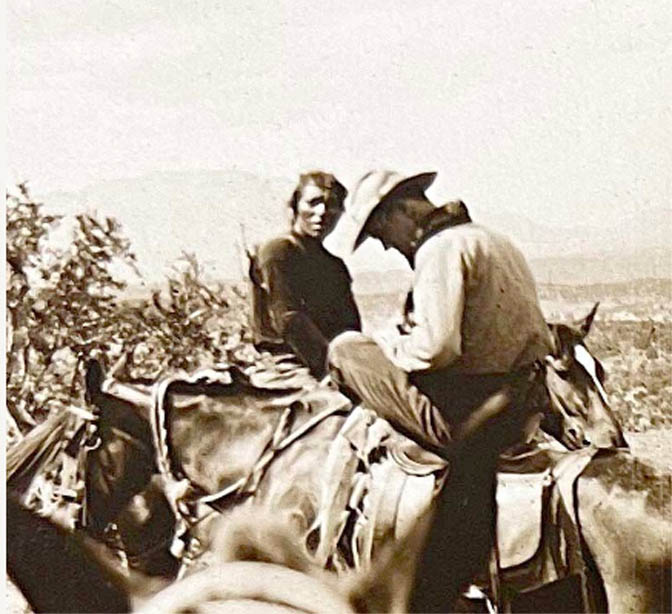

Nelka learned her horse-riding skills from her accomplished aunt, Martha Blow Wadsworth, who accompanied her on the expedition. Martha was 45-years-old at the time of the trip. Also along were Lieut. Nathan C. Shiverick of the 3rd Cavalry, Rock Island Arsenal (age 27); Reginald S. Huidekoper (age 34), who was Assistant United States Attorney and an officer in the Chevy Chase Hunt Club; three packers; a cook; and their guide, my great-grandfather, John Wetherill of Oljato, Utah (age 44).

The existence of the massive Rainbow Natural Bridge, located deep in the canyon country of southern Utah, was unknown to the public until 1909. In August of that year, a group of expeditioners, guided by Native Americans and John Wetherill, undertook a long, tortuous horseback journey to reach it. They were duly impressed with its grandeur and promptly spread the news of its remarkable size and beauty. (For more on the 1909 expedition, see my article, “Finding Value in Hardships,” in the April/May 2021 Canyon Country Zephyr.) Based on their reports, President Taft designated the area as Rainbow Bridge National Monument in May of 1910. In August of that year, Nelka and her compatriots came out West to see it for themselves.

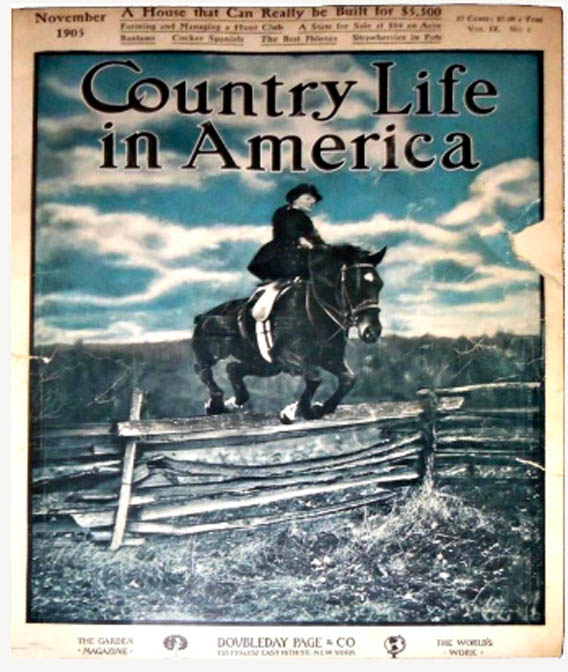

Martha was married to Herbert Wadsworth, a millionaire gentleman farmer. They had mansions in Avon, New York, and on Dupont Circle in Washington, D. C. The couple rubbed elbows with the East Coast elite, including the Theodore Roosevelt family. In addition to her social activities, Martha’s favorite pastime was riding her horses. The November 1905 issue of Country Life in America magazine featured a photo on the cover of her on her horse, jumping over a high fence. In January of 1909, Roosevelt had challenged his army and officers by riding 98 miles in seventeen hours. In June 1910, Martha beat the President’s record by riding sidesaddle, using a relay of horses, and covering 212 miles in just over twenty hours.

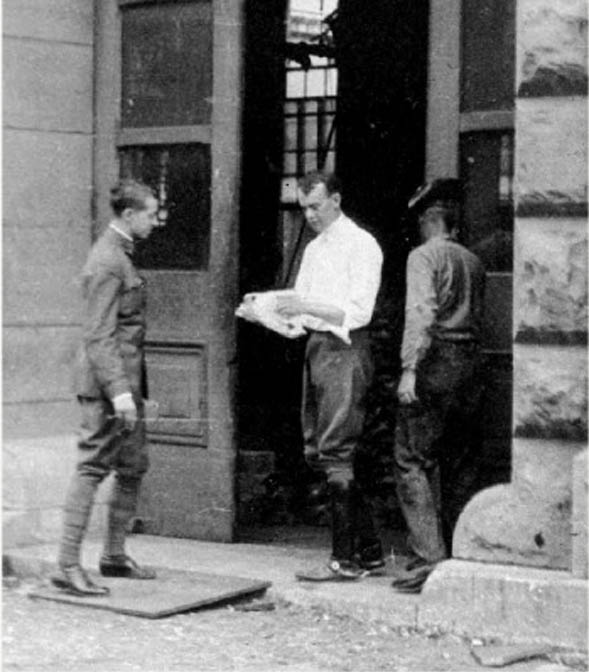

General Robert Shaw Oliver, then Secretary of War, shared Martha’s love of horses, and the two became personal friends. Gen. Oliver was planning a reconnaissance trip through New Mexico and Arizona, and he invited Mrs. Wadsworth to join him. She, in turn, asked her niece, Nelka, to come along. The General also invited Lieut. Shiverick, who had invented compressed blocks of horse food and was interested in testing them out on the trail. Since Rainbow Bridge was not on Gen. Oliver’s itinerary, Mrs. Wadsworth and her party would accompany him on the first part of his excursion, then head off on their own.

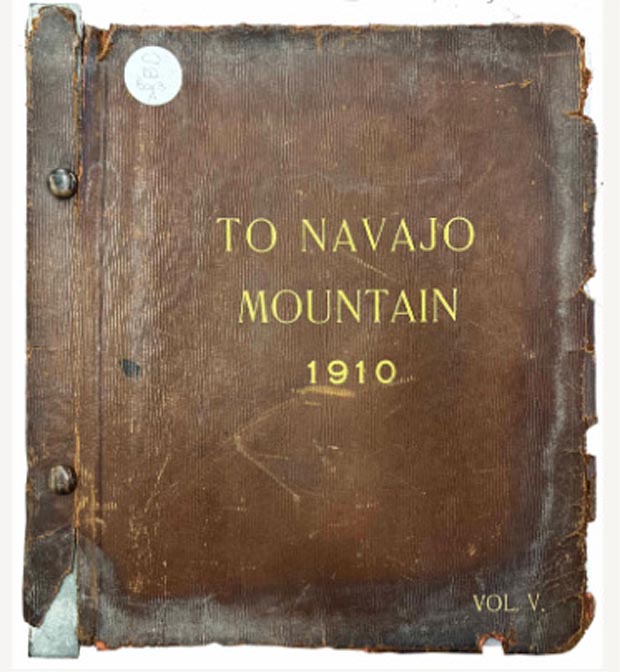

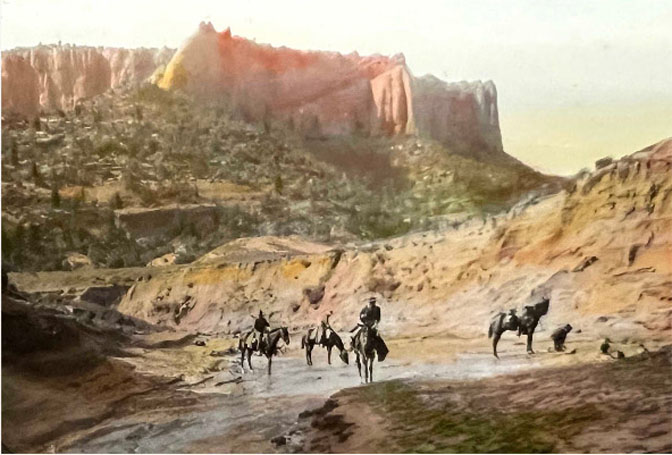

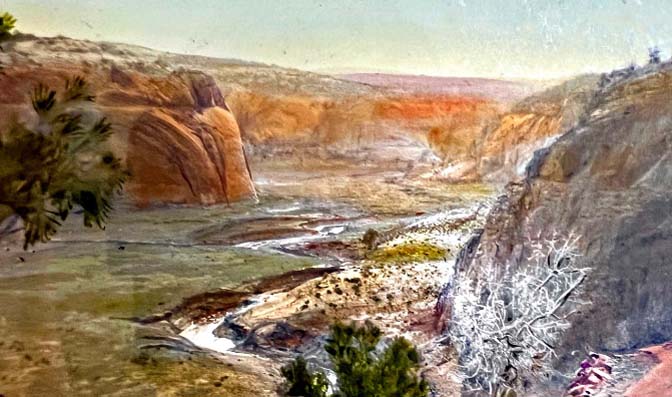

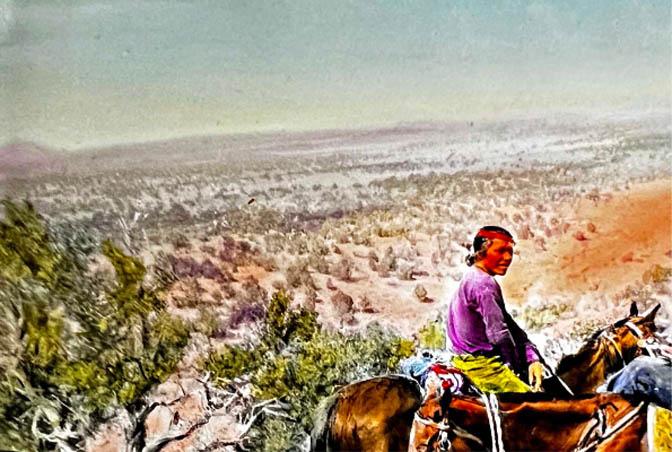

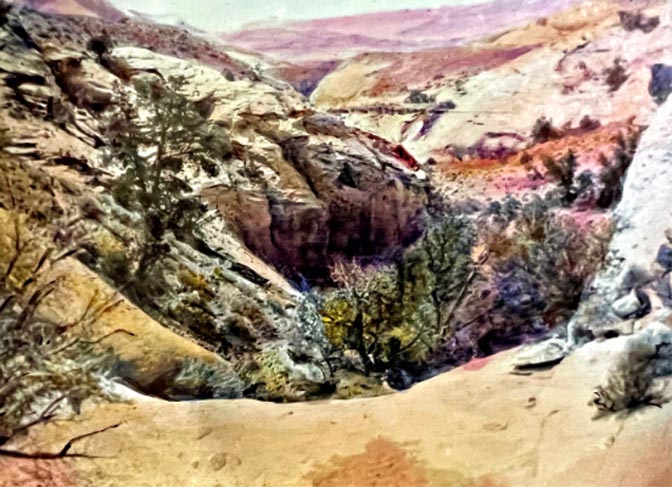

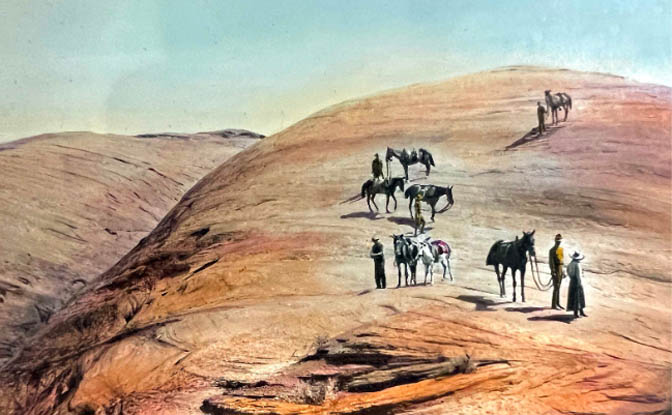

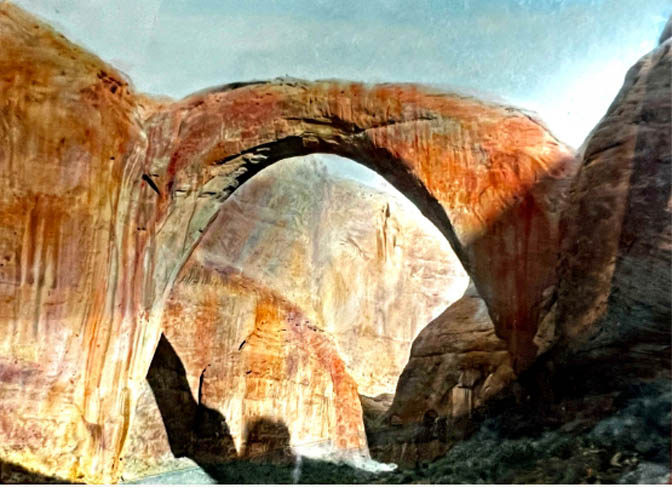

Besides sharing her skills at long-distance horse riding, Martha contributed significantly to the expedition by recording hundreds of scenes along the way with her camera and later organizing the photographs into six large albums. She also selected more than 100 of her images to have replicated as hand-colored lantern slides for her family members and friends back home to see. Her photo albums and glass slides are preserved in the Martha Blow Wadsworth Collection, Special Collections Department at the State University of New York (SUNY), Geneseo Fraser Hall Library, who kindly made them available for reproduction in this article.

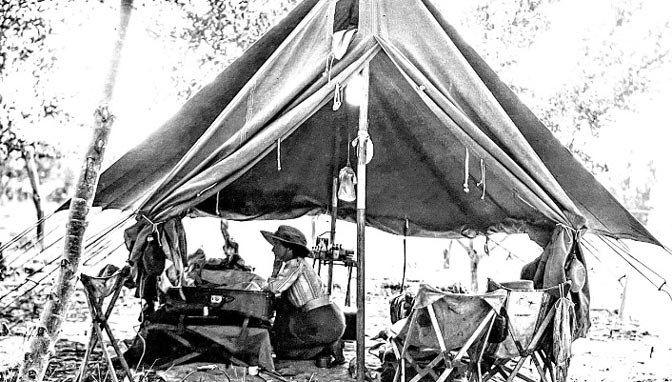

with one of his blocks of compressed horse fodder. (MBW Collection.)

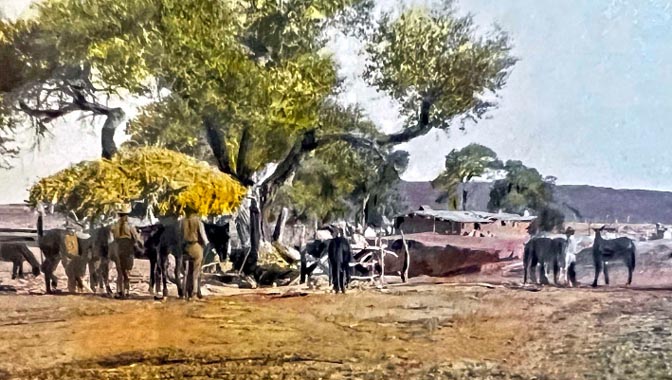

The entourage traveled by train to Fort Wingate, New Mexico, where they arrived on August 1 and were greeted with military pomp by Troop I of the 3rd U. S. Cavalry. Then they headed west on horseback in relative comfort, accompanied by the cavalry troop, a few dozen pack mules, and military-style camping amenities.

The expedition passed through Gallup, New Mexico, then on into Arizona, where they visited Fort Defiance on the Navajo Reservation, Canyon de Chelly, Ganado, the Hopi mesas, and Tuba City. The easterners had their first encounters with Indigenous communities, and Nelka found something to admire in the native lifestyle. “Every place where the Indians live in their natural mud huts it is clean and inoffensive,” she wrote.

At Tuba City, the Rainbow Bridge group parted ways with Gen. Oliver’s troop and headed northeasterly across the desert on their own. Their camping supplies were now more basic, and they would be self-reliant from then on.

Martha’s photos and lantern slides, with her associated captions, provide a detailed record of the group’s route and itinerary. Nelka’s reports of her adventures and misadventures in letters she wrote to her Aunt Susan Blow document some of the incidents along the way. (Excerpts from her letters are quoted in her biography, Nelka: Mrs. Helen de Smirnoff Moukhanoff, 1878–1963, a Biographical Sketch, by Michael Moukhanoff.)

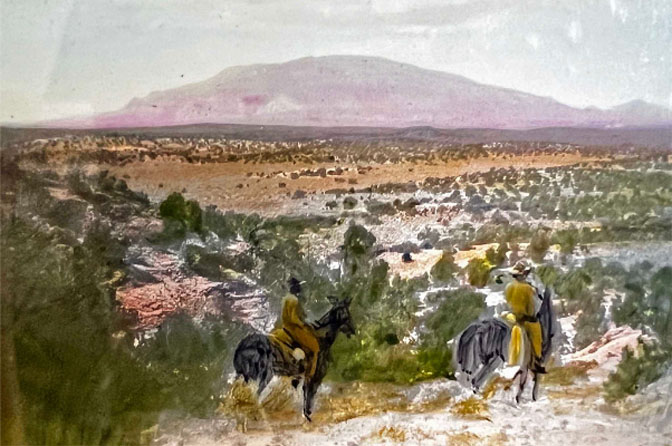

Their first sixty miles beyond Tuba City went through country now traversed by Highway 160, which passes the Red Lake Trading Post, Red Lake, a rock formation known as the Elephant’s Feet, and on to the rugged Marsh Pass at the mouth of Tsegi Canyon. From there, the team entered the canyon bottom and followed it upstream.

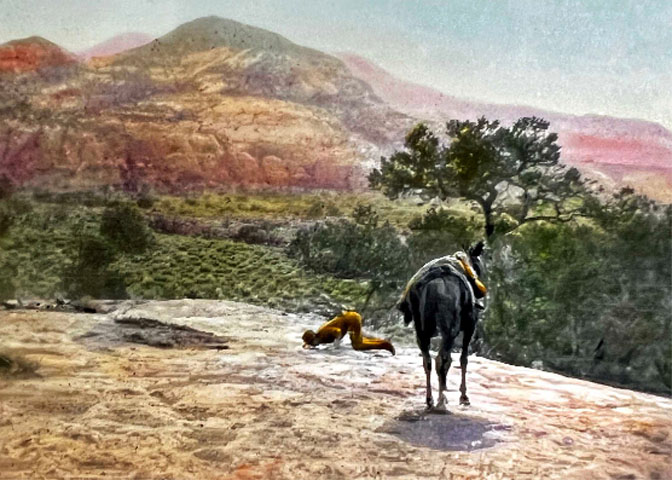

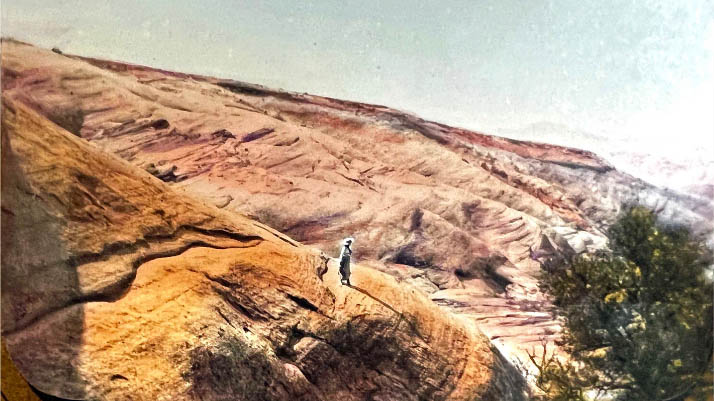

Wadsworth’s hand-colored lantern slides in the MBW Collection.

Captions in quotation marks are hers.)

Their guide, John Wetherill, took them to the cliff-dwellings of Betatakin and Keet Seel in the newly-established Navajo National Monument, for which he was the government-appointed custodian. (For more on Wetherill’s experiences in this role, see my article, “Trials and Travails of a Park Ranger: John Wetherill at Navajo National Monument,” in the October/November 2020 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

Continuing up Tsegi Canyon, the explorers came to a junction and proceeded up a short tributary named “Bubbling Spring Canyon.” After a short distance, they reached the foot of a trail that they followed up to the rim.

.”

They traveled for some distance across the tableland, skirting a geologic feature known as Tall Mountain. Somewhere along the way, they encountered a Navajo weaver working at her outdoor loom near her hogan.

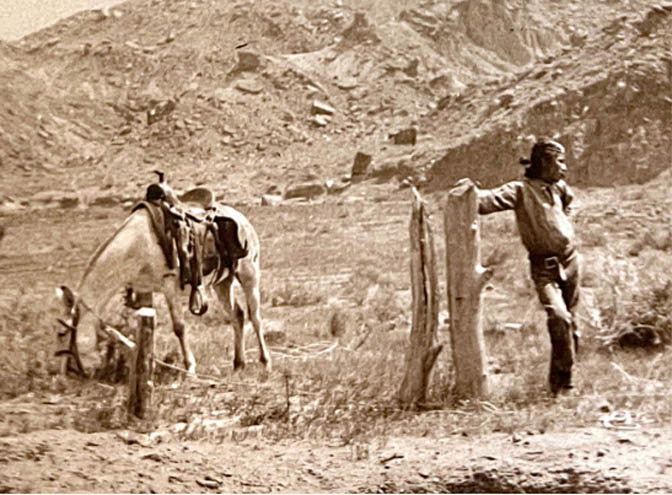

Their next significant obstacle was the deep, steep-sided Paiute Canyon. They reached the bottom of it on a Native American trail and came to the well-watered area known as the Upper Crossing. Nearby was the home of the respected, young Paiute man named Nasja Begay (Son of Owl) who had guided the pioneering 1909 expedition to Rainbow Bridge. Martha took two photographs of him near his home.

The team exited Paiute Canyon via another steep trail and set up camp at Tse Ya Toe Spring. In full view to the north was the imposing Navajo Mountain, which they ascended the next day to attain an even grander view.

The adventurers then backtracked to the base of the mountain and began circling it in a counter-clockwise direction on their way to the rough country that was still between them and Rainbow Bridge.

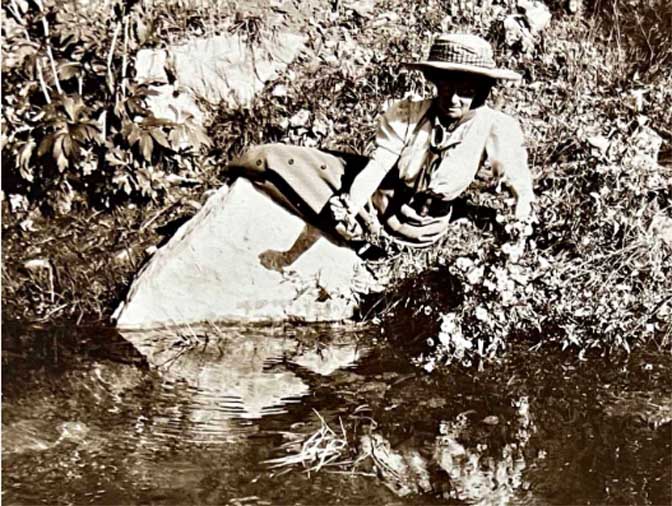

Wetherill planned their route and itinerary to ensure that it included adequately-spaced stops where they could replenish their water supply. In one of the dry stretches, distant from springs or streams, they found natural potholes in the rock that fortunately contained rain water.

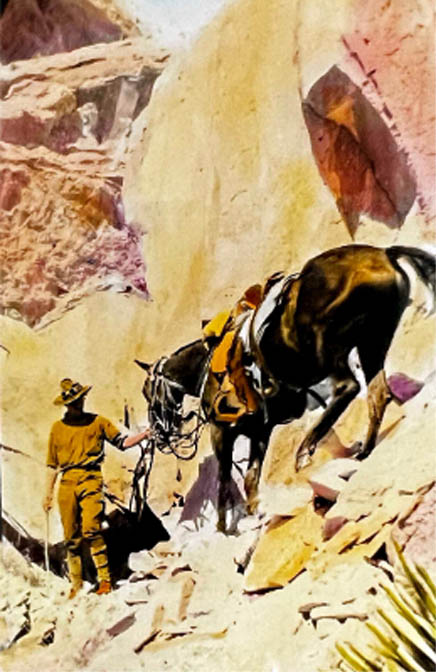

North of the mountain, the terrain became more challenging. Along some of the more precarious stretches, they found it prudent to get off their horses and walk, lest a slip cause calamity to both horse and rider.

“Along an edgy edge.”

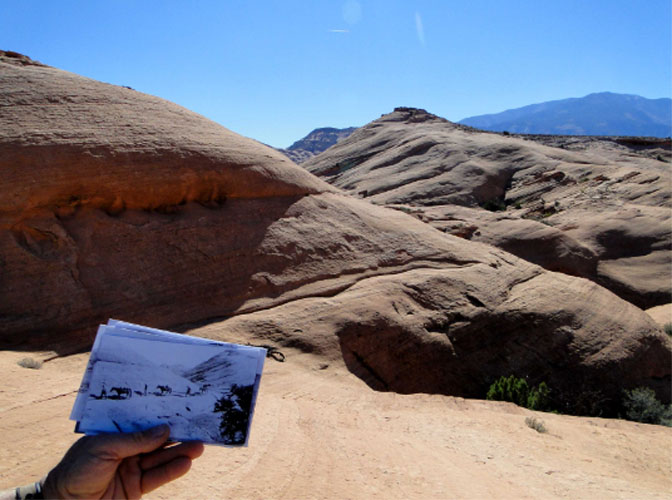

Some of the scenes in the Wadsworth photos can be matched along the modern Rainbow Bridge hiking trail, but many others cannot. I learned that a shortcut was constructed in 1933 by the Civilian Conservation Corps, which bypasses some of the more dramatic sections of the old route. After several exploratory treks, and with the aid of vintage photos, we were able to relocate the historic trail.

relocating abandoned, unmapped routes.

It is thrilling to retrace the footsteps of early explorers through rugged, out-of-the-way places. Being there elicits a sense of appreciation for their fortitude as they traversed terrain that is, in places, so steep that it is only marginally negotiable. In the photo captioned “Coming down over the rock hills,” the man in back is leading his horse down some cut steps. Those were already there when the first expedition of record descended this slope in 1909, and they were said to have been created by the noted Navajo head man, Hoskininni, when he and his family were eluding the American solders during the Long Walk period in the 1860s.

It was this part of the trail that likely led to Nelka’s description of a “hopeless, shapeless chaos.” Her strong aversion to the landscape is somewhat puzzling, considering the glowing accounts of many other visitors. Her consternation can be partially attributed to the physical difficulties of the trip, but also to a particularly disturbing mishap she witnessed. “On the way there Mr. Whiterill [sic], our guide, fell over with his horse when it was impossible to keep balance,” she wrote. “He got loose, the horse fell over backwards several times, broke its neck, slid down sheer rock and fell about 50 feet over a cliff, the sound was awful.”

Back in those days, travelers to Rainbow Bridge had to laboriously scramble over stretches of steep and rocky terrain to circumnavigate sheer cliffs and boulder fields. It is amazing and fortunate that nature made a way, although long and difficult, that people and horses could use to reach the natural wonder.

By almost all accounts, the journey to the bridge, though difficult, was worthwhile and even inspirational. Writer Zane Grey made his first trip there in 1913 and titled his next romance novel The Rainbow Trail. “It is a safe thing to say that this trip is the most beautiful one to be had in the West. It is a hard one and not for everybody,” he wrote. When rounding the last bend of the canyon and seeing the looming stone span for the first time, most visitors were awe-struck. Zane Grey expressed it best: “But this thing was glorious. It absolutely silenced me. My body and brain, weary and dull from the toil of travel, received a singular and revivifying freshness.” Martha must have been impressed, as she included several hand-colored transparencies of Rainbow Bridge in her slide show.

On their return trip, the adventurers backtracked for about twenty-five miles, then joined a different trail from the one over which they had arrived. Several miles east of Navajo Mountain, they arrived on the western rim of Paiute Canyon at the head of a dizzyingly steep trail that led them down to the Lower Crossing.

Paiute Creek and a nearby spring provided irrigation for small farms, one of which was owned by Nasja Begay’s father, Nasja (Owl). He treated the travelers to a fresh watermelon feast.

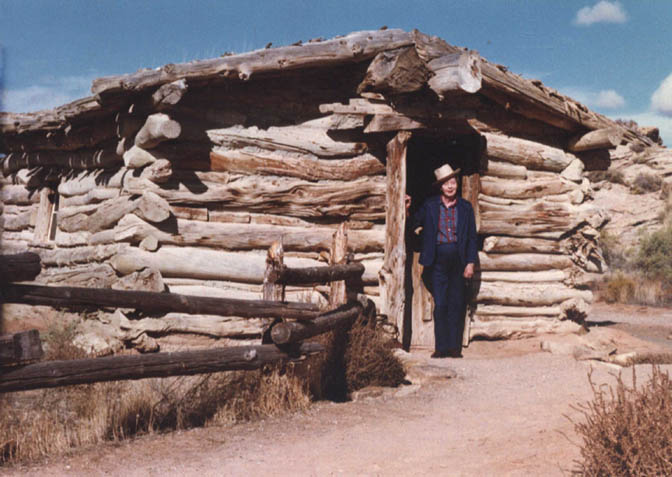

Wetherill then led the group out of the canyon to the top of Paiute Mesa, down another precarious trail into Nokai Canyon, to its mouth at the San Juan River, up Copper Canyon, and on to his home and trading post at Oljato, Utah. The expeditioners set up camp in the Wetherills’ yard.

After resting for a spell, the visitors resumed their long ride back to the railroad at Fort Wingate, New Mexico.

Nelka’s disenchantment with the Rainbow Bridge trail was due, in part, to her lack of experience in horseback riding through extremely rough terrain, and, perhaps, to the unfamiliarity of her horse with such conditions:

“I refused to mount my horse firmly and flatly until we got out of the worst part of the canyon, so I walked 12 miles when I had to pick every step on sharp stones. On the way back, Pat’s horse went head over heels down another steep place but was not killed. Still a few miles further my horse slipped going over a huge mass of rock as smooth as an egg and about the same shape and everyone thought he was about to be hurled to instant death, when by a miracle he screwed around, got himself up and caught his footing again. My mental agony had been so great that I had not a bodily sensation. I took my blanket, rolled up in it and went to sleep by some trees under some branches and a log. We came over the rocks where one misstep would have sent the horses to the bottom. No place even to spread his four feet before the next step. My heart was in my mouth most of the time.”

Nevertheless, Nelka felt some ambivalence about the trip. “I don’t know what impression you might get from my letter,” she wrote her aunt. “I have seen the most beautiful sunsets, but there are more essential elements than these to live in peace and the limits of what I can do now are very marked. I am wound up to the last degree. There are lovely Indians here.”

Despite her distress, the trip undoubtedly had a remarkable strengthening effect on Nelka’s character, which served her well during her continued charitable work with injured soldiers in war zones of Europe. She married a Russian aristocrat, Michael (Max) Moukhanoff of St. Petersburg. Nelka and Max had some remarkably daring experiences together. For example, during World War 1, Max was employed as an interpreter for the British Embassy in St. Petersburg. Toward the end of the war, the Russian government turned against England and ordered the secret police to execute the Russian officers who were working for the British. Max and Nelka made a daring escape to Finland in the dead of winter, which involved miles of walking and sleeping in the snow.

Nelka’s kind and accomplished aunt, Martha Wadsworth, undoubtedly found much more of value in their ambitious trek, as evidenced by the fine collection of photographs and lantern slides she created and preserved. Having no children, she bequeathed part interest in her estate in Avon, New York, to Nelka. It was there that Nelka passed away in 1963 at the age of 85.

*****

“The most wonderful of all melons (Nasja standing).”

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

To peruse all of Harvey’s brilliant Zephyr contributions, click here.

TO COMMENT ON HARVEY’S STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

Signed copies

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

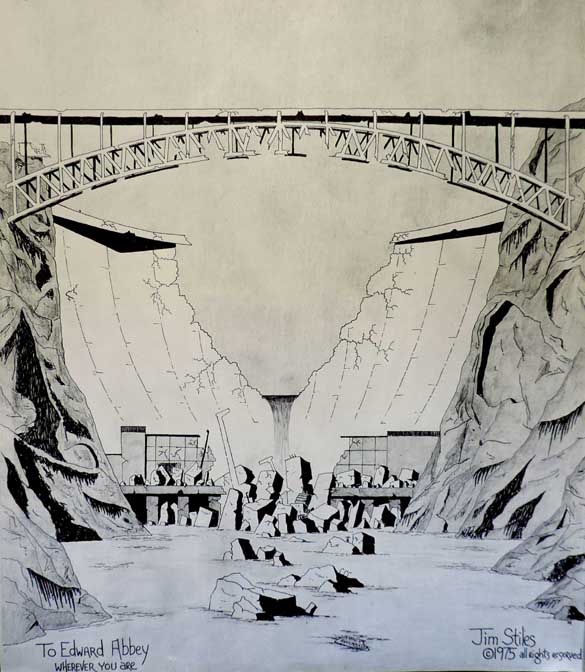

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

by Jim Stiles https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/07/30/tom-arnold-moabs-vw-mechanic-philosopher-ed-abbeys-pilot-zx73-by-jim-stiles/

—Jim Stiles (ZX#69)

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/07/02/should-arches-wolfe-ranch-be-re-renamed-turnbow-cabin-jim-stiles-zx69/

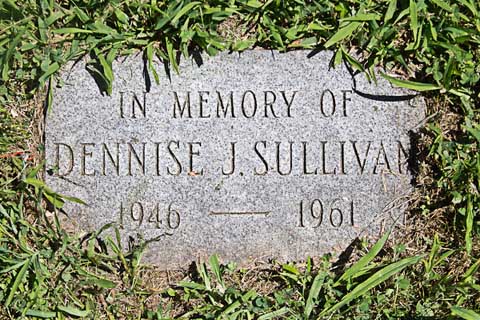

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/06/11/roaming-glen-canyon-the-four-corners-w-ruben-beth-nielsen-zx66/

And once more, now that you’ve read the latest Zephyr Extra and waded through the ads, please take a minute to comment. Thanks for your support…. Jim Stiles

The pictures are absolutely beautiful, frightening !! I thought I was adventurous but the kind of trip to Rainbow Bridge would’ve paralyzed me, I think!! How these women even survived it on horseback is a miracle in itself! But how wonderful that Leake had access to them and even more miraculous that Mr. Wetherill, suviving the death of his horse, recorded all this adventure! Not for the faint of heart!

The so-called civilized human mind under the influence of wealth and religion confronts a landscape not made for humans. I never tire of the spectacle. And just last week, another National Monument added to the list. Thank you, Harvey Leake!

Thank you Jim Stiles for what you do.

Thanks Jim!

This is great, Harvey. Have always been fascinated by the Wetherill adventures, as I am related to them through Isabelle Wetherill Eaton. Thanks so much for all the great images and information.

Beautiful tour of country and rare history of area, especially Navaho life and before it all became a tourist site, from one who also had opportunity to discover Glen Canyon 1961-62 to conserve its history! Keep up great history work Harvey and Jim Stiles. Also Glen Canyon Institute!

I just picked up a copy of Cyde Kluckhorns journey to Rainbow Bridge. Thrift store purchase. Great story.

Years back I had a trail-side chat with a couple of riders on Mules. They were bragging how fearless and

sure-footed their mounts were. They did a little rock-crawling for proof. Up the boulder, turn around, pose,

then down again. Mule looked almost smug. When we reenact this expedition,, could we take Mules instead

of the sketchy Ponies?

Epic trip and story.

I’ve wanted to go up Navajo Mountain and gaze in all directions for decades. Yet Rainbow Bridge only

holds a mild interest. Go figure.

I backpacked with friends around the north side of Navajo Mountain to Rainbow Bridge in 1981. Thanks for the wonderful color images. They brought back great memories!