NOTE: A couple weeks ago, I posted a story about rock inscriptions. I asked the question, ‘When does graffiti become historical and a valuable artifact of the past’? When I worked at Arches National Park in the late 70s and into the 80s, my boss, Chief Ranger Jerry Epperson, assigned me and others the task of doing one thing. Every work week, Jerry wanted me to— explore. He wanted all of us in the ranger division to know the most remote sections of Arches. A year later, he added the ‘task’ of searching for and recording undocumented arches. As it turned out, there were thousands. I also loved finding and recording the old rock inscriptions on the canyon walls. To me, if they dated back to the pre-Arches Monument days, they had historic value. My proudest “discovery,” though it was purely by accident, was left by a fur trapper and trader named Denis Julien. What follows is an excerpt by author James Knipmeyer about the life and times of the man we know so little about. Here is an excerpt from Jim’s excellent account. Following his excerpt is a short epilogue by me, and the response my accidental discovery created…JS

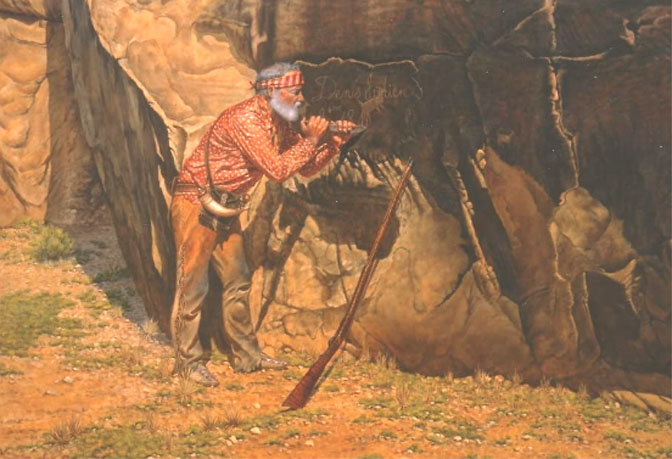

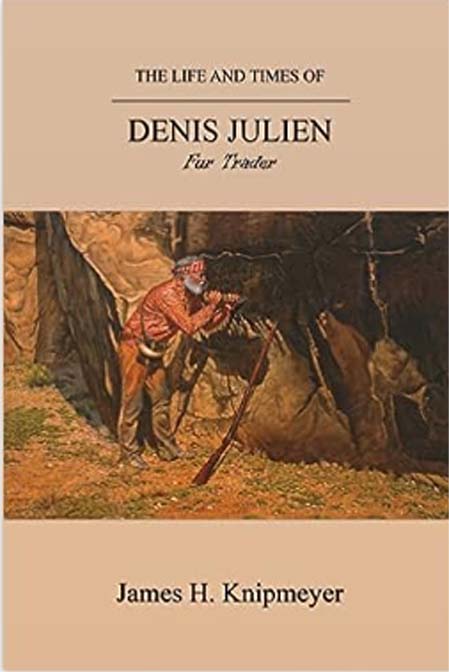

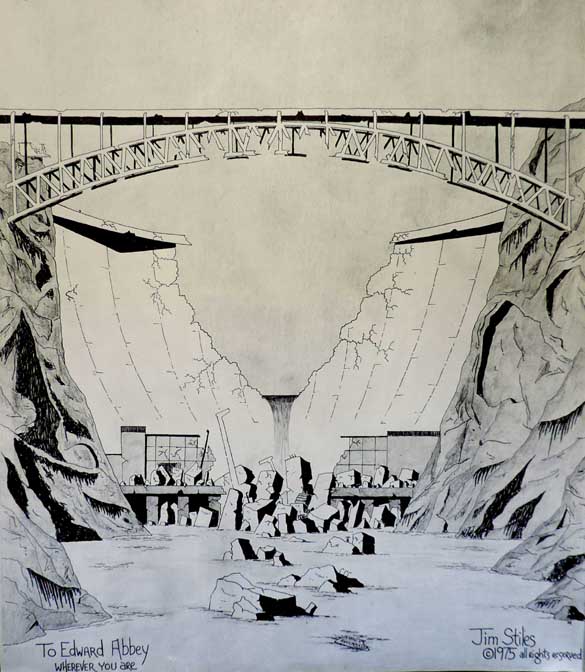

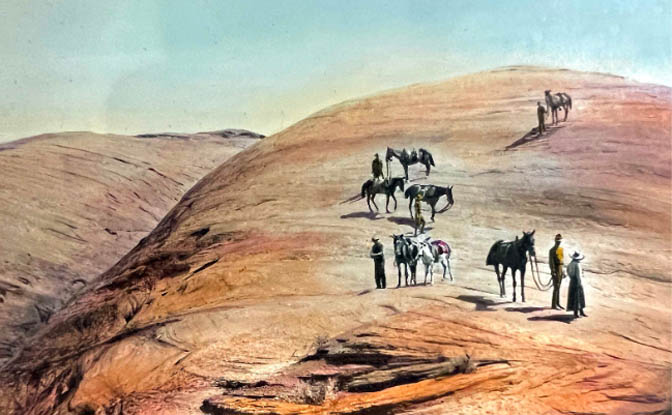

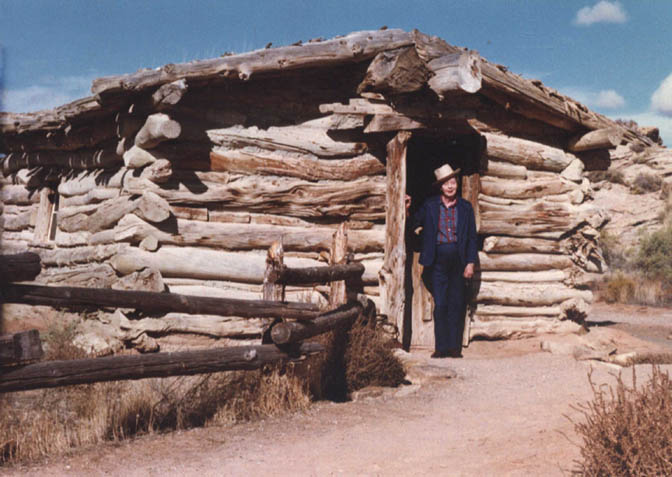

The painting is by the brilliant Moab artist Pete Plastow.

Pete passed away in 2021. For more on this great artist and wonderful man, click the hot link above.

On the morning of March 22, 1798, the Spanish gunboat La Flètch pushed off from the levee of the St. Louis waterfront into the roiling, muddy waters of the Mississippi River. The vessel was on its way upstream to the French village of Prairie du Chien, in present-day Wisconsin. On board was François Cailhol, interpreter and guide, who also kept a journal as a form of report for the Spanish comandante. Seventeen days later, on April 8, and now some 250 miles from St. Louis between the mouths of the tributary Iowa and Rock Rivers, they met a canoe being swiftly paddled downstream and manned by six men.

In his journal, Cailhol named each of the six canoeists. One of these was “Denis Julien.” Cailhol added that “On this day we met… their bark canoe loaded with furs.” Simply put, Denis Julien was a fur trader…

After spending at least thirty years in the fur trade of the Mississippi and Missouri River region of the Midwest, Julien made a major life-change and removed to the then Mexican-owned territory of what is now the American Southwest.

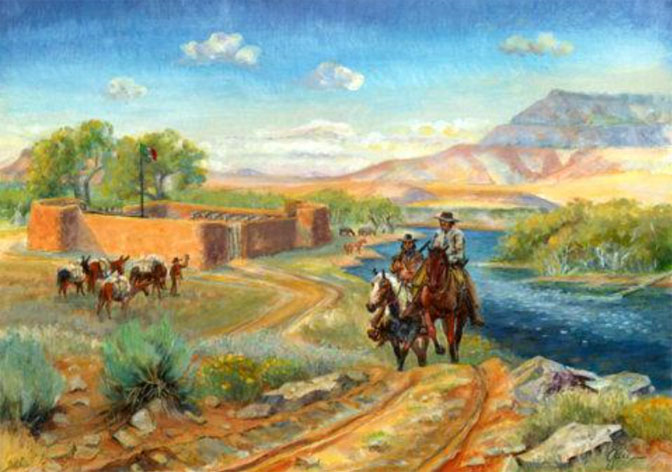

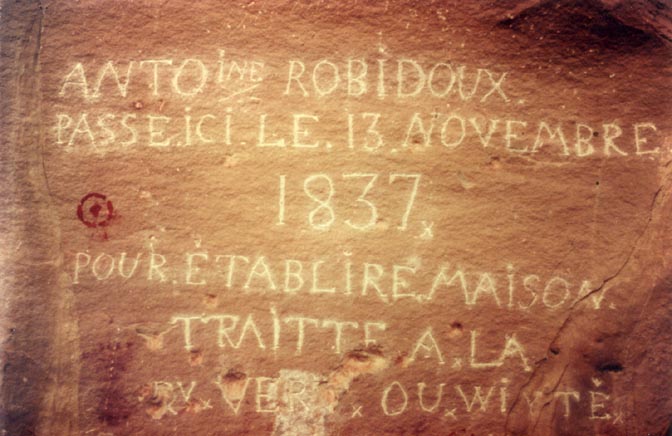

By the mid-1820s brothers Antoine and Louis Robidoux, who maintained residences in Santa Fe, had also established a trading house in Taos. In 1828, Antoine is reported to have traveled north from there and established a new trading post in the Ute Indian country. Located just west of the confluence of today’s Gunnison and Uncompahgre Rivers in western Colorado, it was called Fort Uncompahgre, the Ute word for “red water.” When Julien also traveled north in the spring of 1828, it would have been logical for him to have accompanied Robidoux as far as the site of his new post. But while Robidoux halted there and began construction of his fort, Julien continued on westward and northward to his ultimate destination, the Uintah Basin in Utah…

So, what were the intentions of Denis Julien, now at the age of around 55, in this new chapter of his life among the Uinta-at Utes? Perhaps not surprisingly, he was to continue what he had been doing for at least the past thirty-five of those years – conduct a trading business with the local natives.

When Julien entered the Uintah Basin of present-day northeastern Utah, he was not alone. According to native Ute traditions there were at least two other persons with him, and perhaps as many as “four to six.” Those named were William Reed, his young nephew James Reed, and Denis Julien… In the Ute stories there is often included a fourth member of the party, Auguste Archambault (or Archambeau)…

Their new trading establishment soon became known as the Reed trading post, and later Ute informants remembered a white man they called “Sambo” and another one called “Julie.” This was obviously a reference to Auguste Archambault and Denis Julien. The post itself was a single log cabin near a spring of water just north of the fork of Whiterocks Creek and the Uinta River…

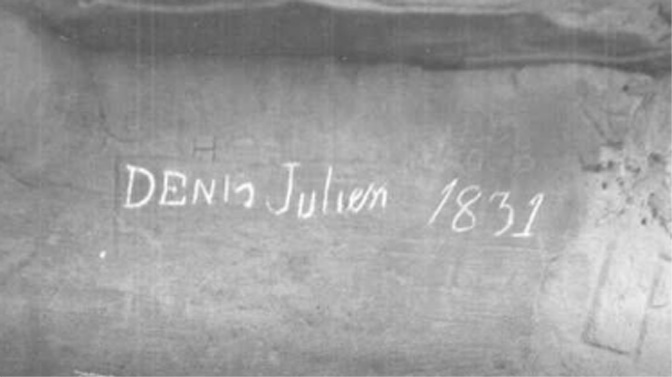

In the next couple of years, Julien carved his earliest known inscription, his name and the date, in the Colorado Plateau region… Located not far back from the banks of the Uinta River about seven miles below the Reed trading post, it was incised, perhaps with a horseshoe nail or metal awl, into the sandstone of a rocky outcropping sometimes today called Face Rock, because of its silhouette. It reads simply, “Denis Julien 1831.” What induced Julien to carve his name and the date is not known. While none like it have ever been found back in the Midwest, about a dozen such inscriptions have been discovered across the Colorado Plateau…

In 1832, the Reeds sold out to Antoine Robidoux. When he took over the trading business in the Uintah Basin, he erected new buildings on the opposite side of the spring from the old Reed post, just a little to the north and on higher ground. This became known as Fort Uintah, which the early trappers and traders pronounced “Winty”…

In the winter of 1830-31, a large party of American traders and trappers had traveled westward from Santa Fe all the way to California, returning the following spring…

Julien undoubtedly heard stories of this new route leading west from the Green River, and perhaps after the sale of the Reed trading post in the spring of 1832, he decided to see it for himself. It is debatable among modern historians if Julien ever did get as far as California, but it is known for a fact that he did travel to at least the eastern slope of the Wasatch Plateau in west-central Utah. Years later, in 1875, United States geologist Grove K. Gilbert found a carved inscription, either along present-day Ivie Creek or its tributary Red Creek. It read, “D. Julien 10 Mai 1832”…

Not long after his sojourn westwards, Julien probably remained and very likely worked for Robidoux…

Robidoux stocked Fort Uintah from his trading house in Taos via his Fort Uncompahgre post in western Colorado… Coming down Hay Canyon of the Tavaputs Plateau, on the sandstone cliffside near an excellent spring, is found “D. Julien 183-.” Unfortunately, the last numeral has been lost to the ravages of time and weathering…

From 1824 until the first part of the 1830s, the American trappers from the northeast and the New Mexican-based traders and trappers from the southeast, did an almost too good of a job harvesting the beaver population of the region. As early as the 1833 annual rendezvous, one of the St. Louis traders observed that some of the trappers were thinking about moving to another section of the country. There was reportedly a large tract of land far to the southwest which was said to abound with beaver. This was probably the canyon country of the Colorado Plateau…

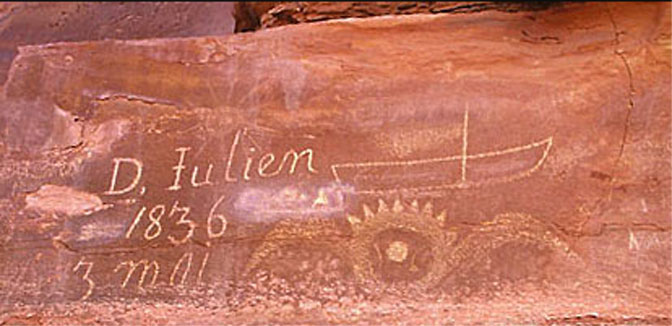

By at least 1836, Julien himself had entered the depths of the Green and Colorado canyons, perhaps to scout out potential beaver possibilities. At least four inscriptions were left there by him. One is located some 600 feet above the bank of the Colorado River, not far below its confluence with the Green. It appears to have been hastily scratched into the side of a large rock boulder and now faintly reads, “Denis Jul— Mai — 1836.”

The location of this inscription site is an unusual one, but is adjacent to a long-used Native American trail leading out of the canyon to the plateau rim high above. The spot would have provided Julien with an excellent view for about two miles downriver and overlooking the first three rapids of Cataract Canyon. Another inscription, some thirty miles on downstream near the foot of the canyon, read simply, “D. Julien 1836.” This would seem to indicate that he did in fact make it through the treacherous whitewater of Cataract Canyon.

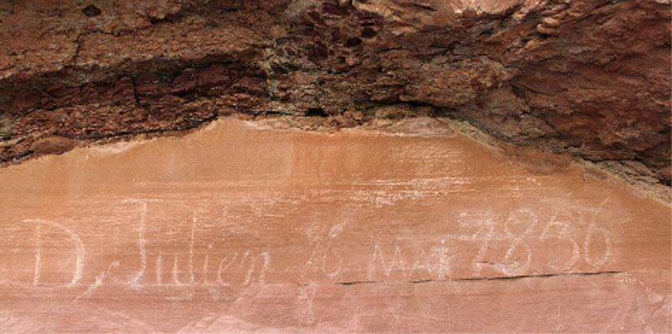

The other two inscriptions are found along the banks of the Green River, in what is today known as Labyrinth Canyon. The first is located some 200 yards back from the river. It reads, “D. Julien 1836 3 Mai.” The next is found almost twenty miles farther upstream, just a few feet from the water’s edge, and is dated, “16 Mai.” This would mean that Julien took thirteen days to travel some twenty miles up the river. This is not altogether unreasonable, considering that he would have been traveling against the current and was also likely scouting out the possibilities for beaver trapping.

At the “3 Mai” Labyrinth Canyon inscription, just inside the mouth of the side-canyon called Hell Roaring, immediately next to Julien’s name and the date is the crude carving of what appears to be a boat, with a straight vertical line extending upward from its bottom. This last has been interpreted by researchers and modern-day river runners to represent either a mast for a sail or a so-called setting pole. Either or both would have aided Julien in making his way upcanyon utilizing the upstream eddies of the river current.

Just below this etching is what appears to be a “winged sun,” but which has been identified by Ute informants as a male prairie hen, flying straight toward the observer. Therefore, it has been surmised by some historians that perhaps Julien was traveling with a Ute Companion…

After his 1836 venture south into the canyonlands, Julien continued to remain around the Uintah Basin region. His next carved inscription is found in the upper part of the Green River’s Whirlpool Canyon, not far below what was known to the trappers as Pat’s Hole – the Echo Park of today. The nearby inscription, located close to the bank of the river, consists of the initials “D.J.” and the year date of “1838.” Though his name is not spelled out, the carving is undoubtedly that of Denis Julien, as the capital letters and numerals are made in the exact same fashion and style as his other full name inscriptions…

Sometime in late September or early October of 1844, Utes attacked Robidoux’s Fort Uintah trading post… One contemporary story stated that at the time of the attack, the fort had very few of its usual inhabitants present, many having already departed because of the increasing tensions with the neighboring Uinta-ats. Denis Julien seems to have been one of these.

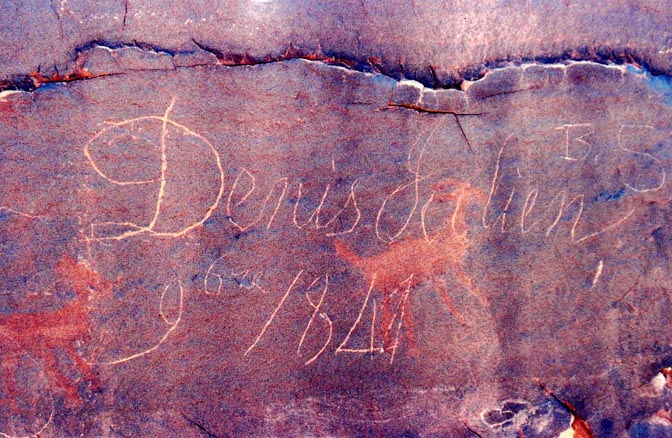

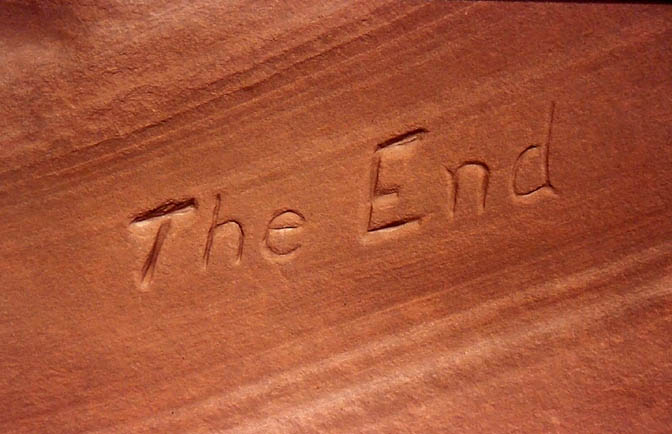

Far to the south, in the Devils Garden section of present-day Arches National Park, is the last known, chronologically, Julien inscription. It has been scratched into the dark, desert-varnished side of a tall sandstone fin and reads, “Denis Julien 9 6 me 1844.” The “6 me ” is the French equivalent of 6 th in English, sixth in French being sixième. The preceding numeral “9” is representative of the ninth month, September…

But Denis Julien had not reached his early 70s by being careless in possible hostile territory. He was undoubtedly aware that a band of the Sheberetch Utes, who lived mostly in today’s Spanish Valley-La Sal Mountain area of eastern Utah, commonly camped near the usual Colorado River crossing to collect “tribute” for the safe passage of American or Mexican trading parties. With bad feelings running high even before the burning of Fort Uintah, Julien would have wanted to avoid any chance encounters with Ute natives. Therefore, some twenty miles north of the normal crossing near today’s town of Moab, he would have had a choice of trails to follow.

While the main route of the so-called Spanish Trail led south to the Moab crossing, another branched off to the southeast down present-day Salt Valley. It then led up the smaller Cache Valley and finally down a steep, little-used trail that crossed the Colorado several miles upstream from the principal crossing. The wily Julien, veteran of many years among various Native American tribes, chose this latter route of travel. Still exercising caution, he made his night’s camp up and over the bordering cliffs of Salt Valley, about a mile away from the trail itself. There, in the shelter of a towering sandstone wall, down in a hollow of sand dunes among some pinyon and juniper trees, he left his 1844 name and date.

This seems to be the last definite notice that history has of the existence of Denis Julien.

Missouri native James Knipmeyer has been hiking and backpacking in southern Utah and northern Arizona for over fifty years and has published numerous articles about the region’s history. His books include Butch Cassidy: Historic Inscriptions of the Colorado Plateau, In Search of a Lost Race: The Illustrated Exploring Expedition of 1892, Cass Hite, The Life of an Old Prospector, and Joe Duckett: The Hermit of Montezuma Canyon.

A SHORT EPILOGUE ON RE-DISCOVERING THE JULIEN INSCRIPTION —Jim Stiles

As I noted in the prologue to this story, one of my “duties” as a ranger was simply to explore. My boss wanted us to be familiar with every corner of the park and so whenever possible, we took him at his word. I’m sure there are parts of the park that haven’t been visited (by humans at least) since my last hike.

So on that hot July day, I was following the ridge of the Devils Garden far beyond Dark Angel, and was on a sandy ledge that actually looked down at a small protected area (from the elements) and the endless rows of vertical sandstone fins that run for miles. Even from a distance, I could see some inscriptions on the desert varnished wall and assumed I’d find more Basque carvings. They were names I had even become familiar with from other locations. But in the middle of these inscriptions I saw the Julien name for the first time. It didn’t stand out like the rest, but it looked authentic, partly because the date seemed to be written in French. What graffiti vandal would take the time to do that? I took a couple photos and eventually returned to the trailhead and park headquarters. In those days, rangers were supposed to fill out a form called a “case incident report,” or better known to us, a “10-343.” Though this wasn’t really an incident, I wrote it up anyway. I had heard of other Julien inscriptions along the Green River, and was sure this carving was already known.

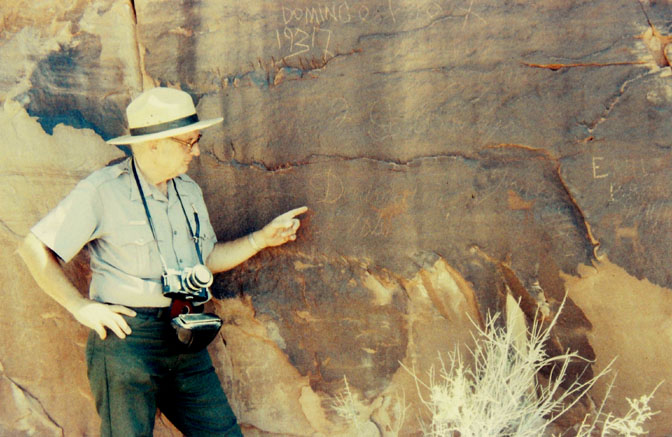

To my surprise, a historian named John Hoffman, who was in fact writing a book about Arches, somehow heard about my find. I showed him the photos and he was sure it was authentic. He called the legendary river runner and historian Dock Marston. Dock was so excited that, although his health was failing, he caught the next possible flight to Salt Lake City. Hoffman picked him up and we all met at the Devils Garden trailhead. Dock was not well enough to make the eight mile round trip, but John brought a Polaroid camera (yes, it was THAT long ago) so that he could show Dock the images as soon as we returned. Hoffman examined the inscription carefully, took many pictures and declared, “This is the real deal, Stiles.”

We showed the photos to Dock and he was as ecstatic if not more so. My one regret is that I had only been a ranger for a year and, incredibly, I didn’t know who Dock Marston was. In the years to come, I’d hear many stories and yarns about Dock. The best comes from Ken Sleight an the story of Bert Loper’s bottle of whiskey. But I’ll save that story for another time…

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. WE GREATLY APPRECIATE YOUR INPUT & ANY ADDITIONAL INFORMATION YOU CAN ADD TO THE STORY…THANKS—Jim Stiles

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

Signed copies

“sign me up” in the subject line. cczephyr@gmail.com

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

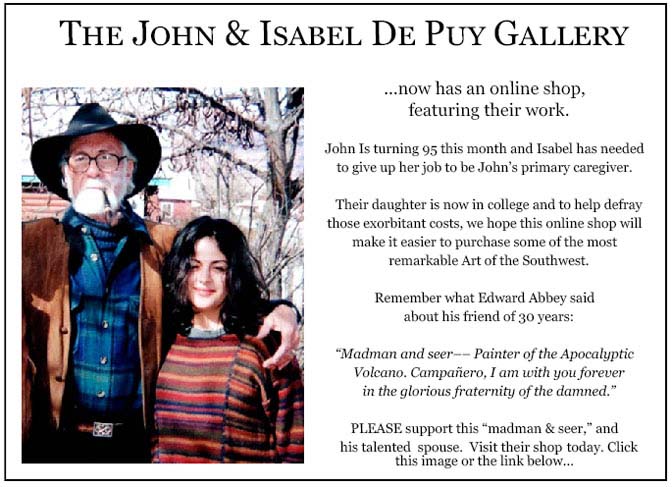

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

—Jim Stiles (ZX#76)

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/08/20/the-zephyr-america-files-volume-1-horses-sunsets-grain-silos-tucumcari-pinky-jim-stiles-zx76/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2023/07/02/should-arches-wolfe-ranch-be-re-renamed-turnbow-cabin-jim-stiles-zx69/

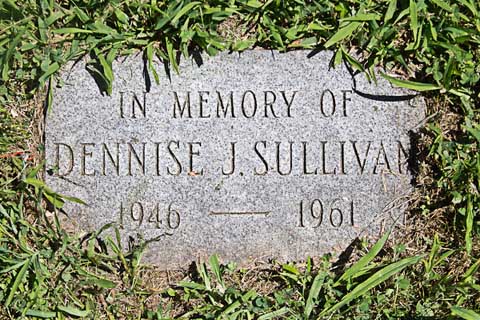

(My Recent Encounter with the Mental Health Industry) ZX#20

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/08/07/grief-meets-orwell-the-cuckoos-nest-by-jim-stiles-my-recent-encounter-with-the-mental-health-industry-zx20/

And once more, now that you’ve read the latest Zephyr Extra and waded through the ads, please take a minute to comment. Thanks for your support…. Jim Stiles

Love it Jim! Took me 22 years to find the “16 Mai” inscription, but all the other river level ones I’ve found over many, many trips over the years.

Even the first paragraph had me intrigued…a Spanish gunboat (sailing with a keel?) up the river from St. Louis in 1798. Spain guarding her (temporary) ownership of the Mississippi…that would’ve been a sight….

Applause!!How great that you discovered that “graffiti” and to think what that explorer went through in those early days as he traveled the many miles between his signatures! This type of history is fascinating!

Thanks Donna. I think you’ve become the Zephyr’s #1 commenter. I’m always happy to see your observations here.

Keep sharing.

STILL MIXING THE IMPORTANT FROM THE PAST WITH THE PRESENT.

AND WEARING FLEECE VESTS AND TUCKING IN MY SHIRT.

Clark Trowell

Thank you! Cool stuff!

Thank you for this. Love the history. I believe I’ve seen (and photographed?) one of the Juliene inscriptions along the Steel Bender trail above Ken’s Lake/Faux Falls. I got there via the Meader Ranch (aka Ken’s Lake) road. I’m sure you know of it but I can’t find it anywhere on-line. Am I mistaken? Do you have images of it?

I’m not familiar with that inscription and I’m not sure if Jim Knipmeyer is either. Do you have photos of it, because it doesn’t seem to fit the itinerary Julien would have taken.

Thanks Jim for the Knipmeyer excerpts–excellent research he brought together–and thanks no less for the Plastow painting especially, and the Baker painting as well. They are both new images to me and beautifully executed. I can picture Denis Julien pecking away out there–perhaps alone.

We may note too that the upcoming Thursday this week–August 31–actually is a Blue Moon. Thanks for a True Blue Moon Extra.

Thanks Tim. And I was glad to have the chance, via Jim Knipmeyer, the chance to publish Pete Plastow’s magnificent recreation of that moment in time…. You might remember, a couple weeks ago, I had a post about inscriptions that included Julien’s. A couple readers were furious that Julien had defaced the petroglyphs. But imagine. It’s 1844 and Julien was most likely alone, in some of the most rugged and different to traverse terrain in the West. And by sheer chance he walks down that Sandy slope to the base of the Entrada sandstone fin, and sees those petroglyphs. It may well have been comforting to him, to see that someone else had been here.

I wonder if Julien ever pondered the idea of future historians tracking his wanderings from the on-and-off discoveries of his rock signatures. He was probably thinking something along the lines of “nobody will ever see these signatures, who the hell wants to come to these godforsaken places?”

Had the same thoughts !! Haha

It seems to me that people have a desire to communicate with folks that will come after in some way. A name and a date might someday surprise someone and make a connection. In this case a nearly 200 year old connection. He may have been inspired by someone else’s inscription. Great story.

Jim,

Keep up the articles like this, but please don’t ever go exclusively to farcebook, or you’ll lose this ol desert rat…I just don’t go there. One note about the Robidoux inscription in the Bookcliffs, it is on private land, which I found out the hard way about 40 years ago…loaded up the kids one Sunday to show them some history. I had been past it several times and others always talked about seeing it so I had no idea it wasn’t on BLM. We had just gotten unloaded when I heard a door slam and a pickup come blasting over from the ranch across the creek. Guy jumped out and went into a rant about trespassers, vandalism, blah blah blah…after a minute he recognized me, he had been a neighbor of my parents before he moved out to that ranch, and calmed down a little. Told me I could go ahead and look at the inscription, but my wife was so pissed by that time she said let’s just get out of here…not the best Sunday excursion ever…

Keep up the good work.

Ron M.