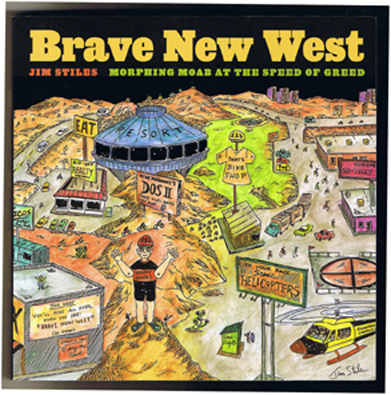

In the spring of 2007, the University of Arizona Press published my one and only book. “BRAVE NEW WEST: Morphing Moab at the Speed of Greed.” It vas a modest failure though it did sell out the first printing. But UAP, for reasons I never completely understood, chose not to do a second printing and the book went out of print completely. I bought the last 100 copies and if demand doesn’t increase, I plan to be buried with them

It did occur to me that I now owned the rights to the book, and since I feel like “dog-bottom pie” right now (a line I stole from Utah Phillips, I thought I might publish a few chapters from it, until I get to the point where I can count on the fingers on my hand…So return to those quiet days of yesteryear…just 16 years ago.,,JS

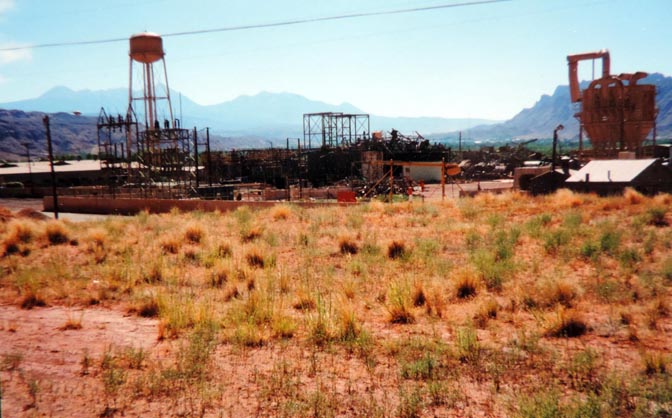

In the summer of 1987, the economy of Moab and Grand County hit rock bottom. A few years earlier, as uranium prices plummeted, the Atlas Vanadium Processing Mill north of town closed its doors for good. The mill, which had at one time provided hundreds of jobs now lay silent. It seemed as if the mainstay of Grand County’s economy had vanished overnight and Moab was ghost town bound. Unemployment reached 20%. Empty homes and ‘For Sale’ signs were everywhere; at one point as many as one in five homes was on the market. The way the story went: Everybody moved to Elko, where the mining industry was still viable.

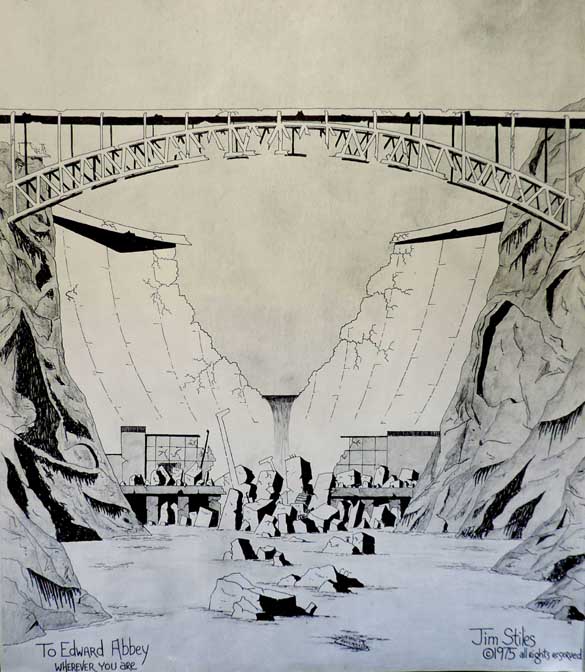

Moab’s politicians and promoters tried to stop the town’s dwindling population and shrinking tax base but Moab was hemorrhaging to death. For a while, in the early 80s, as the Department of Energy searched for a place to store the nation’s high level nuclear waste, a remote location in San Juan County, just a thousand feet from the boundary of Canyonlands National Park became one of the primary sites for the “repository.” The plan was to excavate a huge chamber in the massive salt domes, thousands of feet beneath the surface and store the radioactive material in canisters. The subterranean vaults and the canisters needed to withstand the forces of Nature for about 10,000 years. Considering this was a government operation, many of us were skeptical. In addition to the repository site, the associated infrastructure needed to deliver the goods would have been staggering. DOE proposed a railroad line from Moab, downriver to Lockhart Basin and the base of the Needles Overlook to the site. The view would have never been the same. But Moab, still very much a town with a mining mindset in 1982, voted 2 to 1 in favor of the Repository in a non-binding straw vote.

Moabites debated the Repository at public meetings with the same amazing regularity and enthusiasm that we devoted to other contentious issues over the years. Again maybe there just wasn’t anything else to do in those days but argue, but participation remained spirited and well-attended. Abbey’s presence at these meetings, either live or by proxy may have boosted attendance. When Ed didn’t feel up to the task, he often sent his young bride Renee’ to read his prepared comments–we usually preferred looking at her anyway.

But more often, the Great Debates were waged with remarkable civility at Moab’s three greasy spoon diners, the Westerner Grill, Milt’s Stop n’ Eat, and the Canyonlands Café.’ Milt’s was named for its creator Milt Galbraith who built the Stop n’ Eat in 1951 with $10,000 he borrowed on a handshake (He paid off the loan in a year). Milt and his wife Audrey ran it 14 hours a day, six days a week, 50 weeks a year until 1982, when they finally sold the Stop n’ Eat and settled into a comfortable, if not wealthy, retirement. The Westerner and the Café’ had origin stories of their own, and the cuisine at all three was similar—-what made them so special were the seating arrangements. Even when tables or booths were available, they were few and far between and most of us were thrown into the mix at the counter. You never knew who your dining companion might be on any given day–it made for interesting conversation.

The L-shaped counter at the Westerner and the Café especially encouraged animated cross-talk from all the customers. My favorite lunch partner was an ex-uranium miner named Neldon Lemon. We’d been at the same meeting the night before and I’d overcome my fear of public speaking to stutter a few words. Neldon wasn’t pleased and when he sat down beside me and I attempted to introduce myself, he cut me off…

“I know who you are,” he snarled. “You’re one of them goddamn environmentalists that wants to lock everything up.” He looked at me fiercely.

“Well,” I said, “That must make you one of those uranium miners who wants to tear everything up.”

Neldon squinted at me for just a moment and then shook his head and chuckled. “Ah what the hell. I guess I can tolerate sitting next to you. What’s the special today?”

That’s the way it often was at the Westerner. Neldon and I became friends over the years. We chose to disagree on many issues but we were able to acknowledge and even celebrate our common interests as well. We both chose to live a simple life away from the cities, we both loved the open space and freedom of the Rural West, and we’d both chosen Moab. What else mattered really?

Still, on one issue we saw the changes in Moab very differently.

By 1985 Moab was in a state of full “economic collapse.” For the old time Moabites, the ones who had cut their teeth during the Uranium Boom days of the 1950s, Moab’s demise was an unmitigated catastrophe. It was inconceivable to them, and heartbreaking as well, that the party was over. For almost 40 years mining had sustained the Moab community and now it seemed as if the town had nothing to show for its past success except boarded up Main Street businesses and half-deserted neighborhoods.

For another part of Moab’s dwindling population, however, the downturn in the economy offered an unexpected opportunity. Since the early 1970s Moab had become a mecca for a small but growing group of young pilgrims, for lack of a better word, and I was one of them. We were searching for a different kind of life, away from the polluted, frenzied madness of urban areas. In Moab, Utah, we thought we’d found it. Coming to Moab meant making some sacrifices. We knew we’d never get rich. We knew we had removed ourselves from cultural and social opportunities that we’d grown accustomed to in our old home towns. And we knew we’d probably always be a vocal but persistent minority in a very conservative part of the American West.

The end of the mining boom presented a disaster for some, and an unexpected dividend for others. With the exodus of the mining community, housing prices plummeted, but for the first time, all those seasonal rangers and river runners–the marginal citizens of Moab, like me–could suddenly afford to buy a home. We went from being bearded hippies to responsible land owners in eighteen months. I was one of them. I’d heard rumors that prices had fallen and I spent part of a day driving up one side street after another, stunned by the number of realty signs. Finally I spotted an old stucco home with a big yard and a magnificent spruce tree in front. A catalpa tree grew next to the driveway…it was a sign from my grandfather, for sure, who loved the catalpa’s spring blossoms but despised the seed pods. I decided to make an offer.

But I had no idea how to buy a house. I didn’t even know where to start, so I turned to Pete Parry, the superintendent at Canyonlands National Park and asked for advice. He had some and it was brief. “Go see Norma Nunn.”

Norma was a paragon of energy and assertiveness–-exactly what I needed to get me through this torture. I told her about the Locust Lane property and she knew it well. The bank owned the house, had been sitting on it for five years, unable to unload it. The last time the house sold, in 1980, it went for $51,000. Now the bank wanted $23,00.

“We’ll offer $18,000 and see what they do,” Norma explained. “How much of a down payment can you make?”

I’d checked my pitiful savings account. I barely had $2000 in the bank and during the off-season from Arches, I was living on unemployment.

“Two thousand? They might take that,” Norma assured me. “And be sure to list your unemployment compensation when you apply for the loan. That adds to your yearly income.”

I thought she was crazy. “Are you sure, Norma?”

“Absolutely….this bank does not want to deal with all these empty houses. My guess is, they’ll unload it at the price you’re offering.”

And she was absolutely right.

The next morning, I drove straight to town and walked warily to her desk. I stared disbelievingly at the documents she’d left for me. “Approved.” I was a landowner. A few weeks later, we closed the deal. My new home was a wreck. No one had lived in it for years. I didn’t even know if the plumbing and wiring worked…it was an “as is” deal. As I stood in the backyard, I felt a bit dizzy. What was I thinking? My doubting thoughts were pushed aside by a hard noise that sounded like a gravel crusher. But this was no mechanical clatter–it was Toots McDougald.

“Did you buy this goddamn house or are you just renting it?”

She was leaning against the fence that separated my place from hers. She looked to be in her 70s. Tall, angular, not an ounce of fat on her. She pulled her short closely cropped hair straight back, like Valentino. A cigarette hung idly from the corner of her mouth.

“Well?” she repeated, “Did you buy this goddamn place or not?”

I nodded slowly. “Yeah…for better or worse, I bought it.”

Toots shook her head. “Then I hope you paint those goddamn aluminum shingles up there on the roof. The glare from them shingles into my kitchen is just awful in the afternoon.” With that she threw down her smoke, stomped it out with her tennis shoes, and walked back inside.

It became clear to me that painting the aluminum shingle might be a wise priority and as a result, Toots and I became lifelong friends. In the years to come she would feed me chocolate cake, every time she wanted me to come outside and pull goatheads and remind me that if she were 30 years younger, “you wouldn’t be over there sleeping alone, honey.” Toots told me of her adventures as a little girl in Moab, of her long trail rides to Turnbow Cabin, of the sorrows and joys she’d endured and loved over the years and decades…she painted a picture of a Moab I had never seen.

But what about now? What was to become of Moab in 1987? With a dwindling population and few if any prospects for a brighter economic future, some thought Moab might literally dry up and blow away. But others saw Moab’s economic slump as an opportunity to re-define ourselves as a community. What kind of town did we want to be as we approached the last decade of the 20th Century? It seemed as good a time as any to abandon our title of “Uranium Capital of the World.” Moab had always been pushed and shoved along by a boomtown mentality. Maybe we could finally escape that kind of erratic life.

But how to make a living…that was the rub. In the waning days of the summer of 1987, Moabites began to realize how divided we still were on the subject. Rumors of a plan to build an incinerator–a toxic waste incinerator–at Cisco, Utah, 35 miles upstream from Moab, reached the local cafes. The debate began.

As summer turned to fall, hard information began to replace the gossip and the truth was disturbing. The Grand County Commission–Jimmie Walker, Dutch Zimmerman, and David Knutson–had been working behind the scenes for six months with a corporation named CoWest, Inc. CoWest specialized in building toxic waste incinerators and now they wanted to construct what they claimed would be a state-of-the-art facility on 180 acres of land in Cisco. But the land there was not zoned for that kind of use; in fact, there was no heavy industrial zone in Grand County at all, and the county commissioners, seeing a way to dramatically boost the county tax base, thought they’d stumbled across a gold mine. Or a high-tech toxic version of one. And they were convinced that the residents of Grand County would support them.

Jimmie, Dutch and Dave were all lifelong residents of Moab and survivors of the economic downturn. But none of them sensed how much Moab had changed in such a short time. Just five years earlier, in 1982, Moab residents had supported the proposed nuclear waste repository by a 2 to 1 margin, despite the fact that the facility was to be built within a thousand feet of Canyonlands National Park in San Juan County. So the fact that the commissioners enthusiastically supported an industry that would incinerate a staggering variety of toxins, from benzene and paint thinners to pharmaceutical wastes should not have surprised anyone.

But the community was enraged, or at least part of it; what no one could predict was the extent of the anger. Was this just another vocal minority? Or were we seeing a fundamental shift in Moab and Grand County attitudes? We were about to find out.

By late October, the incinerator was front page news into the Times-Independent and opposition was quick and fierce. A group calling itself the Colorado-Utah Alliance for a Safe Environment gathered 2000 signatures in just a few weeks from citizens in both states. But the petition had no legal standing and Commissioner Walker dismissed the signatures out of hand. “Those signatures don’t impress me at all…90% of the names came from Colorado.” Walker and the other commissioners called efforts by the opposition, “fear politics” designed to “scare the masses.”

Grand County residents kept scribbling anyway, but now they were signing their names to a petition that would put the issue on the November ballot. The Utah constitution provides a referendum provision to decide issues such as this; it requires 12.5% of the total number of votes in the last gubernatorial election. In Grand County, that meant 418 signatures. Three weeks later, sponsors of the referendum presented petitions to County Clerk Fran Townsend with more than 500 signatures. The petition asked that “Section 2-5-12-C of Ordinance 134, passed by the County Commission on January 25, be referred to the people for their approval or rejection at the regular election to be held November 8.”

One thing was certain, the “masses” were definitely scared—letters to the editor poured into the Times-Independent, mostly in opposition to the incinerator and the Grand County Alliance was formed to consolidate Utah opposition.

The Grand County Alliance was born one night in Castle Valley. Andrew Riley had caught wind of the rumor and shared this incredible tale with fellow residents Jayne Dillon, John Groo, and Dave Wagstaff. From that kitchen table, a strategy to combat the incinerator took root and the Alliance grew. An attorney and lobbyist from Salt Lake City named Ralph Becker offered hundreds of hours of free legal advice. Bill Hedden gave invaluable amounts of time, sifting through the scientific information. Kyle and Carrie Bailey worked tirelessly to organize and recruit new members to the Cause as did Lance and Larue Christie.

On the evening of December 2, 1987, a “toxic waste information meeting” was held at Star Hall. Commissioner David Knutson assembled a panel of CoWest officials, federal and state regulators, and private citizens. Almost 400 people crammed into the building for one of the most spirited gatherings in the town’s recent history. Dean Norris, the president of CoWest became an instant antagonist for incinerator opponents. Dressed in gray polyester and sporting a huge diamond-studded pinky ring, he barely tolerated the barrage of questions by angry residents that filled much of the evening and many of us could not have been happier; every cause needs a Bad Guy and Norris played the role perfectly.

When the shouting was over, nothing had been resolved and a showdown looked inevitable. The commission showed no sign of backing off and Moabites continued to vent their anger through the letters page of the T-I. Finally, on December 17, editor Sam Taylor became so overwhelmed that he refused to print any more letters–pro or con–on the incinerator issue, “at least until the County moves into the public hearing process in the early part of next year.”

Approval of the Initiative Petition would implement a new law that would restrict commercial uses in any Grand County zone. It said: “No zoning ordinance in Grand County shall allow: the incineration or burning of hazardous and/or toxic waste; the storage of toxic waste other than that created as a byproduct of local business or industry; the manufacture of toxins and viruses; the manufacture of synthetic pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides; the manufacture of chemical or biological weapons.”

In early March, the commissioners announced that they’d put off any zone change on the Cisco incinerator site until after the election. Then in May they unanimously approved a heavy industrial zone for the land owned by CoWest with the exception of an incinerator, leaving that decision to the voters. What was that all about we wondered until, at that same meeting, Dean Norris was asked if he had any other plans for the I-2 zone. “Anything I can attract,” he replied. The implication was clear—if CoWest failed to secure the right to build its incinerator, there were all kinds of other nasty things that could be placed in an I-2 zone. Jimmie Walker read the list of uses and it was downright scary.

With heavy media coverage from Salt Lake City and Grand Junction, television viewers watched Jayne Dillon bolt over a table to present Commissioner Walker with a letter from a Salt Lake attorney who believed the commission’s actions were illegal. A weary Jimmie Walker replied, “I’m going to assume we acted legally unless told otherwise by a judge or jury.”

As Election Day approached, Grand County was wound as tightly as a Warn winch. Coffee shop conversations were tense and animated, but as November 8th approached, supporters of the initiative to stop the incinerator were feeling confident and the commissioners were beginning to look like besieged and outnumbered defenders of a lost cause. Still, with Moab’s long history of mining and conservative politics, no one could be sure of the outcome.

The polls closed at 7 pm and Grand County residents were glued to their television sets. But in Moab, there was no “live” local news. Thousands of us were staring instead at the Channel 6 weather scanner, waiting for the updates. Channel 6 news director Ken Davey, the “Dean of the Moab Press Corps,” would videotape himself at the courthouse, reading the latest tallies. Then he’d pop the cassette from the recorder and sprint down Main Street to the studio and play the slightly delayed video.

Early on, a trend became evident–the incinerator was toast. By an ever-widening margin, Grand County voted in favor of the initiative and soundly defeated the project, ultimately by a margin of almost 2 to 1. Most remarkable was the turnout itself–more than 80% of all registered voters went to the polls on November 8, 1988; it was a record then, and we have rarely come close since.

The incinerator issue died on November 8, 1988 and no one has ever seriously considered a similar project for Grand County since. The statistics that came out of that election are still remarkable, because the vote was so free of an ideological bent. While almost two-thirds of the population opposed the incinerator, in the presidential election, Dukakis took a beating from the Republican George Bush. So liberal versus conservative, Democrat versus Republican didn’t play a pivotal role; instead, it was about our quality of life here, and toxic waste incinerators did not sound like an enhancement.

For Walker, Zimmerman and Knutson, they found themselves cast as the Darth Vader Trio to many of us in 1988, but it was hardly fair. None of them stood to profit personally from CoWest; coming from lifetimes in the extractive industries, the incinerator seemed like a quick way to increase the tax base in a depressed county on the verge of blowing away like so much dead tumbleweed. Opponents of the incinerator celebrated. Had a new day dawned in Moab and Grand County? We all hoped and dreamed that perhaps we really could re-define our community and create something new and different. Something to be proud of.

The “winners” and “losers” alike put the election behind them and moved on with their lives. But the question still remained: How do we make a living in Grand County, Utah? A year before the referendum, in November 1987, the Times-Independent ran a small story in its second section. The title of the article was, “Mountain biking in SE Utah is becoming a popular sport.” Hardly anybody took it seriously.

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

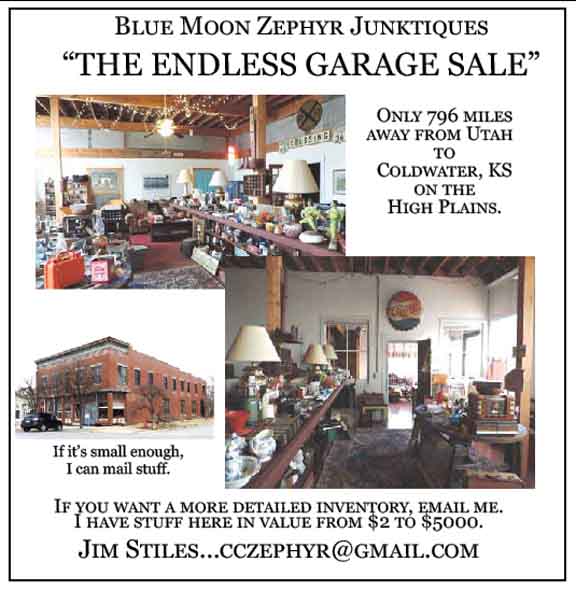

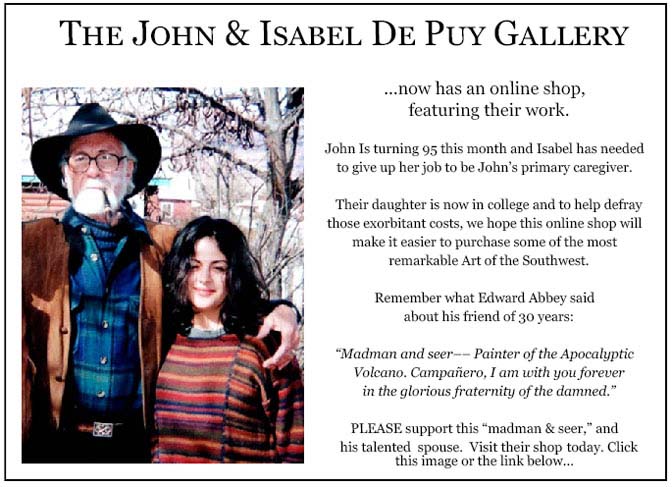

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

And once more, now that you’ve read the latest Zephyr Extra and waded through the ads, please take a minute to comment. Thanks for your support…. Jim Stiles

As Greg Rolie sang on the debut Santana album, “hope yer feelin’ better”. As for article… ah, the 80s. It was a golden moment here in the southwest, before the hordes appeared. Are they charging for timed-entry reservations yet to get into town itself yet?

Just shows what power the citizenry has if it looks into all the facts of a matter!! Nevada did a similar vote when nuclear waste was proposed here for storage. We’d already learned that all the safety talk about atomic blasts was not exactly honest!

Great story but I loved the photo of the ’80s bikers taken before Moab required mandatory Spandex for bikers.

Just ordered the book, from a Goodwill Store in Kansas! Thanks Jim as always.

Hey Jim. Glad you got over whatever “crud” you had. I visited Moab for the first time in October 1986. Perhaps I was a bit naive (or simply not knowledgeable about the closing of Atlas and the effect it had), but I found a cute canyon town that seemed to have life around it. I drove to Arches, then I signed up for a Jeep tour with Tag-a-long Tours to Canyonlands to go see the Colorado River Overlook and to drive partway up Salt Creek (both in the Needles District). I fell in love with the area over those two days. I returned in October 1987 for four days, taking hikes (Confluence Overlook and Chesler Park) and another Jeep tour (Island in the Sky, Shafer Trail). Back then, I was the only person on the trail in Chesler Park; it was glorious! But I came back a few years later to Chesler Park, and there were several hikers then then. I guess Moab and the Canyonlands area had gotten “discovered” by then. I bet if I returned to Moab today, it would be like visiting a completely different city, and I don’t think I’d like it as well. Thank you for sharing this chapter from your book. I look forward to reading more of them.

Poor Moab. I first laid eyes on the town in 1979, when I visited a friend during his first NPS gig as a seasonal ranger at Canyonlands. That trip included a day tour around the White Rim Road in my plain vanilla CJ5, followed by a detour to Grand Junction in my friend’s Ford Maverick to get my Jeep radiator repaired.

Through the 80s I visited occasionally, usually while going to or from my field research area in the Swell, in pursuit of a PhD in geology at the U of A. Moab was still struggling and funky. I was only peripherally aware of local issues, and I still took for granted the mostly empty and quiet nature of the western US, at least away from the coast and the big cities.

By the 90s Moab was a Destination. We began to think of the tourist crowds as hordes–if only we knew what was to come. I was often in Moab again, for geology field research and to lead classes and training groups. That continued for the next 3 decades, and every time I bitched about the crowds, and the rules, and the loss of simpler ways. And I started to play a game called “How Many New Hotels Since Last Time”.

Jim has written much more eloquently (and angrily) about the corruption that industrial tourism brings, driven by a fantasy of curated near-wilderness experience, shared by groups of thousands at a time. To be fair, those who sought a viable life in western towns, without either tourism or industry, also indulged in fantasy. Maybe the farmers and ranchers had the only sustainable vision. If only Moab and other towns could figure out how to sell things that customers do not want to buy on-site.

BTW, Jim, I treasure my copy of Brave New West, but I will apologize for buying it used. At least I did get it in Moab, at the used book store that used to sit in the corner of the strip mall by McStiffs.

Great comment Bob. The only thing that gives me comfort now is that fertility rates are slowing all over the developed world. Below replacement level. People are rejecting the narrative. Won’t be pretty, but better than the alternative collapse scenario. That’s my version of hope…

An exceptionally engaging account of that time of transition in Moab. Your writing is greatly appreciated.