EDITORS NOTE: Since I rebooted The Zephyr in March 2022, as a once a week posting of the new “Blue Moon Extra,” I have mostly stayed away from politics and controversy. After over 30 years battling one contentious issue after another, I have decided to spend more of my time trying to remember the way The West was, instead of beating my head against a wall, trying to prevent it from becoming what it is destined to be, and honestly— what it…regrettably… already IS.

I was never the most articulate spokesperson here either. But Stacy Young is. Though he was born and raised in San Juan County, I didn’t get to know him until a few years ago. His brilliant series of Zephyr essays during the Bears Ears Debacle, did more to illuminate readers about these public lands issues, than any other writer today. Just to remind you what thoughtful, intelligent writing can look like, please take the time to read this contribution from Stacy. It first appeared in The Zephyr more than three years ago … Jim Stiles

AN EXCERPT FROM STACY YOUNG’S ‘SLOVENLY WILDERNESS’ SERIES.

“Environmentalists so often seem self-righteous, privileged, and arrogant because they so readily consent to identifying nature with play and making it by definition a place where leisured humans come only to visit and not to work, stay, or live. Thus environmentalists have much to say about nature and play and little to say about humans and work. And if the world were so cleanly divided between the domains of work and play, humans and nature, there would be no problem. Then environmentalists could patrol the borders and keep the categories clear. But the dualisms fail to hold; the boundaries are not so clear. And so environmentalists can seem an ecological Immigration and Naturalization Service, border agents in a socially dubious, morally ambiguous, and ultimately hopeless cause.“

Richard White, “Are You an Environmentalist or Do You Work for a Living?”

I sometimes refer to the institutional and cultural apparatus that defines contemporary, mainstream environmentalism as the Recreation-Industrial Complex (RIC). The sobriquet applies mainly to the overlapping worlds of environmental NGOs, philanthrocapitalism, and Big Rec, but it is not limited to that. Over the past few decades, this economic and social ecosystem has quietly become a major base of power in America, but it has received precious little critical attention, especially within the environmental movement itself. Consider this shaggy collection of musings a few steps down that rabbit hole.

To pick a point of beginning, mainstream environmentalism has been an elitist project since at least the invention and popularization of the national park wilderness ideal about a century ago. National parks may or may not be America’s best idea but, contra Stegner, they are not “absolutely democratic.” Far from it. Mark David Spence recounts the most egregious departure from liberal ideals when he details how the establishment of national parks was impossible without the forced removal of indigenous people from the land they had occupied for generations. To preserve wilderness, as Spence puts it, it was first necessary to create it.

What’s worse is that indigenous dispossession was not an unfortunate, accidental consequence of the creation of national parks, but an entirely intentional outcome and the logical corollary of the worldview of the men who championed this new definition of wilderness. Old-money elites like Teddy Roosevelt saw themselves reflected in the trophy megafauna they hunted. Wilderness, in their view, was a romantic representation of an aristocratic American Ideal they perceived as threatened by the emerging class of gauche, new-money robber barons, from one side, and new waves of swarthy immigrants, from the other. The shameful reality, in fact, is that the park movement shared considerable intellectual DNA with the eugenics movement. It is hard to imagine a more anti-democratic set of values.

The point of reciting such historical lowlights is not to measure men long dead against the yardstick of present-day sensibilities nor to tar modern environmentalists simply by association with this appalling heritage. Obviously, environmentalism looks markedly different today than it did in Teddy Roosevelt’s era. Rather, there are two intended points.

The first is simply to establish that woke-washing the mythology of the national park ideal requires considerable historical airbrushing if not outright revisionism. Nature has many possible meanings and those which are most dominant in mainstream American environmentalism have a particular cultural etymology and specific identifiable features, not all of which are admirable. One enduring feature of the movement is an elitism that has evolved in its particulars with time, but retains a general and pernicious hold on public discourse about nature and the environment.

The second purpose in recounting this history is simply to provide a more acute lens for critical reflection; perhaps considering the uglier aspects of environmentalism’s cultural and intellectual foundations will better equip us to demythologize contemporary environmentalisms, including the powerful, mainstream types of which I tend to be critical.

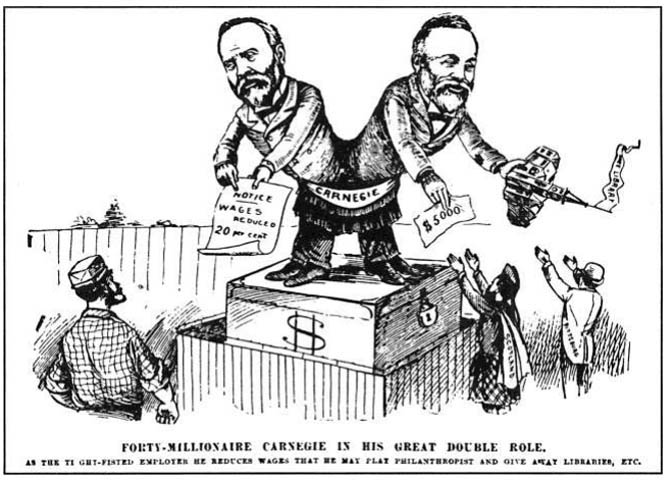

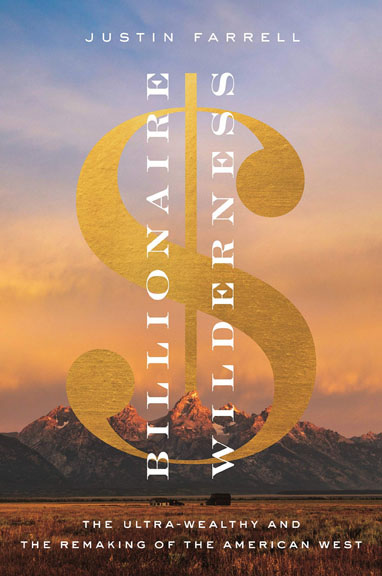

Attitudes about philanthrocapitalism have also evolved significantly in the past century, and this shift also features prominently in contemporary environmentalism. Teddy Roosevelt said of the philanthropy of the same new-money robber barons he viewed as threats to civic life and the American aristocracy: “No amount of charity in spending such fortunes can compensate in any way for the misconduct in acquiring them.”

Such an opinion is out of step with today’s conventional wisdom, which more closely aligns with Andrew Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth. But while today’s gilded giving is almost universally well received, there are skeptics here and there. Among the more prominent critics is Anand Giridharadas, the author of Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. Giridharadas coins the term MarketWorld to describe modern philanthrocapitalism:

“MarketWorld is an ascendant power elite that is defined by the concurrent drives to do well and do good, to change the world while also profiting from the status quo. It consists of enlightened businesspeople and their collaborators in the worlds of charity, academia, media, government, and think tanks. It has its own thinkers, whom it calls thought leaders, its own language, and even its own territory…

“These elites believe and promote the idea that social change should be pursued principally through the free market and voluntary action, not public life and the law and the reform of the systems that people share in common; that it should be supervised by the winners of capitalism and their allies, and not be antagonistic to their needs; and that the biggest beneficiaries of the status quo should play a leading role in the status quo’s reform.“

This sounds a lot like the state of affairs in contemporary environmentalism to me. To pick just one specific example, the board of SUWA alone manages to be well-represented by pretty much every category of elite listed by Giridharadas. Academics, media professionals, billionaire philanthrocapitalists? Check, check, and check. Likewise, the process of change and the set of acceptable solutions pursued by the likes of SUWA are of a predictable, narrow kind developed and supervised these elites.

“So what,” you may ask. What’s the harm if the rich want to underwrite green causes? I think there are (at least) two broad types of problems.

First and perhaps most obvious is the risk that the influence of big money will bend the agenda of environmentalism to accommodate donors’ business interests, or at least will make it impossible to be sure that this does not happen. Giridharadas, who is a gifted aphorist, has said that, for many MarketWorlders, making a difference is the wingman of making a killing. This problem especially applies to the many big money environmental donors who acquire their fortunes from unambiguously dirty businesses.

Even putting aside direct conflict-of-interest problems, it’s hard to fully swallow the argument that spending lavishly on environmental causes actually offsets the accumulation of enormous wealth through ethically or environmentally questionable means.

A related and similarly dubious rationale frequently offered by green NGOs for courting the patronage of the 1% boils down to a belief that it takes a good guy with a fat wallet to stop a bad guy with a fat wallet.

In any case, no matter how one thinks about these questions and contradictions, it is undeniable that mainstream environmentalism studiously avoids confronting them, and, in doing so, perpetuates an ethos which, as Giridharadas puts it, asks the wealthy to do more good, but almost never asks them to do less harm.

A second set of problems with today’s environmental philanthrocapitalism is perhaps more subtle, but also more certain: when the elite define environmentalism, they don’t just choose and frame what counts as a problem, along with the range of acceptable solutions to that problem, they also inevitably erase alternative, competing forms of environmentalism that may better square with the lived experience of the relatively powerless.

In a paper titled Powerful environmentalisms: conservation, celebrity and capitalism, Dan Brockington points out that it is often a fallacy to think of mainstream environmentalism as a weak David locked in battle with the powerful Goliaths of industry and goes on to describe two types of environmentalism.

The first represented by the conservation interests of wealthy people in the developed world who fund the work of the big conservation NGOs (or BINGOs). He asserts that the global growth of protected areas is driven by the demand for the pristine nature they provide. Such environments provide the “authentic unspoilt nature [people] wish to consume on their holidays.”

The second environmentalism Brockington describes is rooted in the services such environments provide to the rural poor: the harvest of wild foods, fuelwood collection, building materials etc. He suggests these two environmentalisms are in conflict, as evidenced by the on-going creation of protected areas, often driven by the agenda of the BINGOs, which can lead to physical and/or economic displacement.

Brockington asserts that the “Western wilderness ethic, which values pristine lands untouched and uninfluenced by people is not compatible with local environmentalisms. The inequitable power relations between local environmentalisms of the South and the well-financed Northern BINGOs often result in the marginalization of the former.

Brockington’s assessment seems right to me: environmentalism, as it is commonly understood in the affluent west, is synonymous with the accumulation and projection of power. The marginalization or erasure of entirely different forms of environmentalism, including the kind Brockington describes as most relevant to the rural poor, is one major consequence. Another is that, despite having an intimate connection with the environment in which their lives are embedded, few generational rural residents seem to self-identify as environmentalists. Maybe that’s because the very term “environmentalism” has little meaning to them and even less salience.

Brockington’s distinction between largely invisible local environmentalisms and the elite environmentalisms represented by powerful, well-financed NGOs also maps quite nicely onto the sociological concept of place attachment, which features prominently, if only implicitly, in Richard White’s influential essay from two decades ago titled “Are You an Environmentalist or Do You Work for a Living?”. In the paper, White argues that mainstream environmentalism’s hostility toward almost all types of work in nature has (at least) two negative consequences.

First, it negates the legitimate and profound place attachment many people form with their local environment through work of the kind which is alien or even repugnant to most self-identified environmentalists. At a minimum, this represents an enormous blind spot for many mainstream environmentalists, but what’s worse is that this hostility toward work in nature is often synonymous with disdain for workers in nature.

A second negative consequence, White argues, is that the failure of environmentalists “to examine and claim work within nature” cedes valuable cultural terrain to a wise-use movement that “confuses real work with invented property rights” and “perverts the legitimate concerns of rural people with maintaining ways of life and getting decent returns on their labor into the special “right” of large property holders and corporations to hold the natural world hostage to their economic gain.”

In this articulation, White finds the narrow strip of ground between positions which either are openly hostile to all work (and workers) in nature or which romanticize certain forms of archaic work, especially when that work is performed by poor, exotic people, or which implicitly shill for large-scale industrial exploitation. It’s a level of nuance that is almost entirely absent in mainstream environmental discourse.

The concept of place attachment is also explicitly referenced by Ethan Linck in his noteworthy essay in High Country News from two years ago in which he grapples with the common assumption that a constructive sort of environmentalism inevitably follows from the pursuit of certain forms of outdoor recreation.

In the essay, Linck observes that while outdoor recreation may certainly be worthwhile on its own terms, the particular kind of so-called environmentalism promoted by Big Rec frequently tends toward the self-serving: “there’s suggestive evidence that while the outdoor recreation industry is willing to take a public stand for wild places — to pledge its commitment to conservation as a political badge — it remains unwilling to pay for that commitment on any terms but its own.”

****

I would go a step further. At its best, spending time at play or leisure in wild places can lead to meaningful place attachment, which may then center a grounded and useful set of values around conservation and the environment. However, at its worst, Big Rec cultivates nothing more than a highly mediated sort of synthetic attachment, which is not actually to place at all, but merely to an idea of place. This sort of environmentalism amounts to little more than a social affectation which leans heavily, in Abbey’s formulation, on “sly art and eco porn.”

Of course, it takes more than the financial capital of billionaire benefactors to make mainstream environmentalism as powerful as it is. To really move a culture also takes cultural capital. Lots and lots of cultural capital.

It takes a legion of urban professionals in their ubiquitous Better Sweater Vests. Environmental philanthrocapitalism isn’t just for the 1%, after all. It’s also for the 9.9%.

It takes middle-class, suburban, latte-liberals stuck in their Subarus in traffic between Boulder and Denver right now.

It takes the rest of Anand Giridharadas’s MarketWorld ecosystem, “the collaborators in the worlds of charity, academia, media, government, and think tanks.”

It takes the symbiosis of all these classes of people with the lifestyle brands through which they signal their green bona fides.

*****

And, last but far from least, it takes the crunchified hypebeast energy manufactured by these same lifestyle brands and their small army of professional neo-Beatnik ambassadors, along with the self-employed, self-conscious and photogenic social-media influencers from the steadily growing ranks of downwardly-mobile van-lifers and trust-funders.

To illustrate the media’s place in the Recreation-Industrial Complex, I think I’ll pick on Outside as a bundler of the market forces and shifting demographics behind environmentalistic power.

Every so often, Outside publishes something that ought to call into question the very orthodoxy of the Recreation-Industrial Complex of which Outside is essentially the house organ. Yet somehow these articles never amount to more than a glancing critique. A recent offering in the genre, written by Mark Sundeen, considers the state of affairs in canyon country and, predictably, finds Utah’s Mighty Five campaign to be the proximate cause of the runaway tourism affecting Moab and beyond.

To be clear, I think the weight of the piece is relatively good, and, true to Outside form, it is exceedingly well-written. There is also a side of me that gives credit for courage anytime something is published that even obliquely implicates the publisher or its advertisers. Still, a lot of it is, at best, puzzling.

For example, Sundeen writes: “We all bear some responsibility in changing this place. Yet we don’t bear it quite evenly. Market forces and shifting demographics and social media don’t deserve the same sort of scrutiny as taxpayer-funded programs like the Office of Tourism.”

Why does the state’s Office of Tourism deserve more scrutiny than market forces and shifting demographics and social media? The answer isn’t obvious on its face and Sundeen never really says.

If the Utah State University study cited in the article is approximately right, about 5% of visitation to Utah’s national parks is attributable to the state’s Mighty Five advertising, and yet it gets about 95% of the critical attention in the article. Anecdotally, this rough inversion of the blame-to-attention ratio is pretty typical when the topic of canyon country tourism comes up, and while this strategy may simplify an argument, it does not actually illuminate much.

For one thing, marketing only really works if it is tonally on point; great marketing arguably understands its audience better than its audience even understands itself. So our contemporary cultural context is in effect the canvas on which a tourism office paints. If Utah’s marketing has been effective, it is only because it has expertly met its moment.

This focus on Utah’s Office of Tourism also completely sidesteps both the qualitative similarity and quantitative impact of the marketing of canyon country by Outside and its many Big Rec advertisers.

*****

More pointedly, waving off larger social and economic forces is not a neutral rhetorical move. It is in fact a quite consequential editorial choice and, for Outside, an awfully convenient one. The magazine’s media kit credibly claims to offer advertisers “the most sought-after demographics in all of publishing,” based on a large, loyal, and influential audience that follows the brand across a full spectrum of media platforms and brings with it an average household income north of $100,000. It is an audience that apparently supports ad rates of up to $200,000+ for a single two-page color spread in the magazine. Given this profile, it’s no wonder Outside would prefer to steer clear of a more searching examination of the forces that are actually operative in the postindustrial commodification of nature, the neoliberalization of environmentalism as a movement, and the steady expansion of the thing we shorthand as the New West.

I guess my criticism of Outside here is that focusing blame on capitalistic Republicans (as opposed to the Democratic kind) and a state tourism office for what’s happening across southern Utah is just so easy and formulaic. And, you know, fine. Except for this: what’s happening in Moab and beyond is just one small manifestation of a comprehensive, self-reinforcing system — of which Outside is more than a bit player — which I’m calling the Recreation-Industrial Complex. And this system is inextricable from a larger system, which is usually called neoliberalism or late-stage capitalism. And brushing off fundamental, troubling aspects of these systems with a passing yada-yada in order to fire a few more rounds at the usual soft targets actually prevents an honest reckoning with the roots of the problem.

One fascinating thing about these sorts of articles is how they fit within the practice of contemporary mainstream media writ large. Business-model success for outlets like Outside seems to be based on a journalistic presentation intended to occasionally make the magazine’s affluent, professional-managerial audience sufficiently uncomfortable that they are reassured of the publication’s rigor and objectivity, but this discomfort must always remain subordinate to a political thesis that confirms all the biases of the same audience. A good limousine liberal is always down for a bit of self-flagellation, but only a bit.

So we get, for example, writers for publications like the New York Times going on safari among the white working class in order to reassure its readers that, yes, globalization has brought hard times to many parts of the country, but Donald Trump’s election was mostly due to, you guessed it, bigotry. And we get writers for Outside checking in on the creeping tide of tourism in Utah’s canyon country in order to reassure its readers that there’s no problem afoot, and even if there is, it’s mostly due to, you guessed it, unscrupulous Republicans. Complex phenomena are flattened and reduced, and neither the publication nor its audience is ever truly complicit.

Of course, whether this elite-coddling editorial approach is done consciously or is simply the expression of a specific social milieu; whether it is actually as subtle as its practitioners suppose; and whether the ostensible subtlety counts as an improvement over expressly political media, are all open questions. In any case, this narrative recipe strikes me as particularly apt for Outside and its audience. Who, after all, embodies the strand of lifestyle-leftism that weds play as performative suffering with unimpeachable good taste more fully than the modern endurance sport athlete-cum-nature connoisseur?

For what it’s worth, I say all this as someone who fully occupies the bullseye of Outside’s target audience. Epic trail running adventures, Rapha, rustic farm-to-table dining, parkitecture? I’m an overeducated member of the professional-managerial class who is a sucker for all of it.

Curious about how the piece landed with Outside’s audience, I headed over to the magazine’s Facebook page and found the thread on Sundeen’s article tucked safely among links to a van makeover piece (“Take Your Van from Dirtbag to Dream Home”) and a listicle on “America’s 25 Most Accessible — and Beautiful — Trails.” The comments, much like the article itself, consisted mainly of nostalgia for the way southern Utah used to be and anecdotes about how bad or not-bad the problem really is, with a sprinkling of more critically penetrating and uncomfortable points mixed in. Based on the comment count and emoji voting, “engagement” with the piece was high, yet no one seemed particularly stirred up. So maybe Outside’s approach is in fact as effectively subtle as it aspires to be. Then again, maybe Outside’s audience is simply, on average, quite a bit more smug and credulous than they suppose themselves to be.

*****

To be sure, the contemporary classism of mainstream environmentalism exists in its mature, modern form thanks only in part to causes traceable to the concrete actions of identifiable actors. To take a much broader view, it is but one consequence of a financialized global economy that has sown deindustrialization and severe wealth inequality across many affluent nations like the U.S. while producing modern-ish industrial economies across Asia and parts of the global south. The New West represents a form of gentrification, and gentrification can be reasonably described as the spatial expression of economic inequality. It is only natural, in this view, for the massive inequality of our new gilded age to be expressing itself all over Moab and similar places.

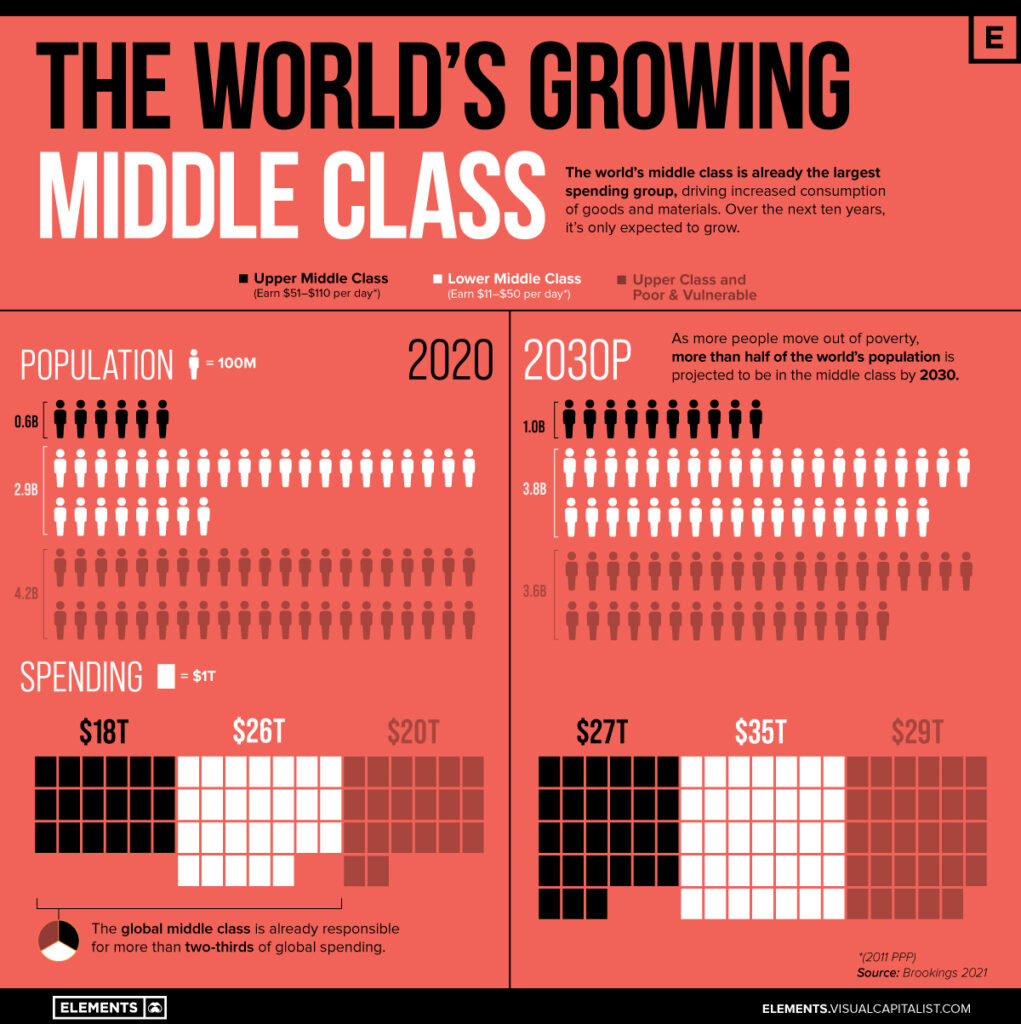

Although these underlying forces are properly understood as phenomena of late-stage capitalism, we are in some respects still very much at their beginning. The global middle class, which numbered about 3 billion people worldwide in 2015, is expected to increase by a whopping 67% to 5 billion by the year 2030. Such drastic reduction in human immiseration is obviously a wonderful trend, but is just as obviously a trend with enormous implications for resource consumption. Fearless prediction: the newly minted middle class is going to want more stuff and they are going to want to travel.

The social and environmental alienation caused by these macro forces will also almost certainly lead to further erasure of the grounded, local environmentalisms of rural residents in favor of the powerful, urban- and elite-centric environmentalism that is being stitched into our cultural fabric by the Recreation-Industrial Complex.

To borrow John Michael Greer’s distinction, these phenomena almost certainly do not represent a problem, for which there may be a solution, but a predicament, from which there is no escape. But while there may be no escape, all methods of coping are not equivalent. And it seems to me that better coping responses, even on a merely personal level, must be based on the truth of how we got here and about the nature of “here” itself.

I’ve suspected for some time now that if New West phenomena crossed national borders and were being imposed on powerless and exotic brown people rather than unsympathetic white people in rural America, we’d more readily recognize what’s happening in places like Utah’s canyon country as a sort of eco-colonialism.

What I mean by colonialism is the demonstrable social, economic, and political domination of long-time inhabitants of certain places by elite settlers and noninhabitants, mainly through the control of land. Contemporary mechanisms of colonial-ish control include structural and institutional forces like the sweeping authority over giant tracts of land retained by the federal government (or acquired by billionaires or NGOs), but especially such atomized, private-sector forces as tourism and the related processes of amenity migration and socioeconomic restructuring.

Underpinning the Recreation-Industrial Complex and putting the “eco” in this form of colonialism are a set of dominant social constructions of the meaning and value of nature, wilderness, and the rural along specifically greenwashed, postindustrial lines. William Cronon’s introductory essay to the Uncommon Ground anthology is a useful reference on this point.

I’m only providing Cronon’s definition or a short comment here, but the main idea of each concept is, I believe, at least superficially self-evident. Also self-evident in these concepts is a persistent elitist impulse and a stubborn dualism between humanity and nature. Consider that there is almost no trace on this list of the sort of “nature” that would be recognizable to unorthodox, place-based (non-identifying) environmentalists to whom this dualism is alien.

1. Nature as naive reality. “The sense that when we speak of the nature of something, we are describing its fundamental essence, what it really and truly is.” This is basically the Anecdote of the Jar paradox. Nature is a thing in itself and “nature” is also a social construct, and the common usage of the term is rarely self-conscious about any tension inherent in this difference.

2. Nature as a moral imperative. “The great attraction of nature for those who wish to ground their moral vision in external reality is precisely its capacity to take disputed values and make them seem innate, essential, eternal, non negotiable.”

3. Nature as Eden. A prominent subcategory of nature as a moral imperative. “(A) great many environmental controversies revolve around … “Edenic narratives,” in which an original pristine nature is lost through some culpable human act that results in environmental degradation and moral jeopardy … The myth of Eden describes a perfect landscape, a place so benign and beautiful and good that the imperative to preserve or restore it could be questioned only by those who ally themselves with evil.”

4. Nature as artifice (nature as self-conscious cultural construction). “Once we believe we know what nature ought to look like — once our vision of its ideal form becomes a moral or cultural imperative — we can remake it so completely that we become altogether indifferent or even hostile toward its prior condition.” Landscape architecture and similar human interventions, the best of which erase or at least obscure the work of the architect, are liberally employed all around us. The paradox is that this staged and airbrushed sort of nature unintentionally becomes idealized over native, untouched nature with all its warts.

5. Nature as virtual reality. Broadly, this refers to intermediated nature, whether the intermediary is digital or physical-corporate. Think Instagram, Patagonia, Sea World.

6. Nature as commodity. The obvious meaning of this concept relates to heavy industry and physical, tradable goods. The less obvious but perhaps more potent meaning in our postindustrial economic context relates to the ability of a particular idea of nature to be packaged as a consumable experience.

7. Nature as demonic other, nature as avenging angel, nature as the return of the repressed. This is the inversion of the Edenic narrative: “environmentalists so often seem drawn to prophecies of ecological doom that offer elaborate descriptions of the disasters that will soon occur because of our misdeeds against the earth.”

8. Nature as contested terrain. “On the one hand, people in Western cultures use the word “nature” to describe a universal reality, thereby implying that it is and must be common to all people. On the other hand, they also pour into that word all their most personal and culturally specific values: the essence of who they think they are, how and where they should live, what they believe to be good and beautiful, why people should act in certain ways.”

*****

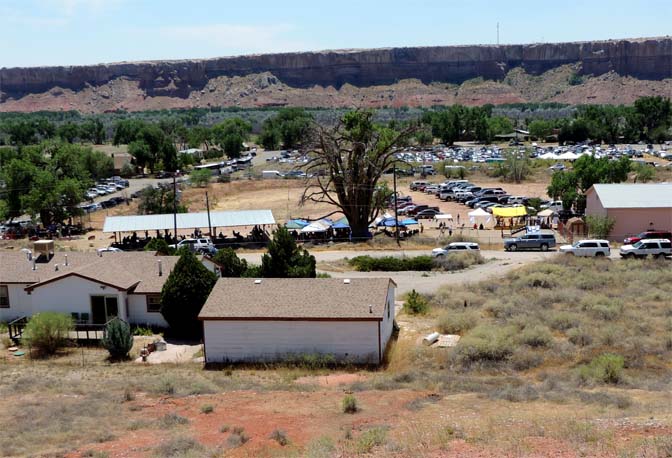

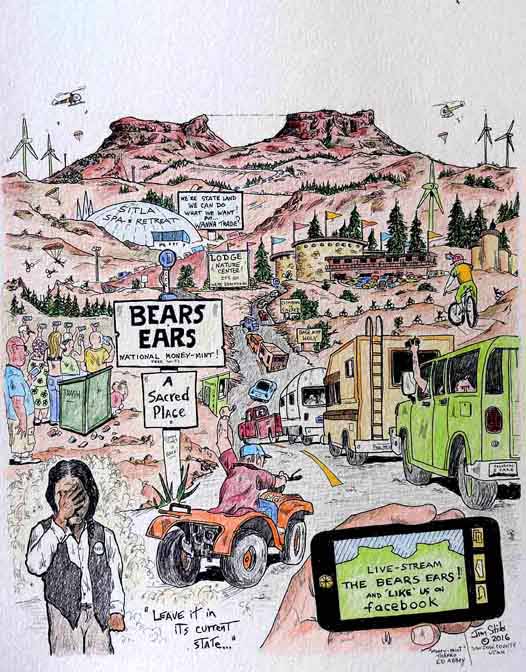

If there has ever been an instance in America that demonstrates better than the Bears Ears monument fight the ability of the Recreation-Industrial Complex to harness and project power, I’m not aware of it.

There’s no need to rehash all of the twists and turns in the saga; many thousands of words have already been published by the Zephyr documenting how the Bears Ears controversy was made. (To me, the best primer on the topic remains the one written by Jim Stiles even before the monument was designated.) I also assume, given the intelligence of the typical Zephyr reader, that there’s no need to exhaustively apply the conceptual framework outlined above to that recent history; I’m sure the connections are obvious. Still, I will highlight three points.

Bears Ears-as-Eden. An Edenic narrative permeates substantially all of the pro-monument message, from the Presidential Proclamation issued by Barack Obama to all the sly art and eco porn produced by Patagonia. The stakes of the morality tale are raised even higher than usual because the protagonist of this particular Edenic story is a noble savage. As questionable as both of these tropes are, the indigenous component is particularly complicated, in terms both of its actual, basic political economy and the Ecological Indian stereotype within America’s long, ugly, and tangled colonial history.

Bears Ears-as-commodity. To fortify an Edenic narrative that implies that only those who ally themselves with evil could oppose monument designation, advocates have dutifully rummaged around to find themselves a concrete villain or two. They have only ever managed to conjure a few paper tigers, but even these have been plenty to give the credulous the vapors. This was predictable and fairly boring. What has been more interesting to me is how effectively Big Rec has commodified the idea of Bears Ears for their consumers who had zero pre-existing awareness of the place, much less attachment to it. They have succeeded in turning political activism into a successful marketing strategy and even managed to find new life for the wise-users’ dubious language of invented property rights: The President Stole Your Land.

Erasure of Local, Place-Based Environmentalisms. Working in conceptual terrain adjacent to the sociological theory of place attachment, much of Wendell Berry’s creative energy and considerable wisdom has been devoted to pushing back against the scornful, divisive, and exploitative “southernization” of rural America by liberal urbanites. In The Unsettling of America, he writes:

“Generation after generation, those who intended to remain and prosper where they were have been dispossessed and driven out, or subverted and exploited where they were, by those who were carrying out some version of the search for El Dorado… They have always said what they destroyed was outdated, provincial, and contemptible…”If there is any law that has been consistently operative in American history, it is that the members of any established people or group or community sooner or later become ‘redskins’ — that is they become the designated victims of an utterly ruthless, officially sanctioned and subsidized exploitation…

”The first principle of the exploitive mind is to divide and conquer. And surely there has never been a people more ominously and painfully divided than we are — both against each other and against ourselves. Once the revolution of exploitation is underway, statesmanship and craftsmanship are replaced by salesmanship.”

This is the real cost of the way modern environmentalism is waged. As environmental MarketWorld elites flex their muscles through expensive lawsuits, university symposia, endless Op-Eds in fancy publications, and round-the-clock fundraising, complex, multifaceted issues are made ever dumber, more binary, and divisive. In the bargain, opportunities for an entirely different, more participative problem-solving paradigm are destroyed and alternative perspectives erased.

*****

Perhaps a good distillation of what is flattened by the Recreation-Industrial Complex steamroller and a fitting coda to this long and winding collection of thoughts is the testimony offered by Byron Clarke to Secretary Jewell’s monument delegation in 2016:

“I’ve grown up here my whole life. I’ve been hiking Bears Ears (since) before it was cool. I used to get up there and shine little mirrors down into Blanding and call home and say, ‘did you see that?’ I cut wood out there — I have two chainsaws and a truck, I’m one of those guys — for elderly Navajos. I take it down each winter — by February, they’re usually out.

“The evolution of national monuments is what concerns me. Canyon de Chelly is an example of this. 1928: ‘nothing will change…you’ll get your wood…you’ll get what you need…you’ll get everything you want.’ Other monuments across the country, 50 years later: ‘you’ll get what you need, nothing will change, we’re just protecting it.’ But it evolves. …

Testimony from Byron Clark:

“I’ve been down the canyons of Grand Gulch. I’ve been ranching — I put horses and cows in that corral that you looked at yesterday at that point by Peavine and Woodenshoe. My brother died at Hart’s Draw. Talking to Manuel Heart — he’s the (monument) resolution signer for the Ute tribe — I had lunch with him at the Kuchu restaurant in the casino over there last December. And what he said just cut me, ‘cuz he said, ‘it’s a nice place…never been out there.’ You’ve never been out to Woodenshoe? …

“It’s very easy to say ‘I’m protecting it’ in this way. That’s good, I want to protect it, too. Every time we look at the map and say ‘do we need all that, is this the right thing to do for it, is there unintended consequences’ we just get thrown out as people who don’t care about the land. And we do. I just want to let you know that — if we’re not in support of the monument, if we’re in support of (the Public Lands Initiative) — by God we care about it.“

Stacy Young was a regular contributor to the Zephyr for more than five years, and still plans new writing projects for The Zephyr, when he gets the time to do anything but work. I think Stacy is the most articulate and intelligent, and more than anything, the most honest contributor that I have had the honor to publish in The Zephyr.. He lives in Southwest Utah.

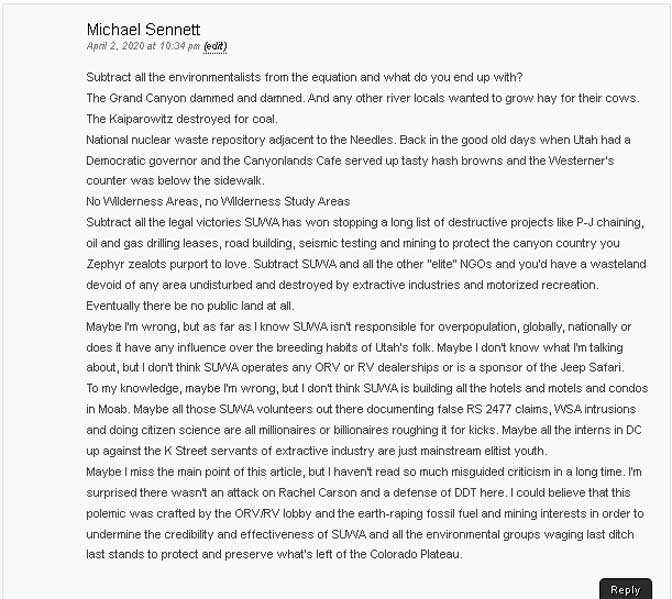

EDITOR’S NOTE: When I posted this story, over 3 1/2 years ago, we received several responses, a couple of them quite angry…they just didn’t get the point Stacy was trying to make. I have reformatted this page and I hope that more of you will reply as well, in the comments section below.

But first, here are screenshots of the most memorable comments from 2020

TO REPLY TO THESE SCREENSHOTS, YOU’LL STILL NEED TO SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM AND CREATE A NEW COMMENT. BE SURE TO MENTION WHICH OF THESE PRIVIOUS COMMENTS YOU ARE REFERRING TO…JS

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

Signed copies

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

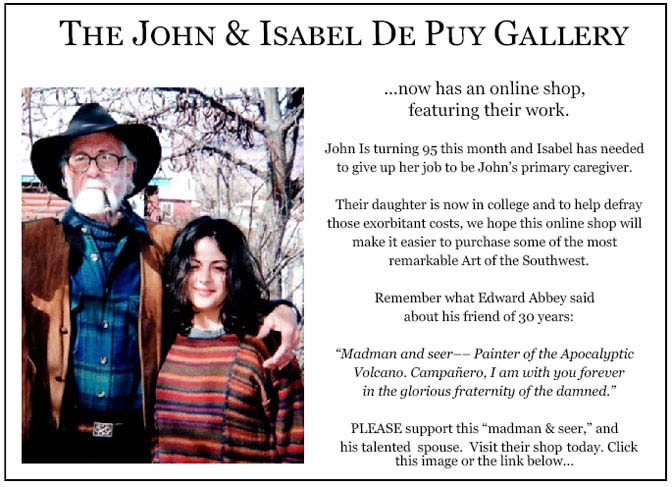

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

From a strictly personal point of view, I think there are some radical environmentalists who, like Al Gore, spout “save the land” and fly frequently on privately owned planes which use fuel! I feel the lack of allowing annual care given to forested areas has allowed the hideous fires which consume the un-removed underbrush and allow forests, not only of evergreens but ancient sahuaros and joshuas to be eradicated, never to resume their beauty in our lifetime. Recreationists trash the areas where they recreate, tear up the landscape. Farmers and ranchers fight this all year long.

Brilliant work. Stacy is certainly one of the most astute, well spoken and intelligent writers in our era. He has an ability to connect dots many cannot even comprehend. I find myself fascinated at the way he can see and describe what many of us can see, but can only clumsily try to explain.

I certainly hope at some point he’ll put his formidable skills to work and examine what I can see as the next phase of pseudo environmentalism throwing the “natives” off the land. This new method is to fully integrate the environmental organization “worker bees” into the government of these western rural communities. Elected offices, appointed offices on various boards and commissions or within the government.

This phenomena first came to light in the 2022 elections in se Utah, when a treasure trove of emails were obtained that showed beyond any reasonable doubt that SUWA was in fact dictating and running two Native American county commissioners in San Juan county. Telling them how to vote on any issue of interest to SUWA, preparing resolutions for them to further their takeover of the land. It was astonishing. Many of us had seen it for years, but to even suggest it put one in the “conspiracy” crowd. But the emails spoke for themselves.

SUWA had spun off a second non profit affiliate, the Rural Utah Project, that operated under the guise of Native American voter registration. Another clever cover to use, because of course, who can possibly be opposed to everyone being registered to vote who is eligible to vote. And it would of course be considered “racist” to even question the effort in regard to native Americans. It’s how they got the two commissioners in office that they were controlling.

And of course, here in Grand County we could see the same group of SUWA/RUP operators embedding deeply in Moab and Grand County government. On County Commissions, City Councils, Planning and Zoning commissions, and of course multiple direct hires in county and city government.

Fortunely those emails opened many peoples eyes, even those who may have supported the SUWA effort of land preservation and fighting the evil resource users. Not even they thought SUWA should be running our local governments. The two puppet San Juan county commissioners lost their elections, and some of the SUWA/RUP people and supporters were removed from office in Grand County.

We have a long ways to go to rid the west of this faux environmentalism and return management of our lands and resources to common sense groups of people who simply want solutions that work best for the most people.

I’m glad people like Stacy Young can so clearly see what is happening, and so eloquently write about it. I just wish we had more people like him.

As Walt Kelly (Pogo) said so well long ago “we have met the enemy, and he is us”

You’ve got that right, Tom Patton..

This is an excellent and eloquent piece. I just taught Cronon’s “The Trouble with Wilderness” essay and the intro to Uncommon Ground mentioned here, and I am glad to have been reminded of this piece by Stacy Young. I’ll give it to my students, for sure.

But a thing I’d love him to expand on, if he ever gets a chance, is his understanding of the “grounded”, “local environmentalism” to which he refers in positive terms. I just wonder if it isn’t idealized, or romanticized, in ways that echo the romanticization of wilderness one finds in the edenic narratives that Cronon criticizes. And I wonder, too, about the way in which the “work” that goes on in “nature” isn’t idealized as well. I’d love to hear his nuanced and intelligent investigation of those things. If I were to offer a critique of this essay–and one that is really based in admiration for it–is that for all of the criticism of binaries the essay articulates, isn’t there a new, rather simple binary created between “local environmentalism” and the Recreational-Industrial Complex?

Thank you for this intelligent piece.

I see a dominant mind-set in the notion that “the outdoors”, at least the areas that appeal in some way, should be only for visitation and play. Thus while some people praise preservation, they mostly do so with provisos that they still get to vacation, and sight-see, and recreate in the proper ways they enjoy. Aside: the noble class has just as much vitriol for those who recreate in improper ways as for those who might want to use the land for other things. That’s probably a reflection of the religious component of ideas about land.

Anyway, if the conditional preservation crowd has its way, I can see a future where large areas, including all of Utah outside a few metro areas, are managed as some type of “park”, with evidence of present and past undesired evil land uses obliterated, carefully curated experiences, and, of course, the commercial amenities desired by those on pilgrimage.

You hit the nail on the head…many have a vision of SW Utah as a vast N.P., where the moneyed recreate, and the locals serve them in the recreation industry. If your job is not in the recreation industry, it is probably “dirty” and you won’t be allowed to do it. It is elitism of a very pernicious sort.

The unavoidable, inescapable Future.

No, I’ve got a somewhat different view of this piece.

I get the drift of Mr. Young’s allegations, and, yes, there are “elitist” environmentalists out there; I’ve met a few. But as with all assemblages of people, there is going to be variety, some you will like and others you will dislike. And I fully agree with the early-on charge of how parks and wildernesses were once the domain of indigenous people.

However, I find the article to a very long castigation of people and groups who indeed care about the future and fate of lands and resources in this part of the world. It makes very broad elegant wordy assumptions about the people and causes which paints an overly one-sided brushstroke over the movement to preserve places like Bears Ears. I’ve spent a fair amount of time in that region, and can attest that there are people, including those of native ancestry, not fitting the elitist recreationist image, whatever that is, who see Bears Ears as an important part of their lives.

And, as I see it, there are several reasons that groups like SUWA exist. Yes, Jim, I too would like to go back to those road trips of the 1950s, breathe the dust of Hwy 95, gaze at the flowing Colorado from Chaffin’s ferry, and poke around the canyons of Elk Ridge with nobody else around. There was little need for a SUWA then. But industry has changed. Motorized recreation has changed. Archeological features are being diminished. And, like it or not, the entire area has become a mecca for visitation. And not all uses are compatible with each other. So, while I do think some preservation campaigns go too far, I find that to be at the least equally true for the development campaigns.

I appreciate that there are leaders who raise there voices against the tide.

One side note: While I can’t predict the future, it seems to me that the nature of current use on Cedar Mesa and Elk Ridge, all within Bears Ears N. M., seems to be balanced. Cattle still graze. 4WD “Jeep” roads are plentiful. Pine nuts are harvested. And, there are also wildernesses with hiking trails or no trails at all.

My two cents.

Nothing I do or write, or anything that Stacy Young has written here, or in other Zephyr essays, I’d motivated by the idea of returning to “the way it was.”

We’re just documenting the recent history of rural utah and the rural west. The mainstream environmental movement wants to create a one economy west —- tourism and a strong amenities presence —— to the exclusion of all others.

The truth is, ALL industries are “extractive.” SUWA condemns all forms of energy production. Except renewables. But they condemn the mining of the very minerals there are required to make renewables work.

And most odious of all, as I’ve been reporting for 20 years. Some of the wealthiest industrialists and private equity barons finance these “grassroots” groups. Fifteen years ago, I wrote an essay for High Country News that ran in papers around the west. SUWa had $5 million in net assets but spent nothing on the environmental impacts of industrial tourism. Their response could not have been more toxic or disingenuous.

Nothing changed. And all these years later, SUWAs net worth exceeds $20 million. And they’re not “saving” anything.

“Burn down the mission

If we’re going to stay alive

Let the black smoke rise up to heaven

Let the flame torch light the sky

Behind four walls of stone the rich man sleeps

It’stime we put the flame torch to his keep”

-Bernie Taupin, Burn Down the Mission

The Lesson of ESPANOLA, NEW MEXICO: still unconquered…

For those who know Espanola, you know what I mean. As badly as northern New Mexico has been overrun by the enviro-posers from Kali, Espanola still abides. They’re not rich, certainly not like the Santa Fe/Los Alamos petite bourgosie. Sometimes, it’s not pretty or nice, but it is effective. How did the Italians and Irish hang onto their neighborhoods in the big eastern cities(Southie or Queens)? The Ownership Caste fears and avoids Espanola. They have their own cops and prosecutors. People were afraid of Big Water until Alex Joseph died. Now, they’re even making moves on Glen Canyon City. You’d think piles of dead cars composting in the desert sun for 50 years would keep them away, but it’s an infestation worse than bed bugs. In a just world, they should be afraid to take communities away from the working class. There should be consequences and repercussions. My own views are somewhere along the continuum between Kurt Vonnegut, Ed Abbey, Doc Kacinsky and the James-Younger LLC.

The unavoidable, inescapable Future.

Thank you for your work Stacy. RIC continues ongoing attempts to push legislation allowing unlimited commercial recreation on Federal lands found in bills like the America Outdoors Recreation Act.

Try being a “conservative” and critiquing the recreational industrial complex. I look at Patagonia, REI, and Outside monetizing the outdoors, and see smug self serving hypocrites. I was a latecomer to Cedar Mesa, but before “Bears Ears,” and firmly believe the NM designation will just drive up visitation, further degrading the area, and offset and supposed benefits of NM designation. And what good is rules if the money to enforce the rules is never provided? Ever see a backcountry ranger there, in field, patrolling to protect sites? I never have. It is some comfort to know I am not the only crank.

Thanks for the read. I enjoyed the bit about different meanings or definitions of “nature”; it helps put the different voices and politics into perspective as the battle for land use/designation wages on.