July 15, 1913 – December 11, 1998

On December 11, 1998, twenty-five years ago today, my friend Herb Ringer passed away in Fallon, Nevada. He was 85 years old. His health had been failing for a few years. In 1994, Herb was forced to give up driving — the greatest joy of his life — when he was diagnosed with a rapidly deteriorating case of macular degeneration. I had met up with him that summer at a high mountain lake above Crested Butte, Colorado. Earlier that week, an optometrist in Salida had diagnosed his condition and warned Herb that he needed to head home to Fallon immediately. Herb took the news stoically, maybe better than I did, and he left for Fallon the next day.

For almost 15 years, Herb had been coming to Arches and Moab to visit me. Now it was my turn to make regular visits to see Herb.

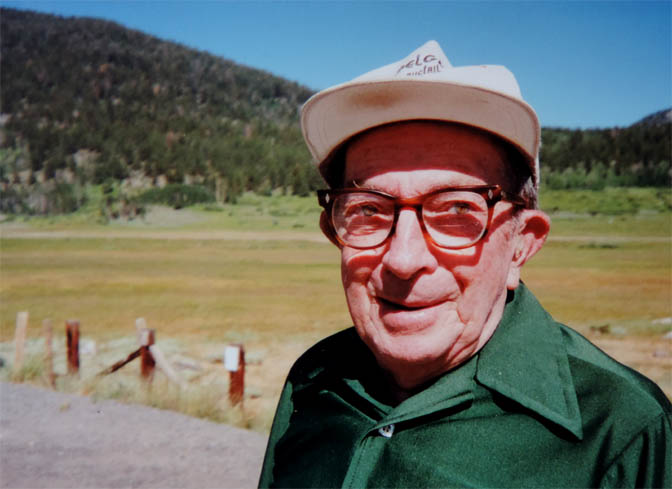

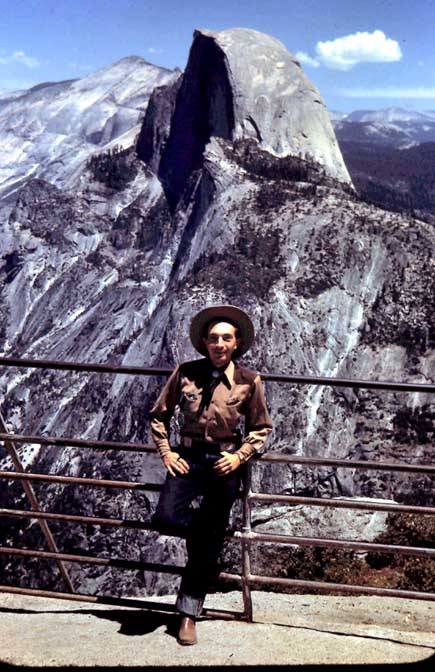

I’ve reported the facts of his life many times and had the opportunity to share his many talents. Most Zephyr readers are familiar with Herb’s magnificent color transparencies of the West, going back as far as 1946. And in the years before Kodachrome was invented, he was just as much a master of black and white photography. You can access many of those stories and images here. But this story is personal; it’s more about our friendship than his special artistic talents, though both are forever intertwined. I’d like to tell you more about Herb Ringer, the good-hearted, decent man and loyal friend that he became to me. We were connected in a way that I have rarely experienced. Herb once said, “You’re the son I never had.” The feeling was mutual.

*****

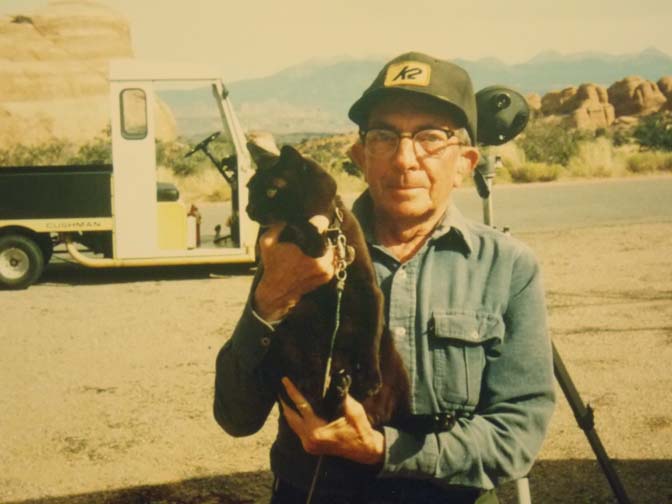

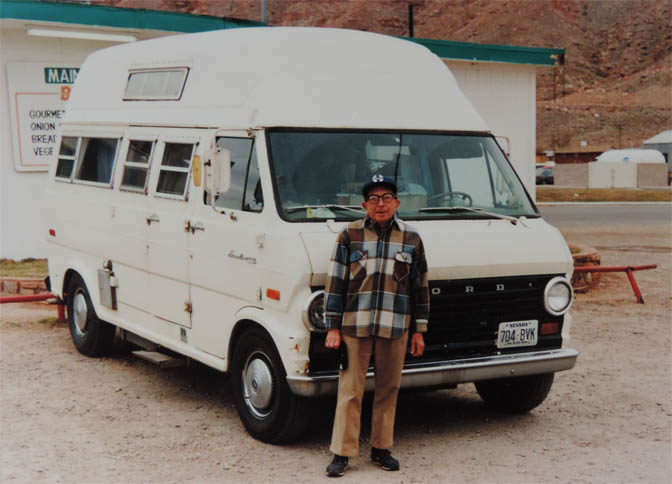

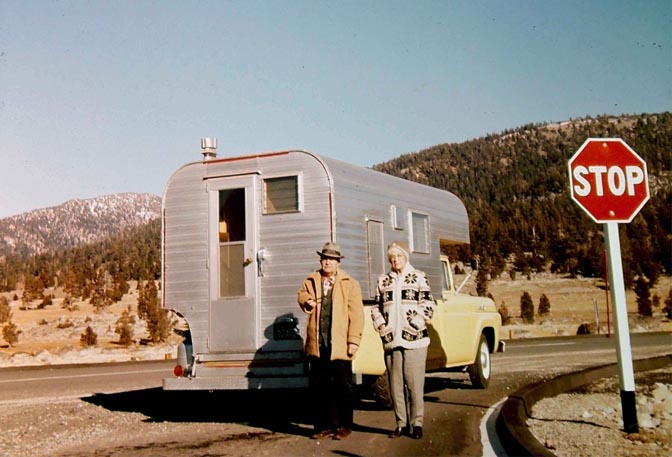

I met Herb in the summer of 1981, and at the time, would never have guessed that I’d still be writing about and remembering his role in my life, more than 40 years later.. I was the campground ranger at Arches National Park. In those days, we walked site to site to collect the daily fee. To this day, some of the best friends I’ve ever known were born during those personal contacts. I still remember walking up to his white Ford Econoline camper van at site #22…there was Herb. He was sitting in a lawn chair in the shade of a juniper tree; beside him, on a leash, was a Burmese cat that I later learned he called Namtu.

I’m on the short side myself, but when he stood up to greet me, I realized that Herb was barely five feet tall. He had the thickest head of hair I’d ever seen and though he was in his 70s, he had not yet gone gray. Best of all, he had the warmest smile. He’d smack me if he were still here, but he had the face of a cherubic angel. From the moment we shook hands, I could feel the kindness that emanated from all sixty inches of him. He showed me his Golden Age card and handed me a buck-fifty—the going camp fee in 1981. We spoke for just a couple minutes that first night, but by Day #3, I looked forward to our evening chats.

We started sharing information about our lives. He told me that he’d come West from New Jersey in the late 1930s. Even then, I had dreamed of what the West must have been like in that last decade before World War II. . I wanted to know more. It already felt like the beginning of a long friendship.

Finally by the third day, we were trading the more personal details of our lives. Herb asked me if I was married and had a family. I hesitated a bit, looked at him sadly, and shook my head.

“No,” I told him, “I’m actually going through a divorce this summer. It’s been pretty rough.”

Suddenly the smile vanished from his face and his eyes filled with tears. He took a step toward me and placed his left arm on my shoulder. With his right hand, he gripped mine. He wiped the tears from his eyes and explained…

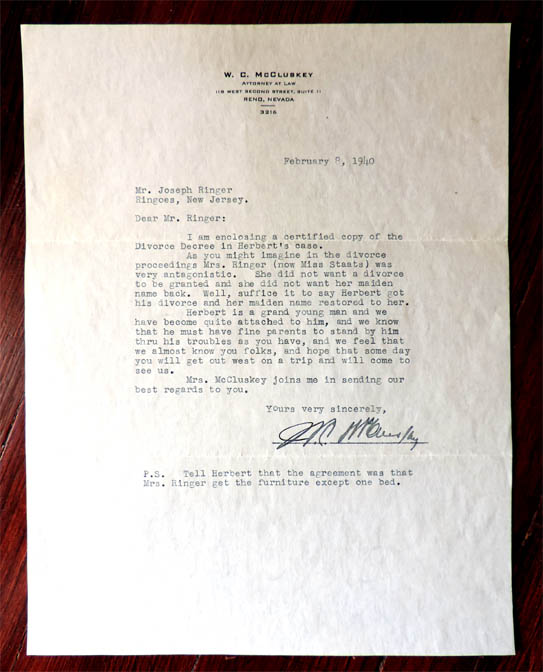

“Oh, Jim…I know how you feel. I was married once. 1939. It didn’t work out. Finally I drove from my home in New Jersey to Reno and finally secured a divorce. He paused for a moment and then continued…

“It wasn’t that I didn’t love her. I loved her so much. I still love her to this very day.”

It had been a rough, almost unbearable year for me. (And of course now, all these decades later, I’m dealing with another divorce…one that I never saw coming.) My first failed marriage, though crushing, had also seemed inevitable for more than a year.

But then, on that hot late summer day, I saw the emotion and the sorrow that could still reduce this new friend to tears and I thought to myself, ‘I hope I don’t feel; this way in 40 years.’ The irony is, I do. But under different circumstances.

In any case, from that moment on, Herb and I were more than friends. We were kindred spirits. Two men who had shared a similar heartbreak. Herb Ringer was one of the most empathetic men I have ever known. In the years and decades to come, I would see the emotion sweep over him time and again, as he sensed the pain and suffering of others. I never knew if Bill Clinton really “felt our pain.” But I know Herb Ringer did.

Over the next few years, Herb’s semi-annual visits became an “event” that I looked forward to, and we kept in touch by letter, back in the blessed days before the internet. I came to understand his annual routine — he lived in Fallon, in the same 42 foot Smoker trailer that he and his parents had occupied since 1954. His father died in 1963 and his mother a decade later.( I’ll explain that part of his past in a moment.) But after his mother died, Herb was on his own and he developed an annual schedule that he stayed with until his eyesight forced him to quit.

Every February, Herb would start packing up the van. By the middle of the month, he’d leave the trailer and head south, in search of warmer temperatures. Then as spring pushed the last remnants of winter away, he’d work his way slowly north. Depending on the weather, I knew I could usually expect him by May. The campground could still be busy in the Spring, but I was the ranger at the Devils Garden and self-proclaimed Lord of my Domain. I always made sure there was an open campsite for him, and when I learned he was barely surviving on his social security check, I waived his fee as well. Even that small gesture could make Herb tear up. But with every visit, I learned more about his life. And as I told my fellow rangers about Herb, he became a part of our “inner circle” of regular park visitors, for whom we cherished as the kind of tourist we wish they all could be. The other rangers came to love Herb too, and my fee collecting partner had no problem ignoring that $1.50 fee each night.

From Arches, Herb would head east. Some years he made the long transcontinental drive to the east coast to visit friends and family. He still had relatives in New Jersey and he often spoke fondly of the Horn Family in Connecticut. Or the Leonards in Minnesota. But I knew few of the details; I only knew that he had what one could almost call a network of friends, from Nevada to New England, and it must have been those countless “Herb Fans,” like us in Utah, that sustained him.

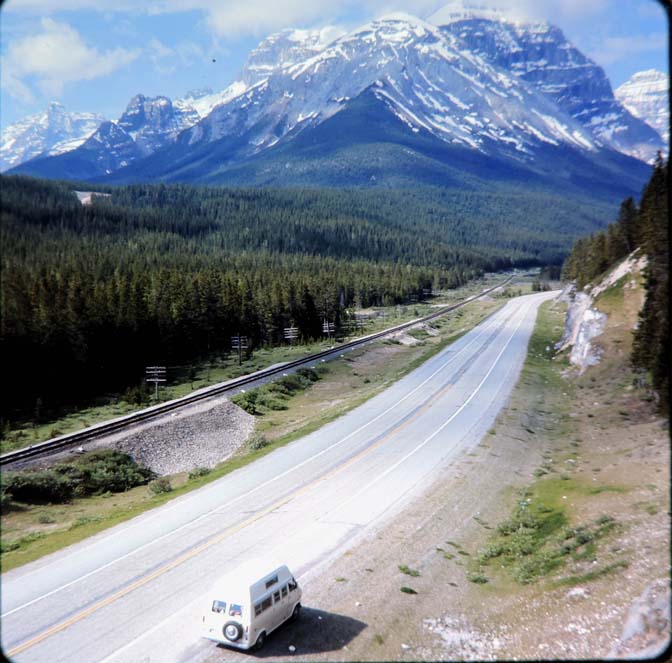

Eventually, each summer, he wound up in Colorado. This was his true love, as evidenced in part by the thousands of color images he shot over the years. But it went deeper than that. Herb was as brilliant a Colorado historian as any college professor who earned his Ph D in the subject. During the cold winter months when Herb was back home in Nevada, he’d occupy his time writing histories, from memory, of the mining towns and railroads of the Colorado Rocky Mountains.

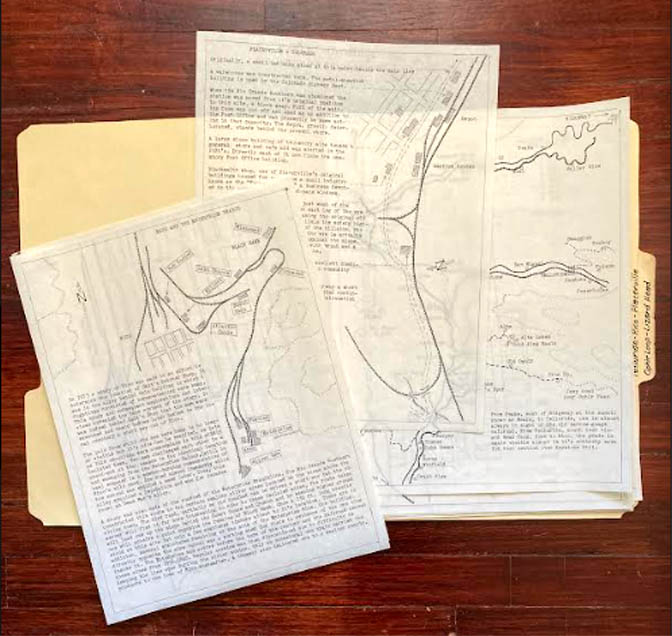

He was also a self-taught and naturally gifted cartographer. He was an artist in so many mediums. Herb took it upon himself to create hundreds of detailed, to scale, maps of the ghost towns of Colorado as he discovered and explored them. I have never published any of these works of art and someday, I need to find the proper keepers of these masterpieces to preserve after I’m gone. But it’s time to share a few, if only to pique the interest of Coloradans who would hopefully appreciate their value.

*****

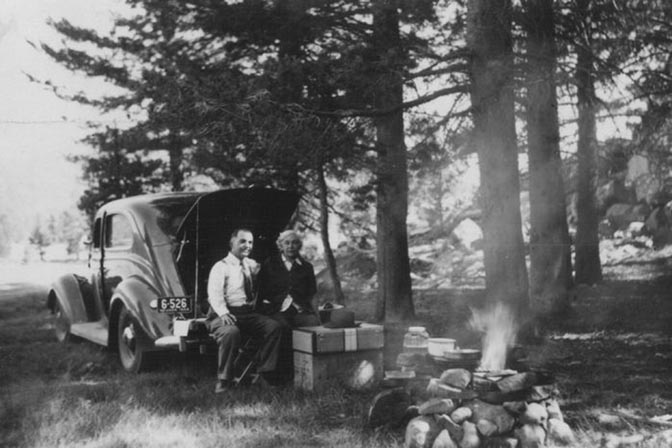

Until Herb told me that all his knowledge of western history was due to his own personal interest — passion might be a better word — I assumed he had been a history teacher or college professor. Herb laughed and told me he had never even officially finished high school. When he was just eight or nine, he came down with rheumatic fever and almost died. He missed a year of school, and from then on, he was homeschooled by his mother and father. He admitted to being a bit smothered by his mother, Sadie, who was terrified of losing their only son. His schooling was more complicated by the fact that his father, Joseph Ringer, was a professional musician and played in orchestras from New York to Cincinnati, and other locations in the East. Once, when Herb was just four, his father was hired to be part of a summer bandstand orchestra in Colorado Springs. They traveled by train and Herb got his first taste of the West.

(Much of that early history, and especially a wonderful gallery of photos taken by Joseph can be found in a Zephyr post from October 2022. Click here to access that post.)

By the mid-1980s, Herb was a familiar face and when he passed through the Arches entrance station, I’d often get a call on the two-way radio that my “buddy Herb is on his way up.” Finally, a friend and I decided it was time to visit Herb. Our trip was planned for mid January, but her sudden death and the grief that all the park staff felt put an end to the journey. Because Herb was only in Fallon for three or four months a year, he didn’t have a phone. I had to write him a letter to break the news to him. He responded immediately, again overwhelmed by the loss that he shared as well. It was one of the hardest times of my life.

But in early February, though it was still cold in southeast Utah, I heard a knock on my door one morning, to find Herb standing there. I couldn’t believe it. He hugged me, the tears flowed from both of us, and I invited him in. There was so much to say and yet words failed both of us. He stayed for almost a week and most days, we just drove around…sometimes we talked and often we just rode in silence. But it was his mere presence that mattered. I had already known what a gentle and caring soul he was. Now thanks to Herb and another dear friend from my parents’ generation, Reuben Scolnik, I was able to lean on them during this hard time. Both men, over the years, became the father I never really had.

During Herb’s February stay, I had urged him to stay at my place in town — In April 1985 I had bought a little bungalow on Locust Lane for $18,000. But Herb refused; as always, he had his cat Namtu with him, and I still had my dog Squawker (Muckluk had died the previous October). But I convinced him to pull his van into my driveway and I ran an extension cord and small electric heater to the camper.

Finally, after almost a week, he felt he needed to go. His plan was to drive south, where the weather was warmer, then east along the southern tier of the country. He figured by the time he reached the east coast, spring would have arrived. As we prepared to say our goodbyes, he walked out to his van and came back with a small paper sack. He said, “I know you love history like I do. And I know this is such a bad time, but maybe someday, you’ll enjoy them.”

I was so distracted by everything else happening in my life that I simply thanked him, numbly took the bag without even looking inside, and after he had driven away, I stuffed it in a dresser drawer. I completely forgot the sack was there.

We continued to correspond by mail and Herb would give me general delivery addresses in small towns across the country where I could write back. Herb knew the routes back east so well, and especially Colorado, that he once gave me a typed list of places along his various routes, literally all the way across the country, where he could camp for free. They were listed in geographical order — he’d note that he could camp in a church parking lot in one small town, then a Wal-Mart lot a couple hundred miles east, then a friend he knew a bit farther. And in each of those camp spots, the people all remembered him and knew him by name. Just like Arches. If you ever wanted to know the man who “made friends wherever he went,” it was Herb.

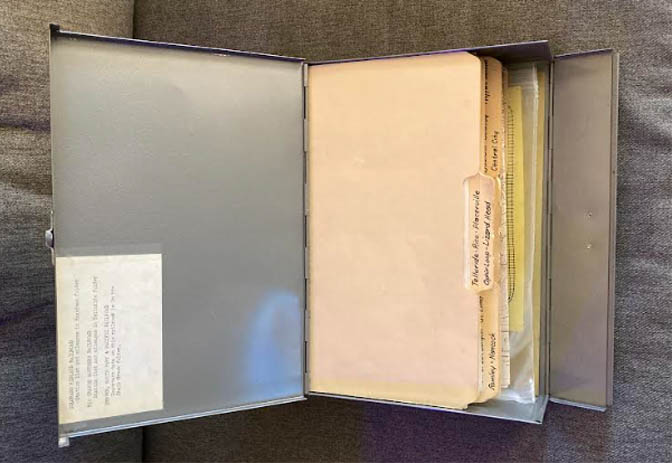

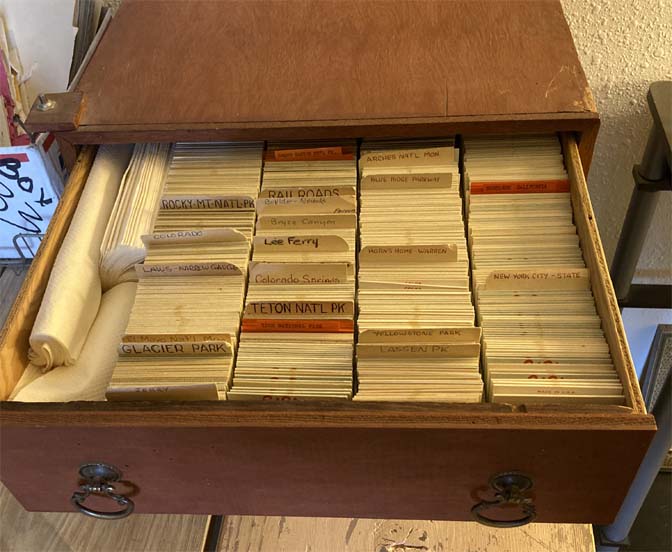

Many months later, in the autumn of that year, I was sitting in my living room, bored to death and watching tv, when the memory of that paper sack made its way to the front of my brain. I had to think for a moment to remember where I’d put it. I found the bag and peered inside. In neat bundles, wrapped in rubber bands, and labeled by location, were several hundred Kodachrome color slides. I pulled out my father’s old Tower slide viewer and started looking at each collection. Herb had never even told me he shot photographs like this, or that he’d used Kodachrome film. Or that he’d been taking Kodachromes almost from the day the film became available to the public, back in the 1940s. Now in his 70s, Herb had finally given up his more expensive cameras that I didn’t even know he owned, and had resorted to a simpler point-and-shoot. Now, for the first time, I saw these amazing images. I expected to see him soon and sure enough, he arrived in October. He was delighted that I was so pleased with this unexpected gift. He said, “Oh Jim…I have thousands of these. And journals. Old pamphlets from across America. You would love them.”

He arrived just a couple weeks after my last day at Arches. My last day ever. After eleven years and all that had gone down in the last year, it was time for me to move on. Just what I would move on to was a mystery. And pretty scary as well. Although my little house was incredibly inexpensive, I still had to borrow $16,000 to pay off the balance. I had to tell Herb I could no longer waive his camping fee and he shrugged. “It was only a dollar and a half,” he said. “No big deal.” But it was bigger than he wanted to admit, and in the next few years, I’d learn how poor he was. And I’d learn why. But he still felt uncomfortable camping in my driveway and since the October weather was beautiful, he liked to camp at the old Lions Park, before it became whatever it is that New Moab did to it, and the money it spent, to make it ‘better.’

In the late 1980s and early ‘90s, the Lions Park, adjacent to the Colorado River, and at the turn onto Highway 128, was just a big parking area, with a few picnic tables, some fire grills, and surrounded by big cottonwoods. For free it also often provided a nice breeze. He didn’t seem to be bothered by the mosquitoes (which were also free). So when Herb was in Moab, I’d often drive out to Lions Park in the evening and find him —only Herb — in an otherwise empty lot.

He liked to set up his lawn chair by the side door, facing the river, and more times than not, he’d be reading his Bible. He was my kind of Christian. I don’t think he ever once asked me about my own religious views; he was simply content with his own. He was the kind of Christian who practiced his faith quietly and who demonstrated his beliefs via his deeds and his kind heart. He wasn’t much of a proselytizer.

*****

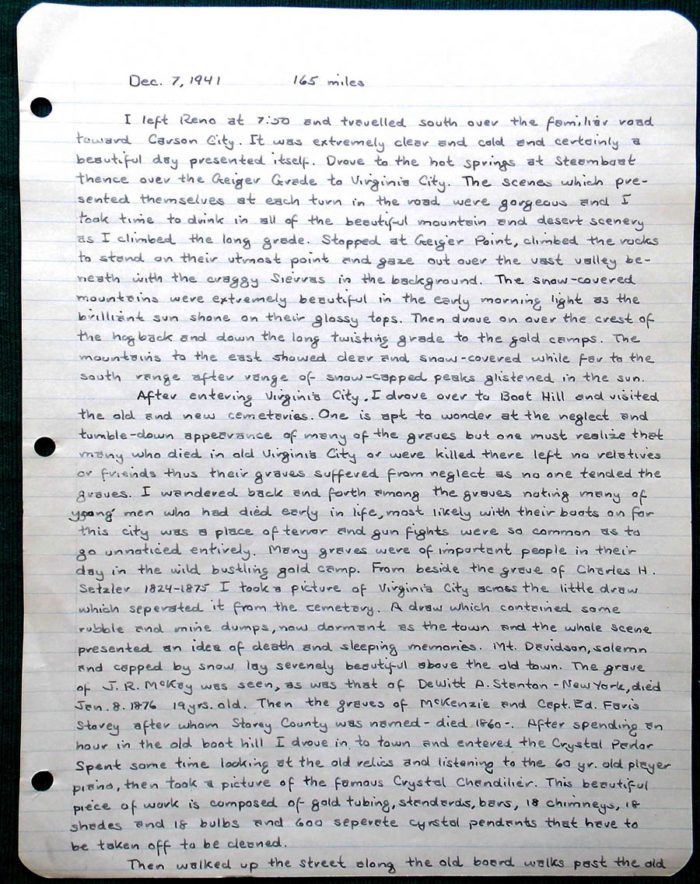

The ritual continued, and in 1989 I started The Zephyr. From that first issue, I made good use of Herb’s gift of old photos, but I was on a budget of my own and could not afford to post his magnificent Kodachromes in color. It would be more than a decade, with the advent of the internet and The Zephyr website, that anyone had ever seen his pictures as they were meant to be seen. Still, he was thrilled to see his pictures and some of his journal entries, going back to the late 1930s. He had even recorded, in his impeccable penmanship, the day he went exploring a ghost town and came home that evening to see the newspapers. It was December 7, 1941. Pearl Harbor.

In the early 1990s, however, I received a disturbing letter. He had been diagnosed with colon cancer and was to undergo surgery. He had friends to help him, but I couldn’t get away to be there with him and worried that I might not see my friend again. But a few weeks later, I was in my home office, working on the next Zephyr when I glanced out the window and saw a familiar sight. It was the Ford Econoline camper van. What the hell? I thought. I ran out the door and sure enough, there was my buddy.

“HERB!” I yelled. “How in the world are you out on the road? You last wrote you were facing colon cancer surgery.”

In typical Herb Ringer understated fashion, he shrugged. “Well. They were able to cut the bad part out and hook my plumbing back up. I sat around the trailer for a month and decided I was wasting my time. I felt okay. I needed to get going again.”

I asked him what the doctors had said. Herb smiled, “Well, they weren’t all that pleased, but they knew there was no point arguing with me.” He may have only been five feet tall, but Herb Ringer could be a force to contend with.

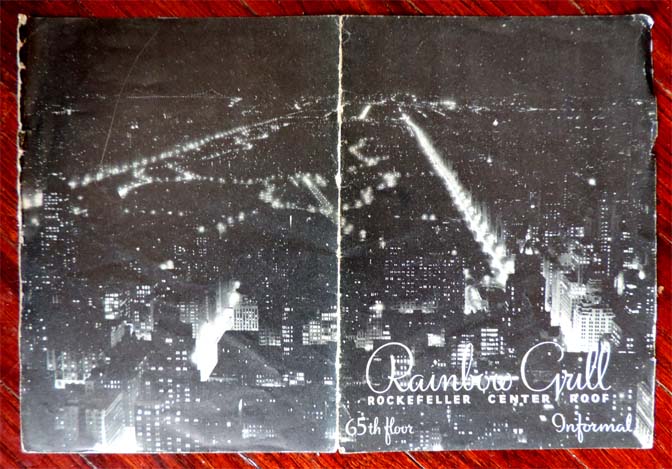

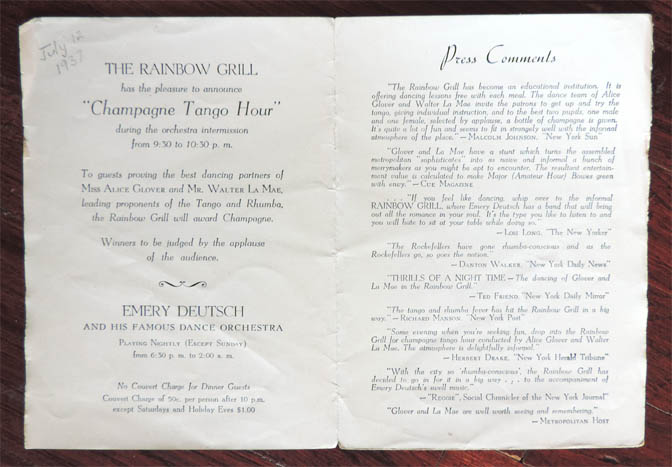

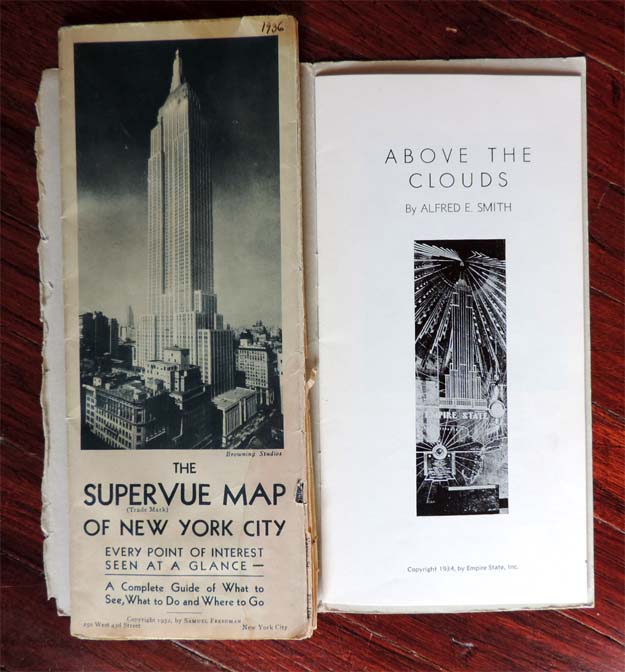

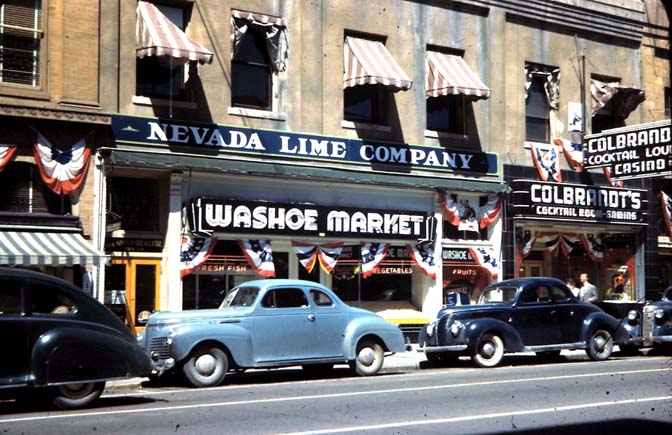

Still, that winter, when I knew Herb was back in Fallon, I made the long drive across US 50 to see him. It would be the first of many trips. He was gracious as always. It was the first time I had been to his home, the same 42 foot Smoker trailer that he and his parents had bought in 1954. The purchase had even made the news in Reno. At the time, the paper reported, it was the largest travel trailer ever brought to Reno. Despite its size, the Smoker was extremely well built. The cabinets were real wood. So were the floors, though much of it was covered with carpeting. It was a cozy little home, perfect for one person. But it’s what he kept within those walls that was remarkable. The trailer was full of memories. Loaded with history. He showed me the oak bookcase he had built himself; it was full of books on railroads of the West. And mining towns. He pulled out box after box, brimming with national park and national monument pamphlets that dated back to the 1930s. He had a 1937 pamphlet promoting the Rainbow Room at Rockefeller Center in New York. He showed me another booklet, a lofty introduction to the Empire State Building by then Governor Al Smith. On a wall mounted display case, he showed off some of his mining ghost town relics. All of them treasures, to Herb at least. His entire life was within these walls.

Another proud possession was his model railroad collection. He told me that years ago, when both his parents were alive, he had built narrow continuous shelves around the entire inside perimeter of the trailer and on it, he’d laid HO Gauge track for his model railroad. He had also constructed from balsa wood — some from kits, others of his own invention — buildings and homes and shops to complement the train. Since then, he had taken down the track and given away most of his model buildings, but he held tight to his favorite HO engines and cars. Herb kept them in the original boxes, but he put one of his favorite cabooses on the wall display case.

On my first night there, I offered to do the dishes but I kept waiting for the hot water to come on. Finally I asked him if it was lit and he told me that his hot water heater had quit working more than five years ago and he didn’t have the money to replace it. I could understand why he spent so little time there. The trailer gas heater worked at least, so he wasn’t living in an ice cold home, but he didn’t even have the basic pleasure of a warm bath. When I got back to Moab, I talked to a few friends who knew Herb and together, we raised the money to buy him that water heater and have it installed. Herb was happy but also chided me for it. He explained that most of the year, when he was living out of his van, he was accustomed to sponge baths and that being at home without a warm tub was no different. I told him if he wanted to keep taking sponge baths in Fallon, nobody would stop him, but at least the sponge would be warm.

*****

The following summer, everything changed. Herb was in Colorado visiting friends in Salida and Crested Butte. I drove over to meet him and spend a few days at his camp at Lake Irwin on the Kebler Pass Road. He was there, but was distraught. He had been having vision issues and his friend Lynn in Crested Butte had encouraged him to see a doctor. She scheduled an appointment for him in Gunnison with an ophthalmologist and on August 12th, he received the bad news. It was macular degeneration and already advancing at an alarming rate. He wrote in his journal, “I must return to Fallon” It was one of his last journal entries. He stopped in Moab on his way home, a week later, and I asked if he’d be able to make the trip. He was struggling but felt sure he could see well enough to drive home. It was US 50 after all, he reminded me. “The Loneliest Road,” so he felt if he did crash his van, it was at least unlikely that he’d hit anyone.

And it was then that my regular trips to Fallon began. On my first longer visit, I began to realize just how financially strapped he was. He didn’t have any life savings; he explained to me that when his father was diagnosed with cancer, he had spent all of it, more than $40,000, on hospital and doctor bills. This was 1963, the year before Medicare was enacted. There was no “safety net” at all and Herb never recovered financially from it.

For people who complain about the welfare state and the way it is often abused, the complaints are often valid. But there is another side to the story and Herb was the perfect example. He had worked long hours as a grocery store manager since he was in his twenties. He later told me he learned “the grocery business” when he still lived in New Jersey. When he moved to Reno, he worked at several stores over the next three decades. But now, at 80, he was trying to live on a $500 a month social security check. It seemed like there had to be services and assistance available that he had not tapped into, and I was right. He had never been to the social services office. So on that first long stay, I arranged for a meeting at the local office in Fallon.

The people who worked there could not have been kinder, and like everyone else, fell in love with Herb from the moment they met him. I explained the situation and the social worker in charge replied that they were unaware of his difficulties. Like so many others like him, especially of that generation, persons seeking assistance needed to ask for it. They didn’t know Herb existed. But now, they went out of their way to improve his financial and living conditions. She later told me that while many people seeking help often infuriated her, Herb was the kind of client that they’d go to the Moon for.

As it turned out, there was a plethora of services that were available, that Herb had never thought to ask for, simply because he had never thought to rely on anyone but himself. Even now he hesitated, but the staff explained to him that he had earned this assistance. He had worked his entire life, had paid his taxes, had cared for his parents to the day they died, and when I reminded Herb that he had spent his life savings on his father’s cancer treatment, a year before Medicare, Herb shrugged. “Wouldn’t anyone do the same thing?”

The social worker and I looked at each other. She immediately set in motion a series of actions that would make his life, financially at least, easier. Because of his macular degeneration, he was declared legally blind, which allowed a significant increase in his monthly social security payment. He was eligible for food stamps. Another program provided assistance for the cost of heating his trailer. Herb declared, “I feel like a rich man!”

Herb was ecstatic and that night, he insisted on taking me to dinner at the Stockman’s Casino, just a couple blocks from his trailer court. He insisted we both order steaks and when dinner came, he cut into his meal and said, “This is the first steak I’ve had in ten years.” It almost broke my heart.

The next day was special for both of us, but especially for Herb. In so many previous stories and posts, I’ve described his many trips to Hope Valley in the High Sierras. He and his parents had first ventured there in June 1945, and had spent a very cold night, sleeping in their 1941 Lincoln Zephyr. It was just a couple hours from Reno, and over the next 18 years, Herb and Sadie and Joseph made that drive again and again. But he had never returned after his father’s death in 1963. Now, in 1995, we were returning. His eyesight was poor and the views were fuzzy, but he could also feel his way there. When we reached the valley, Herb instructed me to pull over by a certain meadow. “This is it,” he said. We got out of the car and Herb soaked up the sun and the memories of all those days and nights that he had spent here, with his parents of course, but also friends that had accompanied them over the years.

Herb could tell me exactly how many Hope Valley trips he’d made. “We had come up here 259 times when my father became too ill to travel….now this is trip number 260.”

*****

During these longer visits, we talked more about his life and he confided in me some of the more personal details of it. His mother Sadie lived another decade after Joseph died. She and Herb continued to travel, often heading north into Canada, to Banff/Jasper National Parks. Herb told me of another family that they had come to know over the years, who also traveled to the Canadian Rockies. He never gave me any details, but once I asked him if he had ever considered remarrying. He told me of his friends. Like Herb, he mentioned the daughter of the elderly couple they had come to know. She was very much like Herb, committed to caring for her parents as long as they lived. “We lived in different parts of the country, and there was no way we could have resolved those difficulties. So we gave up on the idea.”

In 1973, while in Canada, Herb suffered a severe heart attack. An ambulance was called and as medics placed him on a gurney, Sadie suffered a massive stroke. She died, almost instantly. Herb was unconscious and only learned of her death the next day. He never wanted to talk about the details that followed her passing. He only told me that eventually, he returned to Reno and Sadie was buried beside Joseph at a local cemetery. Herb decided it was time to retire and relocate his Smoker trailer to Fallon. He made one last visit to his parents’ graves. He knew he had to let go of the past after a lifetime living with his mother and father. “I said ‘goodbye’ to both of them, and I never returned to the cemetery.

During these long conversations, thoughts and memories would come to him and he would share them with me. Some were heartfelt and sometimes funny. One day, out of the blue, he said, “My mother could never pronounce my name.”

“What?” I asked. “What do you mean?”

Herb laughed. “Hoi-but.”

“Hoi-but?”

“Yes. For some reason she could not say ‘Her-bert.’ She always called me ‘Hoi-but.’ It was the only word she could never seem to pronounce correctly. I never could understand that.”

Once, really sticking my neck out, I asked him, since he lived in Nevada, where prostitution was legal, had he ever…you know…I asked. “Did you ever acquire their services?”

Herb laughed. “Oh my Heavens NO! I could never do that. I knew many of the ‘girls’ and some were good friends of mine, but that would not be right.” He went to his photo box and found the photographs of the two ‘girls’ he once met at Rhyolite, Nevada. Later he told me the story and gave me the pictures to copy. It was just one of the many stories that I’ve been able to share in The Zephyr. Here’s the link to his Rhyolite story.

My visits were never long enough for either of us, but I always had to come back to Utah and The Zephyr and my life there. As always, we corresponded by mail. Even now, his hearing was too weak to use a telephone. But he adapted remarkably well, in part because in addition to the other assistance he had recently received, there was a service that provided a housekeeper to visit him twice a week. She helped tidy his trailer, and to cook him a hot meal. But more than anything, it was her company that meant the world to him. And for the life of me, I cannot remember her name. But it might have been Becky, so I’ll leave it at that.

She and Herb became good friends and until 1997, he was relatively happy; he adapted to his more restrictive lifestyle. Herb took walks downtown and had been provided one of those white walking canes to indicate he had severe vision issues. Though his sight was impaired, he did well enough to make his way to Auction Road and US 50. He counted his steps and could tell me precisely how many of them it took to reach the local grocery or pharmacy.

But in the spring of 1997, Herb received some hard news. ‘Becky’s’ husband was about to take a new job, in a different town, and she would have to quit her job. Herb was stunned and she felt awful, but there was nothing she could do. Social services started sending another person to replace Becky, but it wasn’t the same. She had felt like a friend. To Herb, her replacement seemed impersonal and distant, treating her visits more like a job. To be fair, the woman was probably doing her best, but sometimes the chemistry is just not there. Herb in effect fired her. From then on, his health began to decline.

Early in the summer, I made the trip to Fallon once more and found him to be in poor spirits. He invited me in, as always, and gave me a hug. But there was a spark missing. When he sat down and I asked him about his health, he pointed to his ankles. They were swollen to twice their size and I knew enough from my ranger days that swollen ankles and legs were a sign of congestive heart failure. Pulmonary edema. Had he seen a doctor, I asked. Herb nodded but told me the physician at the hospital had noted the swelling, but said nothing and sent him home.

I can get a bit demonstrative at times, and this was one of them. I drove him back to the hospital, to the Emergency Room, and showed the nurses and ER doctor on duty his legs. Whatever was wrong with the previous physician, these people took his condition seriously and admitted him immediately. Like almost everyone else who ever met him, the staff and especially the young nurses, were charmed by Herb, and he received the kind of attention he had missed. He was grateful for the medical assistance, but more uplifting to him was the company. He loved the conversations and I could see his spirits rise. He was seeming like his old self again.

That afternoon, however, when I checked in on him, Herb was staring blankly at the wall and I worried that he was slipping again. He hardly noticed I was there. Finally I said, “Herb…what are you thinking about?”

Herb said, “Ariel Sharon.”

“Say what? ‘Ariel Sharon?’” He asked me if I knew who he was. Of course I said. He had been Israel’s defense minister and a controversial political leader. But why was Herb thinking about Ariel Sharon?

“Well, I was watching the news and saw him on tv. I remembered that in 1973, Sharon visited President Nixon at the White House. Everyone was wearing suits and ties, but Sharon showed up with no tie at all. At the White House! I always thought that was quite disrespectful.”

I said, “Herb…That’s what you’re thinking about? Ariel Sharon’s open collar?”

“Yes,” he replied. “If I was invited to the White House, I’d most certainly wear a tie.”

A few days later, Herb was discharged and I took him back to his trailer on Regan Place. I could see his spirits already slipping. He missed the human contact and conversation. The sense that people cared about him. Now, without Becky as well, the loneliness hit him hard. We talked about hauling his Smoker trailer to Moab but he rejected the idea. Nevada was where he had lived since 1939. It was where it would end.

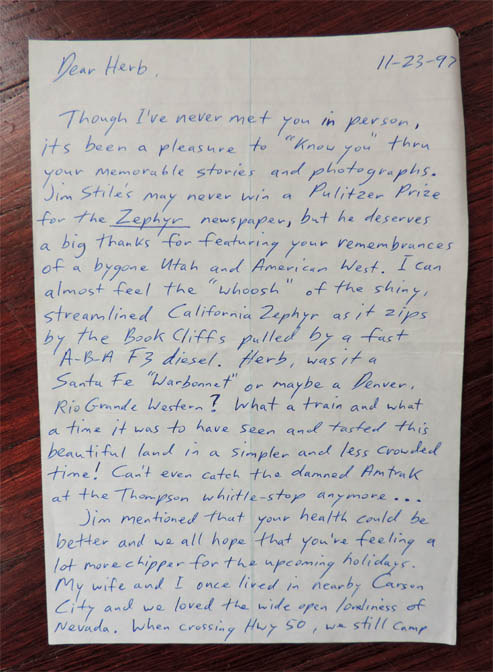

In November, I mentioned to Zephyr readers that Herb was facing some serious health issues and that he was alone in Fallon. And so I asked them in my Page Two editorial to take the time, if they could, to send him a Christmas card. He’d love to know his work was appreciated.

I hesitated to provide his physical address, so I asked readers to send their cards and notes to me, and I would bundle them up and send all of them directly. The response was overwhelming.

More than fifty cards and letters filled The Zephyr post office box, and I started sending him batch after batch. The notes that accompanied the cards were some of the most heartfelt, loving notes I’d ever read. Herb had no idea that his photographs and stories had reached so many people, and that they had been so moved by his talents, and by the life he had chosen to live. Herb was delighted and he filled his trailer with the cards and read them again and again.

I made one more trip, for just a few days, but I soon had to get back to Moab and it was hard to say goodbye. To make matters worse, for Herb especially, I had made plans to visit Australia in January. I’d be gone for a few months. But I had learned I could make long distance calls to the US for a reasonable price —he had finally relented and had a phone installed at his trailer. Again, social services came to his aid and provided a booster speaker for hearing impaired users. I was able to call him regularly and we had some good chats. The phone seemed to help.

But months later, when I was back in Moab and working on the next issue, I tried to call him, but got no answer. At first I wasn’t concerned; most likely he just couldn’t hear it ring. But after several days, I looked up the number for the social worker I had come to know. She said she would make some calls and find out. An hour later, she called me back. Herb had started taking himself back to the hospital. Day after day. He insisted he was ill, but the doctors would send him home. I was never able to determine what had actually happened — none of the hospital staff would talk to me — but finally they admitted him and sent Herb to the state mental hospital! The social worker had no idea and she was able to have him released immediately. She obtained the phone number and I was able to call him directly. He was so upset. He just kept pleading, “You must get me out of here!” I left for Fallon the next week.

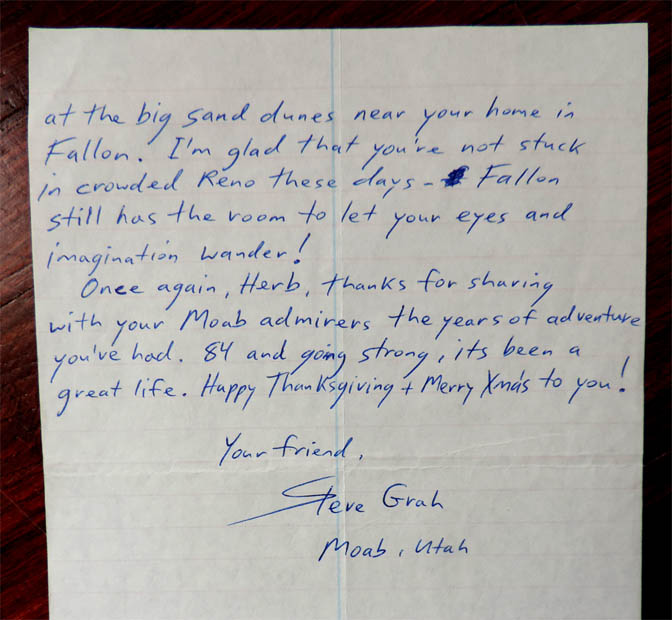

Herb was home by the time I arrived, but I was shocked at how badly he had declined in just a few months. Now, almost everyone Herb knew was trying to convince him to move into a nursing home. It was nearby and it was a nice, sunny facility. Herb could no longer care for himself as well as he needed to, and he had rejected the housekeeping service.

I didn’t know what to tell him. I could see how he had changed in such a short period of time, but on the other hand, I couldn’t imagine him giving up his independence. He was also a very private man and he would be required to share a room. We drove to a nearby park and sat together at a picnic table. I knew it had to be his choice and we weighed his options. None of them seemed appealing. In the end, he felt he had no choice but to accept the inevitable and make the move.

I had to go back to Moab yet again, but in late July, I returned and drove my pickup truck to help with the move. He started pulling out box after box of photographs. His journals. His fathers journal. He gave me boxes of artifacts from his ghost town days. He even wanted me to take his cameras. He found items in drawers and crates that he had not looked at in years, but Herb wanted me to have them. He even insisted that I take the oak bookcase that he had built for his parents many years ago.

There was also the Smoker trailer to consider — his home since 1954. The young man who lived in a tiny trailer next door saw our activity and stopped by to say hello. He offered to buy the Smoker for $1500. Herb accepted. He found a buyer for his Ford van. He had put almost 200,000 miles on the Econoline since he bought it, brand new, in 1971. Now he sold it for $700. Still, there was so much left. Clothes. Kitchen pots and pans. We took several loads to the local Goodwill store, but ultimately, some of his personal belongings went to the landfill. On his last day, Herb sat alone at his kitchen table, while I moved the items he intended to take with him to the nursing home.

Finally, he said goodbye to the Smoker and the trailer court and we made the short drive to his new home. I felt sick and could not imagine him there. But from the first day, I at least knew he would have an advocate. Her name was Pat Lee and she was a nurse at the nursing home. Like so many others who had met Herb, she immediately took a personal interest in him and truly became his last real friend. Knowing Pat was there helped, but as Herb and I said our goodbyes and he hugged me, I knew this was a final farewell. Pat walked me to my car, and I gave her my phone number. She promised to keep in touch. But within weeks, Herb’s physical and mental health deteriorated. Pat had been able to hook up a phone with the speaker booster and one day, I got a call from the nursing home. I can’t remember if it was Pat or another member of the staff. But the call was placed to me on Herb’s behalf. She said Herb was having a good day and thought it might be helpful to talk to me.

He came on the line and Herb sounded cheerful but strangely detached. I asked how he was doing and he said he was well. I pressed him for more details, but he said everything was fine. I mentioned my last visit and he failed to reply. I asked him about some of his photographs; earlier that year, with his eyesight almost gone, I had been able to sit at a table and simply describe the image, and Herb would be able to tell me precisely the location, who was in the picture and what year and month he took the photograph. Now all he could say was, “I’m not sure.”

Then it struck me. “Herb…you know who this is, don’t you?”

“Of course,” he replied. “…of course I do.”

I said, “Who am I Herb?”

There was a long pause. He said, “I’ll get back to you on that.”

He no longer knew who I was.

Weeks later, I received a call from the hospital physician. He informed me that Herb’s cancer had returned and that he had stopped eating. Since I had Power of Attorney, he wanted to confirm that Herb was okay with the DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) form he had signed, if it came to that. Herb and I had talked at length, a year earlier when he was in the hospital that first time, and more than anything, he didn’t want to keep living if he could no longer be Herb Ringer. I told Herb that I felt the same about my own life.

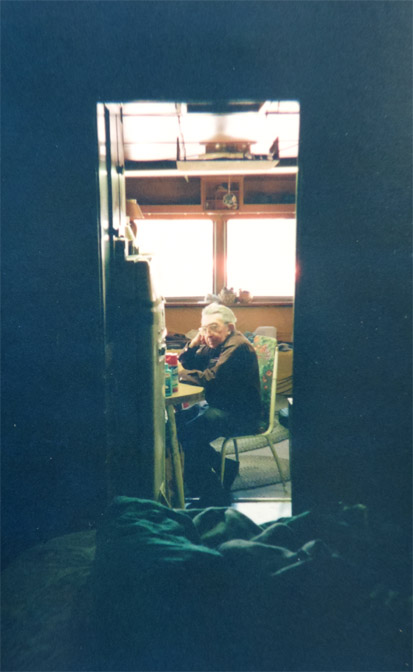

In 1998, December 11th fell on a Tuesday. That was “Zephyr Press Day” for me. With Herb on my mind, I featured him on the cover, with a photograph of him as a four year old boy, and another from the past summer. The Zephyr was printed in Cortez, Colorado at the time. The December/January issue was loaded into the back of my pickup and I made the two hour drive back to Moab. An hour after I arrived, the phone rang. It was Pat. Herb had just died.

*****

Pat took charge on my behalf. Herb had wanted to be cremated and Pat insisted there was no reason for me to come back yet again. I admit I was exhausted and grateful for her help. Hardly any of his personal possessions remained there. She placed what was left in the green footlocker and with his ashes, shipped it to me later that winter. Over the next decade, I scattered his ashes at locations across the West that had provided him with his fondest memories. But I have never been able to part with all of them. A bit of Herb still resides in his oak bookcase.

I will always be grateful that Herb entrusted me with his photographs and journals and other artifacts of his life. I’ve tried to do my best to keep his memory alive. But all I’ve really done is be a conduit for the brilliant memories he recorded on film, and via his handwritten stories. I wish he could see how many Zephyr readers have been awed and amazed at the work he did, though Herb would have never called it ‘work.’ It was his passion and love of the land, and his family and friends that motivated him. Until I came along, he never thought his efforts would be of any value to anyone. But I still remember one of those last visits, when his eyesight was about gone and I was describing some unlabeled images. His memory was incredible. I said to him, “How do you do that, Herb? You haven’t seen these pictures in years.”

He pointed a finger to his head and smiled. He said, “I can still see everything.”

*****

SOME ADDITIONAL HERB RINGER & FAMILY PORTAITS

NOTE: There are so many stories and photographs that I’ve posted over the years. Some of this might have sounded familiar from past posts, but there’s still so much I to show Zephyr Readers. I could spend the rest of my life sharing Herb’s treasury of pictures & words from a time long past. Again, to access most of the online Herb Ringer stories and images, click here.

Jim Stiles is the publisher and editor of The Zephyr. Still “hopelessly clinging to the past since 1989.” Though he spent 40 years living in the canyon country of southeast Utah, Stiles now resides with two cats, Rambo & Rascal, on the Great Plains. Coldwater, Kansas is a tiny farm and ranch community, where there are no tourists.

He can be reached via facebook. Messenger, or by email: cczephyr@gmail.com

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE VERY BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE.

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

REMEMBER! I’D LIKE TO HEAR FROM ZEPHYR READERS. TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE VERY BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE.

How blessed you both were to have been in each others’ lives. My deep sympathy to you Jim for the loss of such a friend. Chemistry is a rare thing in life.

Thanks. We were both lucky. There is so much more to share and hardly enough time to complete the project. So many more photos. But there are boxes of typed, single space histories that he must have written to occupy his winters. I didn’t know about these until it was too late to ask him about them.

Beautiful. Thank you for sharing

I almost felt as if I knew Herb! His loss was/is very hard but you should take satisfaction, knowing he knew what a true friend you were and that his treasures would be in good hands. How fortunate to have had such a wonderful friendship. Many people never know the true meaning of friendship during their whole lives! The pictures of the two of you are prime examples of that long term friendship. Thank you for a wholesome, brought-to-life episode in both your life and his.

Thanks Donna. To think you and Gail were living just a few hundred miles south of the Ringers and had already been there for years when Herb arrived in Reno is amazing. Thanks for all your input.

So many thoughts. Herb was an artist and his photos became a thread in your paper. The west, light, shadow and content. Herb is a story of art, personal evolution and friendship. You have done a fine job of keeping Herb’s legacy alive Jim and we have all benefitted.

Thanks Dave. I’ve been wanting to rewrite an old story I wrote about our Glenmeade Road days. I’ve been finding more old photos of our backyard that shows the Woods and Miss Huntsingers field before more developments appeared all around us.

Oh my gosh that is a beautiful story,,so much I had forgotten..Will you put that in book form one of these days? You should. You are a great writer and so much history in your life..You should share..Wish I were younger and healthy….Blessings to you always…

Jim, thank you for such an endearing chronicle of a wonderful man and your deep friendship. I must admit your article is a real tearjerker in places, and brings to light the value of friendship and good friends. Happy holidays!

Indeed, there are a lot of us out there who have benefited by your channeling of Herb’s photographs and stories. It makes the story of his final days all the more touching, especially knowing how you were there for him. A friend of mine relates the aphorism: “There are three kinds of friends in this world: friends for a reason, friends for a season and friends for life.” Herb was one of the lifelong kind and you were fortunate to count him as yours.

The three kinds of friends. Perfect. Thanks Evan.

Another beautifully-written essay. Your friendship with Herb was so deep and profound! When I was a boy, I never saw adult men weep like you describe Herb weeping upon hearing of your first divorce. He is the type of man whose friendship I would cherish, I know! (As for where Herb’s scale drawings of mining towns in Colorado can go, perhaps the Colorado Mining Museum in Golden may want them to put on display.)

The Colorado Mining Museum is a great idea. I’ve also been taking to a writer in Colorado about preserving his life “work,” which never felt like work at all.

This is a genuine love story and I greatly appreciate the beauty that you shared with me as a reader. You and Herb are authentic people. I also include nurse Pat in that recognition: however brief her role was it was heroic, in my view, and the epitome of compassion in duty. I’m very moved by your account, sir, and thank you for sharing Herb with us in such a reverent way.

Thank you so much for sharing this Jim. You were a great friend to a special man for sure. I hope that you can find a home for some of his work. I’m sure that he knew how much you loved him at the end.

Thanks. As far as Herb’s archives, I know there are several options, but I don’t want them to disappear in a climate controlled storage building, with a complicated process to access them.