FOR THE GLEN MEADE ROAD KIDS…

NOTE: I’m not sure if this story would be of much interest to anyone but me and a few friends, if it weren’t for the photographs that accompany the story. I owe it all to my late father, who was a gifted photographer and a dedicated family documentarian. When I was born, my father, Jim Sr., was manager of the camera department at Sears Roebuck, in Louisville, Kentucky. He was able to get a discount on a good 35mm single lens reflex camera, as well as a break on Kodachrome Color Film. He shot hundreds of photos in those early years and he carefully catalogued them and stored them in the old metal Tower slide trays (before the Carousel projectors). I became aware of his collection many, many years ago and even at 20, realized their value, at least to me. I’m glad that I ended up with these images. I’m the last man standing in my branch of the Stiles Family. And I don’t know how many of my friends on Glen Meade are still with us. I know some of them are because we still stay in touch from time to time.

If nothing else, my father preserved some good memories of a time that has long passed, but which still puts a smile on my face when I think back to those days. It was only for a moment…JS

*****

I don’t think any of us could survive this world, if it weren’t for the soft and muted golden glow that the passage of time blesses us with. I know my childhood wasn’t nearly as idyllic as I now remember parts of it; in fact, I can still dredge up enough bad memories to give me pause right now — the truth is, my dreamy recollections don’t quite fit with Reality. But who cares?

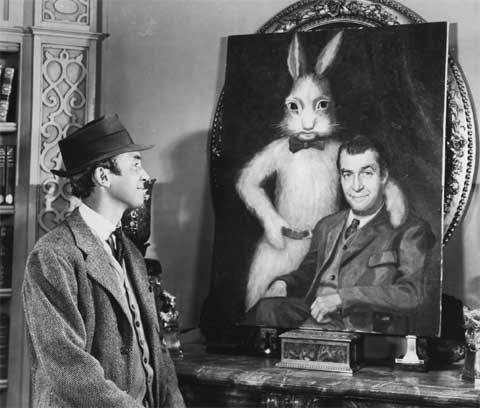

I remember the penultimate conversation between the always affable Elwood P. Dowd and a celebrated psychiatrist in the 1950 film, Harvey. Elwood claimed that his best friend was a six and a half foot tall, invisible rabbit named Harvey. Elwood claimed that Harvey was a pooka. Harvey was a magical being.

The concerned shrink shook his head and asked, “Mr. Dowd, isn’t it time you faced Reality?”

Elwood thought for a moment and replied, “Doctor, I’ve been fighting Reality for 35 years and I’m happy to say I finally won out over it..”

Maybe that’s the best kind of memory…the kind we want to have.

But I do know this. I know that despite the eternal ordeal of childhood, and the conflicts we all face at an early age with family and friends and strangers alike, we did have more time then to be kids. We may have been the last generation of children given the chance to create our own childhoods. Whatever ‘childhood’ is supposed to be now, it bears little resemblance to mine. Kids are tethered to organized activities and regimented play. Social media has turned us so far inward that most younger Americans don’t remember what’s beyond their cell phone screen. For many, playing outside now is more a threat than a privilege. Or an annoyance. Or a waste of breath and time. Doctors call it “nature deficit disorder,” and there’s scarcely a child growing up in Urban America today who isn’t afflicted by this disconnect between kids and the natural world.

I am so grateful I was spared this “illness,” and grateful that it hadn’t been invented yet. There were times when my frequent bouts with poison ivy and chigger bites, contracted out there doing intimate duty with the “natural world” almost got the best of me. The itching was so miserable, so much worse than getting punched in the face, that I might have welcomed the tradeoff. In the end, though, years after the blisters heeled and the swelling went down, I wouldn’t have wanted to miss a single itch.

HERE CAME ‘THE BOOMERS’

In the years after World War II the American Suburb was just beginning to dominate the landscape from coast-to-coast. A decade of economic hardship during the Great Depression and then four years of global conflict had finally ended. When the US Census Bureau did a head count in 1950, they found 151,325,798 citizens to call their own; by 1970 the number had jumped by almost 55 million. The Baby Boom Generation would flex its power in ways our parents never intended. It would change America forever.

My parents and I lived in a small downtown apartment off Bardstown Road that was owned by my father’s grandfather. Even though I was only three, I can remember our many long Sunday drives into the eastern half of Jefferson County, in search of a new home. In 1954, it was all farmland and forest, but all that was about to change. Nowadays historians refer to the Fifties as a quiet time, in the decade before JFK and the turbulent Sixties. But in terms of day-to-day changes to the American Landscape and the new booming culture that was about to swallow it up, it’s almost inconceivable that the land itself could literally disappear in a matter of years or even months. I could stand in the middle of Six Mile Lane in the autumn of 1955 and would think I was miles and miles from the nearest urban center. Ten years later, I could have been dropped in that same location and I would not have had the faintest idea where I was.

I’m tempted to compare the general growth in America to the New West Boom we see now, but it wasn’t the same. The migration west and to the suburbs of American Cities mostly included young veterans of World War II, who utilized the GI Bill to get a college education, young men and their new wives and growing families. But none of the vets was wealthy and the kinds of homes they sought were modest but well-built and within a price range they could afford. Eventually, almost all the dads in our neighborhood were young veterans of WWII. Some never talked about it. A few dads liked to regale us with war stories. Almost all of us wore, and eventually lost, the remaining fragments of their military uniforms and the artifacts of war that they brought home with them.

Our little piece of The American Dream was one of the first subdivisions to take root in east Louisville, Kentucky, more than 60 years ago. Glen Meade Road was a solitary finger of small two-bedroom brick homes in an area that had been farm land for almost two centuries. We were surrounded by dense woods and wheat fields, bottomless swamps and a pumpkin patch.

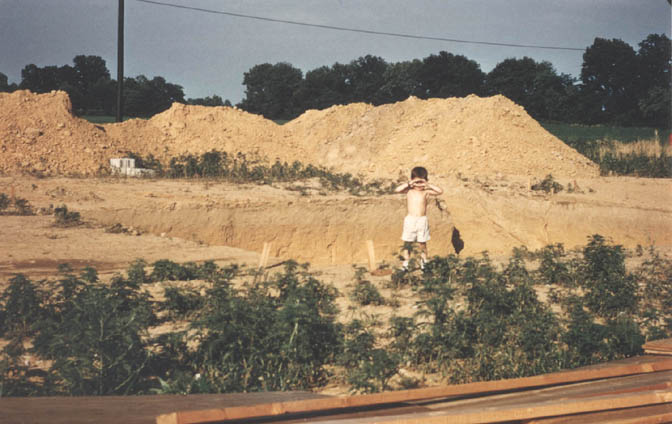

During the summer of 1954, we made weekly trips to Glen Meade to see how our home was progressing. The road itself was a mud hole that was last on the list of “things to do.” The houses went up rapidly. This was in the wake of Levittown and the birth of instant housing (or close to it). The homes on our street were basically of the same general design, but the builders offered a variety of options, like a bay window or a stairwell to the basement. My dad opted for the bay window, but otherwise tried to keep the price down. If I recall, we paid about $12,000 for our little two bedroom home.

3723 GLEN MEADE ROAD … LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

(I recently found my dad’s tax returns from 1946 to 1979. I inherited my tendency to squirrel away everything in my life from him. And I noted that when he bought the house, his annual income was $6,750 or about half the cost of the house. I wonder what the salary to home price ratio is in 2023)

A dirt road ran behind Glen Meade, on the edge of Old Lady Huntsinger’s field and my brother Jeff and I often waved to the hobos who made their way along the two-track path. They would jump off the freight train on Six Mile Lane and the Southern Railroad tracks, and make their way to the L & N Railway in Crescent Hill. In those days, talking to tramps didn’t seem like a hazardous gesture, even to my parents. Sometimes my mother even offered the tramps a snack or a sandwich. It was a tradition left over from the Great Depression, when out of work men often knocked on doors in search of something to eat.

*****

We moved across town in October 1954. I remember standing in the front seat between my parents (in the pre-car-seat era) and marveled at the way the moving van men had strapped my parents’ bed to the back of the big truck.

Once we settled in, my dad immediately went to work on the yard. At the time, our yard backed up to the hobo two track and a huge wheat field. My father planted a hedge across the back yard, maybe twenty feet from the fence. He told Jeff and me that we could do whatever we wanted behind the hedge, including digging a hole to China if that was our preference, but we were to leave from the front two thirds of the backyard alone. He had big plans. A friend of his, a man named Carl Raglan, lived in the far eastern part of our county, and the same kind of massive growth was happening there. Mr. Raglan told my dad that the builders were bulldozing a vast amount of woodland and were knocking down oak trees by the thousands. He suggested my dad go grab one before they were all gone. Clearly nobody else had considered the idea and my father worried briefly about getting arrested for tree theft. But he pulled out his shovel, as did I! And we went to work. He explained that we needed to maintain a ball of soil at the base and keep the root system as intact as we could.

This was no sapling. The oak tree my dad had chosen must have already been fifteen feet tall and cutting into the tap root was unavoidable. We…that’s pretty funny…HE managed to lift the ball of soil and roots and drag it over to a large piece of canvas. He watered it down with a canteen, wrapped the roots in the canvas, and somehow he dragged it to the back of our Ford Sedan and muscled it into the trunk.

Dad had only brought some twine to secure the oak and twice, in the middle of fairly busy intersections, the twine snapped and the oak fell onto the pavement. But it was a much smaller world back then. When the tree took a nosedive onto Brownsboro Road the second time, a man who knew my father was headed in the opposite direction and saw our dilemma. He turned around and came back to help. He had some heavy wire and c-clamps. The two men managed to secure the tree and we made it home without further incident. I helped dig yet another hole for the tree and he wedged the oak into the hole, added some water and manure and we filled in the remainder with the dirt. In 1955, our backyard had been farmland and it was incredibly fertile. If we went fishing, we never had to go far to find worms. Dad had planted forsythias all along the fence line and the worms seemed to love it there.

During that first winter, my brother and I were mostly restricted from venturing out beyond our yard. But soon children began emerging from Glen Meade homes, and the rule didn’t last. Almost every kid on that block was my age or my brother’s. Our fathers were the handsome young vets who had gone to war as babies and returned as men. Maybe it was because of our relative age, or maybe our dads grew up faster. I know that when my father was 21 years old, he was navigating a B-24 Consolidated Liberator, and flew 25 combat missions in the Pacific. It’s probably why my father’s generation had so much trouble understanding ours. Looking back on it, all these decades later. I appreciate his perspective considerably more than then. The difference is, back then, I thought I knew everything. Now I realize I know next to nothing.

THE WOODS

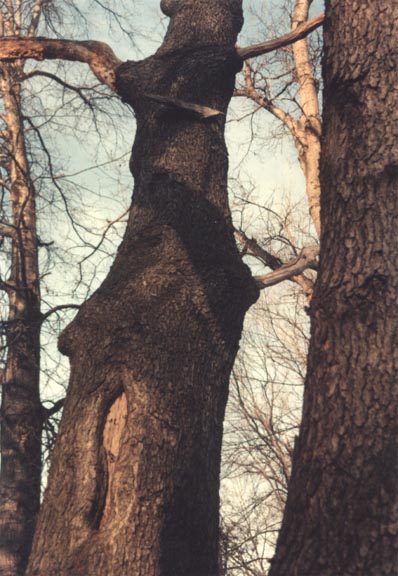

The following Spring, we watched anxiously to see what our transplanted oak would do. To my dad’s relief, the oak tree leafed out, right on schedule. Today, seventy years later, the Mighty Oak is still there. As summer came, we kids discovered “The Woods,” a thick line of trees that ran perpendicular to Glen Meade and bordered the east boundary of Miss Huntsinger’s massive field. There was a trail that ran the length of the Woods and soon we’d established trails and the more daring and enterprising of the gang gathered up some lumber scraps, bent nails and an old wooden handled hammer.

They started building tree ladders, one rung at a time. When they reached a fork in the limbs, the boys would build platforms where we could “goof around” as we liked to describe it, or drink smuggled Cokes from home, or just take in the scenery. We found odd slabs of limestone that were buried so deeply in the ground that our best efforts to remove them were futile. We figured it was probably an old boundary marker that dated back decades or maybe to the last century. Others thought the Indians had left it.

One complicating factor was the Woods and the Field itself. They didn’t belong to us. At the far end of Glen Meade, along the intersecting road just north, Hikes Lane, was the home of Miss Julia Huntsinger. The Family had owned much of the land near here and Miss Huntsinger, who had never married, lived alone in this massive 19th Century gray brick home. It was magnificent.

The field just outside her door produced a primary part of her income. But we kids failed to see the problem and endlessly tortured Miss Huntsinger as we ran amok in her winter wheat and trampled her crops. Her protests were futile, but she still terrified us when we saw that lone dark figure on the edge of her back porch.. She always wore a long black dress and she pulled her gray hair back in a bun. None of us had ever seen Miss Julia up close. We wouldn’t have recognized her if we fell over her. But still, when we saw that tiny whisper of a woman, in her austere black dress, she would raise her wooden cane and shake it at us. We could hear a faint noise, but her voice was too weak to carry. But it always worked, at least for a few days… just the sight of her made us run

Eventually my father turned me loose to explore The Woods at the end of the street (not to be confused with the Big Woods across the field). After all, I was over five years old now. I never felt so free in my very short life. I suppose I’ve been pursuing that kind of freedom ever since.

None of us kids realized how lucky we were at the time. Playing in the woods and building tree houses and hiding in the cane breaks and trying to find the bottom of the bottomless swamp was our world. It was all we knew and it was enough.

I knew every tree in those Woods on an intimate basis. We knew which ones were candidates for tree ladders and platforms. We knew which were good climbing trees. We usually knew which trees were wrapped in heavy poison ivy vines and if we didn’t, the hideous rashes that subsequently covered me from head to toe were our after-the-fact warnings.

More than once we went back to that piece of cut limestone, and tried to dig it up. It was at the far northeast corner of the Woods, and every time we saw it, we wished we’d brought our shovels. It was a constant source of mystery for us. Why a chunk of rock could have held our fascination for so long, I’ll never know. All little boys love a mystery I guess and this is the best we could come up with.

(Photo credit: University of Louisville Photo Archives.) For more information on the photo and its history, click here.

We wondered who’d put it there and wondered why and wondered how long it had been there. Someone suggested that maybe one of the original Kentucky pioneers had placed the stone obelisk in the ground. Maybe Daniel Boone or James Harrod or George Rogers Clark. Someone …Michael Pottinger? Timmy Kremer? David Kotheimer? David Mark Yarbrough? I can’t recall who else tried to dig it up but could never find the bottom of the rock. The mystery took on new dimensions.

The Swamp, in retrospect, was a godawful place. It was a slime-filled garbage dump more than anything else. And yet, for some reason, we felt compelled to wade through the swamp, in search of treasures and, at one end, the bottom. There were those among us who insisted that it was indeed bottomless and I would swear that on at least one occasion, I saw one of my buddies dive under the green slime and the garbage in search of it. That was more courage than I could muster.

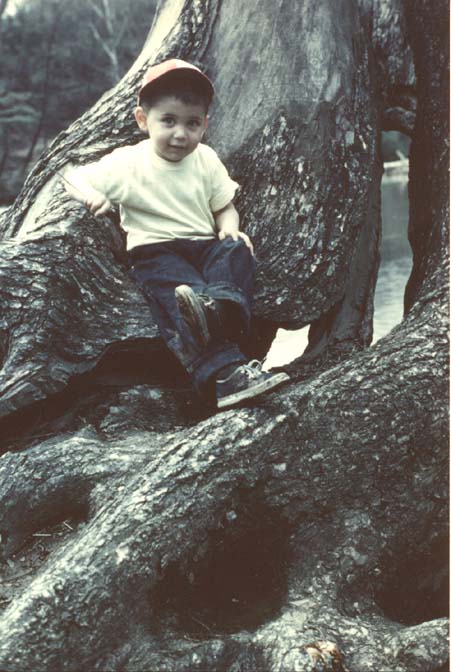

Before we even outgrew the Woods and the Swamp, however, Progress began to take them away from us. Even at six or seven, I had already learned that nothing lasts forever. It seems like our deepest held convictions and priorities often take root at an early age. When I was just three or four, before my brother came along, my parents took me to a special part of Cherokee Park in Louisville. It was called Big Rock and it was an easy wade for us from the park bridge to The Rock. But my favorite landmark was just adjacent to the bridge.

Years before, a massive tree had graced the banks of Beargrass Creek. But Time and the Elements had battered the old tree down, literally, to a stump, albeit a big one. A really big one. There were so many twists and turns, coiled limbs, and nooks and crannies in the trunk, I could have entertained myself all afternoon, every time we visited the park, just playing on that Stump.

Then winter came, and our visits to the Stump paused for a few months. When we went back to Big Rock in the Spring, the Stump was gone. Until that moment, I didn’t know that the world, or any small part of it, could change like this. The Stump was gone. I was livid. That morning my father brought along his new 8mm movie camera. Though it’s never been digitized and I haven’t seen the footage in decades, my dad clearly caught me in the act of throwing a fit because my stump was gone. I was good at pouting, even then.

THEN CAME THE EARTH MOVERS

On Glen Meade Road, the New World stayed approximately the same for a couple years. On the west side of the street, new roads and subdivisions were being built, and the pumpkin patch became a fading memory. But on the east side of Glen Meade, Miss Huntsinger;s wheat field protected us from further invasion. The Woods stayed intact at the end of the street and on the far side of the field, the Big Woods seemed endless to me. Once, just a few months after we moved to 3723, our neighbor noticed that the farmer had plowed a path from one side of the wheat field to the other. Mrs. Caldwell loaded my brother and me into a classic Red Flyer wagon and hauled us across the wheat, to the edge of the forest. We could see our homes now, all in a row. At the time, it was just us. That was okay. As long as that line of homes doesn’t get longer and longer, and bigger and bigger, and stretch to Infinity, I could, at age six, live with Life on Glen Meade Road. It was just the way I liked it.

Then, one morning, my father was shaving and I was stepping up on my box to use the toilet. With the box booster I could just barely see out the back window toward Miss Huntsinger’s field and the vast forest, the Big Woods, that lay on the other side. Every morning, I stared at those dense stands of trees and grapevines and poison ivy, and wondered what was beyond them. In a way, I didn’t want to know — I loved the mystery of it. I found such sights comforting to the eye and the soul.

This morning, however, I was shaken by an unfamiliar sight. Lined bumper to bumper on the far side of the wheat field, there must have been ten huge bright yellow earth movers and graders.

Oh the incongruity of it all!

I could not imagine what they were doing there and so I asked my father. He put down his razor and stared out the window with me.

“That’s construction equipment,” he said. “They’re building another subdivision, just like this one.”

“Just like this one?” I said. It never occurred to me that this had once been open land as well.

“But why do they need more houses?” I asked.

“Well, because there are more people who want to move out here, just like us.”

It wasn’t a very satisfying answer, even then.

“But what about all those trees? The Big Woods.”

My father shook his head. “I’m afraid most of them will be cut down, but I’m sure they’ll leave a few.”

Over the next few weeks, I watched the forest get ripped and torn and scraped and bladed until there was not a hint that a great and mysterious forest had ever thrived there. Homes went up, new families moved in who were just as oblivious to what had once been under their feet as we had been to the land under ours. It’s been like that ever since.

MORE PROGRESS…& MORE PROGRESS…&…

We watched the houses go up; our pastoral view out the bathroom window was gone forever. But I also realized that the new neighborhood hadn’t killed me. I was still breathing. There were other fields and “Woods” to explore. After a while, I grew accustomed to the subdivision scene across Miss Huntsinger’s field. At least the field was still there. And our Woods, the long line of trees and cane breaks held on and was still a place to escape to, even if the Real World was slowly closing in on us.

For the next decade, the changes happening around us became part of our normal routine. New home construction was constantly ongoing and in those days, theft of construction equipment or vandalism was unheard of. We’d explore the new half-built homes with thousands of dollars of tools lying on the floor. It never crossed our minds to steal them. We were looking for “slugs,” those quarter-sized steel discs that covered electrical outlets until an electrician popped them out and hooked up the wiring. We would find the slugs scattered across the unfinished floors and had no value, but we even worried that we might get caught taking the slugs and somehow get into trouble as a consequence.

When we first moved to Glen Meade Road, almost all the land to the south was agricultural. Even our street was a dead end for a year or two, until Glen Meade was extended another block and intersected Hunsinger Lane. From there, it was just a short walk to Six Mile Lane and farm country. At least that’s the way it looked for a while. The Southern Railroad still ran adjacent to Six Mile and a few buddies and I used to hike the tracks and cut across the farms to Jeffersontown (J-Town to us). It was nothing to walk ten or twelve miles in an afternoon and come home with energy to spare.

Our summer baseball games were still conducted in the middle of the street. Sewer grates were perfectly located to be Home Plate and Second. Water meter lids on the sidewalks became First & Third. We had to pause for the Donaldson bakery truck and the Erhler’s milk man to pass by for morning deliveries. Most of the traffic was composed of our families, so very few of them tried to run us over. But sometimes the more unruly of us would chuck a baseball (actually it was a rubber ball for street use) toward a passing vehicle with various and unintended consequences.

As the years passed and we grew older, and as the suburbs grew exponentially around us, some of the gang lost interest in the Woods and Miss Huntsinger and the Great Wild Beyond. Becoming a teenager is a terrible thing really. At 15 we walk away from the very experiences that half a century later, will give us our happiest memories. Growing up was not what it was cracked up to be.

Worse for me, when I was 13, my dad got a big promotion at Sears, where he had worked for almost 15 years. A new store manager, Mr. Diener, “saw something” in my dad and the step-up to “hard-line merchandise manager” almost doubled his salary. Suddenly that summer, my parents started talking about moving to a bigger home in the Highlands. Homes were still reasonably priced and after weeks exploring the streets near Cherokee park, they bought an old English Tudor home on Sulgrave Road. I had been infected by their enthusiasm and gave little thought to the cold reality of it all. I’d have to change schools and we’d move away from all our friends on Glen Meade.

I had been seduced by the prospect of a big bedroom with a window seat. Within weeks I was miserable. I was a kid who lived in the county, played in the woods, played baseball in the middle of the street and explored caves. The new school, Highland Junior High, was a city school. My classmates hung out at the corner drug store, caught the Blue Motor Bus downtown and wandered Fourth Street and the movie theaters. I was a duck out of water.

I suffered through the Autumn and into Winter. But in February I quit. I walked out the front door at Highland and went home; I hid in the attic. I refused to go back to that school. I went through a week from hell, but finally I convinced the city truant officer that I was not a threat to society. I just wanted to go back to my old school. In fact, Seneca High was just a stone’s throw from Glen Meade and when I triumphantly returned to my old school and many of my old friends, I felt like I was halfway home. For the rest of my life, I would always maintain a link to that street and that time in my life. Even today, I still have more friends from Glen Meade than I do in Moab…it’s true the oldest friends are the best ones.

EPILOGUE

Many years after the Stiles Family left Glen Meade Road, but still many years ago, in the summer of 1994, my old street had a reunion—the Glen Meade Road 40 Year Street Reunion. Some of the original residents were still there and had done a magnificent job of finding old neighbors from across the country. I flew back from Utah and parked in the huge asphalt parking lot that had once been Miss Huntsingers wheat field. My family passed between the Stevenson and Pottinger homes and stepped into a Time Machine. Few looked familiar but we were all wearing name tags. Repeatedly, we’d hear or utter the same astonished expressions — “Is that you? David Kotheimer? David Yarbrough? Jayne Novicki??? (who hadn’t changed at all). We rekindled old friendships and revived old memories and stories. More than anything we were reminded how lucky we were to have grown up with these people, at that special but strange time in America’s recent past.

It was one of those singular moments of my life that I will never forget.

Later, my brother and I walked down to what was left of The Woods. The wildness in them was gone, the cane breaks and grapevines and thickets of poison ivy were nowhere to be found. Only a solitary line of trees on a manicured lawn could testify to what had once been there. As we followed the edge of our diminished Woods, my brother looked up, gasped and grabbed my arm. He didn’t say a word, just pointed with his eyes.

A weathered piece of wood still clung to the tree trunk, secured with a bent and rusty nail. A remnant of what had once been a rung in yet another stairway to Heaven.

“So was it Timmy Kremer?” my brother sighed. “…or Michael Pottinger? Johnny Jones? Dougie Miller? Vic Gasperini? David Mark Yarbrough? David Kotheimer? Joe Bell? Ricky Nelson? Tommy Stevenson? Ken Bradley? Greg Caudill?

“I guess we’ll never know,” I said. “But one thing is for sure…when Glen Meade Road Boys built a tree ladder, we built it to last.”

(L to R) Jim Jr., Jim Sr., Jeff (Dad needed a little more sleep.)

“Hopelessly Clinging to the Past for Almost 35 Years.”

*****

Jim Stiles is the publisher and editor of The Zephyr. Still “hopelessly clinging to the past since 1989.” Though he spent 40 years living in the canyon country of southeast Utah, Stiles now resides with two cats, Rambo & Rascal, on the Great Plains. Coldwater, Kansas is a tiny farm and ranch community, where there are no tourists.

He can be reached via facebook. Messenger, or by email: cczephyr@gmail.com

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE VERY BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

$55 Each or Two for $100 (Free Shipping.)

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

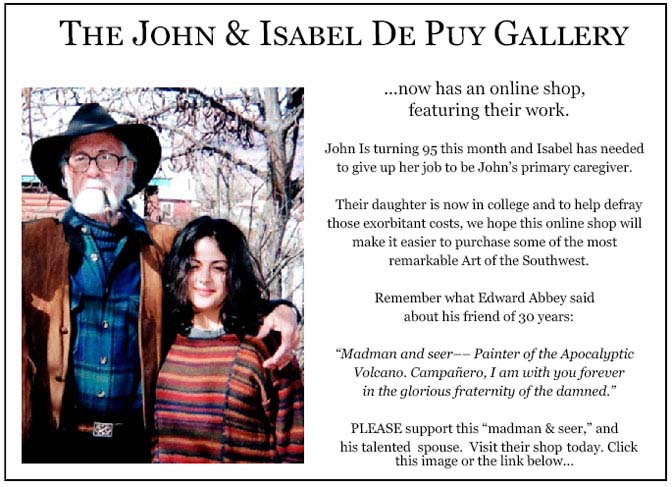

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

REMEMBER! I’D LIKE TO HEAR FROM ZEPHYR READERS. TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE VERY BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE.

Having grown up in two small towns, Nelson and Searchlight, NV, this story of your boyhood hits the spot! We were unfettered. We played under the light post until quarter ’til 9 when the lights blinked. That meant the electricity would be turned off in 15 minutes and we all scattered for home. Saturday night dances were held downtown and children attended, often sleeping under family coats on the benches which line the walls. Fathers danced often with very young daughters, whose feet were atop their Dad’s!! Everyone took part in the school plays. We had to raise our hand for permission to use the rest room which was a wooden structure outdoors. We vied to be the one to get to erase the blackboards at the end of the day! And thaks for the memories, Jim. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! Love, Donna

Thanks Donna. Your comments are always so sweet and happy. Merry Christmas to you.

I received this link from my sister Helen Salvate. Thank you for the wonderful story of our childhood. It sad to think that generations since have never experienced anything close to this with so many kids of similar age and upbringing. My mother’s house (3720) was the second to last to change hands with Mrs. Kremer being the last just a few years ago. I still cut down Glenmeade whenever I am near Hikes Lane. Thank you again.

Over the years I’ve shared so many memories with my fellow Boomers. Few people f us have had our wonder years so well documented. My family moved into our new home on Glen Meade the same year Jim moved in. Our house was across the street and Jeff stiles was my first best friend. It’s a joy that Jim and I are still in contact with each other after all these years. I look forward to sharing this article with my brothers and my sister. Thanks so much Jim.

Hi Dave. Thanks for your note. It’s hard to realize that right now, all those decades ago, the Glen Meade Road kids were all opening presents and, for many of us, headed to Grandma and Grandpa’s house. I had all four as a kid. I was lucky.

Enjoyed reading this Jim. Your Old Lady Huntsinger was Aunt Julia to me. My grandfathers sister. She made the best sugar cookies with pink, blue, and green icing. I know all the landmarks you mention. My how we can sculpt the land and change its communities. Headed to have Christmas brunch in Old Lady Huntsingers house in just a few minutes.

Hi Claude. I haven’t heard from you in years, but I was hoping you’d find this story. I will always remember our dinner at the old Sundowner in Moab and discovering our multiple connections to Miss Huntsinger and those “good old days.”

It’s amazing you’re about to have Christmas Dinner in that wonderful home and really happy it is still in your family. If you get a chance to take a few photos today, I’d love to see them.

Thanks again for checking in.

Damn good writing Mr. Stiles.

Thanks. It was sure a long time ago.

Yes, it was remarkably well-done.

Thank you for this! Your reminiscing conjures my own memories from the 50s and early 60s in Grand Junction. My parents were pretty cautious for the times and STILL I had SO much more freedom to explore the natural and “semi-natural” world, compared to children now … everything from catching frogs in the irrigation ditches half a block from our house to roaming (all alone!) over 100s of acres at my grandparents’ “farm” in Unaweep Canyon. My maternal grandfather was an amateur naturalist and my paternal grandmother was a very accomplished gardener — they taught me so much. All four grandparents in town and many aunts, uncles, cousins. And very much like your dad (also “Class of ‘46” Pacific Theater), mine was a prolific photographer, with his own darkroom, who documented these golden years. Always enjoy your writing and fabulous collection of photos. Again, thank you and best wishes.

Thanks. So many young men of The Greatest Generation shared those experiences. I can’t recall if I included it in the story, but almost all the dads on Glen Meade were young veterans of the War. All in their early 30s. All incredibly fit

There are so many things I wish I had talked to my dad about. He died in 2009. As a child of the Sixties, I was yet another Boomer who got crosswise with him. I remember a tv program where even Walter Cronkite’s children stopped talking to him over politics. Sometimes I think we Boomers really made a mess of the world.

Thank you Jim your writing always is a great start to the work week. It is difficult to go back to our childhood homes and see what little is left of what we knew. Thanks for clinging to the past! I hope you had a good Christmas.

Thanks Shannon. At the Glen Meade Road reunion, we got to go inside our old home at 3723. I was even able to explain a dark stain on the hardwood floor in the bedroom. It was caused by a diaper that somehow slipped under a dresser. It lay there for days until the aroma gave it away.

I knew we had something (well two things) in common…growing up in rural Kentucky (WKY in the 1970’s) and a fondness for the Colorado plateau…

Another great story from the Zephyr…!

Thanks Casey

The “greatest generation,” our parents, endured seismic changes in society, culture and technology that we can barely imagine. My pappy grew up on a farm in Paradox, Colorado and until the middle of the Century, his family could not afford modern equipment and so used draft horses and mules well into the 1950s. My parents were astounded by the achievements of the Apollo space program and modern calculators and fuel-injected engines. They were dismayed by social and cultural changes which, from their perspective, debased all the values and norms they upheld throughout their lives. I have a feeling that the boomers still remaining will live to see even more colossal and disturbing changes than those which our parents witnessed.

Nancy Jones, 3716 Glenmeade Rd. Looking in my rear view window I realize more each day how blessed I was to grow up on Glenmeade Rd. :0) The memories are certainly special and dear. Amazing how the bonds of friendship we form when we are so young remain the strongest. Thanks for bringing those wonderful memories to life for all of us kids who grew up on Glenmeade.:0)

I really enjoyed this return to childhood days. With your permission I would like to use the paragraph that begins with…”I know that despite…[and ends with] and the natural world.” .Our little community has a ‘mickey mouse’ newspaper for which I’ve written about my own experiences growing up. I’d like to use your paragraph, credited to you, as an intro to my own article. Thank you.