“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view..until you climb into his skin and walk around in it… until you stand in his shoes “

Harper Lee, “To Kill a Mockingbird”

I moved to southeast Utah 40 years ago, and from the day I arrived, there’s been a battle underway about public lands. The never ending fight has left both sides of the debate bloody and bruised…and it has irreversibly changed the landscape of the American West. Lately, the words have become harder and meaner. The Bears Ears National Monument Debate has brought it all to a very sharp and painful point.

While the origins of this fight have been with us for decades, and while both sides bear responsibility, I can only address the aspects of it that I am most familiar with. And with my own culpability.

More than ever, I am disappointed with the environmental community’s polarizing public lands diatribes that often play to emotions and ignore basic facts. I’m sure that some of their targets are justified, but the far-reaching collateral damage from their attacks has been mean-spirited and ultimately counter-productive.

To be sure, there are serious threats to public lands coming from a myriad of directions. Those lands subject to energy development and the extractive industries deserve and require serious, intelligent scrutiny and criticism.

Likewise, the continued destruction or looting of archaeological artifacts across southeast Utah and the West must end. The highest and best use of the government’s resources must be identified and utilized to prevent further damage. But are national monument proclamations really the best hope for protection? Has there even been an honest and open discussion?

Meanwhile, other threats to public lands and to the rural communities of the West are being ignored. Attention to them is being diverted by massively expensive propaganda campaigns, courtesy of corporate “green” America and the heavily bankrolled mainstream environmental community.

Most Americans who consider themselves environmentalists live and work in distant urban parts of the country and are unaware of all this. Few realize that many environmental groups are funded by some of the richest industrialists, venture capitalists and banker/financiers on the planet—and with little or no scrutiny from a mostly docile and co-opted mainstream media.

It’s hard to hope for honest, critical debate when it’s based on distorted or missing information, and disseminated in the most biased way imaginable.

I was once a a part of that side of the rhetoric. A participant. I contributed to this polarization and I’m not proud of it. Once before I admonished my readers and myself— to look in the mirror.

Now it’s time for me to look deeper. This article is about how I got from there to here, and why I believe we all need to take time for some careful introspection and scrutiny. For me, it’s personal, because I share in the responsibility.

In the beginning…

Four decades ago, I decided to make the canyon country of southeast Utah my home. I was a native Kentuckian, fresh out of college, and had been West for the first time as a kid on a family vacation a few years earlier. My decision to walk away from my old life and start a new one 1500 miles west, was for one reason only—I liked the scenery.

I didn’t head West for a job, though I had the vague notion that sooner or later I’d need one. I didn’t have family in Southeast Utah. Nor did I have friends there or even acquaintances. I knew a handful of people west of the Mississippi River. I was on my own, driven only by my love of the landscape.

At the time, that was an odd criteria for determining one’s long term future. But for me, it made perfect sense; subsequently, it would lead me to a lifetime of personal conflicts and agonizing hypocrisies.

When I arrived to stake out my home, Utah was a stranger to me in most respects, other than its topography and its established Mormon history. Early on, in fact, I knew more about the Church than its landforms. A couple years earlier, while working a summer job pumping gas in Jackson, Wyoming, I’d developed a crush on a young girl who worked at a local hamburger joint. She was unimpressed but I was persistent and I managed to extract a mailing address from her before the summer ended.

She lived in Ogden, Utah and was a good Mormon girl, but she inexplicably saw promise in me and the next summer, after many letters back and forth in the interim, she invited me for a visit. It became clear from the start, however, that she would require my conversion to the Latter Day Saints for the relationship to go anywhere. I agreed to listen to the missionaries and I still remember a kind gentle man named Brother Barlow who offered me counseling, but at the end of my visit, I knew I wasn’t going to convert.

But despite my reticence to become a Mormon, I left with good feelings about the LDS Church and respected and admired their faith and their love for each other. I had no reason to feel otherwise.

But when I arrived in Moab in the late 1970s, I unwittingly walked into a hornet’s nest of political, religious and cultural polarization, bordering on open warfare, between the “Old Westerners” and more specifically the Mormons who had first settled the area more than a century before, and the newcomers—like me— who’d been drawn to the canyon country by the sheer beauty of the landscape.

The issue then, as now, was public lands. The war over the highest and best use of that land. From the get-go, we were all required to “choose sides.” No matter what your views on public lands were, you were either “one of them” or “one of us.” The war continues today and into the distant future. There is no end in sight.

Some background…

In 1976, the same year I put down my Moab roots, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) was enacted;. The law “governs the way in which the public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management are managed.” Five years earlier, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). It was the first time the government was mandated to consider environmental issues in the administration of public lands and “required federal agencies to integrate environmental values into their decision making processes by considering the environmental impacts of their proposed actions and reasonable alternatives to those actions.” Thus, the birth of the “environmental impact statement.” And NEPA of course was the bi-product of 1964’s Wilderness Act.

For Rural Westerners, and in southeast Utah, nothing was ever the same. For a century these outliers had resided on lands once called, by a Mormon newspaper in 1861, “one vast contiguity of waste and measurably valueless, excepting for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians, and to hold the world together.” Now they were the center of unprecedented scrutiny and criticism, from the federal government, from an exploding new assortment of environmental watchdog organizations, and from a new and growing population of residents, including the likes of me, who had little if any interest in the communities or economies of the rural west, but a singular dedication to its landscape and natural environment. Those widely divergent priorities were bound to create conflicts.

In Utah, of course, most of the Old West was predominantly represented by members of the Church of Latter Day Saints—the Mormons. Consequently, in the Beehive State, the environmental opposition was dominated by strong, almost rabid, ‘anti-Mormon’ sentiments.

It never occurred to any of the state’s new arrivals that the reason the Mormons chose remote desolate places like these a century before was to escape the likes of people like us. Yet here we were, ready to tell the state’s longtime residents exactly what they were doing wrong with the land and how we could help them get it right. Imagine the reception that greeted such unambiguous declarations.

And yet, new laws were inevitable and needed. Post-World War II America changed the face of the American West and Americans moved here in stunning numbers. Demand for natural resources exploded as the economy of the United States experienced decades of unbridled, almost exponential growth. That growth created serious environmental impacts on those mostly unregulated public lands.

Many of the traditional residents of the West argued then and now that the lands should never have been “public” to begin with, that like states east of the Rocky Mountains, those public domain lands should have been mostly managed by the states themselves or sold to private enterprise. Non-westerners recoil at the thought. They believe public lands were specifically set aside for multiple use by all Americans. The fact is, they were the unsettled lands from which no one at the time could figure a way to make a living.

Coming to the Country…”The Ed Abbey & Cal Black Show”

I was ignorant to most of this as I moved to Moab. I’d come only for the land; I stumbled into a seasonal job with the National Park Service, and with a well worn copy of Edward Abbey’s “Desert Solitaire” under my arm for guidance, I staked my claim to my new home.

I met Abbey not long after I moved to Moab. He was quiet and understated and nothing like his books, and he somehow got me hired to illustrate one of his books, ‘The Journey Home.” I considered him a friend and became one of those early Abbey Groupsters.

But I gave little thought to the “other side’s” point of view. The insularity of my job as an Arches ranger and my own firmly entrenched views severely limited any inclination to examine a broader perspective. But that was my choice and I made little or no effort to seek out other opposing opinions.

* * *

With the battle lines now drawn, by the late 1970s, the Sagebrush Rebellion had firmly take root in Southeast Utah, led by the outspoken and sometimes provocative commissioner of San Juan County, Cal Black. Often it seemed like Black and his political nemesis author Ed Abbey were in a contest to see who could out shock the other, and in so doing, rally their own constituents.

In Ed Marston’s book, “Re-Opening the Western Frontier,” he describes a volatile meeting in April 1979 between Commissioner Black and the BLM over proposed closures of public lands. He cited a BLM document by staffer Janet Ross who reported that Black, “was the chief instigator of negative and occasionally violent feeling toward BLM in general, as well as its staff.”

Ross quoted Black saying, “I’m not a violent man…but we’ve had enough of you guys telling us what to do” He told the BLM, “We’re going to start a revolution. We’re going to get back our lands.” Ross’s report also claimed that Black made violent threats against government lands, property and BLM staff.

Black later denied making threats.

But in 1975, Abbey delighted his own followers with his combative and highly controversial novel “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” which advocated for the vandalism and/or destruction of everything from billboards and bulldozers to highway bridges and Glen Canyon Dam. The antagonist of the story was a pro-development San Juan County Commissioner named “Bishop Love,” though everyone knew it was Cal.

But in 1975, Abbey delighted his own followers with his combative and highly controversial novel “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” which advocated for the vandalism and/or destruction of everything from billboards and bulldozers to highway bridges and Glen Canyon Dam. The antagonist of the story was a pro-development San Juan County Commissioner named “Bishop Love,” though everyone knew it was Cal.

Abbey had no problem owning the radical, destructive tone of his novel. In a 1979 Washington Post article, Commissioner Black complained about real world monkey-wrenching, noting, “They’d put sand in gear boxes. Cut down highway signs. Over $200,000 damage was done to one construction company.”

According to the Post story, “Hearing this retold, Abbey’s craggy face breaks into a broad grin. ‘Good,’ he says. ‘How flattering. I admit I’d be delighted if somebody blew up the Glen Canyon Dam. I’d do it myself if I had the materials.'”

Abbey’s prose spared no one, from inept government workers to the Mormons (he often called them “Latter Day Shitheads”) to the local merchants (“There’s nothing smaller than a small businessman.”) Abbey loved to stir the pot, insulting friends and foes alike.

Both men later insisted they were just using words to make their respective points, but to followers on either side of the debate the super-heated rhetoric contributed to the tensions that spilled on to the political landscape. There were reports of threats by ranchers against BLM staff and threats to kill wildlife as well, though I was hard-pressed to find evidence that any of those threats were carried out. But recently “closed” roads by the BLM were often and illegally “re-opened” by angry locals who resented the government’s administration of lands they’d always felt were their own. The problem was that suddenly, many new citizens of a different ilk were making claims too.

Legions of young vocal environmentalists who had recently moved to Utah were regular and noisy attendees at public wilderness hearings. Before cable tv, the internet, and smart phones came along, environmental public hearings and meetings were Moab’s most successful form of entertainment.

And incidents of vandalism, especially to road and mining equipment, cut fences and even unexplained cattle deaths increased across the canyon country. Many Abbey-inspired monkey wrenching efforts were token gestures by young men with raging hormones, eager to impress a girl, though sometimes the damage was more serious.

The Sagebrush Rebellion, and the animosity between the longtime locals and the federal government, reached a crescendo on July 4, 1980, when Grand County commissioner Ray Tibbetts fired up a D9 CAT and drove it into Negro Bill Canyon, an area that had recently been designated a “Wilderness Study Area” and closed by the BLM.

My parents were visiting from Kentucky that day. I recall the long lines of cars and pickups that followed Tibbetts to the site, lights on and horns honking. I explained the “event” to my father who was a staunch conservative. He kept saying, “This is really something. The people are angry,” and declared “I think Reagan is going to beat your man Carter.”

I laughed. “Reagan? No way.”

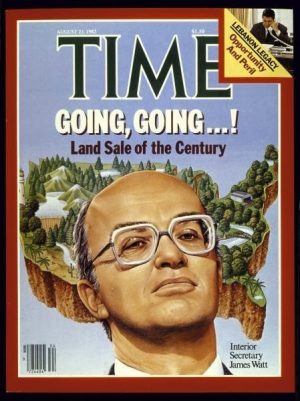

Ronald Reagan did win of course, in a landslide, and appointed one of the most controversial Secretaries of Interior in recent memory. James Watt once declared, “I don’t like to walk and I don’t like to paddle.” He had no use for environmentalists and always favored development over preservation. Watt became the poster bad boy for environmentalists and ultimately created a fortuitous moment for their movement.

Marketing Watt as the ultimate antagonist— the Darth Vader of the Environment— proved to be an unprecedented windfall for the mainstream environmental community. The rhetoric ramped up as well.

Marketing Watt as the ultimate antagonist— the Darth Vader of the Environment— proved to be an unprecedented windfall for the mainstream environmental community. The rhetoric ramped up as well.

And so, in the 1980s, the public lands debate got uglier and the words got meaner. From the conservatives, the talk got hard and threatening. Federal employees were careful not to “talk shop” at the local bar, for fear of being overheard.

Incidents of tires being slashed in the backcountry on vehicles with ‘wilderness’ bumper stickers became common. But so did stories of more monkey wrenching–from burned out line camps to sand in road grader crank cases.

And “my side” of the aisle became experts at ridicule and derision. Environmentalists decided the best way to counter the opposition was to mock every aspect of the Rural West, from their chosen occupations and political leanings, to their lifestyles and religions. Nothing was too sensitive to ridicule and I was just as guilty as any of my peers. For a while, I even made a career out of it.

And yet somehow, I thought I could have it both ways. I personally liked and admired a lot of the “old westerners” and sought their friendship; yet I was just as obnoxious as any of my “group” when it came to criticizing their opposition to our way of thinking.

Joe Stocks came from one of the Moab Valley’s oldest and most resilient families and had managed to eke out a living and survive in one of the most remote parts of the desert southwest. Joe had also served honorably in Vietnam and when he rose to speak at a wilderness hearing in Moab, Joe made it clear he thought certain forms of “recreation” were created by mad men. He noted that he’d “carried a sixty pound backpack in Nam for two years” and he couldn’t imagine anybody in their right mind wanting to put themselves through such agony.

He was almost laughed out of the room by the hoots and hollers of the county’s new “green” residents. I was laughing too. And yet I’d also just met his mother, Verona Stocks, one of the dearest and kindest women I’ve ever known. Eventually she’d give me permission to print her memoirs in The Zephyr. Later, I’d meet and befriend Joe as well. But at the time, I didn’t grasp my own contradictions: I was fascinated and impressed with the history of the place I now called home and wanted to honor those people who created that history. And yet, I was willing to do what I could to end the way of life that made them who they were.

The contradictions were endless. I loved to wander the Yellow Cat mining area north of Arches National Park. In the 70s the area was full of ghosts. Old cabins and Model Ts dotted the badlands of Mancos Shale. One ancient shack was built out of old surplus wooden ammo boxes. I found a derelict school bus out there. Then, after an absence of a few years, I went back and discovered that all the old trucks and cars were gone.

To me, they’d removed a piece of history. Furious, I called the BLM office in Moab to complain and they were as shocked at me as I was with them. “We’re sorry Mr. Stiles…we thought people like you would be delighted. We assumed you’d be happy to see all the old wrecks hauled away and the country restored to its natural state.” He might well have added, You guys shut down the industry. Now we’re getting rid of the evidence.

As an Arches ranger, I sometimes bumped into local rancher Don Holyoak. He had an allotment in Seven Mile Canyon and once he showed up on horseback as we finished building a drift fence across the stream, which was supposed to keep his cattle out of the lower canyon.

We knew eventually his cows would be pushed out of the park completely and he took a dim view of the new economy of mountain bike recreation. “It makes no sense,” he complained, “pedaling your legs off to give your ass a free ride.”

I agreed and took a dim view of the new mountain bike phenomenon. I wanted to be a friend of Don Holyoak but everything else about me warned him to stay clear. After all, I was the park ranger who recently notified headquarters that Holyoak’s cows were trespassing once again, wandering the park road near Balanced Rock.

And I was Ed Abbey’s friend. His annoyance with cows was well-known and Moab’s environmentalists laughed heartily when Ed fired off his 1987 letter to the Times-Independent, complaining about the “stinking bovines” on the La Sal Mountains.

His well-publicized 1985 rant about “welfare ranchers,” delivered in a speech called “The Cowboy and his Cow” to the Montana cattlemen’s association did little to improve his standing. “If you don’t see them, you’ll smell them,” Abbey ranted. “The whole American West stinks of cattle.” As for the cowboys, Abbey advised that they “find some harder way to make a living. Like the rest of us have to do.”

Yet, Abbey seemed genuinely stunned when he lost rancher friends as a result. Sometimes, I got the impression Abbey never expected anyone to take him seriously. And I wondered if it’s because he rarely did himself.

But his followers sure did and literally, most of the time. Abbey’s books became a template for the growing population of pro-wilderness, anti-multiple use advocates who first came to visit the canyon country and later became the face of the New West. If a relative few of them took up his call to monkey wrench, almost all of us embraced his rhetoric.

Rural Westerners became the never ending butt of cruel jokes and and derisive insults. Back then, I made my fair share of them. Mormons in particular were singled out for abuse, and not just just because they failed to meet the supposed high standards of their environmental critics—everything was on the table. Their specific religious beliefs, including the size of their families, their abstinence from alcohol and tobacco, and even their underclothes were subject to ridicule.

Rural westerners were collectively, in the eyes of New Westerners, ignorant, backwoods rubes, insular morons who were incapable of seeing the enlightenment that environmentalists so anxiously wanted to impart on them, and which in return, the Old West so stubbornly and foolishly rejected.

Rants against ranchers and cowboys descended to levels that were classless and crude–and not, in my view, what Abbey intended. While I worked at Arches, I remember one of my fellow rangers making fun of a local rancher, commenting on the man’s lack of a formal education. Sitting nearby was Dutch Gerhardt, a heavy equipment operator for the Park Service and a great friend of the legendary Park Service superintendent, Bates Wilson. Dutch had come to Utah with the CCC boys in the late 1930s, had married a Mormon girl and had been a cowboy for years. Lean and mean and still tough as nails at 65, finally Dutch had heard enough. He walked up to my young friend and put his lined and weathered face about six inches from my fellow ranger’s nose.

Dutch squinted and said, “You know the difference between cowboy boots and engineer boots?

My friend shook his head nervously.

“Well,” Dutch replied, “With engineer boots, the shit’s on the inside.” Dutch spit on the ground and walked away.

I think Abbey would have savored the moment.

In his last decade, Edward Abbey began to doubt his own lock-step legions of fans. He expressed alarm over illegal immigration, advocated for a strong militia along the Mexican border, and was always a strong proponent of the Second Amendment, much to the chagrin of his liberal followers. And just months before his death, he railed against what he called “chickenshit liberalism,” writing in his journal that it was, “exactly the kind of cant and sham and hypocrisy, intellectual dishonesty and moral cowardice, that has turned me finally against ‘liberalism’ in general.”

But in 2017, many of his fans have managed to filter out the “bad Abbey” parts, and reduce the body of his work to some pleasing sound bites, leaving them with exactly the kind of revisionist rhetoric that coincides with their own values.

Abbeyphiles continue to call him a “prophet” (Abbey’s favorite self-moniker was “entertainer”). And his diatribe against ranchers was recently immortalized in leatherette and sold as an Abbey collectible from Moab’s own Back of Beyond Bookstore.

Ed Abbey and Cal Black remained the lightning rods of the public lands war into the late 1980s. But then, almost simultaneously, both men were struck down. Black announced he had inoperable lung cancer, a death notice Black and his doctors attributed to uranium exposure. He had worked the mines in southeast Utah, going back to the 1940s.

Abbey had suffered from a variety of health issues for a decade and had once been mis-diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Few knew of Abbey’s declining health and when he died on March 14, 1989, at age 62, we were stunned.

A few months later, Cal Black announced his retirement from the San Juan County Commission. The Deseret News reported that “the 60-year-old commissioner has inoperable cancerous tumors in his right lung and clavicle.” Clearly Black was dying.

But asked to comment, the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance could only complain, “He single-handedly has probably represented most of what the environmental community doesn’t like in public officials, which is insensitivity to the environment…It’s a shame Edward Abbey isn’t around to comment on Cal Black’s political obituary,”

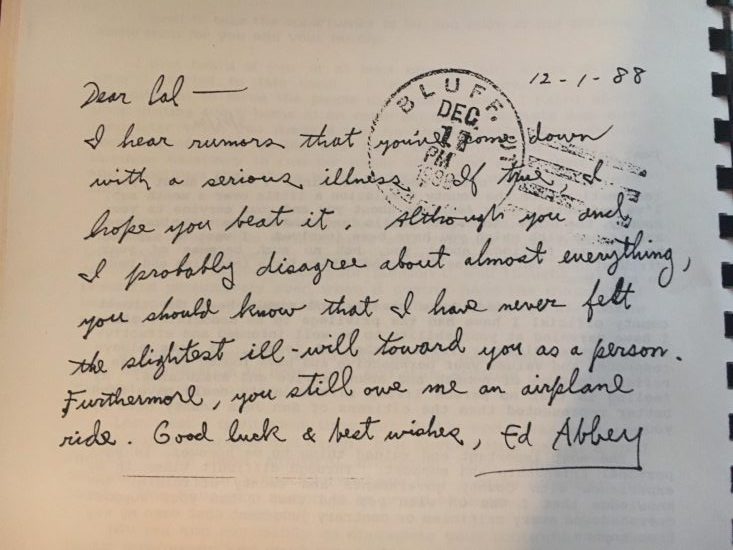

In fact, Abbey did have a chance to comment. Though dying himself, Abbey learned of his old adversary’s terminal cancer and on December 1, 1988, penned a note to Cal. A few days later it arrived in Blanding. Abbey wrote:

Dear Cal,

I hear rumors that you’ve come down with a serious illness. If true I hope you beat it. Although you and I probably disagree about almost everything, you should know that I have never felt the slightest ill-will toward you as a person. Furthermore, you still owe me an airplane ride. Good luck & best wishes.

It was probably not the sentiment SUWA and other environmentalists might have expected. But for Cal and Ed, the war was over. Cal Black died on May 11, 1990. He was only 61.

Post Abbey/Black…The Zephyr’s Complicity…

In the 1990s, despite the sudden departure of its favorite spokesmen, the rancor between the Old and New West was just getting started. And I helped.

The first issue of The Zephyr went to press on March 14, 1989, the same day Abbey died. In that premiere edition, I proposed that The Zephyr be a sounding board for many ideas and beliefs and I did actively seek writers with whom I disagreed. But from the get-go, it was clear that I had an agenda. I can look back at those first few years now and see how thinly transparent my efforts at “balance” really were. And when I decided to give the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance two free pages of space in each issue, in the form of the “Canyon Country Watchdog,” I sacrificed any chance I might have had of being considered evenhanded. The one-sided views from them, and often from me, were too self-righteous to ignore.

SUWA’s Watchdog was a never ending litany of perceived threats against the canyon country and there’s not a doubt in my mind that SUWA sincerely regarded each of them as one more nail in pristine SE Utah’s coffin. But after several years of reporting, even I started to wonder if there was a single acre of ground left that they believed hadn’t been degraded or destroyed by an oil well, a cow or an ATV…the picture they painted for Zephyr readers came close to apocalyptic. Still, I kept printing them without question or scrutiny. The responsibility lay with me.

And the sarcasms and smirks, from them and from me (and sometimes working tag team-style) were a regular part of our schtick. Once, in 1993, Utah’s newly elected Congressman Bill Orton spoke out on SUWA’s wilderness plan, which at the time only encompassed 5.7 million acres (it’s now at 9.6-10).

I didn’t follow the Congressional Record closely but SUWA did, and one day I got a call from a staff member, who saw a Stiles cartoon in the making, based on Orton’s comments. Though a Blue Dog Democrat, Orton didn’t think much of their wilderness proposal and for the record stated that he’d, “rather be dragged naked by his tongue through a cactus patch than vote for this bill.”

SUWA wondered if I’d be interested in visualizing Orton’s comments and I was delighted. Though I knew nothing about the congressman or his views on any other subject, I willingly put pen to paper and produced the cartoon. SUWA loved it and I was pleased as well. I didn’t give it another thought.

But two years later, as the wilderness debate heated further, Rep. Orton came to Moab for a town meeting. I showed up, tape recorder in hand, ready to capture his next faux pas. To my consternation, Orton was articulate, warm and friendly. Even though I still disagreed with him on many points, I found myself thinking, “I really don’t hate this guy.” What touched me most was the love he clearly showed for his family. The congressman had brought along his wife and his new baby, which he proudly held up for all of us to admire. He was the biggest admirer of all and I got the impression he’d rather talk about life as a father than as a politician. That evening changed me, although a recent review of old Zephyrs tells me I had a long way to go.

But in my slow, plodding way, I had already made some effort to at least acknowledge both sides of the debate, if only privately. In 1992, The Zephyr was actively engaged in trying to stop a proposed 87 mile, multi-million dollar Book Cliffs Highway, from Vernal, Utah to Interstate 70. Its proponents, mainly the Grand County Commission and Road Board, believed the paved highway would increase oil and gas production in the area by providing easier access to I-70.

But, to gain more support, they also promoted it as a new tourist highway, which was always my greatest fear. The Book Cliffs Highway would create a perfect funnel for travelers coming south from Yellowstone National Park to the Grand Canyon. It looked like a nightmarishly perfect tourist storm to me.

County Commissioner David Knutson supported the road and his father was on the road board. He believed that the highway would vastly increase oil and gas revenues and subsequently enhance Grand County’s tax base; I had never given the matter of taxes much thought, though I did believe the monies being diverted for the road could be better utilized by other Grand County services like the hospital and the landfill.

One day, Dave invited me to ride with him to the Maze District of Canyonlands NP. His family business hauled water to the park and because it’s a very long ten hour drive over rough roads, he thought he could use some company. Even me. For mile after mile, we argued about the road. I feared the changes it would bring to Moab and Grand County via tourism. He was concerned about the schools.

“Do you guys even understand how a community works?” he asked.

We moved beyond the matter of the Book Cliffs Highway and talked about rural communities in general. In 1992, like now, many rural counties and communities were struggling. Communities differs in scale, but they all have the same basic requirements to be a city in the first place.

Every town, large or small, must provide basic services that many of us take for granted. From its schools and roads to its cemeteries, from law enforcement to fire protection, from weed control to mosquito abatement, from patching potholes to trimming trees, there is a lengthy list of needs that every community must deal with and pay for.

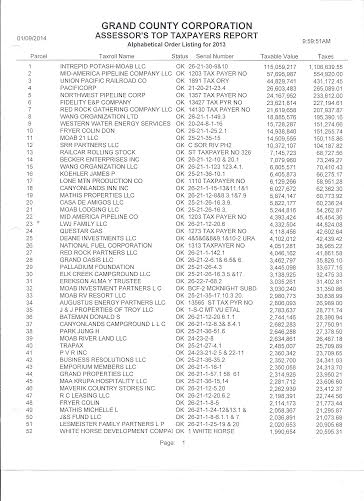

That was Knutson’s motivation. Later, he pulled out a list of Grand County’s top tax payers. Almost all of the Top 50 were some kind of company involved in energy development and extraction. (Twenty years later, the tax list hadn’t changed much–despite the tourist boom, Grand County’s #1 tax payer in 2014 was the potash plant, which contributed more than a million dollars a year)

“Stiles,” he complained, “All of you environmentalists always want to think we’re evil because we support industries that you think are bad. You think oil wells are bad so you think we’re bad. But that’s just not fair. We want to have jobs and pay our bills and maintain a nice town for our kids…how does that make us evil?”

“Remember the toxic waste incinerator that you guys stopped back in 1989?” Knutson added. “You all made Jimmie Walker out to be Moab’s Darth Vader because it was his idea….Well, it’s the same thing. He thought it would be good for the town, and help us keep the county alive…how can you hate him for that?”

Thinking now about the incinerator and its health risks and being reminded of Cal Black’s early death from the uranium mines, it does give me pause. Early on, many men who worked the “dirty jobs” had no idea of the risks they were taking with their own lives, but eventually the truth became harder to conceal. Consequently, the workers received better pay for those risks.

But many of us are bewildered why anyone would accept those jobs, regardless of the pay, knowing the adverse consequences they’d have to face. But maybe those of us who don’t ‘get it’ were never that hungry for work or decent wages to feed their family. When I think of the man or woman who would knowingly sacrifice their own health in the long run, so that they could better provide for their children, I realize it’s a kind of courage and nobility that escapes a lot of us.

And again, it comes back to motivations and priorities. These contradictions and complexities were never considered by the many New Westerners who moved to Moab and southeast Utah for the scenery and nothing else.

The Book Cliffs Highway was stopped in 1993, and Knutson left politics, became an LDS bishop, and maintains the same shop that he and his dad ran together, decades ago. I didn’t see Dave or his family for twenty years, but one day in 2015, I dropped by his place on the South Highway and we spent several hours recollecting, commiserating and confessing. It was Memorial Day weekend and outside, just yards away, holiday traffic was backing up for miles. It would prove to be the first of many Moab holiday gridlocks, where the overwhelming number of visitors literally shut down the town. The highways were paralyzed and eventually, park managers closed Arches National Park…a first.

Dave and I talked all afternoon over a six pack of Diet Mountain Dew, Bishop Knutson’s beverage of choice. I admitted that back then, I hadn’t considered the economic factors as carefully or as sensitively as I should have. Likewise, he confessed that he thought I was crazy back in 1992, when I insisted tourism could ruin our town. “I guess there are some things,” he said, “that I didn’t see coming. And there were other things that got past you…

“And now,” Dave paused and glanced out the window. “…here we are.”

Stay tuned for: ” STANDING IN THE OTHER MAN’S SHOES…Part 2—

The Bears Ears Debate—Is it Racist to Oppose the Monument? Are Rural Mormons to Blame for…Everything? …A Counter-Productive Environmental Strategy…

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

![]()

FYI: Bill Orton’s widow, Jacquelyn, is running for the Utah House District 27 seat that’s being vacated by Rebecca Chavez-Houck.

https://www.deseretnews.com/article/865681089/Jacquelyn-Orton-announces-plan-to-run-for-Chavez-Houcks-seat.html

Great article Stiles. As a new BLM’er in Hanksville in 1978, transferring to Moab in 1982, I got to see all this up close for 30+ years. Four years on a County Council was pretty much more of the same! Your story was a trip down memory lane, lots of memories.

Thanks for sharing the transformative metamorphosis you went through. My thoughts changed considerably over the years too, living in these communities, getting to know the people and the families, seeing the efforts they had to undergo to craft a living surrounded by a sea of federal lands they had no authority over.

I wish more of the “newcomers” would open their minds, and quite frankly their hearts, and figure out a way THEY could integrate into these communities, instead of feeling so compelled to change the communities to suit their desires.

As you are a Kentuckian I’ll leave you with a quote from a fellow famous Kentuckian, Muhammad Ali, “A man who views the world the same at 50 as he did at 20 has wasted thirty years of his life.” Glad you haven’t wasted the last 30 years of your life ( well mostly I suspect)! Looking forward to the second part.

Well done. It interesting how as we get older we come to the realization that everything isn’t as clear as we once thought. There is another side of the story. Thanks for your thoughts. Cheers! Mitch

remember in one of the star trek movies Kirk says to someone puzzling over Spock’s seemingly-strange behavior: (to the effect of, “back in the hippy days”) HE TOOK TOO MUCH L D S.

Somewhat of a refute of the Muhammad Ali quote (as shared by Lynn previously) — sometimes I wish I still viewed the world at 50 (or, in my case, a tad more seasoned) as i did at 20. I’m still, basically, an optimist, tho’ most the time i can’t explain why — especially to myself.

Oh! thanks (again) for the research and recollection of the changes of your view(s) of the world — especially detailing the peeling-back-the-layers-of-your-insights ~