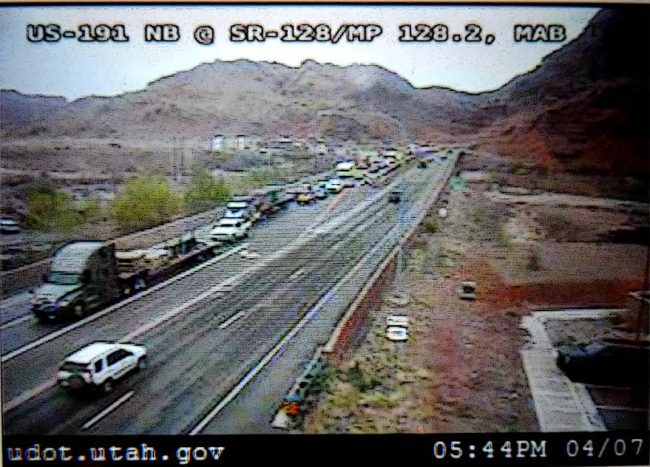

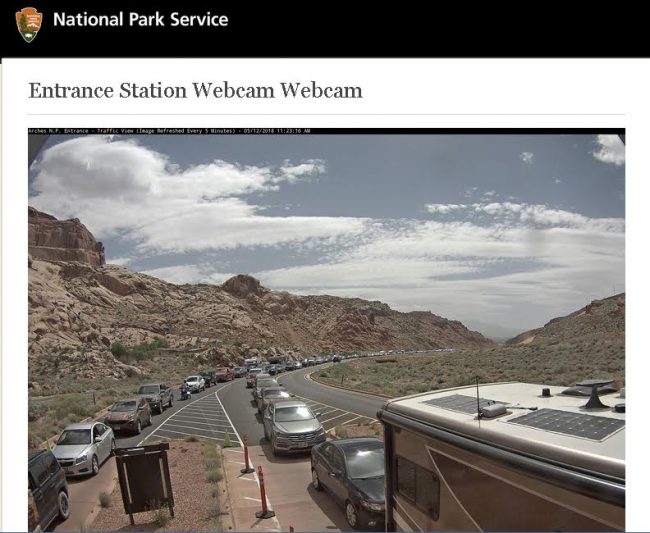

I have recently learned to remotely keep track of traffic flows at Arches National Park and the Moab area via web cameras at the park entrance and along US 191 as the tourists flow in and out. I’m a Luddite at heart, but I admit that using technology to see how insane the Industrial Tourism Industry has become in Moab —without actually having to be there— gives me some kind of perverse satisfaction.

And so on successive weekends, and even midweek, I’ve screenshot and posted the “Madness that is Moab” on our facebook page. Most Zephyr readers share my revulsion of the mere sight but not all. In fact, I’m beginning to realize that those who share my views (“Oh we merry few”) are rapidly becoming the minority. Or even more accurately–we are becoming anachronisms in our own time.

While many “Old Moabites” and more traditional environmentalists like myself can only shake our heads and be thankful that we saw the country decades before it came to this, others don’t seem to get it at all.

One avid mountain biker wrote in part:

“… can you provide a link to your commentary article outlining what problem you are specifically trying to point out in these Moab traffic photo posts?… people who want to experience our wonderful outdoor places should be encouraged, not shamed. Experiencing nature is great for everyone, right?”

He didn’t understand the problem. In fact, he didn’t think there was a problem. We were viewing the same photographs of traffic backing up a mile or more. We both knew that the line had been like this for hours, and that ALL of those vehicles and their passengers were now crammed onto 18 miles of pavement and sardined into trailhead parking lots.

I found myself recoiling at the sight of it…he could not understand what I was complaining about. Despite the traffic this is what he still maintained is “experiencing nature.”

And THAT is the point of this essay.

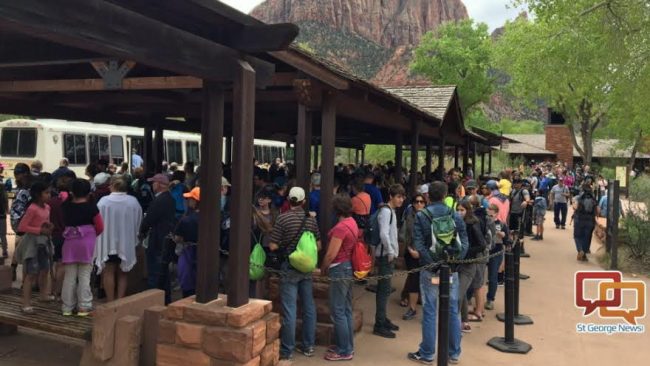

Neither the biker’s comments, nor the screenshots from Moab are unique. Go to Jackson, Wyoming, the gateway to Grand Teton and Yellowstone Parks, or to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, or Estes Park, or Springdale, Utah and the entrance to Zion.. Go anywhere in the scenic American West lately and these are the kinds of crowds we can all expect to find, especially during the “tourist season” (which gets longer with each passing year as the travel industry spends millions to promote these areas and to “build up the season’s shoulders.”).

For me, there is an obvious question that comes to mind when I see these lines of cars, or the hordes of tourists trudging along a designated trail, or waiting endlessly for a parking space, or even standing patiently like sheep to board the “solution” to this mess—the celebrated shuttle bus

When I see this crush of humanity all trying to get away from each other to “experience nature,” to allegedly “get away from it all”—LIKE THIS, I have to ask myself:

‘Who in their right minds would subject themselves to this kind of excruciating torture?’

And the answer of course is—apparently just about everybody.

Offering empirical evidence—numbers, facts, even photographic documentation— of the out-of-control recreation industry fails to stir any kind of righteous indignation among “New Recreationist/ Environmentalists.” As long as they can all get inside the park, find a suitable scenic backdrop, snap a few pics on their smart phones to post on their facebook page, almost everyone seems happy.

How did real wilderness, and the values we believed were its critical and most indispensable components, end up in this shamefully degraded state? When did solitude and peace and open space become so marginalized that most people forget they exist…or even need for them to exist?

There were forces and movements at play two decades ago, that help us understand how we got from there to here.

First, it became clear in the 1990s and early 2000s that there was a significant change in the way our children were being raised, and that it was having a profound effect on their views of the Great Outdoors. For reasons I’ve never quite understood, the Baby Boomer Generation, once they assumed parenthood, seemed to forget the free and unfettered content of their own childhoods and instead became the masters of “organized recreational activity under controlled conditions.” Kids didn’t go to the Woods anymore. They took a pre-screened, heavily supervised guided tour of it. Soccer moms were born.

The disconnect between younger Americans and the natural world has been a noted and growing concern for a couple decades now. Author Richard Louv’s 2005 book, “Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder,” gave a name to the notion that kids no longer have any connection to Nature or to independent thought for that matter.

A review of the book in the NY Times noted that Louv:

“…describes an environmental ennui flowing from children’s fixation on artificial entertainment rather than natural wonders. Those who are obsessed with computer games or are driven from sport to sport, he maintains, miss the restorative effects that come with the nimbler bodies, broader minds and sharper senses that are developed during random running-around at the relative edges of civilization.”

The problem had existed for years before Louv’s book came along. But while some consider the almost desperate need to reverse this trend, others accepted the changes as unavoidable and some saw a way to embrace it and even exploit it. In 2004, I came across a report from an organization called “Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Units” or the CESU Network.

It describes itself as:

“…a national consortium of federal agencies, tribes, academic institutions, state and local governments, nongovernmental conservation organizations, and other partners working together to support informed public trust resource stewardship. ..including 425 nonfederal partners and 15 federal agencies across seventeen CESUs representing biogeographic regions encompassing all 50 states…The CESU Network is well positioned as a platform to support research, technical assistance, education and capacity building that is responsive to long-standing and contemporary science and resource management priorities.”

At a joint meeting of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains CESUs in April 2004, the topic was “Tourism Break-Out.” Here are some excerpts:

“Regarding tourism and tourism patterns in the West, the key issue is CHANGE – including changes in visitor groups, desired activities, desired experiences, tourism patterns – and how these changes will influence federal land managers – in the short and long term.”

This section particularly moved me:

“A recurring discussion theme was that it’s important to have young people involved in projects – because they are a primary age group that we need to know more about, and a group that can help federal agencies recognize future needs. CESU collaboration with universities provides an excellent way to reach this group of young researchers/project team members.

“It is critical for federal managers to understand how different groups want to use federal lands and, in the same way, how they value federal lands. For example, how do BLM and/or NPS lands ‘resonate’ with different age groups or ethnic groups – and what will this mean for the long-term support and interest in their federal lands.”

Among the topics associated with this idea were:

“The changing values of generations regarding parks – what one generation values in a park (such as solitude) may be less important to another generation (that may be more interested in extreme sports).

“Use of Ipods, GIS, computer technology and how that can assist in site interpretation. Issue of “Receptivity.”

“Great potential for partnerships with outdoor recreation outfitters, suppliers, clothing manufacturers, etc., who already know a great deal about our federal land visitors and have a strong handle on how people are using that land.”

CESU’s observations could not have been more telling. Since then, any effort to promote a pro-wilderness/pro-nature experience often includes high-tech, high-risk physical activity and a financial connection to the recreation industry…

* * *

In the very early years of this century then, this was how a “consortium” of government, academic and NGOs viewed the future of our national parks. All the “great potential for partnerships” that CESU sought have come to pass—and then some.

Almost simultaneously, environmental organizations across the country were re-thinking their wilderness strategy. “The Wilderness Mentoring Conference of 1998″ was a gathering of self-proclaimed “mentors,” professional environmentalists active in organizations that reached from Washington DC to Alaska. This relative handful of New Environmentalists were frustrated by the movement’s lack of progress in pushing and passing wilderness legislation across the country.

Its participants came from national and regional environmental organizations coast-to-coast, and included representatives of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA), including its then-Executive Director, Mike Matz.Matz who presided over the conference as mentor-in-chief.

While the organizers of the event paid tribute to the wilderness activists who had come before, clearly the purpose of the meeting was to propose a new approach. “Although it is important to pioneer new wilderness strategies,” the report explained almost as an afterthought, “we must do so with knowledge of what has come before.” With that token nod to the “importance of history” and to the “philosophical and political contexts” of the wilderness movement, the conference explored the new territories of salesmanship, marketing and media manipulation to win the legislative wilderness battle.

A prominently displayed quote by Michael Carroll, now of The Wilderness Society, established the tone and direction of all that would come later:

“Car companies and makers of sports drinks use wilderness to sell their products. We have to market wilderness as a product people want to have.”

Though the mentoring conference occurred two decades ago, I only became aware of it in 2013. Nor did I know that my Utah friends had participated in it. Nor did I know that SUWA’s executive director was one of its mentors. This is the moment where my friends in the wilderness movement in Utah took a sudden turn in a direction I had not even remotely imagined possible.

These were all quotes from the report:

“Gimmicks…Catchy slogans…ask a rancher to support you…get Joe movie star as a spokesman…Cleverly quote John Muir…Ask experts to endorse your ‘product.’…Show people having fun in the wilderness.”

It all came to pass.

In the last few years, many of us have lamented the commodification and “dumbing-down” of wilderness. What better example than Moab’s latest incarnation as the overhyped “Adventure Capital of the World,” home of swing lines and zip lines and slack lines and every adrenalin-fueled recreational experience imaginable. I can only assume the Mentors must be proud of their success.

But what this conference created and what their report revealed was that, not only did the mentor gathering give its collective blessing to an all-out Disneyfication of Wilderness, its embrace of the strategies set forth in 1998 established the Disneyfication of the wilderness PROCESS as well. This is where the heart and soul of the wilderness movement died.

* * *

Come back to 2018. Consider the collision and consequence of those past changes and transformations —the disconnect between young people and the intrinsic aspects of nature, the planned efforts by government agencies and NGOs alike to pander to those changes, and the environmental movement’s efforts to quantify wilderness by assessing its economic value, while abandoning the aspects of it that mattered most.

Imagine the power and influence of these forces as they “created partnerships with outdoor recreation outfitters, suppliers, clothing manufacturers, etc., who already know a great deal about our federal land visitors and have a strong handle on how people are using that land.”

Imagine that in these past two decades, the real meaning of wilderness—solitude, peace and tranquility, open space—has disappeared from the wilderness debate. And understand that instead, the emphasis has shifted away from preservation of the natural world to the exploitation of its very beauty for fun and profit.

Consequently, the discussion and debate about “Industrial Strength Recreation” that the Grand Canyon Trust once believed held “more potential to disrupt natural processes on a broad scale than just about anything else,” abruptly stopped. Environmentalists quit talking about tourism impacts (“Never bite the hand that feeds you.”) The media essentially failed to address the issue as well.

Twenty years passed. Think about it. If you’re 35 years old or less, you may have never heard any discussion or debate about the tourism/recreation industry or its impact on the land and the small communities of the rural west. Hardly a word anywhere (unless you read this publication).

Anyone under 35…these are the young men and women now stepping into leadership roles in environmental organizations across the country. And yet, not only have they not debated the relative impacts of an Industrial Recreation economy, they don’t even realize there was ever a debate about the issue to begin with.

Now, the idea of enjoying wilderness simply for its contemplative value has even drawn the scorn of new environmentalists. Several years ago, when legendary rock climber Dean Potter boasted and promoted what he called the “first ascent of Delicate Arch,” I wrote an editorial critical of Potter’s illegal stunt. Support for my view was split along generational lines.

One young reader wrote, “Dean Potter has raised more awareness about nature and done more for the protection of our wildlife areas than an army of you idiots bitching on the internet will ever do. It’s this geriatric community of do-nothings that wants to sit by and look at rock that is getting butt hurt. It’s so sad, watching you people grow old and bitter, wanting the government to regulate everyone’s lives to suit your tastes.”

(Dean Potter died in 2015 during a ‘wingsuit’ jump at Yosemite NP)

Even congressionally-approved and designated wilderness itself is changing dramatically, with less chagrin or objection from hikers than one might expect. A study by Troy Hall and David Cole called, “Perceptions, and Behaviors of Recreation Users: Displacement and Coping in Wilderness,” attempted to determine if accelerated use of wilderness areas was degrading the “wilderness experience” of its users. Their conclusions, based on many interviews and research, surprised even them. They concluded:

“Most visitors perceive adverse changes, such as increased crowding and impact. Majorities reported that these places feel less like wilderness than they did in the past. (But) Most visitors have learned to cope with these adverse changes either by making simple adjustments in their behavior or the way that they think about these places. Consequently, most visitors report that their experiences are largely unchanged and that they are as satisfied with their experiences as ever… few people are absolutely displaced.”

In other words, while backpackers and hikers might have preferred more solitude, it was no longer a make-or-break issue. The one proposal that brought stiff resistance was restricting access to reduce numbers. Nobody wanted that.

A story by Heather Hansen at ‘High Country News’ reported that, “Another recent study based on users of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington and Oregon’s Three Sisters Wilderness, looked at what factors most detracted from visitors’ having a ‘real wilderness experience.’ It revealed that while people don’t like to have others camp nearby them in the wilderness, or when strangers walk through their camp, the biggest factor detracting from their experience was seeing litter.”

And to what lengths will they go to find solitude, or avoid it? When I need to know what’s ‘trending’ these days, I look no further than the crass commercialism of a television ad. Recently, via that medium, I discovered something revealing in the way we seek and appreciate solitude and our moderating efforts to escape technology.

It was a Verizon commercial that caught my eye; a young family was about to embark on a camping trip and the narrator asked, “Would you be willing to give up sharing your moment?”

Even before the 30 second spot ended, I was reminded of another tv ad, from 2011…just seven years ago. It was a Chevy commercial and four young guys, out in the middle of nowhere, kept stopping to check their cell phone signal. One fellow would jump from the Silverado, hold the phone in the air and shake his head. They drove further, stopped again. Still no success. Finally, up in the Ponderosas somewhere, he climbs atop a boulder, tilts the phone in all directions and smiles.

“Got it,” he grins. “No signal.” His buddies give it a thumbs up. Perfect. They’d found their camp site.

Jump back to the present and the Verizon ad. As night descends upon the happy campers, the family crawls inside their tent, hooks up their devices to the 4G network and settles in to watch a video of ‘Star Wars.’ The children look delighted. The parents beam.The narrator asks, “If you’re not on the nation’s largest and most reliable network, what are you giving up?”

What are they giving up? The very last scene depicts the artificial glow of the family tent, pitched beneath the dark silhouette of a majestic pine forest. Above the canopy, a brilliant star-filled sky shines brightly…and unnoticed.

This is the pursuit of Nature in 2018. This is what it’s becoming. This is what our lives are becoming. We cannot stand to be ‘dis-connected.’ The mere thought of it terrifies most of us. If the silence and solitude of Nature and wilderness are no longer qualities we long for, then what exactly is it we’re trying to save?

* * *

Watching all these changes, I assumed for years that this disturbing disconnect between a new generation of Americans and the natural world would lead to a diminished interest in environmental causes and even less participation. To a certain extent, I was right. Knowledgeable discussion over environmental concerns has all but vanished.

But I had not anticipated the rise of social media or its devastating effect on intelligent debate. A generation unaccustomed to, and even intimidated by, the most essential aspect of Nature–its untamed wildness–took comfort in an organized and structured approach to environmentalism and to Nature itself.

New found opinions and beliefs, strongly held to be sure, and passionate defenses of “causes,” often based on simplistic memes and well-orchestrated sound bites, now dominate the environmental field of play. Recently, when the recreation industry giant Patagonia spent millions to run online ads and tv commercials across the country that simply said:

“President Trump Stole Your Land…”

…there was no debate, no examination of the facts, no serious scrutiny of the massive corporation’s possible motive. Millions and millions of Americans simply said, ‘Ok…it must be true,’ and formed opinions to align with the ad’s message.

And who helped to create and even exploit this disconnect, not just from nature, but from the honest and intelligent search for the truth?

My fellow Baby Boomers; while a lot of us are frustrated by the changes we see, that group of Boomers who embraced tourism in the 90s bear the greatest responsibility for this entirely new kind of “environmentalism.”

Today’s environmental leaders are mostly from the post-WWII generation–the same self-proclaimed idealists of long ago. The hierarchy of the “New Environmental Movement” is composed of lawyers and advertising executives and investment brokers and venture capitalists and real estate developers and banker/financiers.

They have little interest in how their embrace of industrial tourism and recreation will gentrify local communities and damage the landscapes they claim to want to protect. They like the changes. And the “mainstream environmental community” that turns to these “enviropreneurial” leaders for advice and direction is firstly, and primarily, composed of older affluent progressives who have made Western land issues their “cause.” Many have transplanted themselves to the New West; others express their views from a thousand miles away. Regardless, few are armed with the history or context of the issues they are suddenly embracing or protesting.

These are the mentors to the younger generation, who are mostly drawn to wilderness country like southeast Utah for the recreational opportunities–climbing, base jumping, mountain biking and selfie-taking. This generation has never even heard the impacts of “Industrial Strength Recreation” discussed in any way other than positively.

And almost ALL of them place the economic value of wilderness protection at the very top of their priority list, along with the quality of their own recreational experiences.

* * *

What does the future hold and what do those who hope to shape the future want from it? As energy costs rise and the population swells, what kind kind of tourism will survive? Many believe it will flourish and grow, but their vision requires it will be very different. Mass transit systems, shuttles–now touted as the ultimate “solution”— and a group ethic will prevail.

A certain amount of regimentation will be inevitable for mass transit and regional shuttles to operate on such a vast scale. In this future, opportunities for solitude survive, but not as some of us still define the word. Painful to ponder, but as inevitable as sunrise.

What’s notable is that for many travelers to Moab in 2018, the Future is already here. And for them, it doesn’t sound that bad.

The world keeps turning over, again and again, faster than any of us dreamed possible. As technology continues to shrink the world, its newer citizens embrace the collective over the solitary. Solitude feels like isolation for many in 2018 and it has no place in the Brave New West. We all cherish the shared experience, but there was always a need for the empty room. Now the need recedes. “Rugged Individualism” has been in decline for decades. Now it’s in its death throes.

And so, we offer a lament, as the love and longing for the quiet moment, passed along from generation to generation, for more than a century, from Thoreau to Muir to Leopold to Abbey, draws to a close. The solitude is there, if you know where to look for it, but who’s looking? And who would notice or care if it went away?

Is that a bad thing? Who knows? Maybe not. But Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, “Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.”

The world has lost patience with Nature these days. They’ll never know what they threw away.

* * *

“For those who go there now, smooth, comfortable, quick and easy, sliding through as slick as grease, will never be able to see what we saw. They will never feel what we felt. They will never know what we knew, or understand what we cannot forget.”

Edward Abbey

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

The death of Solitude is the death of Wilderness.

The greatest failure of the environmental movement is the complete avoidance of the one greatest threat to the environment. Well, some tried:

“You don’t have a conservation policy unless you have a population policy.” ~David Brower

My inherent A.D.D. kicked in long before article’s end, but seeking (and finding) solitude in Nature is nowhere near as difficult as it would otherwise appear, even today. Simply avoid roads, trails, parks (national, state or county) and trailheads. Maybe use these means to get closer to the backcountry—I go by thumb—but then travel afoot, with enough supplies to say goodbye to the hordes for a week or two. Most citified folk cannot manage more than half a day’s hike, and prefer not to, for fear they won’t find any coffee shops or burger joints.

I know that each time I do this, about ten times a year, I have yet to see another soul, even in Canyon Country, where foot travel is generally less confining than it would be through thick forests. When I do meet another someone, it’s always an individual I can relate to, someone—dare I say?—I even enjoy meeting. There’s still a lot of empty, unpackaged land in which to get lost.

Humans are herd animals, dependent not just on one another, but on wheels and petrol. It is a problem where roads and entry stations exist, no question, but it *is* entirely avoidable.

Amen,Jim. We waited in that line at Zion Canyon just last week… I talked with a fellow who had tried to hike Angel’s Landing and he said there were so many people on the trail, that they were in such a rush to “bag” the Landing, that they were so rude, he turned back. He was literally afraid that somebody would inadvertently nudge him off the narrow one-lane section of trail and find himself plummeting a thousand feet to his death. What a wonderful place to take a hike, eh? I’m told the view is incredible. Oh well. We found solitude at Zion, but not on any trail, that’s for sure.

I don’t disagree with the sentiment, Jim, but man, you could use an editor to tighten up your columns.

Jim, as the above referenced “avid mountain biker” (who’s a dedicated conversationist/environmentalist and volunteer public lands steward), I do think that too many people impacting an area is a problem. The point of my original comment (that was partially quoted and taken from a comment I made on The Canyon Country Zephyr Facebook page, was to ask the The Canyon Country Zephyr for their proposed solutions. See the original link where Canyon Country Zephyr/Jim Stiles stated “…I don’t see any solutions.”

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/posts/1892171380807547?comment_id=1892225707468781&comment_tracking=%7B%22tn%22%3A%22R4%22%7D

Here’s the full context of the conversation between Jim and I from the link:

Me: “Ugh, people who want to experience the awesome protected public lands and wonderful stunning beauty of Arches National Park are THE WORST, right everyone?

But seriously, The Canyon Country Zephyr, can you provide a link to your commentary article outlining what problem you are specifically trying to point out in these Moab traffic photo posts, and present your proposed solutions? I know you’ve written extensively about how crowded Moab is and how it was somehow nostalgically perfect in some previous past time (your exact date in the past when you claim Moab was at its best would be helpful), but people who want to experience our wonderful outdoor places should be encouraged, not shamed. Experiencing nature is great for everyone, right? We all agree that proper management of our public lands is needed to protect the lands, but as a news source who has intimate knowledge of the area, its people (both residents and visitors), and places, I’d like to know your specific proposed solutions to what you are saying the problem is. Thanks.”

–

Response from The Canyon Country Zephyr: ‘”Seriously,” Mr. Hackett. We are simply documenting the state of industrial strength tourism in the Spring of 2018. This is the ‘real world,” and I don’t see any solutions. Recent NPS proposals to raise entry fees to seventy dollars were unfair and discriminated against those with more modest incomes and the idea was scrapped. A reservation system would be a bureaucratic nightmare of unprecedented proportions. The idea of creating more entrances at Arches, creating loop roads and diluting the traffic would ultimately fail–“goldfish grow to the size of the bowl.” More access would mean more people….More than anything, we post these images to point out that in this day and age and culture, there are obviously thousands and thousands of people like yourself who are NOT bothered by the crowds if it means you can get in there for a couple hours, take a few photos and post them on facebook….I worked there for over a decade and I thought the park was overcrowded when annual visitation topped 400,000—today it approaches 2 million…..so, like I said, I post these pictures just to let people see for themselves what’s happening and what effect massive marketing and promotion (coupled with relatively cheap gas) can have on national parks. So enjoy!”

–

My reply: “Thanks for your reply, Jim, I do appreciate your thoughts. I respect your opinion as someone who knows more about the history of Moab/Arches/Utah than most anyone. I’m just trying to look for solutions.

While marketing and promotion and social media and cheap gas and an improved economy have all contributed to more people coming to Utah’s natural areas, the simple fact that there are just more people in the world is the biggest issue. Of course, as older residents, you and I (and old Ed, who wrote the book that was the main reason I wanted to first visit Utah/Arches) had the luxury of visiting Arches when it wasn’t as busy. Are we to shame those who were born recently and come to visit today, and blame tourism as the evil cause? I try not to, and instead try to look for policy that allows us to share our public lands in a sustainable manner without simply locking the gate and calling it a management policy.

Most people don’t enjoy crowds, but at what point is a place “crowded?” For Arches, it sounds like it became too crowded the day the paved entrance opened. Or was it when Nixon signed the bill changing it from a National Monument to a National Park? Moab became too crowded when the uranium boom took off. Or was is when the Interstate Highway System came to Utah? Or was it when tourism started picking about after the uranium boom went bust?

As Federal public lands policy seems to more lately be reducing access to lands (due to budget issues), I’m concerned that the remaining access points will simply get more and more “crowded.”

Some solutions I see includes much of what Abbey wrote many years ago in “Polemic: Industrial Tourism and the National Parks.”

My personal solution is to ride my bicycle to visit our beautiful public lands, and to go to “crowded” places when they aren’t as busy, and encourage my friends and family to do the same. But as more people want to experience nature, I want to work toward encouraging that in a responsible manner. People keep making more people, and that requires solutions.

Thanks for listening, and keep up the good words.

And here’s a link to the Arches National Park Traffic Congestion Management Plan (TCMP) webpage for those interested: https://www.nps.gov/arch/getinvolved/tcmp.htm”

And once again, keep up the good work Jim!

Here’s the first step in any solution to the overcrowding of southern Utah–scrap that “Mighty Five” crap immediately. Utah’s public lands don’t need promotion. The world already knows about them.

Agreed!

As an “astro-landscape” photographer, my passion could not be more hyped up and popular as of late. It seems that Instagram, Facebook, Flickr, literally all of social media is full of “me too!” photos of trophy spots that are hunted down and bagged like an exotic safari animal.

I find myself struggling to figure out ways to share my photos with the world and have them positively affect the situation, instead of the opposite. I’m not really sure what to do, but I’m starting by never letting my “content” hit social media without real, honest truths in the captions and stories etc. about what the crowding may be like, and how delicate the location may be.

And I still find myself spending a lot of time seeking out the more remote places, well off the beaten path, where only the truly curious folks bother to venture.

Sure, I won’t stumble across a whole new “Delicate Arch” in the middle of nowhere, and have a totally new, unique photo that nobody has ever gotten before. Heck, I might come back from a trip with nothing but boring photos of featureless wilderness, or “just another random canyon”. But I don’t care. I’m just waiting for instructions or ideas on how to actually affect change to the situation, whether by voting or voicing my feelings in other ways, so that these beautiful places can be preserved for future generations to enjoy, instead of being “celebrated to death”…

US population 1970 = 203,392,031

1990 = 248,709,873

2010 = 308,745,538

More people equals more traffic. A rapidly increasing population is a threat to all the planet’s resources.

Although I do think you make a very interesting point about how the wilderness is marketed.

Traffic: Your webcam photos both sensationalize the issue and point to a separate problem. As I type this (around 2:30 PM MDT on a Friday), the entrance station webcam show eleven (11) vehicles, two of which are tour buses. The wait time is probably less than ten minutes. The UDOT camera at the Hwy 191 entrance show no cars. I have no sympathy for persons who don’t take advantage of the information freely available on the internet and plan ahead. I’ve managed to travel to Zion half a dozen times in the past five years – spending nearly ten total weeks of time – and the longest I think I’ve waited for a shuttle is 15 minutes (from Temple of Sinawava in the evening).

The fact that Moab and Arches haven’t worked out a shuttle system in more than a decade of study (much to Abbey’s dismay, I’m sure) is the fault of the locals more than the visitors. Would a shuttle system lead to the visitor boom that Zion has seen? Perhaps, but it might just as easily ease the current congestion.

I’ve been “at it” for decades, and Styles been around for a good while too; and each of the posters on this site with their own unique experience, insight (prejudice, false memory, bias) and direction see the “problems and solutions” in a most ubiquitous manner; many just complain though and never speak of alternatives solutions – adaptation to changing circumstances. The user groups, human powered, machines; the advertising, promotion, social media and word of mouth. And so many of the groups in the Moab region, completely different tribes that don’t blend and are often hostile like rabid deity crowds. Auto drivers and casual walkers and sight-seers, climbers, canyoneers, bikers, river runners, ATV/UTV, Jeep/4WD. All groups to varying degrees impact the economic multiplier of the Moab area, and as long as the motels, restaurants, grocery stores, housing rentals and other “mechanical bike/vehicle rental” operations are busy, they simply wish to expand the season and gain more bounty. Amazing that no Republican Senator or House member has stepped up and sought funding for shuttle systems (that could be tried) in the Moab and Arches areas. And the Utah Travel Council continues to “thunder” promotion of the states national parks. Was in Zion last week – currently (new) parking meters along the full course of the highway leading to Zion, and meters on side streets (like adjacent to Zion Adventure Company where we use to park at 6am for a shuttle ride to the E side). Forced us – being gone the full day – to try something different. Personally I can mostly find solitude in any national park in this state & in regions of the Swell, Book Cliffs, Escalante/Boulder, Basin & Range. Glen Canyon (rims & side cyns) Maze and back side of Needles still offer much solace and natural wonder. And how much BLM country in whatever region is not also a place of frequent quiet. Pound the drums folk re the conflagration of vehicles, crowds and disaffected society that wander like “sheep” following routes that others lead. Or in a quiet and meaningful way, step up and offer solutions re the crowds, resource protection, ecosystems, wildlife (and your special god given user group); or cast your lot with the AYL Chad Booth crowd, Blue Coalition and Romney, who want all FS and BLM lands turned over to the state; all WSA’s re-branded as multiple use zones and the antiquities act (Monuments and Parks – essentially) banned. There are many religious out there, with many proudly shouting loud fire and brimstone missionary cries. Be interesting to channel the likes of David Brower, Stegner, Abbey, and all those having a hand in creating (monuments/parks) in Arches, Canyonlands, Hovenweep, Natural Bridges. Would they put their hands up in disgust or move out and begin the path of dealing with the present situations and in planning for the future? (Abbey might wander off, but the others I imagine would pour in bounds of creativity.)

There is no solution to the over crowded National Parks on the Colorado Plateau as long as the philosophy of St. George, Moab, Phoenix, Las Vegas, Durango, Flagstaff, Santa Fe, indeed the entire Colorado Plateau is, to paraphrase Ed Abbey, the philosophy of the cancer cell which is unlimited growth. Not to mention the marketing of these places to lure in more of America’s burgeoning population and their dollars to “enjoy” the “adventure” to be had in National Parks and their adjacent lands as long as you don’t mind the crowds.

For me the new reality is that the function of these places is to keep the tourists and “adventurers” out of my way and out of my favorite wilderness, canyons, rivers, mountains, and other places which provide solitude and where I can camp, hike, explore and recreate/re-create in what now seems to be an anachronistic pastime. Those places are out there but in the world of population increase, GPS, bagging places and experiences, and posting it all, along with the requisite selfie, who knows for how long? I am not optimistic.

Thanks, Stiles, for the history and continuing documentation of what’s going on in the “new west”. Your book, “Brave New West: Morphing Moab at the Speed of Greed”, was sadly prophetic and that prophecy is sadly almost fulfilled.

Right on, Jim. And, the Travel Council is asking UDOT for $250,000 to increase advertising Moab in the San Diego and LA areas! The vote was unanimous. They have all “drank the Koolaid” that endless growth is good. Fuck them!

I think that what is happening here is that a de facto Arches National Park Sacrifice Area is being established. Maybe it’s just as well to have a mile long line of “those people” parked out on 191 as to have a mile long line waiting for their turn to drive down the Shafer Trail.

To add fuel to Jim’s fire, if you would like to see a version of hell on earth do a google image search for “spring break beaches” and surf around. Since you are the type of person to be reading these comments, I have no need to add additional commentary to the photos.

Jim,

I enjoyed this piece. I am learning to find the quiet places as I work on my bucket list. After 50 years of looking at it, I submitted Mt. Tukuhnikivatz on Monday. Had the entire place to my self – and 10 mountain goats and their kids. Saw black bear and two cubs Thursday near Winter Park. Angels Landing at dawn. Life is good!

Keep it up.

Poor Jim, I know exactly whereof you speak with the multitudes crowding into this formerly open country like hordes of Visigoths descending upon the peaceful valleys of the Po.

Uninterested in peace, solitude or, gods forbid, introspection, they come armed with Spotify, wireless speakers and micro kegs to party at remote hot springs, or to take shots of themselves flashing their titties at the scenery for Facebook/Instagram/Twitter/SnapChat.

In my saner moments, I give deep contemplation to the choke points and the processes that might be used to sever them in order to stem the westward tide through my beloved Shining Mountains. The thoughts pass over me like the cool waters of a mountain stream until I’m jarred awake from this pleasant daydream by the screaming of a private jet dropping into Aspen or Eagle, and the thought they would just squeeze through the cracks, or worse, beam in wirelessly.

I do not despair. There is the Trumpian economic “plan,” which will soon find us in a free fall that will make 2009 look like a Sunday afternoon barbecue. There is also that great limiter, water, though I fear the lycra-clad lifestyle refugees who are constantly marketed to by our Chambers of Commerce would rather drain every stream in the high country than do without a single convenience.

There is yet hope- the Yellowstone Super Volcano has been very active of late and is apparently overdue for spectacular release.

A home run.

As a ranger in Glen Canyon NRA in the 70s I tried to tell people to just go explore, Maybe go see where Everett Ruess vanished , but you have to find it yourself, I wont tell you. And if you dont so what, you’ll still experience something. Not now. Now its in Outside Magazine or Mens Journal with maps and braggado . I think there is another phrase for this stuff…the Commercialization of the Ego.

The problem as Mr. Brower and another said is population growth in the U.S but also international access that did not exist even 30 years ago. We live not far from the South Rim, when visitors come the Grand Canyon is of course something they want to see. I’m not a xenophobe but the world is better represented there than the United Nations. We operate a Facebook page about ruins and rock art in the southwest. Out of curiosity I looked through the membership for country of origin. Over 25 countries represented in the first 3-400 members, 6 of the 7 continents, still waiting for Antarctica. Maybe they saw a travel brochure but more than likely they saw a PBS BBC or some other production.

The bliss and solitude that was Arches for Edward Abbey reflected the place and time of the world circa 1956-57. A world population of 2.8 billion. Now it is 7.8 billion. Plus there is a lot more wealth out there, along with jet airplanes and fast air conditioned cars and camper vans. Everybody itching to travel a LOT more than in 1956.

When I first came to Moab, from Oregon, I was a college student with a well-read paperback copy of Desert Solitaire in my backpack. We drove my 1969 VW Squareback – a challenging 3-day trip from Eugene. An adventure! Somehow our mode of travel resonated with our destination: funky air-cooled no pretense. Yeah, that was my car alright. And that was my impression of Moab back then. I remember seeing a lot of cars like mine in Moab at the time.

I reprised that trip in 2003 in another squareback, this one a 1971 model. I didn’t see one other air-cooled VW there. Now even bearded college students coming to Moab were driving air conditioned Outbacks. They regarded me in my VW with mild disdain and wonder: dude, how can you drive a car without A/C???

And now the hordes are even wealthier and more numerous. And everybody has A/C.

The adventure is long long gone I’m afraid.

I understand the “perverse satisfaction” you enjoy when reviewing traffic on the Moab Autobahn into Arches. You have warned the environmental community, local policy makers, and southern Utahites for decades about what woes Industrial Tourism would bring to the area. I grew up in Moab and now live in an undisclosed location nearby which has unfortunately caught the eye of urban real estate investors with plans to turn meadows, forests and grazing lands into vacation rentals and second homes for wealthy urbanites charmed by the beauty and “quaintness” of local culture. No perverse satisfaction here, rather I experience horror at the commodification and breaking of the land. For a hundred years, Moab was little more than a desert outpost because that’s what the available resources dictated. Those resources; water, agricultural land, grazing land, forests, aquifers, rivers, lakes and streams are being stressed into extinction. The desert cannot be forced to support urban populations. “New West” is an innocuous euphemism for the death of the rural West way of life and the lands that have sustained it for a century.