(Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in the Oct/Nov 1999 Issue of the Zephyr. Kent Frost lived until May 16, 2013. To read his obituary from the San Juan Record, follow this link: Kent Frost May 16, 2013.)

Celebrated river runner and artist Dick Spragg termed it “canyonitis”–the tendency of experienced red-rock explorers to protect their discoveries from later wanderers who follow in the paths they blazed.

As Sprang explained the affliction in 1984, its symptoms include “a sense of proprietorship that is developed through much experience in that area and which sense of…ownership intensifies as newcomers appear with tales of their limited activities in the area, their supposed discoveries and new finds that are an old story to one who has been active in that country for many years…It results from his intense identification with isolated country where the sense of country dominates all activities, where his stature is cut down to size by the immensity of the environment and which diminution is compensated by a sense of self-worth that grows in him as he survives the country, explores it, and comes to love it.”

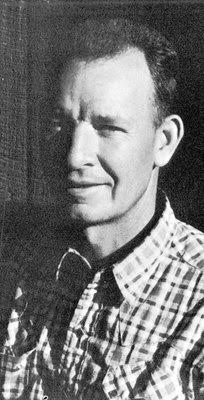

Many, if not all, of the canyon country’s most influential Euro-American explorers of the 20th century have been afflicted to a lesser or greater extent by “canyonitis” (also known as “firstitis”). My admittedly unscientific tally includes the following inductees: Explorer John Wesley Powell. Writer/Photographer Ward J. Roylance. Riverman Arthur Chaffin. Indian trader/guide “Hosteen John” Wetherill. Edward Abbey. Norm Nevills. Desert magazine publisher Randall Henderson. Everett Ruess. Even Sprang himself. And what about women? Katie Lee and her late nemesis Georgie White shouldn’t be neglected (Katie would certainly never let us forget it if we did.) And, provisionally, we can include Kent Frost, the 82-year-old river runner and trailblazing backcountry guide. “Provisionally,” because Frost is so generous, so eager to share his knowledge and so loathe to vocalize his own praises, that it would be easy to underestimate his accomplishments.

“Outside the river community, Kent’s not much well-known,” agrees Colorado and Green River historian Roy Webb, an archivist at the U. of U.’s Marriott Library, where Frost’s journals are archived. “Maybe that’s because he’s quiet and unassuming” and doesn’t attract headlines, unlike some of his better-known peers. “In a quiet way, though, he’s introduced a lot of people to the country—through guiding and his book. And a nicer guy you couldn’t want to meet.”

Born in 1917 in Arizona, Frost spent his childhood traveling between different locations in southeastern Utah as he followed his father’s enterprises. These included at various times an alfalfa farm in Monticello, a ranch on the LaSal Mountains, traplines in Monument Valley and on Navajo Mountain, and a sawmill on Blue Mountain. Yet such job-hopping wasn’t out of the ordinary, as Frost reflected in his memoir, My Canyonlands. “The demands of life here are harsh. People earn their living in odd ways. Ingenuity still counts. Most folks find is necessary to do three things at once for an income—they run a farm, ranch, or store, hold a civic office, then find a third job for cash. Not moonlighting so much as trilighting.”

Not surprisingly, all the moving around interrupted Frost’s formal education to an extent he found difficult to overcome. But there were other advantages. He got to see a lot of countryside, much of it still wild and relatively unexplored. On horseback, in a series of automobiles and—to an extent we would find surprising today—on foot, he wandered in ever-widening circles from his home base on the family’s alfalfa farm at Dodge, ten miles outside Monticello. During winter, a time when he was free from his obligations on the farm, Frost roamed extensively through the unpopulated sandstone spires of the aptly-named Needles district in what would later become Canyonlands National Park, discovering stone arches and old cowboy camps, poking his head into centuries-old ruins left behind by Ancestral Puebloans, and occasionally coming upon a rancher or trapper in the vast emptiness. Traveling light, he usually carried only rice and raisins and relied on his .38 special revolver to pot rabbits for supper. Even in the very coldest weather, he eschewed a sleeping bag, relying on the heat from his campfire.

During this same era, Frost also trekked up and down through Grand Gulch, returning regularly to this no-crowded but then lightly-visited region. “In all my hikes,” he wrote in My Canyonlands, “I have never found two canyons alike. Each has its own colors, its special erosional features, its own personality. Grand Gulch is a royal canyon of great beauty. Passage down it is easy. It has many springs, superbly beautiful walls, and decorative rimrock that can be admired from the canyon floor. It runs a gamut of different moods for sixty miles—from its head all the way to the San Juan River. There it drops off rapidly in huge waterfalls. Great boulders lie in the water course, and gigantic piles of driftwood line the sides. The final plunge of fifty feet sends the water leaping to the San Juan.”

But such a place held too much appeal to the outside world for it to remain undiscovered for long. Frost may have “had the freedom of it” (as he wrote in his book) for a time, but even then, one suspects, he was aware that the country was bound to change. It wasn’t for nothing that he titled the final section of his book “The Dwindling Wilderness.”

“The biggest change is in roads,” Frost reflects in his usual soft, thoughtful tones. “Before the uranium boom, there were few roads and it was hard to get around. You’d take a stock trail from one area to another. Natural Bridges was the end of my world one way, Mexican Hat on the other and Dugout Ranch on the other.”

If, as Frost says, Monticello and the Chesler Park country were a “big world” for him when he was a boy, by the time he was a teenager wanderlust had begun to pull him beyond the familiar horizons and landmarks. “I went on my first river trip with Norm Nevills in 1938,” he says. “That’s when my world really started expanding.” Already, he had spent two years driving a truck across Monument Valley as he delivered flour from his family’s mill. “John Wetherill had the trading post at Kayenta then and he rented out a few cabins. On one of my trips through, the cabins were all full so he had me sleep on the counter. I liked that well enough, sleeping in his store. He was a great guy; everybody liked him.”

Because of his itinerant childhood (and also, one suspects, because he had his attention focused firmly on the horizon so much of the time,) Frost’s attendance in school was haphazard. But by the time he met riverman extraordinaire Norman Nevills and his wife, Doris, in the mid-1930s, Frost was eager to start making up for the deficiencies in his early education. “Norm loaned me river books like Major Powell’s first trip down the Grand Canyon. Then I got hold of a geology book with simple explanations of things related to the earth.”

Another significant influence was rancher and riverman Arthur Chaffin, who built the Hite Ferry on the Colorado River. In 1939, Frost and his cousin Ruell Randall decided to explore the country from the Blue Mountains to Hite. Upon reaching the mouth of White Canyon, they lashed together pieces of driftwood and decided to continue their trip by the water route. After a precarious ride of only a few miles, they pulled in at the Hite Ranch. Chaffin took one look at their rickety craft and told the pair he’d build a real boat for them if they performed some tasks around his ranch. The two spent a week chopping weeds and rehabilitating a dilapidated Model A Ford before Chaffin, good as his word, constructed their homely but workable craft. His wife, Phoebe, packed them a larder of watermelons and Guinea hen eggs and off they went. After a glorious week on the river, the pair beached at Lee’s Ferry, 160-plus miles downriver. Thoroughly tired of drinking the silty river water, they knocked on the door of the nearest house and begged a pitcher of debris-free ice water. They made their way back home by walking and hitch-hiking.

The trip marked the beginning of Frost’s love affair with Glen Canyon—a relationship that continued until the mid-1960s when the waters of Lake Powell began to back up behind Glen Canyon Dam. The reservoir inundated a place he describes as “the most beautiful site on earth.” “I was really sad about Lake Powell coming in,” he says. “It was a terrible decision to destroy all those canyons and all that history.” Today, he’s a vocal member of the Glen Canyon Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to draining Lake Powell and restoring the Colorado River ecosystem.

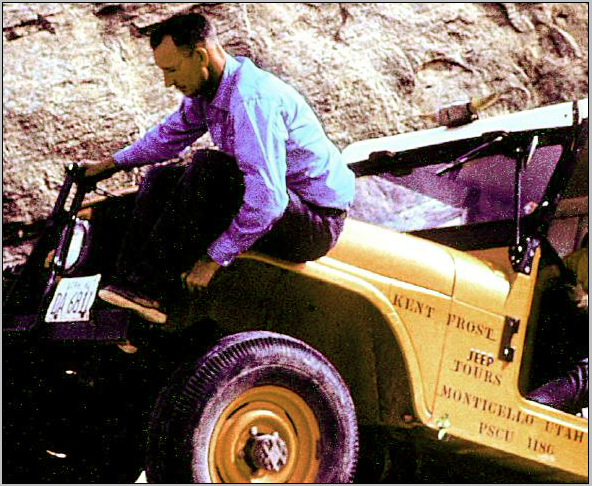

Unlike many of his peers, who never fully recovered from the devastation of losing their playground (and sanctuary) in Glen Canyon, Frost moved ahead. In 1953, he had rounded up two of the primitive Jeeps of the day and started a guide business, shuttling tourists around the country he had previously come to know so well on foot. By the mid-1960s he had his hands full accommodating the scores of adventurers who wanted to experience the country with the help of an expert guide. Although Frost later conceded that he didn’t get rich with this enterprise, he considered it the culmination of his experiences up to that point in his life. “Those were good times,” he says. “People were adventurous and didn’t make too many demands; we had meat the first night or two, after that it was lots of onions and potatoes and corn bread, but they didn’t complain.” During his years of guiding, Frost’s circle of acquaintances grew rapidly. He came to know personalities diverse as politicians Barry Goldwater and Calvin Rampton, author Wallace Stegner and photographer Philip W. Tompkins.

Stories about the friends he has made over the years come easily to him, and he is particularly eager to cite people who had a formative effect on his life. If the Nevills were responsible for sparking his lifelong interest in learning, Chaffin taught him to “recycle anything that was recyclable.” “Living way out there on the ranch like he did, he had to learn to make or adapt anything he needed,” Frost explains, holding up the sole of his boot to reveal it is soled with a horseshoe. His point is clear: never throw away anything that can be patched.

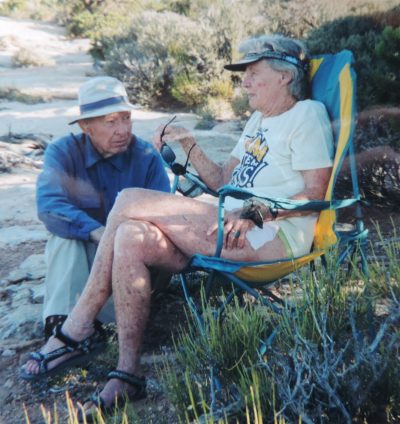

Frost evidently heeds that message in his personal life as well; he’s been married to his wife, Fern, for more than half his life. The pair met when he was 32 and she was just two years younger. After overcoming her father’s skepticism, they wed in 1949. “We just celebrated our fiftieth wedding anniversary this May, so I guess we did something right,” he says. “She was able to adapt to my way of life and I adapted to hers.”

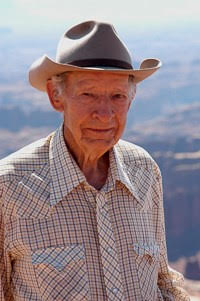

At 82, Frost spends his time “hunting projects.” He continues to work at his blacksmith forge, making tongs out of horseshoes, for instance, or forging tools from scrap iron. In addition, he remains a popular speaker at gatherings throughout southern Utah and western Colorado. The National Park Service recently recognized his stature when it christened its new high-powered river rescue and patrol jet boat the US NPS Frost. “That was something,” Frost marvels with characteristic humility. “I was at a loss for words when they told me.”

The little boy who once described the tiny village of Bluff as his “map of the world” has since gone far beyond those boundaries, but says he has lived a full life free of regrets. “It seems like I’ve kept floating along through life and that everything turned out all right. There was always a guiding influence I couldn’t explain. Regardless of the situation, I’ve seemed to get out of predicaments without special precautions.”

“I don’t know what the next trip will be,” he concludes. “But whenever somebody comes along with a plan to go out and do something, I’ll be ready.”

Barry Scholl lives in Salt Lake City.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Kent Frost was a frequent visitor at my home…he and my folks were kids together and the friendship lasted through the years. Bob and Eva Stocks had many such friends, but I think Kent Frost was one of the most consistent ones! Good memories….