I have had a soft spot for cowboys and the cinematic Western since I was old enough to walk and say, “giddy-up.” It is one of the great regrets of my life that I never became proficient on a horse. As a kid, I devotedly watched all my tv cowboy heroes on Saturday morning. I still do. When I played ‘cowboys’ out in my neighborhood, I even created my own soundtrack. Arriving home after a long day on the range, my dad would say, “‘Dum de de dum dum…dahhhh!’ has just rode in.”

It’s no wonder that now, all these years later, my favorite music is the score to “Lonesome Dove.” Running a close second is “Jeremiah Johnson, ” and that’s where Robert Redford enters this story.

Redford has starred in some brilliant contemporary Westerns over the past half century. He was the burnt out rodeo cowboy in “The Electric Horseman,” the gentle Montana rancher in “The Horse Whisperer” and the cynical, grumbling rancher in “An Unfinished Life.” He was the Sundance Kid in an earlier time, of course. And from a period a few decades before the post- Civil War cowpoke/bank robber, Jeremiah Johnson wanted to know, “Where is it I can find bear, beaver, bobcat and other critters worth cash money when skinned?”

But the American Cowboy no longer holds a hallowed place in the hearts of many Americans. In fact, cowboys are getting roped, branded, and blamed, especially by environmentalists, for just about every ill on the planet.

A while back I came across this essay in the Washington Post. While noting the criticism and its merits, the author, Blake Hurst, also came to their defense…

Once the hero of hundreds of movies, television shows and pulp novels, he’s no longer an icon. Instead, he’s a social pariah, spending his days caring for cows, the worst environmental villain that modern man can imagine.

No longer a larger-than-life figure like John Wayne or Gary Cooper, the present-day cowboy has the social cachet of an Exxon executive without the stock options or the private jet. He’s still out there on his horse or his four-wheeler, but he’s no longer anyone’s hero

… Cows make marginal land a source of nutrition, and that’s an amazing thing. The main indictment of the beef industry is that it isn’t sustainable, but surely a large part of sustainability is the cow’s ability to use what we cannot, benefiting us in the most delicious of ways….

Yet today we are told as often as a cow regurgitates her cud that the methane from millions of those miraculous rumens is an especially powerful cause of global warming. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, livestock accounts for around 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Is that too much? Not if you are hungry —

Local environmentalists have loathed the sight of a cow for decades; they hate the ranchers too. It’s hard to find much wiggle room in their heated opinions— it’s always been viewed from a very cut and dried, black and white perspective. They want them gone. And that means they advocate the cowboy/ranchers’ extinction as well.

Representatives of the Grand Canyon Trust, the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, and Durango-based Great Old Broads for Wilderness have long sought to dramatically reduce or eliminate public lands grazing in the interests of active range restoration.

Redford himself is hailed as Hollywood’s hero of the environmental movement. One blog that honors “celebrity activists” wrote that, “Robert Redford is one of the –if not the sole- pioneer in celebrity environmentalism.”

Redford, who has called Utah home for 40 years, is still remembered as the man who stopped the power plant on the Kaiparowits Plateau in 1975. “Without Redford,” the article explained, “the United States would have surrendered the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument to commercial hands. Redford’s advocacy kept the 1.7 million-acre out of the reach of farmers and developers until President Clinton closed the area from development in 1996.”

Out of the reach of farmers. And yet, Redford’s screen roles have always depicted a more nuanced, complicated, and even compassionate side to the very ranchers, farmers and cowboys that environmentalists love to loathe.

Redford played Sonny Steele, for the 1978 film “The Electric Horseman.” He’s an over-the-hill, whiskey swilling, womanizing, ex-rodeo star, reduced to selling breakfast cereal to pay the alimony. But he’s a decent and caring man, nonetheless, who steals a prize thoroughbred horse, in order to save it from its corporate owners.

I never met an environmentalist whose head didn’t explode over the mere mention of a rodeo, and of course, there are aspects of the sport that are troubling and wrong, for sure. But…Life is complicated. It’s what makes it interesting.

In the “Horse Whisperer,” Tom Booker is a rancher, somewhere in the Rocky Mountain West, who raises cattle, and no doubt uses public lands to graze them. He and his family eat a lot of beef and Tom saves horses from human abuse. Likewise, in “An Unfinished Life,” Redford is Einar Gilkyson, a bitter and guilt-ridden rancher, who still grieves for his dead son, also a rodeo cowboy.

Again, Einar is not the role model most environmentalists would seek to befriend. The Great Old Broads would hate him. The Grand Canyon Trust would want to put Gilkyson and Booker out of business. PETA would want Sonny Steele thrown in jail. Beyond condemning the ranching profession, shouldn’t they also ask what kind of men they are, or whether they are good to their families, or whether they pay their bills on time, or whether others might hold them in somewhat higher esteem. And why.

What lies in their hearts would be irrelevant. And that’s what’s missing in the conversation these days.

I had my own day of reckoning about 20 years ago. I’d begun to have apprehensions regarding the changing philosophies and strategies of my mainstream environmentalist allies. But I also felt conflicted about my alleged adversaries as well. I had never been able to muster the level of loathing for the “Old Westerners” that my compadres so readily displayed, and I’d even made efforts to express my personal admiration for them.And yet, my own words must have rung hollow as I otherwise did everything I could to condemn and marginalize their way of life.

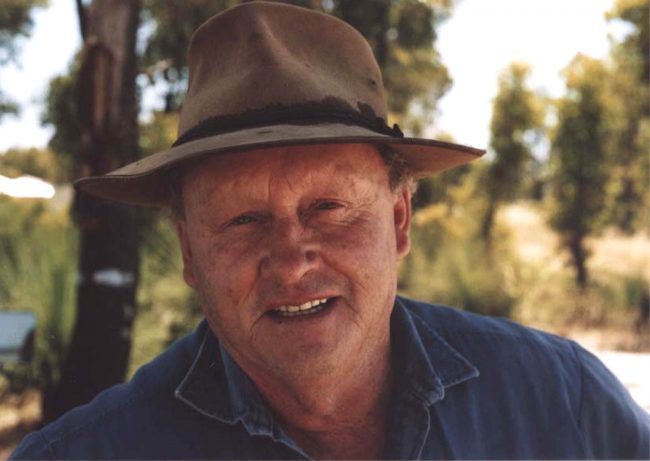

In 1998, this conflict presented itself to me directly in of all places, a remote stretch of highway in Western Australia.(WA) I was on a bus, traveling from Geraldton to Perth, when I struck up a conversation with the man next to me. His name was John Wringe and he was a cattle/sheep farmer from near the small community of Kirup in WA’s southwest. Castledene Farm had been a part of his family since 1862 and he was continuing the tradition, through good times and bad. It would mark the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

On that memorable bus ride, John and I talked non-stop for hours, shared our life stories, and pledged to meet again. We traded addresses, a year passed, and I returned to WA and to Castledene and the Wringe Family, who for years to come, would embrace me like one of their own.

John and I sometimes failed to see eye-to-eye, especially on some environmental issues. After all, his family had built their farm out of an old growth wilderness of eucalyptus more than a century before. He showed me ancient images of Castledene, from the late 1800s when carving a home out of the wilderness meant just that.

Even in the late 1990s, it was a hard life. The Wringes lived modestly on a home John had built in the 1960s. In 1998, they were still heating their water with wood-fire. The entire family worked dawn to dusk, rarely had time to just relax, and yet they always found time for me during my visits. They were my Australian family. (A decade later, John would be the Best Man at our wedding.)

One day, John asked me to compare ranching in Western Australia with ranching in the American West. I explained the public lands grazing debate and how most environmentalists hoped to shut down the practice altogether. In fact, the acrimony between agriculture and environmentalists had, even then, reached a fevered pitch.

John said, “So I guess if I were a rancher in your state of Utah, I’d be depending on those lands to survive? I mean, it sounds like there’s not enough private land in the West to really make a go of it without using those government lands…is that right”

I nodded. John paused a moment and asked, “So…would that make us enemies back in the States?”

It was hard to answer, but it was a seminal moment for me. “A moment of cleansing clarity.” I began to consider (finally) the Rural Westerners I had previously given little or no thought to at all. I took note of Wendell Berry’s admonition (repeated here yet again…)

“…this is what is wrong with the conservation movement. It has a clear conscience….To the conservation movement, it is only production that causes environmental degradation; the consumption that supports the production is rarely acknowledged to be at fault.”

* * *

I met Robert Redford once, in October 1975, in Hanksville, Utah of all places. I’ve told the story of my humiliating 30 second conversation with him before, so I’ll try not to repeat myself too badly here. But briefly, I came face-to-face with the great Redford in front of Jim n’ Elle’s Steak House and managed to tell him that “next to ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ ‘Jeremiah Johnson’ is my favorite movie.” Let’s just say my dog Muckluk fared much better than I did in Redford’s esteem and leave it at that.

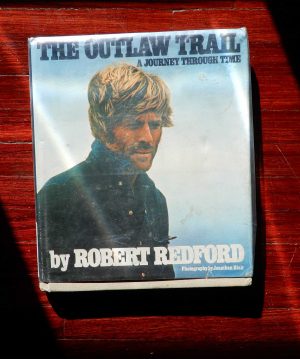

I only mention it here because later I learned why Redford was in Hanksville. He was writing a long article, and eventually a book, for National Geographic called “The Outlaw Trail: A Journey Through Time.” His connection to the topic via his portrayal of the Sundance Kid, and his interest in Utah made him a perfect author for the story. In the book’s preface he wrote, “The Outlaw Trail…is a geographical anchor in Western folklore. Whether real or imagined, it was a name that, for me, held a kind of magic, a freedom, a mystery….”

The publisher added, “Its is Robert Redford’s hope that the locations, legends, and heritage that inspired this book will be preserved.”

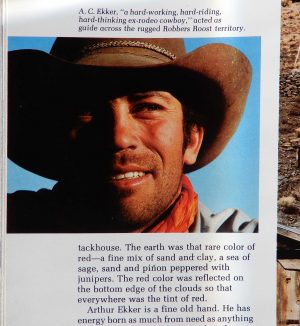

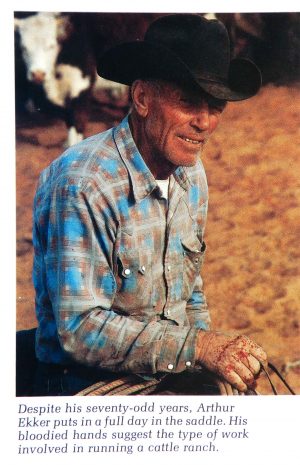

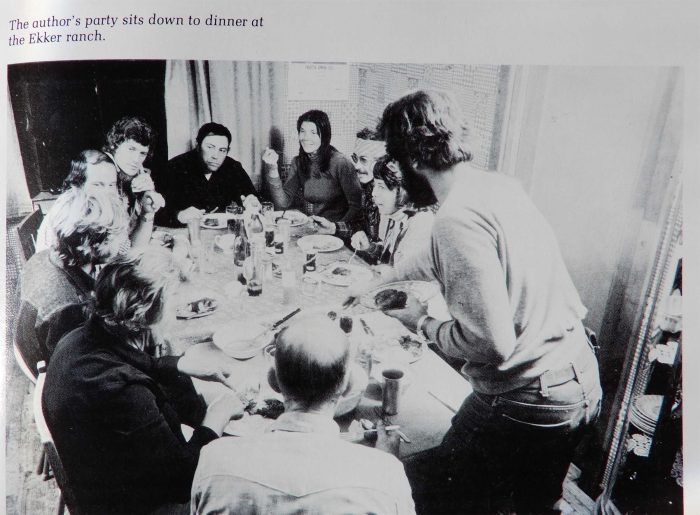

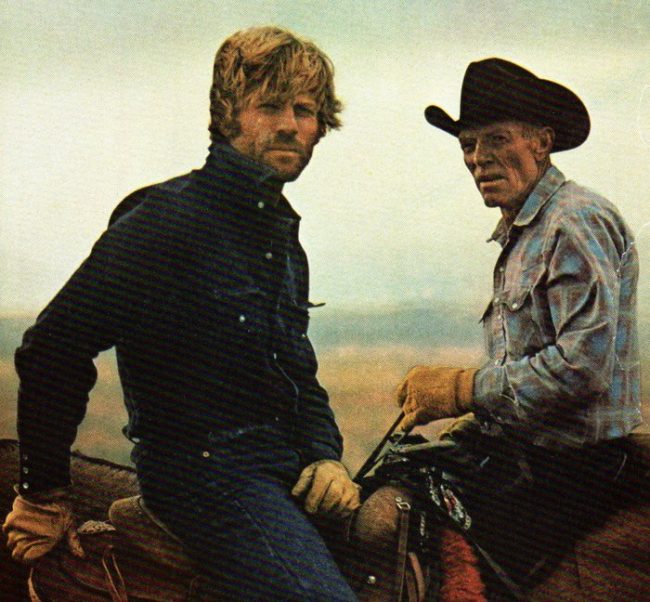

Among the legends and locations that Redford found along the trail, he took special interest in the life and times of Utah rancher Arthur Ekker, and his son, A.C. They were to take Redford and his party into the Robbers Roost country near the ranch where Arthur Ekker was born and where he’d spent his entire life. Redford noted that, “Arthur Ekker is a fine old hand. He has energy born as much from need as anything else, and at seventy-three, work and movement are ingrained in him.”

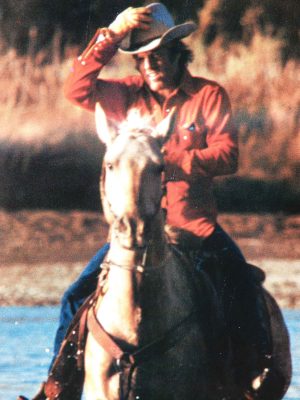

“A.C,” Redford observed, “is a hard-working, hard-riding, hard-thinking ex-rodeo cowboy who suggests, more than anyone I’ve come across, the verve, strength, enthusiam and enterprise attributed to the early settlers. In a sinking society of worn leather and tired spirits, he stands out as a leader—forward-looking, hopeful…”

During their long ride in search of wild mustangs, Redford asked questions. He asked Arthur about everything from cattle rustling to Butch Cassidy, to Brigham Young. Arthur talked about ranch life in this hard-fought and hard-to-hold country, and Ekker was as candid and plain-spoken as his weather-lined face was an open book to the life he’d led.

Redford wondered what Ekker’s views might be on federal land management and the BLM. Arthur explained, “Oh, I get along okay with the Bureau. They came along and cut the land up pretty good. Don’t feel it’s worth that much. Families used to have more land here. People fought a lot with ’em at first. But it’s okay now. Trouble is, they don’t listen to no one. Not me, not anyone.”

His tone was more resignation than bitterness. And he noted changes in the weather about 50 years before anybody else. He told Redford, “We’ve lived here two or three generations. We’ve seen the land dryin’ up. There used to be lots of antelope and wild horses and deer and cows and wild ducks and the like ya can’t find now. Used to put up two hundred and ten ton of hay in a season. Now you can’t get ten ton. Used to rain every other day or so in summer—a man could put up a good livin’–now there’s no water.”

Redford “mentioned that new technologies were being developed for growing crops and food in areas of the desert and perhaps such technologies could be applied to this area. Ekker looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, but that’d take a lot of money, wouldn’t it?’”

And finally, while Ekker looked like a man who couldn’t know more about the rest of the world than what he could see his from his ranch house porch, his grasp of international economics was impressive. Ekker explained, “Well, you see, the rancher today can’t compete with the beef they’re importin’ from Argentina and Venezuela. They raise lean beef there from smaller cows bred specially for the job, and that lean beef is what supplies most all the fast-food chains in this country. So imports are dominatin’ our trade and cuttin’ into our market. And with the current recession, feed prices are up so high and sale prices so low that we end up losin’. Because of Earl Butz [then Secretary of Agriculture] everything we do today is tied to foreign policy, so we’re busy scratchin’ everybody’s back abroad, and we’re out.”

Redford took note of Arthur’s honesty and candor and wrote, “I thought how refreshing someone like Ekker might be in Washington.” When Art Ekker died in 1978, Robert Redford came to Utah, to be at his funeral.

* * *

In 2020, Robert Redford would be hard pressed to find a single environmental ally who would share that kind of sentiment. Art Ekker in Washington? They’d ask incredulously. You might as well make Ammon Bundy the Secretary of Interior.

Art Ekker would be mocked and ridiculed by today’s environmental progressives. He’d be condemned not just for using public lands to help support his business, or for his grazing practices on them, or that using BLM lands makes him a “welfare rancher,” or that eating beef is a sin. He’d be condemned for contributing to the destruction of the entire planet because of his farting cows. Art Ekker would be a pariah.

Even in 1975, it’s certain that some of Redford’s personal, political, and environmental beliefs would have clashed with Ekker’s. But there’s a difference between then and now.

Whatever their diverging views might have been, Robert Redford saw the Ekker family in a broader and kinder and more understanding light. He admired Arthur’s candor and honesty. And paid tribute to the family’s dawn-to-dark work ethic. He respected their history and the future they sought for themselves and their loved ones, even if it wasn’t a pathway Redford could completely comprehend or want for himself. He didn’t hold them in contempt or revile their very reasons for living, just because the Ekkers’ politics didn’t precisely match his own.

Life didn’t need to be that polarizing, that inflexibly black and white, or that brutally bisected. In other parts of the book, Redford agrees to respectfully disagree with some of the more inflexible opinions of the men and women he met along the trail. But not once is there a hint that he felt inclined to hate them for it. He neither sought, nor wanted to judge anyone in such a harsh manner. All these years later, those values still mean something.

***

Redford himself might have fallen victim to that kind of self-righteous wrath, had “The Outlaw Trail” been written in this kind of polarized environment. One of his own passages, hardly noticed then, would surely have brought him condemnation and exile in 2020.

Among the contentious aspects of the recently created and then reduced Bears Ears National Monument, no topic is more volatile than the past destruction of, and needed protection for the archaeological treasures that are found across Cedar Mesa and southeast Utah.

More than a century ago, when Mormon pioneers first settled parts of southeast Utah, they found these artifacts, thousands of them, abandoned hundreds of years ago, by ancient Native Americans. They found pots and projectile points and burden baskets, metates and manos, and the still intact remnants of their homes. The Mormons, exiles themselves, gathered the artifacts up and they took them home. They were beautiful, no one else seemed to want them, and it seemed to them logical to get them out of the weather. Most thought they were doing something good. Universities even hired the locals to lead archaeologists to the better sites.

In more recent times, professional grave robbers have looted Anasazi sites and even their graves for big profits and to fund a growing illegal crystal meth business in the Four Corners. Others just liked to gather artifacts for their own collections.

Perhaps the the largest and most destructive looting of southeast Utah’s ancient history was sanctioned by the federal government, when it allowed the flooding of Glen Canyon in the 1950s to create Lake Powell. Despite last minute efforts to salvage some of it, most of the history and archaeology of Glen Canyon still lies under 500 feet of stagnating water.

Now, as public opinion changes, many look back on those practices and call it looting, plain and simple, without hesitation. There is no ‘gray zone’ to be considered. Almost 150 years after the Mormons came to the area, their actions are seen in a revisionist’s dark light.

Further, in 2020, the bar of archaeological protection has been raised even higher, and rightly so, to most of us. To even touch or move a surviving artifact from its original location is condemned. It loses its context. To remove them, is illegal. And surely all of this is as it should be.

But even in 1975, when I was already a young adult and a force of eight BLM rangers at Grand Gulch was trying to protect the treasures found on Cedar Mesa, Redford included this passage in the closing chapters of “The Outlaw Trail.”

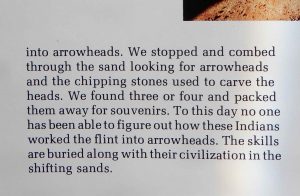

“A.C. pointed to something in the sand. It was a flint-chipping camp, a place where a thousand years ago Indians gathered flint and chert and worked them into arrowheads. We stopped and combed through the sand looking for arrowheads and the chipping stones used to carve the heads. We found three or four and packed them away for souvenirs.”

Souvenirs. He thought nothing of it at the time. He even wrote about it. And nobody objected. Can you imagine what would happen today? If San Juan County residents are judged harshly now for collecting souvenirs half a century ago, should Redford be similarly condemned? Personally, I can’t be that self-righteous.

(And note, I’m differentiating between souvenir collectors and for-profit looters and desecrators.)

Times change. We try to be better people. We can learn from the past, and from its mistakes. But we can also learn from the good that came as well. And the fact that everything…I’ll say it again…everything is more complicated, more nuanced, more human than we ever care to realize.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

A rare balanced assessment; much appreciated.

Nice story, but must you further the polarization by lumping all environmentalists into “love to loath”? I love to read your histories, etc, but tire of your polarized opinions. Many of us can respect the people and still see the need to make changes as times change, to try to stop destruction of our beloved earth when we see it…much as you define Robert Redford.

God I love reading this rag. Thoughtful commentary absent the judgement (what a novel concept in our “age of enlightenment”).

Nice op-ed with good link to your dog centric piece. Evolution happens and it isn’t all so great for the outmoded creatures.

Pamela Quayle: ” . . must you further the polarization by lumping all environmentalists into “love to loath”?”

===

Environmentalist have polarized the world first. To my knowledge the only environmental non-profit organization who even remotely attempts to reach out and find common ground with businesses and land owners is “The Nature Conservancy” (take note I’m not lumping all enviros together) and they are much hated by the Admins of other environmental groups & their followers for doing as any social media page will reveal. Common ground to the average modern day environmentalist is that their opponents must believe and accept everything that comes out of their mouths with questions asked. These modern day enviro admins tend to have a ‘god complex’. They have made their entire careers out of looking for trouble somewhere, anywhere. So you or they shouldn’t be surprised when trouble finds them. Getting arrested and promoting that experience as a badge of honor doesn’t give you a voice, it gives you a record.

My ex worked at the Grand Canyon for a while. He has been either a cowboy or a tree trimmer for over 40 years. Have you seen the documentary put out in 1991 or 92 called The Last Cowboys, narrated by Joseph Campanella? It featured a couple Southern Utah ranches plus one in NV and a segment on rodeo. My ex was in the last segment on the Fish Creek Ranch out of Eureka, NV.

We lived on a hay ranch in Mugginsville, CA in 1979 and I have fond memories of branding time right outside our front door which was an old historic hotel complete with crib rooms, ball room, and a big long bedroom for the miners. Our kids slept there.

How oft we hear those fierce demands to kick the cows off the public lands. What happens then? Will public lands managers be content to let the land thus cleansed of cattle return to its once pristine state? Of course not! How silly! Public lands are managed for wealth generation. And if the cows are gone who decides what the next wealth generating activity will be imposed? Will it be the morally pure environmentalists? And if they were the decision makers would they really be content with leaving the land to recover? Or would some other type of wealth generating activity be invoked as necessary for the forward march of the economy?

As countless examples show, it is industrialism that replaces pastoralism. So, in place of cows, we get industrial tourism. Could an environmentalist with a straight face really declare that the Sand Flats area has enormously improved since the cows were removed? And if it is not industrial tourism, it is oil and gas leasing, or strip mining, industrial parks or housing developments. What all of this shows and has shown from the beginning is the complete lack of a critique of capitalism and industrialist ideology on the part of the mainstream environmental community.

Cows and ranchers are visible and easy targets, a critique of their activities is easy, almost mindless. A critique of the much larger problem of industrialism and its concomitant need for expanding populations – expanding markets – is much more difficult and requires going outside the framework of one’s conventional education to find a critical perspective. So, do we hear even the glimmerings of a critique of corporate capitalism form environmentalists? Heaven forbid, especially when one’s organization is supported by donations from corporate capitalists. Promoting the hatred of cows and ranchers is an easy way to bring the naive into one’s organization. But it also keeps them stupid.

What have ya’ heard, Shane?

Jim has a perspective on the changes in the West that cowboys, city dwellers, and seekers of quiet places should all read and think about. The enormous increase in the number of people coming to Southeastern Utah as a result of the publicity about the National Monuments is resulting in further decay of the very sites that need protection.

Great reading as usual. I was raised in cattle ranches and craftsmen are stewards of the land, and I’ll leave it at that.

Sorry about craftsmen should be cattlemen

I remember the 70’s when we didn’t like cows much. And then we came to slowly realize that the ranchers wanted what I and my friends wanted — open land. Cows were eliminated from the Island during this time. This was during the time the government was pushing to make a paved road around the periphery of the Island in the Sky, Canyonlands NP. We were happy that didn’t happen; the old dirt road down the middle kept out the riff raff and didn’t open the miles of rim to degradation.

I have a vision of a BLM swat team breaking down the door while executing a search warrant at Robert Redford’s home looking for his “souvenirs” (arrowheads). ………. Nah, it’s much easier to break down someone’s door in Blanding where all of those evil multi-generational uneducated Mormon looters are hanging out. What’s the difference between a couple of Arrowheads and 40 or 50 Arrowheads? Evidently the class of people that you happen to occupy at the time the overpowered, unaccountable and morally superior bureaucrats decide that your Arrowhead collection is supremely offensive to the “enlightened” and absolutely politically correct conscience of the correct body politic of our more enlightened, properly degree’d and “correctly educated” political commissars. You mustn’t offend the party now Winston…….Big Brother is actually and in fact watching you.

Oh, I almost forgot…..I think it’s time for me to take Ed’s advice and go piss off the front porch.

Well said. I wish we could go back to the times when AC was alive, where we appreciated the good ranchers/cowboys and could find mutual respect.

One of the things missing from the grazing controversy is wildfire suppression. From my own little bubble, I’ve noticed that the many wild fires in the area are in places where cattle and sheep have been removed from the land. Basques still run sheep around the reservoirs north of Truckee, CA and there have been no huge wildfires in that area. (I take great delight that the Basques have returned to grazing sheep on a now-defunct housing development’s golf course.) Meanwhile, every summer, there are huge fires in the regions south of Lake Tahoe. There are remnants of a ranch that once ran cattle there. Our friend rode in the last cattle drive. The Angora Fire wiped out dozens of homes in South Lake Tahoe where that ranch used to be. Townsfolk sent death threats to TARPA personnel for being the main cause of that fire through their ridiculous and arbitrary regulations. A local Basque restauranteur recalls herding sheep with his uncles around Markleeville, CA where fires threaten that town regularly. The local wild horse advocates spar with the BLM over the right of wild herds to graze in the northern Pinenut Mountains east of Carson Valley. Every summer, you can bet on it, fires char the southern end of that range. A pair of horses died when lightning struck the ground between them. It left a burn mark on the ground. Where horses don’t graze (the southern end of the Pinenuts) lightning creates devastating fires EVERY YEAR! Meanwhile, people in Carson Valley joke that there are more cows in the county than humans. Every winter, there’s the Eagles and Ag event where people can watch baldies and other raptors devouring the afterbirths of calving cows. Coyotes prowl throughout the valley. Deer graze complacency on lawns in Genoa. Bears and cougars follow them and sometimes wander into town. Wildlife thrives in this bovine infested valley where the air is so clean from all those farting cows that we don’t have smog inspections. Does anyone in the environmentalist community even think of studying grazing and wild land fire? Or are they too busy soaking in hot tubs in Sedona?