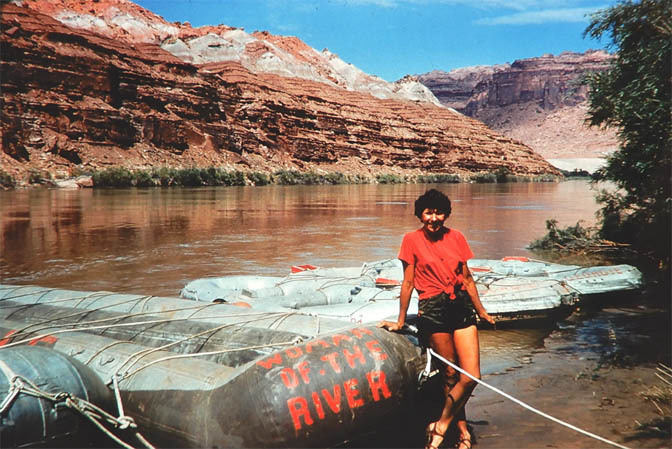

Georgie Clark is single-minded. “The Colorado River is my life, always has been,” she says in a high, squeaky twang. “The Grand Canyon is my home. Forty-eight years now.” Her eagle-like eyes blaze. Year after year, May through September, Georgie runs the river, guiding her rubber raft through rapids and falls, giving thrills to city slickers and nature lovers. On a good day, the waves crest at 15 feet, and when they hit, everyone laughs, screams, and holds on tightly.

The sun soon dries the soaked boatload. “I like it because I’m naturally that way —I like to MOVE and I like to GO.” She speaks quickly, spitting out words. “I like the fact that there’s a beginning and there’s the end. And you meet different people all the time,” she exclaims. “I like people and I like to give ’em enjoyment. I like to show ’em the river. They get a kick out of it.” She pauses. “That’s the way I like it!” It’s a famous quote, her business motto, emblazoned on brochures and neonbright tee shirts.

I book a seat on a trip in early May 1991. She writes me longhand on orange stationery: “I am looking forward to seeing you on the river. We can talk a lot then. Keep your notebook handy. I am so busy between trips that I can’t arrange anything then. I only have three days between trips and work 4 a.m. until 10 p.m. to be ready for the next trip. “I would love to be a part of your book. “Sincerely, Georgie.” She’s a tiny, sinewy woman with turquoise eyes and a platinum pageboy. Wrinkles line her tanned, leathery face. She shakes my hand with an iron grip and welcomes me to the canyon. “I hope you enjoy it,” she says. I assure her I shall.

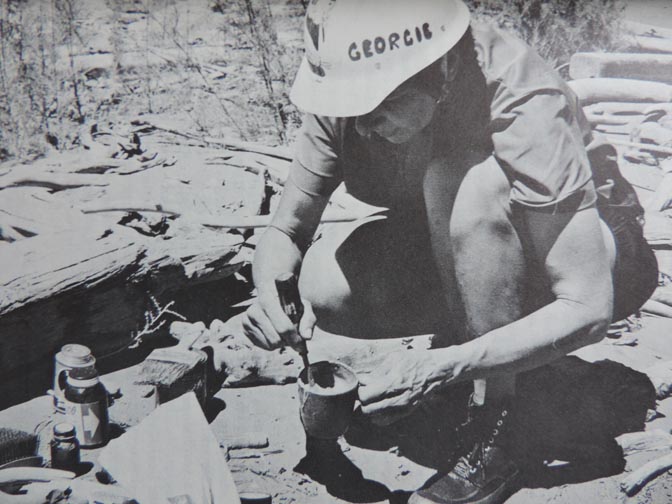

On the river, she is in perpetual motion. For five days, from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., she steers and maneuvers her 37-footlong raft, resting only for midmorning “egg breaks” and lunch onshore. She checks and maintains equipment, instructs her boatmen, oversees preparation of meals, and helps serve them. She talks with people, and after dinner, pours shots of her favorite blackberry liqueur into our coffee. Always in command, she seems to be the last in bed and first to rise. At 4 a.m., she rouses the crew to start breakfast, serve, clean-up, then stow everyone’s gear onboard for push-off at daybreak.

Once on the river, she stands silently at the stern of her raft, left hand on the outboard motor, right hand on a safety rope. Her eyes scan the river, picking the best spots to ride the rapids. When we hit white water, she negotiates fast, efficient passage, avoiding whirlpools, skirting rocks, and twisting in and out of drops and waves. It’s a lot of work for an 80-year-old woman. But she loves it. Georgie is a legend in the Grand Canyon. In 1945, she was the first woman to float down the river in a life preserver. She was the first person to take large boatloads of paying customers down the river, starting in the late 1940s. In 1955, she introduced her own raft, the “G-boat,” a trio of surplus rubber pontoons lashed together in a special configuration, for greater flexibility and less chance of flipping over. Her “G-rig,” with a 30-horsepower Johnson outboard motor, is the biggest and safest boat on the canyon river. It measures 27 feet by 37 feet and holds 24 people.

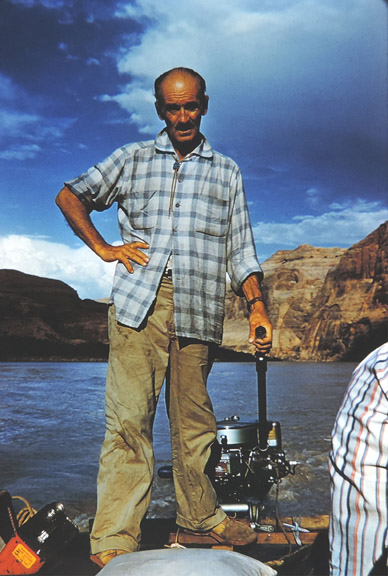

“Everyone watches Georgie run rapids. That’s part of the fun of the river,” says Ron Hancock, long-time friend and boatman. A tall, sun-reddened man with broad shoulders and ready smile, Ron motions toward a group of people watching from shore. Above them tower the red, craggy cliffs of the Grand Canyon. Ron prepares to videotape our run through Hance Rapid, a 30-foot drop at the 76-mile river mark below Lee’s Ferry, Arizona, the trip’s starting point. “Hold on,” he shouts. “Scream and holler and have a lot of fun!” Georgie says nothing, but leans over the motor and peers out from under a red-brimmed hat, her hawk nose in profile, Georgie Clark head cocked to the left, mouth in a faint smile. She steers to the right side of the river. All around us is churning whitewater, and I see what looks like a big drop ahead. Suddenly the raft plunges and pitches, and we’re in the middle of a trough. A sheet of water smashes the people in the bow, and they scream with delight. In the stern, we get pounded by a second wave and water shoots up through floor space. Everything is soaked, including Georgie.

We look like river rats. The people onshore shout, wave, and applaud, and Ron swings his camera toward them, capturing the end of another successful run. We check our gear to make sure nothing has washed overboard—hats, glasses, cameras, binoculars. We’ve been told to anchor everything inside our parkas and rain gear. Now it’s time to take off the life jackets and let the sun dry our clothes. Georgie’s eyes never leave the river. She stays the course, squints into the dark blue water, and relaxes only slightly as we coast into a smooth stretch. Ron’s video will be sold at boat shows that Georgie attends in the winter to publicize her trips. She calls her company “Georgie’s Royal River Rats” and her brochures include clients’ quotes of praise. In the off-season, she patches and paints her rigs, revises the brochure, and buys supplies for the next season.

“I’m so busy, I never think of me,” she says. “I’m so BUSY.” Her voice has a tinge of wonder. “I don’t spend time thinking anything about myself. I do what I want, with the good health I have. My sister Marie used to say if I gained a minute’s time, I’d try to put an hour in it.” She laughs a high, tinny cackle. So you can laugh at yourself? I ask.

“Me? Oh, yeah,” she smiles, showing irregular teeth. “For sure, for sure. That one I can do well.” Her hands are dry and gnarled, her fingernails broken. “I’m all bones now,” she laughs, looking down at her synthetic leopard-skin top and pants. “These were Marie’s idea. I got motor grease on a red shirt once, and Marie got me a whole leopard-skin outfit. ‘Wear these,’ she said. ‘If you get grease on them, it’ll look like another spot.’ So I have!” They’ve become Georgie’s signature. A leopard-skin flag flies at the stern of her G-rig. Tonight we’re sitting in captain’s chairs at campsite, a sandbar that stretches 100 yards. Tamarisk trees with frond-like branches separate us from the canyon wall 40 feet back. The crew is preparing dinner and people are unrolling their sleeping bags.

The sun sets quickly and soon we are in shadow. Georgie drinks beer from a can. “I worked all my life. Born on it, raised on it,” she says rapidly. “I’m a workaholic. If I’m not working, I practically feel uneasy. I’m used to doing things a certain way. And I always did manage to work for myself. “I worked in real estate and at things where I could be my own boss. No matter what, even in the Depression, I was determined to work for myself, come hell or high water. I raised my own daughter when there ain’t nobody around.” She smiles and looks pleased.

Growing up poor made her strong. “We ate simple food: celery, beans, cab bage, and prunes. We ate rice, cucumbers, raw potatoes, baked potatoes, and tomatoes. All the things they say are GOOD for you now. We didn’t have pies or cakes or anything sweet, because we couldn’t afford it.” After marriage, she graduated from high school, gave birth to a daughter, and headed west to explore deserts, canyons, mountains, and rivers, including the Green, San Juan, and Colorado. She hiked, climbed, swam, and paddled. She attributes her stamina to good genes.

“You inherit things. I believe you inherit TERRIFIC,” she says earnestly. “I don’t need glasses and my hearing is good. I’m always active. I’m Irish and English on my mother’s side, French on my father’s. My mother used to say, ‘That’s French and alley cat.’” She laughs delightedly. “Of course, that makes you sturdy, because, anybody knows, animals or otherwise, these are the sturdy ones. Not if you’re a thoroughbred, you’d never be sturdy. I like the mutts, I pick up the mutts.” She grins. Georgie always has had pets. Three cats and a dog live in her mobile home in Las Vegas, and she lavishes attention on them.

“I feed ’em and pet ’em and let ’em sit in my lap,” she says. “I always turn on the TV for ’em. The cats like to look at TV. Not for me, I don’t watch. The first night I’m back from a trip, I stay up to keep ’em company, even though I’d like to go to bed. “My sister used to accuse me of liking animals better than people, because I RAVED for them first,” she goes on quickly. “My family’s all dead: mother, brother, two sisters, and daughter. My father left us early on. My mother never talked agin’ him.

He was a Frenchman from France and she said he just simply should not have been married, that he was a party guy. So we didn’t know anything about dads. When people today yak all this stuff about ‘You should have two parents,’ I just laugh, because my mother was so terrific.” She doesn’t mention two former husbands. I read in her book, Georgie Clark, Thirty Years of River Running, that in high school, she married Harold White, the father of her daughter. Later they divorced and she married James Whitey. “‘He eventually went his way and I went mine,’” she writes. “‘Although I have been married most of my life, I’m afraid I’ve always been quite independent. I have always lived life my own way, no matter what my husband thought. Of course that’s not the way to get along with a man, but then that was the way I have always been.’”

Her animals are her family now. “I like pets really as good as humans. Anyone can benefit from pets,” she goes on enthusiastically. “It’s too bad when people don’t like animals, because animals, I think, are the BEST thing on earth. When I have a dog, I usually have a yard where he can run free. “And cats,” she exclaims. “I love cats because they will have freedom, even if they starve to death. I always say I’d be like the cats. I’ll go sit on a fence and howl, even if I starve to death!” She laughs hard. “Animals treat you just like you treat them. You’ve gotta have the interest, put them BEFORE you. Whatever you get, take care of it.”

She looks fierce. Georgie is a loner. Except for a couple of good friends, including her office manager, she keeps to herself. “I like to live alone,” she says. “I don’t even let anybody know the address. I don’t NEED anyone, so I’m never lonely. “My mother taught me to be self-sufficient. She always said, ‘We’re poor, there’s no down.’ And she never downed me. She told me to go for it! When I was thinking of going down the Colorado River in a life preserver and people said it couldn’t be done, my mother said, ‘Go for it! I’m sure you’ll make it.’” The smell of grilled meat floats over to us and Georgie excuses herself to oversee dinner. Hungry boaters have lined up with their cups and plates. Appetites run high on the river.

Later we talk about her daughter Sommona Rose, who was killed at the age of 15. “I named her after a French woman I knew,” says Georgie in a loving tone. She describes how she and Sommona Rose did everything together: traveled, hiked, climbed rocks and mountains, even learned to fly together when Georgie trained as a pilot in the U.S. Ferry Command in World War II. They were riding bicycles on the California coast when a drunk truck driver hit the girl, killing her instantly. The police tracked the driver, but Georgie declined to bring charges. “It wouldn’t bring her back,” she says quietly. For a few weeks, she lived in depression.

Then she met Harry Aleson, a fellow Sierra Club member and explorer. Aleson showed her slides of his hikes in the canyon country of Arizona and Utah. Georgie was hooked. A new world opened up and she suggested they hike it together. She and Harry became friends, and over the years, they covered many miles. Twice they floated down the Colorado River of the Grand Canyon.

“I was out here on the river 25 years when there was absolutely nobody here,” she recalls. “All the people on my trips depended on me, period. There wasn’t nobody else. There was no helicopters, there was NOTHING down here. The park rangers were not here. That was before the dams were built. These were long trips, one- and two-week trips.” At 80, she is strong in body and mind. She takes pride in not being emotional. “My mother taught us not to cry. We don’t have that emotion. I don’t have it about marriage or nothing. I was never one who had stars in my eyes. I was not one who grew up wantin’ or being man-crazy. In fact, the men had to prove theirself to me! “Oh, sure,” she goes on. “I miss the people who’ve died, like my sister Marie, because we were peas in a pod. But there’s no way I was going to cry, because I don’t know HOW to cry.

“I don’t go to funerals. I don’t see funerals at all, because when people are gone, they’re gone. They’re out of it. You do whatever you want to do for ’em in lifetime.” Georgie has been “doing for” people all her life, starting with her older brother and sister. “We were always taught that no matter what, you helped one another and supported one another, good or bad,” she says. She’s helped Navajo Indians who live in the Grand Canyon. At Christmas, she persuaded friends and businesses to donate food, candy, and clothing, then trucked it herself to the reservations. “I like the Navajo,” she says quietly. “I could’ve been a Navajo, lived as one. “The Navajo feel the same way I do about life, about nature and sex. If they need it, they do it. That’s that. They don’t use all this build-up, with fancy dress and undress. This is RIDICULOUS. The Navajos never did such a thing. It flows natural. When I was young, I didn’t even think of sex. If I wanted anything, I took it. If I didn’t, forget it!”

She laughs. “There’s no emotion in sex, there’s no nothing. It’s like eating. If you need it, you need it. If you don’t, to heck with it. “I keep busy,” she says. “People need to be busier. If they’ve got time, they think about themselves too much. Then even any little thing, they can FEEL it, and that little thing gets bigger. If they got too much time on their hands, they’re going to think about their ills. Naturally! “A lot of older people don’t have interests,” she continues quickly. “They go into condominiums, things are done for ’em, they don’t have the interest. This traveling around by bus and all, tours, any of this stuff, that’s for the birds.” Her voice is impatient. “I could have less interest in a bus trip than the man in the moon!”

At home in Las Vegas, Georgie drives blind people on errands. “I think of all things on earth, the worst is not being able to see. So my sympathy has always been terrific for them.” She donates clothing and leftover food from the river trips to a local mission. “If I get two minutes, I do somethin’ like this,” she says. She reads U.S.News and World Report, Reader’s Digest, and The Wall Street Journal. “Not the financial stories,” she says quickly. ‘I’m not interested in that. I like their stories on the actual things in life. When they tell a story, it’s really stated very carefully. They have a lot of stories on different things.”

Later, she confides, laughing, she uses the newspaper to line the animals’ litter boxes. Her religion is the Golden Rule: “‘Do as you’d be done by,’ my mother always told us.” Nature is also a religion for her. “The Navajos are like that, the Navajos ARE nature,” she explains. “Their original belief is complete nature. I could come on the river being a Navajo, because I’ve been with Navajos. I used to give ’em parties and get food and all for ’em, in the old days before there was civilization. I like the nature, I believe in nature, and I think everything’s the way it’s meant to be.”

She’s healthy, lives on fruit, vegetables, cheese, and bread. She takes no vitamins. “I think they would be an off-balance to you,” she says adamantly. “I don’t eat a lot. As a youngster, I didn’t get a lot of food. None of us did. I never smoked, because I couldn’t afford it.” She likes beer and an occasional glass of blackberry liqueur, but only at night. A new law forbids anyone to drink and operate a boat on the river. She says some river runners used to drink beer all day and became dangerous to other boatmen. Georgie has a number of young friends in river-related businesses. But she believes most young people lack the strong fiber of her generation. “I look at kids today and feel sorry for ’em. They don’t have a mother like mine, who taught me to be self-sufficient. They aren’t bad. It’s just a case of the times. Times change and they’re going with the times. It’s simply the different day they’re raised in. They don’t know different, so what would they do any different?”

She loves children and welcomes them on her trips. “I wish that more families would bring their children,” she says. “We get some, but not as many as I’d like. Sometimes I’ll get children of the Girl and Boy Scouts who hiked with me in the early days.” Georgie seems to be at peace. What’s the key? I ask. “I see the good in everybody and just forget the bad,” she replies. “I just forget it, pick out the good and leave the other alone, ’cause everybody’s got good and bad faults. It just depends on the person who’s judging.” When she turned 80, friends and admirers honored her. “Ted Hatch of Hatch River Expeditions put on a party, a great big party!” she exclaims. “They had 400, 500 people at Marble Canyon, at the Hatch Warehouse, and it was a real blow-out! No one will ever forget that party.” She cackles. “There was a guy with long blond hair in leopard-skin cape and tights who jumped out of a cake that came down from the ceiling. Then he took me on a ride in a Cadillac. I’m not so sure I liked that, because he liked to drink,” she whispers. “That guy loves a WILD time, that guy loves a wild time.” She shakes her head and smiles. “Then he drove me up in the hills above the warehouse, and all of us watched some fireworks. They put on a real show. Yeah, it was SOME party.” Her eyes glisten and she grins.

Georgie Clark died a year after Anne’s trip and interview, in 1992.

Anne Snowden Crosman is an author and free lance journalist. She teaches memoir writing and edits books. Her earlier book “Young At Heart: Aging Gracefully With Attitude” (2003, 2004, 2005) won a national Benjamin Franklin Award and a Washington Irving Book Award in Westchester County, NY. (This story was a chapter from it)

She was the afternoon host for “All Things Considered” on KNAU, Arizona Public Radio, Flagstaff, AZ, and a correspondent for CBS and NBC Radio Network News in NY, Washington, and Geneva, Switzerland. She freelanced for The Christian Science Monitor, The Washington Post, and Newsweek. Anne lives near Sedona, Arizona.

TO COMMENT on this story, please scroll to the very bottom of this page.

HERB RINGER, EDNA FRIDLEY & CHARLES KREISCHER

Very interesting story about an interesting woman.

Great read. Also inspiring to this recently retired workaholic.

Every young person should read this article or, even better, learn more about Georgie White’s life to understand the real definitions of ‘hardship’ and ‘hard work’. Her life story should be an inspiration to all of us.

I first came across her name last year when looking into the ‘We Three’ river runs involving: K.Lee; T.Nichols and F. Wright.

When I read that Georgie had floated the Colorado in a LIFE JACKET I, firstly, chuckled and, secondly, was awestruck. This woman had bigger balls than I’ll ever have.

There’s a great interview with her from, I think, 1991 out there on the interweb.

Did she fill her rafts with assorted tinned food and let the punters take a lucky dip? I don’t know.

Did her customers lose 14 pounds during a ten-day trip? Probably not.

Her innovative G-rigs certainly upset the more ‘traditional’ river runners though and have been copied and and adapted ever since.

After accompanying Georgie on the Colorado River and reading the book she’d written, my late husband and I made sure we attended her funeral in Henderson, NV. We were appalled that maybe 10 people were in attendance! How soon people forget–her strength, her ability, her kindnesses to so many!

From what I’ve learned about her, she probably would have been delighted that so few people attended her funeral.

I envy Georgie’s courage to live such an adventurous life. She lived without the chains of an office bound by four walls. She didn’t bend to the dictates of a man or boss. What a woman!

Another is a long line of tough, savvy trailblazing women of the West! Profile in adventure!

Extraordinary woman. I admire her strength in adversity, poverty, and grief from losing her precious daughter. She triumphed over it all. Thanks for writing about her.

After reading this again, I realized her profound philosophy of life and strong positive attitude. Very inspiring. Valuable traits that very few people have, and I wish I

could have. Thanks for re-running this article.

Teriffic lady! Gail and our Grandson toured on the Colorado with her. Her boatmen that year were California firemen who took their vacation time with Georgie year after year. They obviously enjoyed doing river running with her. She was a legend and well deserved.

I remember launching from Lee’s Ferry the morning after Georgie died. We toasted her every night!

My dad and I took her rubber-raft Glen Canyon trip in 1958, when I was 11. We met up at Knab, Utah, went down the canyon in three rubber rafts, and ended up in Arizona. It was just before the Glen Canyon Dam was built and Powell Lake created, flooding out the course of the river. At that time, it took 5 or 6 hours to walk in to Rainbow Natural Bridge, and the same to walk out. But it was an easy walk because in was on those flat, sedimentary sandstone rocks, and in the shade of the tall rock walls. I just found my army-surplus Canteen inscribed “July 3, 1958.” In 10 days, we met no other people except a group of young Mormons taking the same trip. I found chips of flint still lying on the rock where they fell when a native arrowhead maker worked on a stratum above, hundreds of years ago. All this was lost by the flooding of the dam.

Loved this story! Your a gifted writer!