AND AN ANALYSIS OF THE LIMITED 54 PAGES OF FBI DOCUMENTS RECEIVED BY THE ZEPHYR via its FOIA REQUEST

NOTE: If you are a regular Zephyr reader, you are familiar with my intense interest in a crime that occurred near Moab almost 62 years ago, and my efforts to fully understand what happened on that dark Fourth of July along the Dead Horse Road. To new readers, who want to understand this third chapter, I’d strongly urge you to take the time and read two articles that I have written about the incident. You can find them here and here. Be advised they are long and detailed. The main story is almost 25,000 words long. The follow up, published last summer, is about 8000 words.

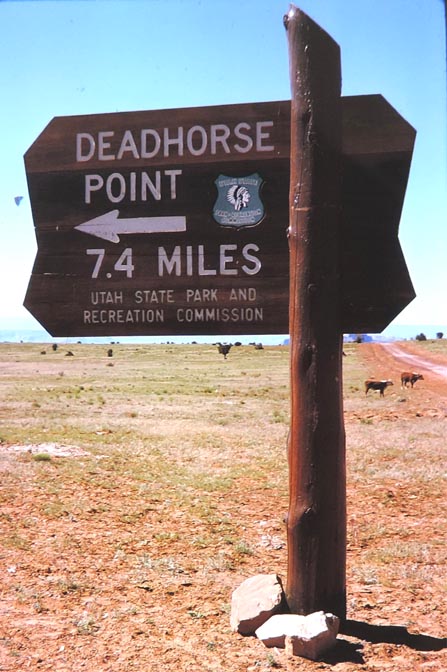

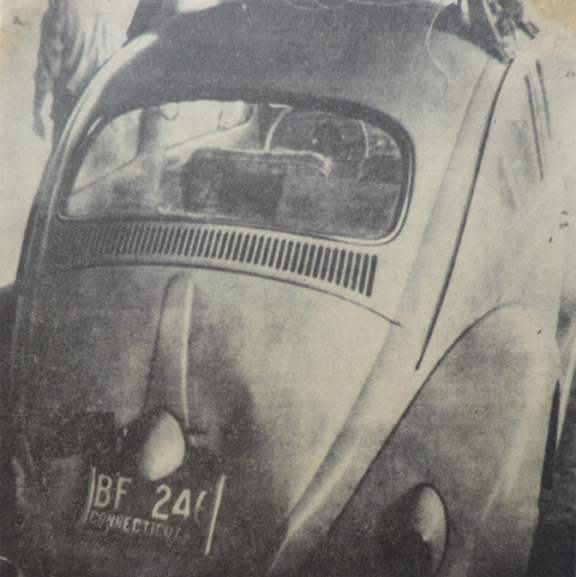

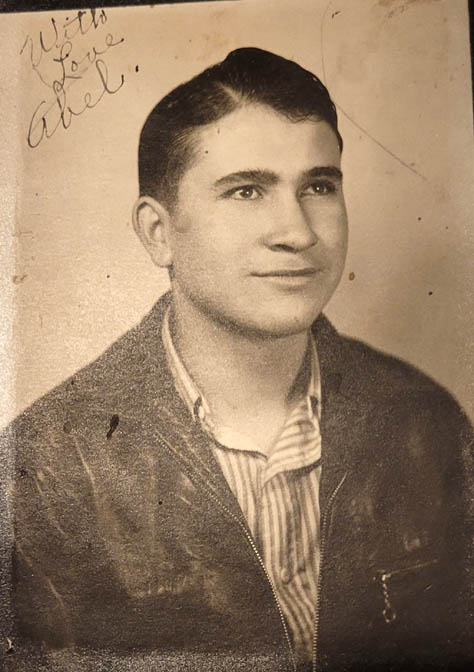

But to provide a brief summary, on the evening of July 4, 1961, Charles Boothroyd, his fiance Jeanette Sullivan, and her daughter Dennise, were returning to Moab after a long hot summer day exploring the canyon country in a VW Beetle. They were in the first week of a vacation and had traveled across the country from their home in Connecticut. At Dead Horse Point, they met a man named Abel Aragon, an out of work coal worker from Price. They chatted amiably for a few minutes. After sunset, they all left the viewpoint and Aragon race past them on his way back to the main highway.

But a few miles later, they spotted Aragon’s car pulled by the roadside. The hood was up and Boothroyd stopped to offer assistance. Suddenly Aragon reached into his car, pulled out a .22 rifle and demanded their money. Boothroyd threw his wallet on the ground, but Jeannette was furious. She took the $250 money roll from it, tossed a twenty dollar bill on the ground and started to walk away. Aragon went mad—he shot Jeannette in the back of her head; she died within an hour. In seconds he fired two rounds into Boothroyd’s face; he fell to the ground. Aragon assumed he was dead too.

But he had forgotten about the girl. Dennise was barely 15 and didn’t know how to drive. She had watched her own mother shot to death from the back seat of the car. Now she frantically tried to escape in her mother’s VW Beetle. Aragon went after her, rammed the small car several times, and finally forced her off the road. At that precise moment, an inbound car driven by an oil field worker named Leonard Brown was less than 30 seconds from encountering the VW and Aragon’s Plymouth. If you know the area, Aragon must have heard the car coming up the steep grade from Seven Mile Canyon, and even its headlights. What did Aragon do?

Brown saw Aragon pass him, as the killer raced for the main highway. Twenty seconds later, Brown saw the VW but thought nothing of it. But in less than a mile, he came across Boothroyd, bloody and barely conscious, collapsed in the middle of the road. Brown realized there was another victim, and he transported both Charles and Jeannette to the Moab hospital. Because he worked for the Brinkerhoff Oil Company, Brown luckily had a radio telephone in his car, and was able to notify Moab law enforcement.

Incredibly Boothroyd was conscious and could even describe the shooter and a partial of the license plate. They saw the VW and Boothroyd yelled to stop. He explained that there was a girl missing. Leonard checked— it was empty. ‘My God, Charles thought; he kidnapped her.’ Brown encountered a deputy at the highway junction and Brown told him about the girl and the VW. He told the deputy. “He must have taken her.” The deputy led Brown and the victims to the Moab hospital. It was hours before anyone checked the crime scenes. From that moment, there was never any thought other than the terrifying notion that Aragon had kidnapped the girl. By midnight Sheriff John Stocks had called the FBI in Salt Lake City.

A massive search followed, and it took days to learn that Aragon had driven to the remote Polar Mesa in the La Sal Mountains. But no one saw the girl. On Friday, July 7, as FBI agents drove north to Crescent Junction, they spotted a car. It was coming east on the Dead Horse Point road where the shooting had occurred. Incredibly, when they caught up with the car, both agents realized it was Aragon. (By now law enforcement had been able to identify the shooter) They waited until Crescent Junction to make the car stop. But before agents could arrest him, Aragon shot himself in the head with a .22 pistol. He died an hour later. Dennise was not in the car. Her body was never found. To this day, no one knows what happened to Dennise Sullivan.

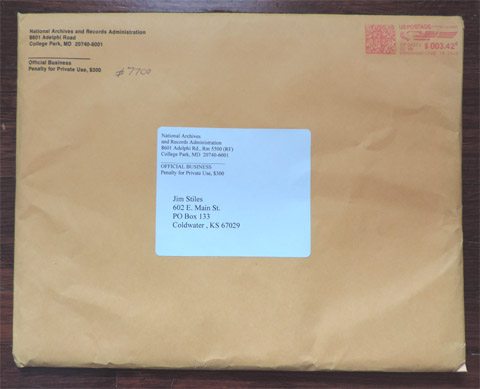

THE ZEPHYR FBI/FOIA REQUEST: FINALLY A LIMITED RESPONSE

Many of you have followed this story, my research, and my efforts to obtain the original police and FBI reports and documents related to the crime. The Grand County Sheriff’s office had nothing, but suggested that the FBI might, since that agency took the lead role in what they perceived to be a kidnapping. In July 2021, I filed a FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) request with the FBI. After several weeks, they replied—nothing. But they suggested that many of those documents may have been turned over to the National Archives & Records Administration (NARA). So I filed a FOIA with them. I was advised that because of covid, I should expect a long wait. Thirteen months later, I wrote to them again. NARA advised me that they had indeed found 473 pages of records related to Abel Aragon, the shooter, and Dennise Sullivan, the victim. However the archivist told me that each page would need to be reviewed for “privacy and national security issues” and that the time it would take to complete that process was “approximately 39 months.” THIRTY NINE MONTHS.

What followed was an online argument between me and various NARA staffers. The 473 pages dated all the way back to 1942, which suggested that many of the reports were about Aragon’s wartime service and his extraordinary heroism on Chonito Ridge in Guam (more on that story in a minute). What I really wanted were FBI records related to Dennise Sullivan’s disappearance. Specifically I explained that I was seeking any information that might include an inventory of Aragon’s car, after he was stopped by FBI agents on Friday, July 7. I wanted to know if there were reports that proved Dennise had ever been in the car. Surely there would be physical evidence, signs of a struggle. Blood evidence and fingerprints.

Finally, a very reasonable NARA archivist, Diana Calgano, emailed me and proposed a compromise. If all I wanted was information related to the contents of Aragon’s car, it would reduce the number of requested documents to 54 pages. And it would only include those reports filed in the 14 days after the crime. If I agreed, she could expedite the review and I could receive them in less than a month. But there was a caveat. Another FBI folder existed, of much greater length, and was written after July 18. If I insisted on that file, I could still expect a very long wait. I reluctantly decided to accept her compromise and hope that it could produce new and important information. In early February, the package came. 54 pages. I spent the next day reading and re-reading the documents. I discovered new information, some tantalizing clues, but no smoking gun. In one report, the information offered was particularly frustrating.

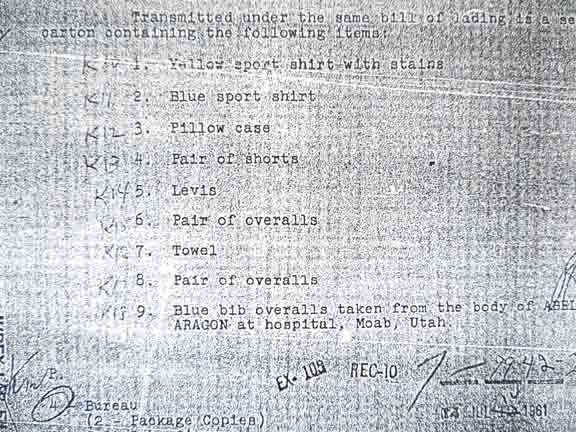

In some ways, what was not in the documents was more revealing. The FBI listed all items found inside the car. It wasn’t much (see list below ) In the glove compartment were three unmailed letters, two to Aragon’s wife, the other with his name in the return address on the envelope. It contained three twenty dollar bills. . But the reports don’t include the content of those letters.

One tantalizing but frustrating piece of information was a notation that two sets of fingerprints had been lifted from “the top of the right door.” It’s no more specific than that. The report doesn’t even clarify if the prints were on the outside of the car door or inside. The document continues that the FBI would compare them to Aragon’s, whose body was in custody. Then it noted that a comparison to Dennise’s prints would be possible “if her body is ever found.” It was absurd to suggest that the only way they could compare the prints was to find her body. Dennise’s prints would have been all over the Volkswagen. It would have been easy to distinguish between Dennise and her mother.

What’s more bewildering is the realization that these were the only prints they found or reported; an extensive examination of Aragon’s car was not deemed necessary. What becomes apparent is that the kidnapping assumption was so deeply entrenched, so early in the investigation, that no one felt there was a need to prove she had been in the car. Remember Sheriff Stocks called the FBI barely three hours after the crime occurred. Both Boothroyd and Brown assumed she’d been kidnapped when they saw the VW and discovered she was gone.

In fact, by law, the FBI could only be involved in the investigation of this crime if it was indeed a kidnapping. Further, they could only take the lead in the investigation after 24 hours, and finally, there had to be the possibility that the victim might be taken across state lines. Then it became a federal offense. Otherwise the FBI had no authority in this case at all. But the FBI agreed to send agents to Moab in the morning so that they would be in place and ready to take charge when the 24 hour limitation expired.

*****

In Salt Lake City, where Charles Boothroyd was recovering from his gunshot wounds, he was able to speak to the media. He had talked about meeting Aragon earlier that evening and how amiable the conversation had been. But at the scene of the shooting, Boothroyd said that it was as if he had become “someone entirely different.” And he could not stop thinking about the girl.

“I wish they could have found Dennise, but it’s one of the nightmares I take home with me.” Pondering her fate, he found himself hoping that she had met a quick and “merciful death.” He told reporters, “I only hope that he remained in the same frame of mind that he was in when he killed Jeannette and shot me. Maybe then he killed Dennise right away.”

The alternative was unbearable. “It would be terrible if he had left her alone in the desert to die.” Boothroyd was overwhelmed by the thought of it.

Others shared his sentiments; as horrible as it was to imagine, members of the Boothroyd and Sullivan family could not bear to imagine the prolonged terror and torture that Dennise might have endured before the end came.

“THE OTHER VICTIMS of JULY 4, 1961”

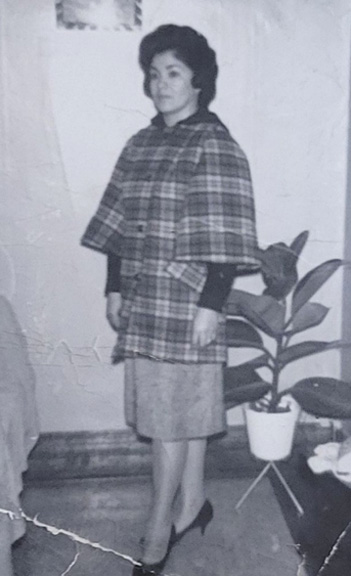

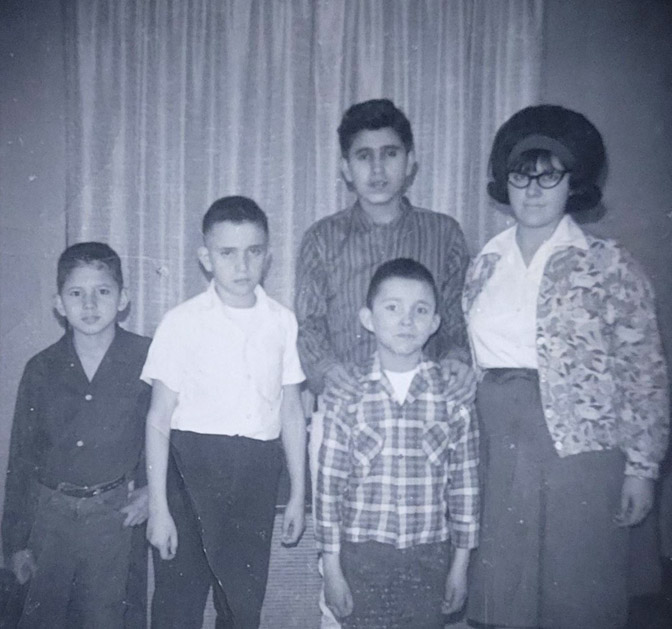

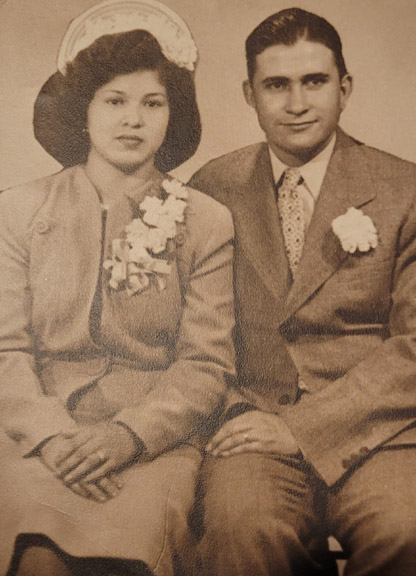

And there was another family praying for Dennise and trying to understand how any of this could have happened. Abel Aragon, in addition to being a war hero, was a family man. He and his wife Eva lived in Price, Utah and had five children. He loved all of them and was a respected member of the community. Eva tried to spare her children as much of the details as she could. But the news was all over town and there was no way to protect the Aragon family from the kind of gossip and blame that comes with an event like this. There were already rumors and whispers and talk of revenge against the family.

That week, Alex Bene Jr, the editor of the local paper, the Sun Advocate, wrote a poignant editorial about the week’s stunning revelations that had shaken the community to its core. In part he wrote:

Another tragedy which screamed headlines throughout the land has struck southeastern Utah not only for the Sullivan family of Connecticut but for a Carbon county family. We do not condone the actions of Abel Aragon in this instance but what are we going to allow to happen to the innocent family left by Abel Aragon. How are we going to explain to our children so that they will not make heartbreaking remarks to the children of this family?

We can only ask ourselves the question: “Why do such things happen to an apparently normal person?” When a man, who has served his country valiantly in time of war, has saved other people’s lives, has loved his wife and children and tried hard to provide for them, to give them a good home, and to rear them to be religious law-abiding citizens, commits murder, can such a person be in his right mind?

The Aragon family needs the tolerance and understanding of everyone in the community. Can’t we all try to ease their pain in giving them the compassion and understanding they so desperately need?

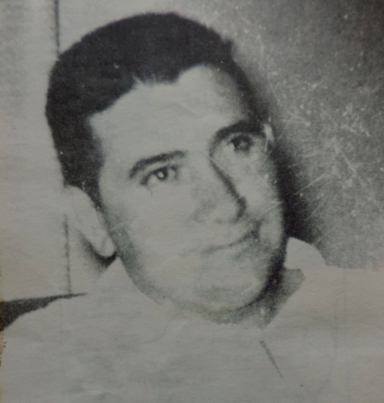

Front: James (Jimmy)…1961

Earlier, he had told the Deseret News that Aragon “had become despondent, couldn’t find work in the mines…it was the only thing he knew.”

Jeanne Sullivan, the surviving daughter, had stayed with her grandparents while her mother and sister went West. Jeanne was only four and it was decided she would stay with her maternal grandparents. It was impossible to tell the truth to a child. But eventually the grandmother had to tell Jeanne that her mother and sister were never coming home.

But years later, when she was old enough to learn the truth, Jeanne and her grandmother Grace discussed the events of that day and, later, Charles offered his own recollections. He stayed in touch with Jeanne for years. Though he never spoke of it otherwise, he must have felt he owed it to Grace and Jeanne. Over the years, Grace sometimes spoke of “that poor, poor woman.” At first Jeanne thought she was remembering her mother and sister, but that’s not who she meant. Grace was thinking of Eva Aragon, the murderer’s widow. Grace tried to impress upon Jeanne “that there are two sides to every tragedy, that we need to show compassion even in our own suffering.” That lesson meant everything to Jeanne and made it easier to live with the loss. As Jeanne recalled later, “because of that, we never hated Abel Aragon for what he did.”

Decades later, in the course of this research, both granddaughters of Charles Booththroyd—Carolyn Boothroyd and Linda Boothroyd Lazaroff, and Jeanne Nabozny, the surviving Sullivan daughter expressed sympathy and compassion for the Aragon family, and even Abel himself. As we all learned more about his wartime traumas and the years of pain he endured later, and his struggles to support his family, it was impossible to hate the man. He was no Charlie Manson. It’s a tragedy that is almost impossible to grasp. Much less to define. It’s difficult to forgive the crime. But as for Abel Aragon himself, it’s more bewilderment. Sadness. Confusion. It would be coldhearted not to feel sadness and sympathy for the man — and even forgiveness for Abel Aragon’s crimes.

*****

For the last two years, I knew there was a vital part of this story that was missing. Like I’ve said so many times before, what about Abel Aragon’s family? What about his wife and five children? I had read the editorial in the Price Sun-Advocate, written the week after the murders, and I wondered if it was already a plea to their fellow citizens in response to a backlash from the community. How did the Aragon family cope with this insane crime?

But I had no idea how to contact the Aragon family. And if I did, would they even want to talk to me? Even worse, had they seen my articles and resented the fact that I have dragged up this awful piece of history from 60 years ago? I resigned myself to the idea that it was one part of the saga that was beyond my reach. But last November, I opened my email and was stunned to see an email from a member of the Aragon family. At first I was almost afraid to read it. Had I opened old wounds unnecessarily and caused them even more pain?

I opened the email. It was addressed to “To whom it may concern…I know that there is a great likelihood that this won’t find the right person and that this is a shot in the dark, but I was wondering if there’s a way that I could provide some information on a topic that Jim Stiles has been writing about for many many years.”

I read on…

“I’m interested because the man that was the suspect, Abel Aragon, is my grandfather. I’ve read Mr. Stiles’ previous articles about the story as well as his update that was published on May 15th, 2022. While I don’t know everything that happened that night and I can’t answer most questions, I would like to offer a few thoughts on a couple of things, if he would be willing to listen. I know that there’s a great effort to try and understand what led to my grandfather doing this.”

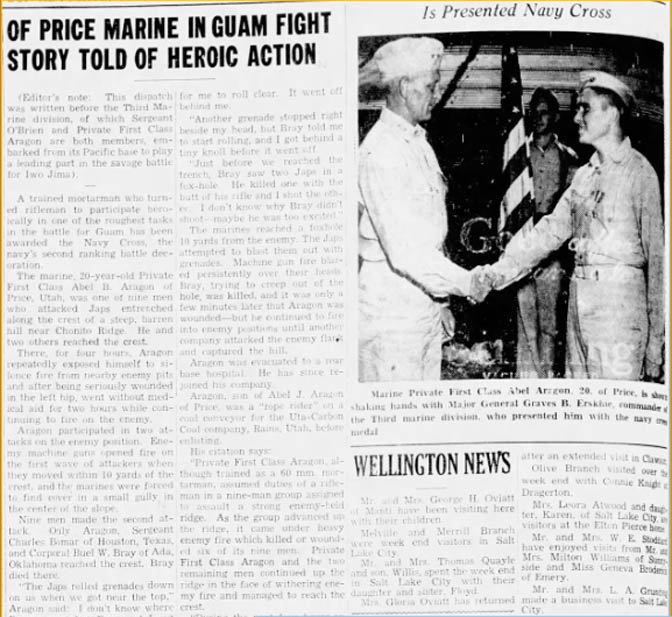

Front: Rebecca (Becky), Abel (Abe), Arthur (Art), Richard . About 1956

She continued…

“I’d like to make it very very clear to anyone who may read this email that I am in no way condoning what my grandfather did. For the majority of my life, I had no idea that any of this had even happened. I didn’t know much about my grandfather but I always assumed that was because it was a hard thing for my dad to talk about since he was so young when his father died. I assumed that it would be hard for anyone to talk about their father dying when they are that young. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I found out, accidentally, what truly happened with my grandfather.

“While I was never lied to about what happened with Able Aragon, I was also not told everything. People always omitted the horrible acts he made in the last few days of his life when they would tell me of him. I was told of the amazing parts of him and of the war hero. The man that loved his wife and children and did everything that he could to provide for them.”

“Since learning of the story of July 1961, I have had the opportunity to talk with a few members of my family that knew about this and could provide some more insight to me regarding the crimes. They were able to tie in what I already knew about him to the things I had just learned. About the man who came home from war and was not provided with proper care and resources through our country’s VA Department to adjust to civilian life. His service in the military led to mental health diagnoses that we left untreated by our government. Ones I believe played the biggest part in the crimes that weren’t discussed in these articles. I’d also like to give a little background on how the events that unfolded also affected Abel Aragon’s wife and children. What their life was like for decades after their father committed these crimes and after he committed suicide. Ways that they’re still affected to this very day. I know that what my grandfather did was inexcusable and there is no way to ever rationalize what he did, but I would just like to fill in some other parts that I believe were left out because Mr. Stiles was never able to talk to someone in the Aragon family.”

I immediately wrote back and explained that if anything, I was hoping I might hear from a member of the Aragon family. One part of my story that she took issue with was my suggestion in the original article that Aragon suffered from a condition called “Intermittent Explosive Disorder.” She felt that was incorrect and further in this narrative, she explains why. What follows is much of the content of the emails I received. I had considered taking the information and rewriting it myself, but I decided it would be much more powerful if the story was told directly by a member of the Aragon Family. Here in part is what I learned…

“My grandfather had 5 children; Arthur, Abel, Richard, Becky, and James. Art passed away on December 19th, 2006 from a car accident while leaving a mine in Carbon County. Becky passed away on July 3rd, 2012. She was extremely sick when she passed. She had been sick for many many years with various illnesses. Doctors never found out what it was exactly before she passed, but on imaging, she had a black mass over her lungs and heart.

“My Grandma Eva passed away on September 2nd, 1998. She battled ovarian cancer that had spread to her liver. The surviving children, Abe, Jimmy, and Richard, all have a lot of health conditions themselves. In 1961, my grandma Eva was working for the city of Price. She started off as a social worker and eventually she worked up to a case manager position. After my grandfather died, she worked full-time for the city as well as doing side jobs whenever she could find them. She busted her ass to provide for her children but they still struggled. The oldest children ended up working early in life so that they could help provide for their family. Grandma Eva ended up remarrying and having another daughter, Ellena…. But it wasn’t a very loving relationship though. He beat her and there were times when my father and his siblings would go to the house and find her unconscious and bleeding on the floor because of how hard he would hit her. He was a violent and drunk man.

“He also routinely attacked Eva’s children while drunk. I know there were many fights between the children and Money. Many of these ended with Price police arresting Money for domestic violence against his children and wife. When my grandmother started to get sick, he all but separated from her. He wasn’t going to support her through her illness. She ended up living with her son after she received her cancer diagnosis. She wasn’t able to get treatment because by the time doctors found it, it was much too progressed and there was nothing for them to do for her. It was her son and his wife who cared for her until her passing.

“After my grandfather committed the crimes and killed himself, my father’s family dealt with a lot. My grandmother Eva and all of the kids faced backlash from the community in Carbon and Emery County. Becky was absolutely tormented by them. It wasn’t just name-calling or typical rudeness that you would expect to follow. She was bullied, beaten, and raped multiple times by members of the community.

“This was all reported to Price Police but it was quickly made known to the family that nothing would be done because of who her father was. My family was left to completely fend for themselves. Becky would go on to become a mother and wife. She was a hard worker who went on to become a coal miner herself as well as a journeyman heavy equipment operator, and belonged to the Operator Engineers Union #3 of Salt Lake.

“People would talk about how she was out there working with all the men and giving them a run for their money, but what they didn’t see was the dark trauma that she dealt with from the people who knew what her father had done. This put a strain on her relationship with her children. She’s not here anymore to tell you of her life and what she experienced and what she knew. But I do know that she did NOT talk to her children about my grandfather.”

“Arthur also dealt with a lot of backlash from the community but not in the same way as Becky. He was soon to be drafted into the Vietnam War but his brother Richard chose to make the sacrifice to reenlist so that Art wouldn’t have to go. Art would become a miner and had several children.

“Abe worked in the mines for a few years after he graduated high school. He would soon be drafted into the Army and would be sent to Vietnam…Abe still lives in Price but he is extremely sick. He was exposed to Agent Orange while in Vietnam which caused a lot of health conditions. In the last 5-7 years, his health has drastically gotten worse. It prevents him from being able to eat food. He has a feeding tube to provide nutrition. He has Parkinson’s Disease, also from being exposed to Agent Orange during his service. He is completely bedridden. He has nurses who take care of him and attend to him, but he is in hospice care. He’s extremely weak, only around 90 pounds, and doesn’t know or recognize the people around him. I’ve never heard him talk about my grandfather before.

“Jimmy also went on to serve in Vietnam, although he was there for the very end of the war. Similarly to Abe, he was also exposed to Agent Orange. His disease hasn’t progressed nearly as much as Abe’s but he also wasn’t exposed to as much Agent Orange. Jimmy came home from the war and started working in the coal mines in Price as well…One of his children knew my grandfather had done something but he didn’t know the extent of the story….Eventually Jimmy told them that (Abel) got sick and died and left it at that.

“Richard Aragon was only 10 when everything happened with his dad. Growing up, he talked a lot about how Becky was bullied so relentlessly and the fights that he and his brothers got into trying to protect her and my grandmother. He didn’t get into the details about why they had to be protected at that point and I had no idea what had happened with my grandfather. When I was really young I was told that my grandpa got sick and that’s how he died. I always assumed it was something like pneumonia or cancer like my grandma and I didn’t question it. Then when I got a little older I was told a lot about my grandfather and his service in the military. The family talked a lot about what happened in Guam and how my grandfather earned the Navy Cross.

“Richard joined the military when he was still in high school. On the exact day that others in his class were attending graduation, he was shipping out for basic training. He chose to enlist in the Army because he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps. He shipped out to Vietnam immediately. He served three tours before being honorably discharged due to his related medical conditions. He received many medals, including 6 Purple Heart Awards. He came home to Price, Utah, married and started a family.

“Richard would leave for a week or two at a time to go on trips across the United States on behalf of the Purple Heart Association. He always said that he needed to go help other veterans get what the government owed them.”

*****

“As a teen, I remember asking about my grandpa because no one ever talked about him. I wanted to know more. Finally they said that my grandpa had been diagnosed with Survivor’s Guilt. That he was guilty of surviving in Guam when seven other men didn’t. Men that had loved ones at home.

“He had even more guilt eating away at him because he survived and Corporal Buel W. Bray didn’t. He only made it home because of the sacrifice that Corporal Bray made. At the time my grandfather committed his crimes, the Veterans Affairs Department wasn’t established yet and there was no central place for veterans to receive care. Finally I learned that grandfather died because he killed himself due to not being able to handle all the guilt anymore. She said that’s what my family meant when they said grandpa, “got sick.” They weren’t referring to cancer or a lung infection. They were referring to the mental illnesses that our government sends its troops home with. This is why it’s always been so important to Richard to serve veterans themselves. He travels and helps them get their FULL benefits and to appeal negative decisions that the government has made that affect them.

“When I was about 20 years old, I was home alone at night. I was on my phone messing around and Googling my dad because I knew that there was an article somewhere about my dad when he worked in the mines and I wanted to see if I could find it. Somehow I ended up typing in my grandpa’s name. Immediately an article was pulled up that claimed my grandfather was a murderer. That he committed these atrocities in cold blood. That my grandfather was an absolute monster.

“I remember being totally shocked and not knowing what to do with myself. I hurried and stood up and said that my friend needed me, her parents were going through a messy divorce at the time, and I needed to leave. He told me to be careful and to invite my friend to stay at my house for a few days. I took my car and left. I sat in my car at the park down the street from my house and read everything I could about my grandpa and what he did. I bawled my eyes out and I had no idea what to do with what I had just learned.

“My mom asked her father what he knew and could only say that it was sudden and shattered the Aragon family. That everyone talked highly of my Grandpa Able and it shocked everyone when they heard it was him.

“But from what he has said to me, it seems more likely that my Grandpa Able was suffering from Survivor’s Guilt and PTSD; he was struggling to provide for his family, and he spiraled into a bad place mentally. I’ve asked relatives about what they remember of my grandpa and they tell me that my grandpa used to make pancakes and put cinnamon in them… That a few months before the crimes, there was a fair in Emery County that my grandpa took them all to and won a little box turtle at one of the booths and gave it to my dad and they named him George. We still had George until 2012 when he finally died.

“He remembers my grandpa making them warm tortillas every morning and putting butter on it, that they’d eat that while walking to school. I’ve asked if grandpa ever had a short temper or if he had moments where he would get really mad. No one remembers my grandpa ever being mean or short-tempered.

“But they do recall Abel and Eva worrying a lot about money and their dad leaving sometimes to go look for more work. This is part of why I really don’t believe my grandpa had Intermittent Explosive Disorder. I think what is much more likely is that he was suffering from his PTSD and Survivor’s Guilt. I have seen the medical records to prove that he was officially diagnosed with both of these. However, he was never able to get help for either of them and he was left completely untreated. I think the stress of needing to provide for a young wife and 5 small children was building and extremely daunting.

“He was unable to find steady work that he could do with his hip injury. As you may know, even now, the only real work in Price is in the mines. It’s dangerous work and it isn’t for someone with body issues. And if you are able-bodied, the work will destroy your body itself. I think that his Survivor’s Guilt, PTSD, and the stress at home, are what led to the incidents of July 4th, 1961. I understand how it can seem like there must have been something else that led to this explosive episode, but until you live with someone who suffers from these exact diseases and you see yourself how they affect every facet of your life, I don’t think you can truly understand how they can affect someone. Other members of my family who served in the military suffered from these same diseases and I’ve seen how it has almost killed them. Luckily, it’s now possible to fight for treatment from the VA and the positive results have been amazing. I also see how it would have affected my grandfather and so I think these two things, that were clinically diagnosed, but never treated, led to that terrible night.”

CHONITO RIDGE.. GUAM. MARIANA ISLANDS. JULY 22, 1944

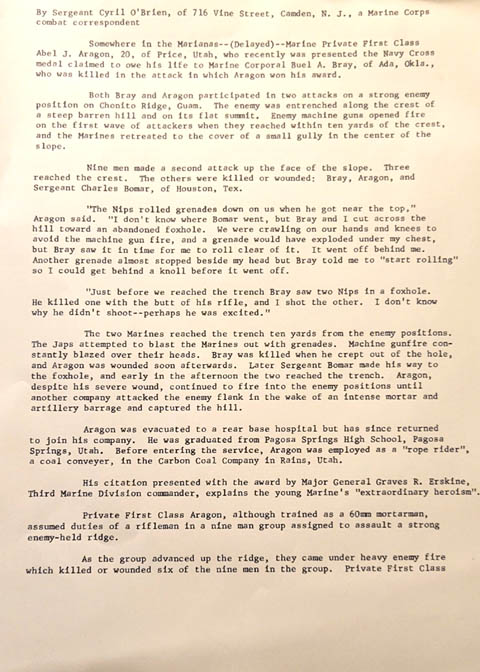

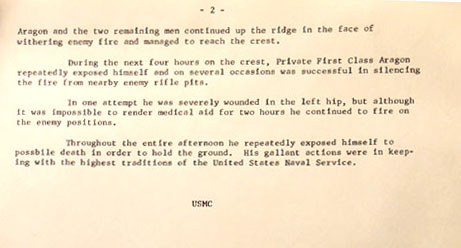

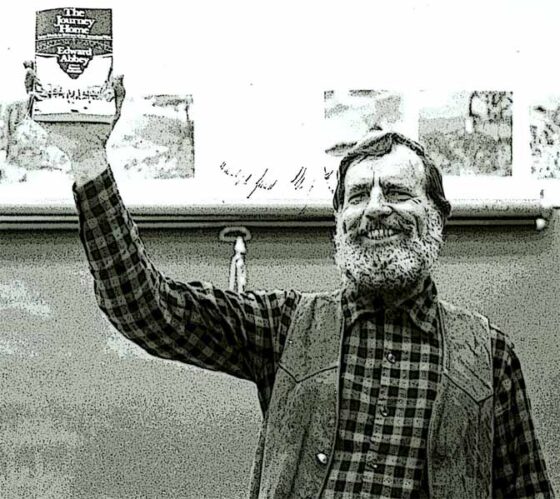

In the original story I wrote about the July 4, 1961 incident, I referred to Aragon’s heroism in World War II, and that he received the Navy Cross for his bravery. But this recent exchange with the granddaughter, in addition to sending me the photos you see in this story, she sent me a combat correspondent’s report, describing in much greater detail, the events of July 22, 1944.

After reading this, I had to wonder how anyone could return to a normal civilian life and resume his daily routines without some form of mental health assistance. But as the Aragon granddaughter notes, such services didn’t even exist at the time. Here is the greater part of that dispatch, sent by Marine Corps combat correspondent Sergeant Cyril O’Brien of Camden, New Jersey filed this report:

Somewhere in the Marianas—(delayed)– Marie Private First Class Abel J. Aragon, 20, of Price Utah, who was recently presented the Navy Cross medal claimed to owe his life to Marine Corporal Buel A. Bray, of Ada, Okla. who was killed in the attack in which Aragon won his award.

Both Bray and Aragon participated in two attacks on a strong enemy position on Chonito Ridge, Guam. The enemy was entrenched along the crest of a steep barren hill and on its flat summit. Enemy machine guns opened fire on the first wave of attackers when they reached within ten yards of the crest, and the Marine retreated to the cover of a small gully in the center of the slope.

Nine men made a second attack up the face of the slope. Three reached the crest. The others were killed or wounded: Bray, Aragon, and Sergeant Charles Bomar, of Houston, Tex.

“The Nips rolled grenades down on us when we got near the top,” Aragon said. “I don’t know where Bomar went, but Bray and I cut across the hill toward an abandoned foxhole We were crawling on our hands and knees to avoid the machine gun fire, and a grenade would have exploded under my chest, but Bray saw it in time for me to roll clear of it. It went off behind me. Another grenade almost stopped by my head but Bray told me to ‘start rolling,’ so I could get behind a small knoll before it went off.

“Just before we reached the trench, Bray saw two Nips in a foxhole. He killed one with the butt of his rifle, and I shot the other. I don’t know why he didn’t shoot— perhaps he was excited.”

“The two Marines reached the trench ten yards from the enemy positions. The Japs attempted to blast the Mariess out with grenades. Machine gun fire constantly blazed over their heads. Bray was killed when he crept out of the hole and Aragonwas wounded soon afterwards. Later Sergeant Bomar made his way to the foxhole, and early in the afternoon the two reached the trench. Aragon, despite severe wounds, continued to fire into the enemy positions until another company attacked the enemy flank in the wake of an intense mortar and artillery barrage and captured the hill.

“Aragon was evacuated to a rear base hospital; but has since returned to join his company…His citation presented with the award by Major General Graves R. Erskine, Third Marine Division commander, explains the young marine’s ‘extraordinary heroism.’”

In an addendum the reporter added:

“Private First Class Aragon, although trained as a 60 mm mortarman, assumed duties of a rifleman in a nine man assault to a strong enemy-held ridge. As the group advanced up the ridge, they came under heavy fire which killed or wounded six of the nine men in the group…During the next four hours on the crest, Aragon repeatedly exposed himself and on several occasions was successful in silencing the fire from nearby enemy rifle pits….In one attempt he was severely wounded in the left hip, but although it was impossible to render medical aid for two hours he continued to fire on the enemy position….throughout the entire afternoon he repeatedly exposed himself to possible death in order to hold the ground. His gallant actions were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

USMC

(For more on award-winning war correspondent Cyril O’Brien, click here.)

More than anything, it’s important to note that after that brutal ordeal, Aragon could probably have requested to be transferred stateside, and end his active participation in the war. But instead, despite the severe hip injury, he returned to his unit and continued to play an active combat role in the war.

The war in the Pacific ended in August 1945. He returned home that December, married Eva and started a family. Abel returned to the only kind of work he knew as a coal miner. But from the day he returned to work, he endured the pain from his war time service. No doubt he also tried to deal, on his own, the effect the war had on his mind. As I noted earlier, Aragon’s granddaughter took issue with my suggestion that Aragon suffered from Intermittent Explosive Disorder. Recently she wrote to me:

“I hope that I’ve been able to portray that I honestly believe that it was PTSD that led to what happened and not an intermittent explosive disorder. My grandfather was never known to have a short temper or to have explosive moments, even in the privacy of his own home. I think after reading that letter from Sergeant Cyril O’Brien, it’s clear that he had PTSD that wasn’t managed in any way and he had all that pressure building around him, only making his PTSD worse.

“As you said, PTSD wasn’t even formally recognized at the time, let alone treated. I think that it would be a good idea to point that out as well and maybe word it as a call to arms? Our country has a long road to go down if it is ever going to truly recognize what war does to our country’s veterans and if they want to *truly* treat our veterans’ PTSD diagnoses. Not that I want it to seem like an excuse though, of course, because it absolutely is not an excuse for his actions. It’s just an insight into what was going on in his mind.”

The Aragon granddaughter also noted her uncles’ service in Vietnam. She believes that they served in part to make up for the actions of their father. It’s difficult to imagine how they dealt with the conflicted feelings they must have had for him. For years, they had only heard of the war and his extraordinary heroism. Then, in one insane moment, every bit of their father’s honor was stripped away by so many members of the community. The granddaughter wrote:

“As far as the children’s service in Vietnam, I believe that their service was very much a way for them to make up for their fathers’ actions. I also think that because of how young the children were when their father died, the main thing that they remember was that he did serve in the military himself. My family has mentioned multiple times that a lot of their memories of their father include mentions of Abel’s service. Whether it was Abel’s friends talking about his service, or Abel having a hard time finding work because of his disability from his service.

“Most of the memories are peppered in some way with the fact that their dad was in the service himself. So when the kids became old enough to be in the military themselves, they felt compelled to serve as a way to be closer to the memory of their father, as well as a way to make up for their fathers’ actions and to vindicate the Aragon family.”

THE PHYSICAL INJURIES AND THE FATE OF DENNISE

Finally there is the role that Abel Aragon’s physical injuries may have played in the theories about Dennise Sullivan’s disappearance. I’ve discussed at length in previous installments of this story about the presumed kidnapping of Dennise. It’s the only reason the FBI led the investigation. But I remembered and reported an observation that Moab locals Cliff and Wilma Aldridge made on the afternoon of that fatal July 4. They had traveled out to Dead Horse Point that afternoon and saw Aragon, though they had no idea who he was. But Wilma, for some reason, noticed his shoes. “They were worn out at the heel and he seemed to limp.” She recalled that “he looked to be in pain.”

It’s why I made a point of asking the granddaughter if Abel had physical problems with his feet. It’s then that I learned from her of the hip wound from Chonito Ridge. Here is what she said:

“As you read, he sustained injuries to his left hip which caused him to have a limp. He was very disabled because of his hip. My dad was only 10 at the time but he remembers that his dad couldn’t walk very well and he was constantly turned down from work because of his hip issues. The coal mines in Carbon County were willing to hire almost anyone because they needed workers but my grandfather couldn’t get any type of job there. He also couldn’t work in offices because he wasn’t able to sit for long periods of time behind a desk. But then on the flip side, he wasn’t able to do any hard manual labor either. As far as my dad knows, Abel was only working for locals that would be willing to pay him for whatever odd jobs he could do for them.”

“I honestly don’t think he could get ahold of Dennise and kidnap her. I don’t think he had the strength and even if he did, he wouldn’t have been able to keep his strength up and the pain at bay for long. He wouldn’t have been able to keep ahold of her and she would be able to find so many chances to escape from him. Of course, I’ve never been kidnapped though and I know the shock that she would be in, and I never want to come across as someone who would victim blame her.”

The fact that he was so disabled does lend more credence to the idea that Dennise could have escaped from the VW before Abel could catch up with her. And with Leonard Brown just seconds away, Aragon may have felt that his only option was to leave. Did Dennise run blindly and frantically into the darkness and meet her end at a 100 foot vertical cliff? Did she somehow survive the fall but lived briefly in the 100 degree heat? It’s doubtful anyone could survive a fall from that height.

Charles Boothroyd had mentioned, just a week after the shooting, that he hoped Dennise met a “quick and merciful death.” As I’ve noted before, there is no happy ending to this story. But the family of Dennise would prefer that kind of ending to the torturous and prolonged fate that many feared.

And it matters to the Aragon family too. The story his granddaughter has told does not portray a man who could take a 15 year old girl hostage, terrorize her for hours or days, and then kill her in cold blood. Nothing in Abel Aragon ever suggested that kind of personality. Once that violent moment passed, it’s difficult to imagine he could maintain that murderous state of mind, especially with a girl who was exactly the same age as his own daughter. As the family noted, and I conceded, my suggestion that Abel Aragon suffered from “intermittent explosive disorder” was wrong. He was not a man who lost his temper. And he wasn’t a pathological killer—Abel Aragon was not Ted Bundy. He was certainly depressed and both he and Eva worried about their financial future. But he wasn’t by nature a violent man.

Whatever happened on July 4, 1961 was something no one will ever fully understand. But the story is much more complicated than many people realize. Perhaps it’s important to remember once more what Dennise Sullivan’s grandmother Grace, told Jeanne, so many decades ago…

“There are two sides to every tragedy, that we need to show compassion even in our own suffering.” For Jeanne, her grandmother’s words were comforting and brought her peace; it was easier to live with the loss of her mother and sister. Years later, Jeanne recalled, “because of that, we never hated Abel Aragon for what he did.”

I hope the Aragon family has been able to find peace. They certainly paid a heavy price as well for the terrible night of July 4, 1961.

*****

Jim Stiles is the founding publisher and editor of The Zephyr. He can be reached via Messenger or at cczephyr@gmail.com

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

BE SURE TO LOOK IN THE PROMOTIONS FOLDER…Gmail INSISTS!!!

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our amazing historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

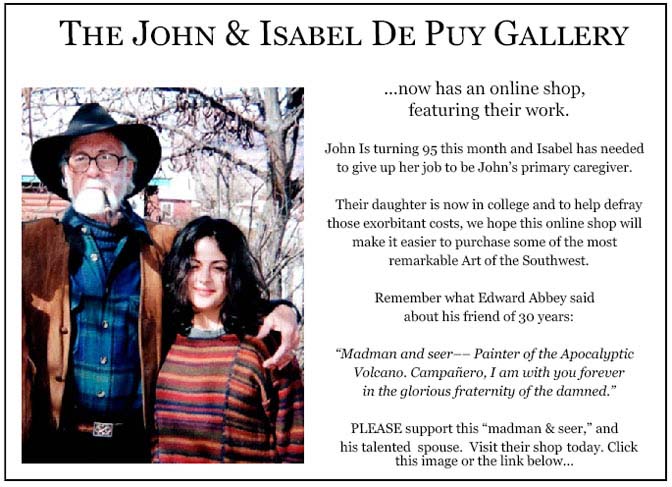

Six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned. ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

https://rangemagazine.com/subscribe/index.htm

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

Thank you for pursuing this story. I’m certain that many of the tragic headlines we read every day have ongoing repercussions that are never known by those who read the original reports.

Jim, this series of stories is definitely a powerful thing. Well done. I suspect there is yet a bit more to come because I can’t see you just dropping it while knowing there are still more files sitting in the National Archives. A great piece of journalism.

You’re right. There’s a specific file series that I hope to pursue. I’m hoping Ms Calgano of the NARA might be willing to examine that file but limit my request to information regarding blood samples and fingerprints. I think the information provided by Aragons granddaughter regarding his disabilities makes an even stronger case that he might not have caught her. It’s true that people can freeze in a moment like that, but her instincts for self preservation were obvious when she tried to get away in the VW.

Thank you Jim for another well written update on this story that has haunted me for decades since I learned of it as a small child growing up in Moab, Utah. I am heartbroken that some of the people in Price, Utah did not have it in their hearts to act with compassion toward the family of Abel Aragon who are the other victims of his unfortunate actions. It seems ironic (and speaks to the character) of Jeanne and her grandmother, that they were so concerned for them. Hoping that time can heal these wounds and that all three families (the Boothroyds included) can feel feel a greater sense of closure. Of course, without finding the body, or knowing of the whereabouts of Dennise, we can get no closure.

Another over-the-top story. I am so happy that Abel’s granddaughter’s e-mail made it to you. The Aragon family went through their own torment and I am sad to hear of what they endured. I hope that Abel’s family is able to find some peace if they read this article.

Jim, your impeccable writing deserves a major award. I was very glad to read your article this morning and have more details about the family.

Thanks Kay. But I’m afraid the MSM doesn’t even acknowledge the Zephyr exists, much less that it has value. A reporter for Utah Public Radio once told me I “wasn’t a real journalist.” I had asked him why no publication in Utah had covered the Zephyr’s defamation/ first amendment lawsuit.

I couldn’t stop reading this article once I began. An amazing write-up, Jim, and I hope more information comes to light from the FBI files when those get delivered.

Thank you thank you very much. We have tried all these years to let Ables family know we prayed and thought if them all these years. Ive tried to get reporters to tell them of our compassion, but now you finally have given me the peace in my heart by letting them know through this article. I am pleased to hear their story. God bless.

Jeanne. Fantastic response you sent to Jim. I’m so happy that you can put that part to rest. I’m sure your Dear Grandmother is resting better now. I am thrilled that we connected last year

Thank you Jim. This is a wonderful heart wrenching story. For all parties. And to Jeanne thank you for responding to Jim’s article. I’m so happy you are that special lady you are. Forgiving is huge. I’m hoping the Aragon family finds peace knowing that neither family holds I’ll feelings. It breaks my heart to learn what The Aragon children had to live with.

The granddaughter did a fantastic job at her story. I hope she knows that the Boothroyd sisters do not blame anyone. I hope she reads all the comments especially Jeanne’s.

Your first article is what brought Linda, Jeanne and I together again after many years. I feel like your new addition to the story will give Jeanne peace in know ahead and her Grandmother never held a grudge

Thank you all for your wonderful comments. So glad we found you Jim

You’re absolutely correct in that observation. I had thought the same thing but hated to have someone take it the wrong way. But yes a black and Hispanic were not friends.

These revelations are stunning. The email from Aragon’s grandson is poignant beyond words. The historical “twists” you have revealed through your research leave one bewildered. The narrative changes from a public mystery to a tragedy, followed by many unseen and painful tragedies. It’s hard to wrap my head around this in one reading. I will read it again tomorrow with the same dread and sadness that now encompasses me.

Jim, your reporting on this story deserves recognition. You have acquired so much additional information and if this case is solved as to the whereabouts of Dennise, you will be the one to do it. I feel blessed that my sister and I have been reconnected with Jeanne and that Abel’s granddaughter was able to connect with you to offer her insight into this story. I am sad that Abel’s family had a difficult time and still continues to be haunted by this mystery.

I loved looking through the replies above and getting a sense of the inter-generational narrative and grace that has followed this story over the last 62 years.

While not in the same ballpark as ‘forgiveness’ – everyone at this point is well removed from the actual event – the information and history resulting in a ‘suspension of judgement’ is remarkable. Often the more we learn about a one off crime like this contextualizes it in a much more nuanced way than could have been possible at the time, and while it didn’t lead to the hoped-for location of Dennise perhaps it led haltingly to a better result along the way.

Somehow it called to mind Hal Holbrook’s line to Emile Hirsch as Chris McCandless in Into the Wild.

“When you forgive, you love. And when you love, God’s light shines on you.”

https://youtu.be/HkywD5wABwI

Apparently that exceeded the grasp of the folks in Price at the time. Maybe that’s the lesson to be learned.

Keep probing at NARA, Jim. I have no idea what privacy or national security issues compel them to restrict access to what remains, but perhaps there’s more to be uncovered. It’s not as if the gracious remaining family members have anything to shield (that I can imagine), or that we’d somehow have a lower opinion of the conduct of the investigation. We’re way past that.

Thanks for the update!