INTRODUCTION

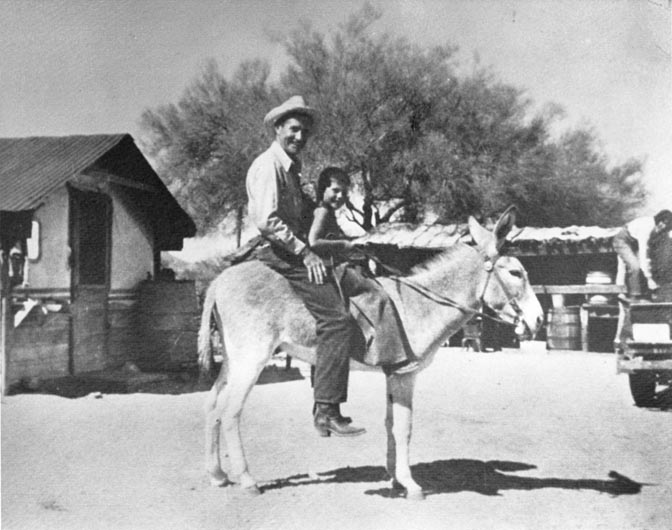

Alan “Tug” Wilson isn’t exactly a household name to most Zephyr readers. But it should be. While he may not be instantly recognizable, many lovers of Canyonlands and Arches National Parks will recognize his father. Tug was blessed to be the only son of Bates Wilson. In 1949, Bates became the first official superintendent of “The Arches,” when it was still a national monument. Just a year after his arrival, Bates was introduced to the vast untouched landscape to the west of Moab— and north and south of the little town as well. The canyon Country of southeast Utah was still an almost untouched landscape, known only to the ranchers and cowboys of Scorup/Sommerville Ranch, and a handful of intrepid explorers. The land lay empty for centuries. But I can still remember, when I first moved to Utah, and the frequent reminder to some of Moab’s newer residents, that southeast Utah had a larger human population a thousand years ago than it did in the 1980s. The evidence of that civilization was still everywhere in 1950.

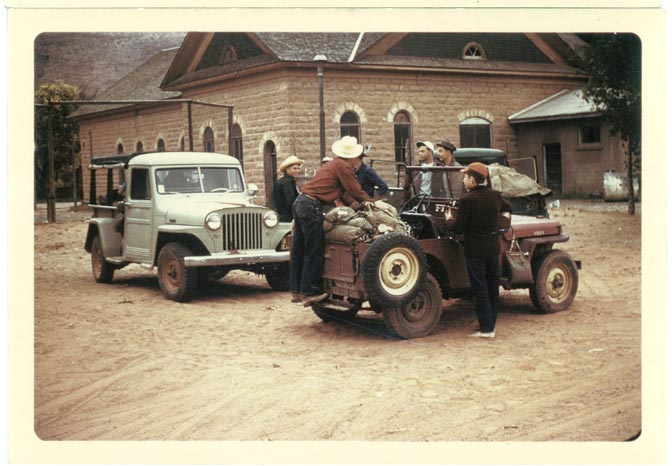

Few realize that it was Tug’s interest in what was then called “the most remote area of the continental United States,” that first lit his fathers interest. Later the canyonlands became Bates’ obsession. Within a year of the Wilsons’ arrival, Tug had purchased a used 1946 CJ Jeep to extend his explorations. It was that jeep and Tug’s enthusiasm that inspired Bates to go take a look.

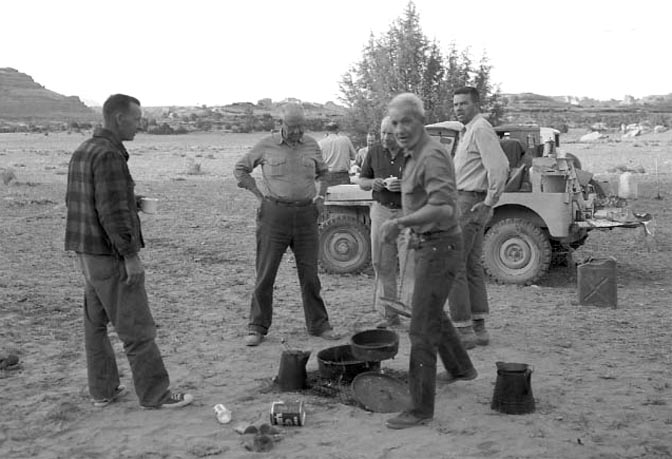

The rest is history, though there may be much of that history that few realize. Thanks to Bates’ “Dutch Oven Diplomacy,” Canyonlands became a 1964, after a fifteen year campaign by Bates to make it so. Fifty years later, Tug spoke at the 50th anniversary of the park. Below is Tug’s speech to those who gathered at the Needles District to celebrate the occasion.

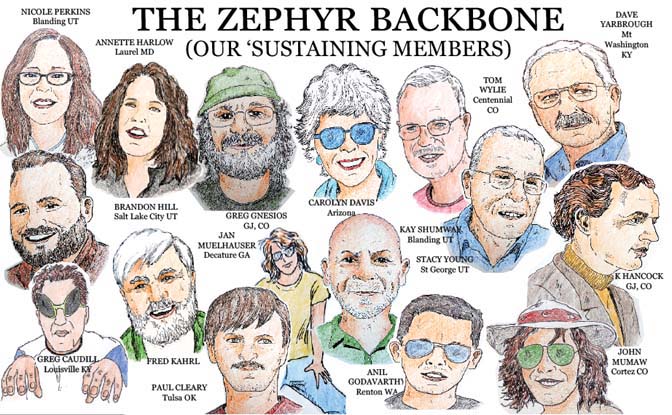

Though I had recognized Tug’s name and his enviable role as Bates Wilson’t son, I had never met him and knew little of Tug’s own personal history. Then, about three years ago, I received a Zephyr Backbone contribution from “Alan Wilson.” I realized it was Tug and since then, we have corresponded regularly. Though we still haven’t met , I consider him a friend. I’d also have to admit that after I learned more about Tug and his life, I have been green with envy. What an amazing life story.

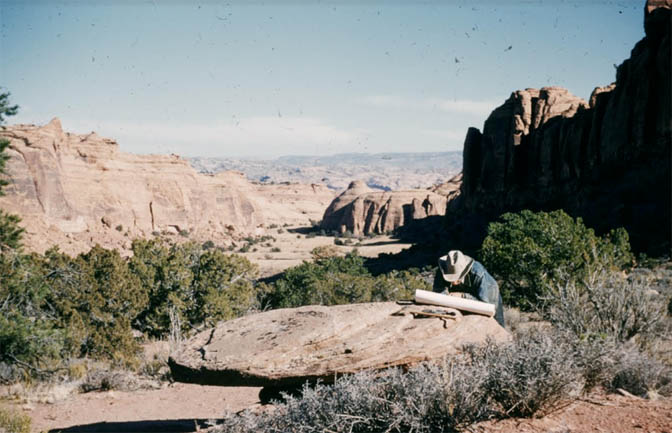

But it is Tug’s to tell. Below is the speech Tug gave in 2014. But in addition, Tug started sending me photographs, brilliant Kodachrome transparencies of that special time in his life. Now, I’m happy to share them with Zephyr readers.

Finally, this is the first of several stories by Tug that I will be honored to share in the future. In addition, the images you see in this post are just the beginning. Looking at tug’s photos and hearing his stories reminds me why I have been “hopelessly clinging to the past,” to a time so different from the world of 2024.

Jim Stiles

REMARKS BY ALAN ‘TUG’ WILSON on the 50th ANNIVERSARY of CANYONLANDS NATIONAL PARK’S CREATION:

September 12, 2014 at the NEEDLES DISTRICT

When It Began and Where:

On a cold, mid-March day in 1950, my father, Bates Wilson, his cousin, Bob Dechert, a Philadelphia Lawyer, Ross Musselman, a local outfitter, two horse wranglers and I — then 13 going on 14 — started on a ride with several pack mules from Dugout Ranch in Indian Creek Canyon. We were about to spend a few days in one of the last truly remote sections of the American West, an area called the Needles.

On the second day, we arrived and camped for about four or five nights on the slick rock ledges overlooking Squaw Springs. With a magnificent view of Wooden Shoe Arch, Squaw Butte, and the Nubbins in the foreground, where the Anasazi chipped arrowheads, there could not have been a better place for Bates to get a grasp of this largely untouched and awesome place.

My family had been at Arches less than a year and in some ways we were trapped in the narrow valley north of Moab and the Colorado River. The Rock House ranger residence at Arches headquarters had limited views. Here at Squaw Spring one had a 360-degree view to scan the landscape to the heart’s content. It was very different from Arches. It was GRAND.

Bates got the idea that this was the “Land in Between” — between Arches and Natural Bridges National Monuments, for which he was also responsible. This was all new country to Bates, but he wondered, if Arches and Natural Bridges qualified as national monuments, why didn’t this? It was spectacular.

From Squaw Springs camp, we rode to the Confluence and gazed into the chasm created by the Green and Colorado Rivers, as they merge and head into Cataract Canyon. From that high vantage point, our eyes landed on the Maze. In 1869, John Wesley Powell had climbed out of the canyon and looked across the rivers to the opposite rim, to the very spot we were now standing. On the ride we could make out distant panoramas of Junction Butte, Dead Horse Point and Grandview Point.

On our return from the Confluence, we discovered that Ross had not fully closed the Dutch Oven lid that had been slow cooking over juniper coals for hours. Consequently, Nature added an extra ingredient to our supper of Pinto beans and pork…sand!

Several days were spent exploring the Grabens, and probably Chesler Park although I do not recall how much time we spent there. Eventually, we broke our Squaw base camp and headed up Salt Creek. Around Cave Springs, I spotted what I thought was a set of Jeep tracks in the sand. Those would prove very useful because they gave us the impetus to return, over and over again, to assist Bates in his enthusiastic exploration of this new area.

I was able to help more than I even realized at the time. Not long after we returned home and Arches, I bought my first Jeep, a used 1946 CJ 2A.

But on our first visit, the ride up Salt Creek was long and tiring. We must have camped midway. We saw ancient ruins, some rock art and a good many arches, as well as our first view of Kirk’s cabin.

On the last night of this first trip of exploration, we camped in the Meadows of Upper Salt Creek. Overnight, it snowed more than nine inches, and on the morning of my 14th birthday, I awoke to a wet saddle and soaked, cold boots.

After a no food breakfast (we had been out of food for a couple of days), Dad found the old Bull Trail out of the Meadows. We arrived under Cathedral Butte, expecting a truck and driver to be waiting for us. The plan was for the driver to haul us, and the stock, back to Dugout Ranch. But with 20+ inches of snow at 7500 feet and above, there would be no truck.

So, practically running on empty, we made the very long ride down Cottonwood Canyon. We were cold, hungry, and wet, back to Dugout. But that cold ordeal did not deter Dad from thinking ahead to the next exploration. Back home at Arches, my mother Edie had a big meal of roast beef, potatoes and blueberry pie with a butter-rum-laden hard sauce topping.

It hit the spot.

*****

We returned many, many times to explore Lavender, Davis, and Horse Canyons, Salt Creek, Chesler, the Grabens. We used the Jeeps and the assistance of Boy Scouts for explorations and to document our finds: Bates was hooked!

Those first few nights at Squaw offered us magnificent sunsets and sparkling sunrises. They made a lasting impression on my dad. Later, if we did not camp on the slick rock ledges because it was just too hot, we would camp under the rocks and amongst the trees. It was one of Bates’ treasured locations and now the site of the Squaw Flat campground’s “A” Loop.: Visitors today get the same views we did in 1950.

After our first pack trip with an outfitter, Bates decided that from now on, he would handle the food and other plans for any future trips. He decided it was not the best idea to delegate too many responsibilities to others. It was too risky and you go hungry!

Many people have asked me over the years, ‘what was it like when we first came here?’

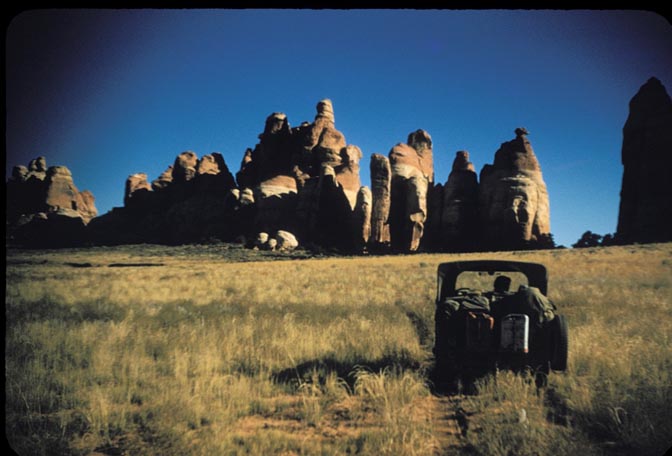

First of all…there was NO Road! The road, if you can call it that, from highway 160 (now 191) was all dirt and treacherous, once it descended to Indian Creek, and further, to Dugout Ranch. It was what we’d call “a grandma gear pick-up road.” To keep our forward momentum, we had to “bounce” our way up the ledges, and through the sand pits. There was no road whatsoever beyond Dugout Ranch. From there, all we had to follow was a horse trail to where we are today, with a tricky crossing of Salt Creek. But once here, it was: Dead Quiet.

The air was crystal clear! As clear as I could ever imagine it. No haze. No dust. Just deep blue skies, punctuated by brilliant, bright Kodachome clouds.

And NO PEOPLE.

In the first 10 years of exploring what would become Canyonlands National Park, we encountered a total of five people: We encountered one party of two in 1952; Dad gave them directions to find what later became known as Angel Arch, the icon of Canyonlands. Once, in 1953, we came across a lonesome cowboy, on his way from the West fork of Salt Creek to Cave Springs. And finally, in the fall of 1958, we met up with Kent and Fern Frost. They were in their green jeep, in Horse Canyon, checking out the area for future tours. But that was it…. FIVE.

But most impressive of all was the NIGHT SKY: Absolutely ‘dead dark,’ except for the Milky Way and other major stars. There were zillions of them. After those nights, Bates always wanted this to be a “Dark Park,” and he would show it off to all those who camped with him.

*****

Moab was a sleepy, mostly Mormon town, with gravel and dirt roads in and out. For electricity, Moab was OFF GRID — a local hydro plant and small diesel generator produced what power was needed. And there was limited water, and a single Cu wire telephone line; it was often strung on Coke bottles, perched on dead Juniper limbs.

It’s hard to believe today, but IF a visitor happened to find Moab in 1950, and ask at, Robertsons’ gas station, for example, “What is Arches About?” the response would most likely be, “Oh nothing but rocks with holes in them.”

If a phone call came in for Bates, God forbid from Washington, and he was not at the Arches Office, the operator would likely tell the caller, “Oh, I think he just left the Arches Café and went to Millers… I will ring them and get you on the line. It was a small town and everybody knew Bates and his travels. He was usually found.

And imagine, back then… No Facebook. No Twitter. No WiFi. No nothing. Just a beautiful and serene unknown part of the American southwest.

*****

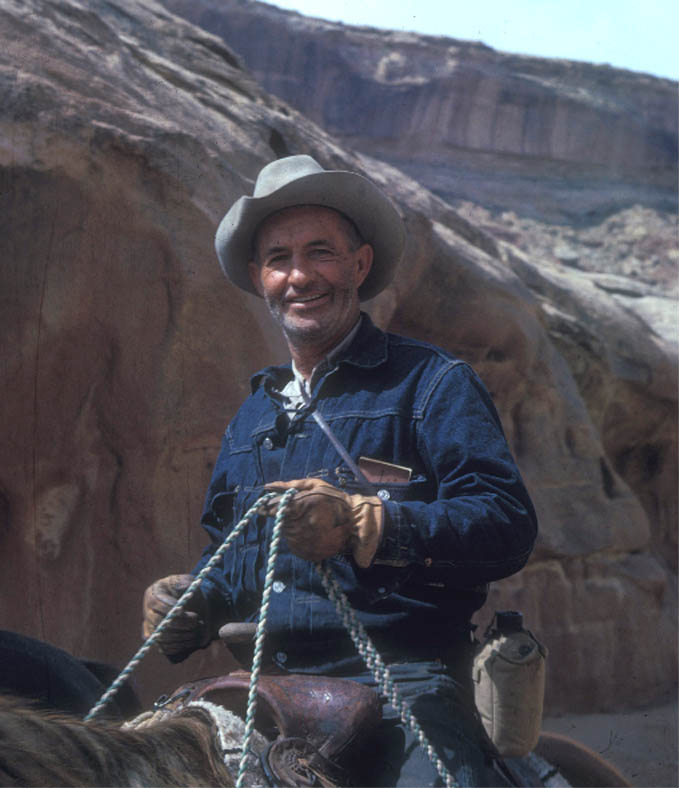

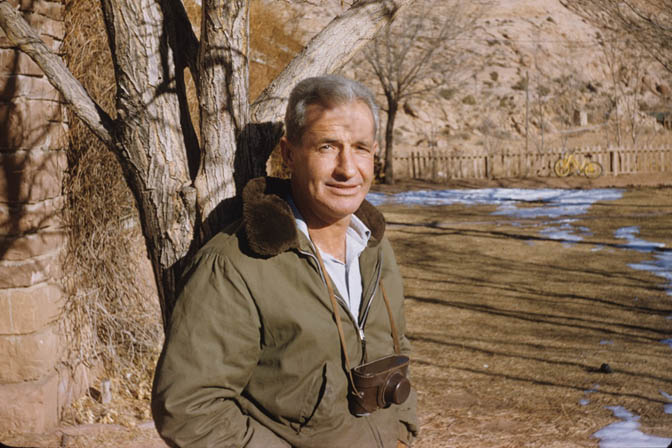

There’s always another question that everyone who loves this park likes to ask me: ‘What was Bates Like?’

He was a good father to me, allowing me to do largely what I wanted, and to pursue my interests. He often allowed me to take a lot of risks. We had many wonderful exploration trips together and shared a lot of unusual experiences.

Dad was affable, and made friends easily. He treated his staff, as limited as it was, with great respect, and often worked hand-in-hand with them doing the chores, or building trail. No job was beneath him, as he ran a small National Park Service site. He wanted ALL visitors to have a good experience in the Monument, to see something special, to be safe, to learn. He was discreet most of the time. But not always.

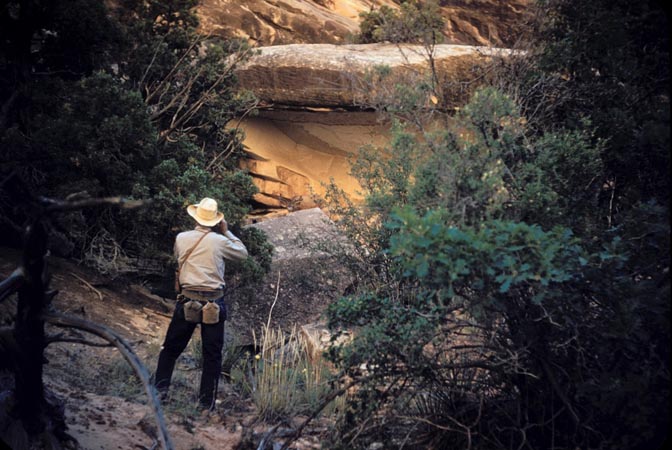

Bates did not like office work, and was often “out in the field.” Meetings were seldom held in an office; rather than the office he could be found outside somewhere, showing off something…a new arch. A new archaeological discovery. Cowboy artifacts. Bates’ preference was to see it first hand. He had little use for black boards or paper.

He had a keen eye for alignment of roads, trails, camping/picnic areas such as here at Squaw Park. Somehow Bates could spot a previously unknown ruin on a cliff before anybody else. He could hike all day long and then make camp dinner with ease. As they planned the park’s future and the inevitability of paved roads, he liked to site and plan turnouts where visitors got good views…and many of them.

And Bates Wilson was a very handsome guy, movie-star like, and very likable. His greatest gift though, may have been his sense of humor.

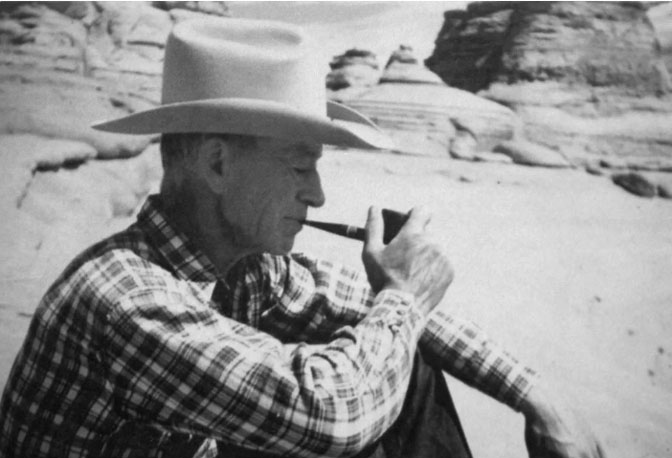

My dad never had many things — he was a practicing minimalist. He carried a surplus 1 quart canteen, maybe a biscuit, and a climbing rope. He owned a Savage 30-30 saddle gun, which was often with him. There was his saddle, cowboy and “desert” boots from Millers, with a soft white foam rubber sole, excellent for rock work, and several well-worn Stetsons. He did have NPS “Greens” but rarely wore them. He preferred Levis, an NPS gray shirt, and one of his hats or caps. He had a couple of Levi Jackets, some better than others, that he wore during the cold weather. You would find him with a pair of Buckskin gloves tucked into his back pocket. And he always carried a Kabar pocket knife.

We camped using a cowboy bedroll: a tarp, a used surplus Navy air mattress and a surplus sleeping bag. No tent. We never slept in a tent.

Cooking was done over oak or petrified Juniper coals in two Dutch ovens: one shallow one for biscuits, and the other for one-pot meals of meat, tomatoes and potatoes or beans and onions. In the mornings, we would use the shallow biscuit Dutch oven for bacon and eggs. In the Jeep, we always carried an axe, a shovel, generally five gallons of water and an extra five gallons of gas. That was it.

We would travel by Jeep to a good camping spot, set up a quick camp, have dinner, then “poke” around in the glow of another magnificent sunset. He was always searching for more — we’d go as far as the Jeeps could take us safely, then hike to the next canyon or ridge or ruin. We never wasted a moment…we were always up before sunrise, and to bed shortly after sunset and darkness moved in.

*****

Community was important and Arches was the first NPS location we had lived in that had any sort of real community. Bates jumped at that opportunity feet first. Overnight he became the March of Dimes chairman during our first fall in Moab. A couple of years later, Bates was chair of the rodeo. He was also very active in the Lions Club, the Boy and Girl Scouts — he made many long lasting friendships in Moab.

My dad got along well with the ranchers, and could and did ride with them to check on stray cattle inside the boundaries. One moment he would be riding the range, and later in the day, taking a potential movie director on a “sites” tour.

He also got along with the extraction people listening to what concerned them and letting them know what concerned him. He was patient.

If you came to be interviewed for a position at Arches, it was pretty likely you would be walking trails with him, or a boundary line, or perhaps an overnight to check something out…he was looking to see if a new ranger was practical, and had good common sense. He wanted to know if they would and could clean a privy if needed, or get un-stuck from quicksand.

He wanted a crew that could be relied on when needed.

Bates learned from all the folks who came to Arches and Bridges, and later Canyonlands…he was a sponge for information, and later would squeeze it out so he could pass the knowledge he had gained to others. And he was eager to learn from everyone, whether from experts or just plain Mr. and Mrs. Joe Visitor.

Often, he over-committed himself, and as the possibility grew for Canyonlands to become a park, Canyonlands became his main priority, even over family. His family life connections suffered as a result.

However, it might just be that Bates is the one and only National Park Service person who could have orchestrated the creation of a new national park out of lands he was not responsible for. It’s a legacy question to be researched.

*****

Today I was also asked what has been named for my father, Bates Wilson. Let me digress a bit and give some insight on his view of naming things.

Dad thought nothing should be named for a person or family, but rather after what it looked like, or maybe some incident pertaining to its discovery: Druid Arch looks like Stonehenge, Angel Arch an angel, Big Ruin is a big ruin, Five Faces, Devils Pocket.

So what is named after him? Not long after he passed on, Sandy Holloway, his long time assistant called me and asked that question. We came to the conclusion that he would go along with the naming of a campsite after him, since it was, in part, his “Dutch oven diplomacy,” and his memorable camp outs, where decisions were best made. So we named the campsite at the mouth of Angel Arch Canyon after him. That site was shut down when the Salt Creek road was closed, years ago, and now the new Bates Wilson site is on the road to the Confluence. He was modest and never sought fame for himself or family.

*****

Finally, Bates Wilson’s long quest for a “Canyonlands National Park” turned out to be 15-20 year endeavor But without his unshakable commitment, we most likely would NOT be celebrating 50 years of Canyonlands. We owe much of this awesome landscape’s preservation and the treasures it holds, to my dad. He passed on to his children and grandchildren a love and respect of the outdoors and park lands, and he inspired them to explore as much as their limitations would allow them.

After my dad’s many years of work here at Canyonlands, I think he would be pleased with the fact that this park has remained Dark, and a Rugged one. It is now visited by many; the NPS tried to provide some kind of experience for all levels of capability to enjoy.

From rugged trips to the Maze, and hard to access locations via Jeeps in all districts, to the more accessible vistas at the Island in the Sky District of Canyonlands. He foresaw short to long hikes and more strenuous backpacks into the Needles. The hikes offered a mix of arches, canyons and Anazasi sites. And almost as a bonus, the challenging river expeditions.

I think my father would be pleased to see it today — a place where visitors can still enjoy the clear blue skies by day and zillions of stars at night. And where after a long day out exploring the park, people can still sit down and relax over a Dutch oven dinner, spiced with a dusting of sand!

*****

Alan “Tug” Wilson was born on March 31, 1936, during the Great Depression in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Bates and Edie Wilson. They were a so-called CCC/ NPS family (Civilian Conservation Corps/National park Service). As World War II came to America after Pearl Harbor, the Wilsons moved to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in southern Arizona. Soon after, Bates volunteered to join the war effort in the Pacific. He returned home, three and a half years later, and the family moved to El Morro National Monument in New Mexico. After a three year stint there, and with essentially no schooling for Tug, they moved to Moab Utah. Bates became the first superintendent at Arches and Natural Bridges National Monuments (previously the persons in charge had been called ‘custodians.’ And finally, Tug was able to attend school.

He was always interested in science and how things worked and why. At 13 in Moab, Tug started to learn the electrical trade; at the same time, he opened his own guide service (at age 14!), and introduced visitors to places that were not easy to get to or well known. Soon, that endeavor extended into the Needles area of what became Canyonlands — it was the real focus of his explorations.

After high school, Tug attended the University of Utah, to study electrical engineering. After graduation, he went to Cornell University in New York, for a graduate degree. In the fall of 1960 IBM Research hired him, straight out of Cornell, where he spent nearly 38 years doing research on failure modes of computer components and the physics of lithography, E-beam and X-ray for chipmaking.

From wandering the remote canyons and mesas of southeast to Utah to Cornell, to IBM. An amazing life. And perhaps best of all, Tug and his wife Maxene have been married for 63 years and have two wonderful grown adult “kids.” Together they have continued to explore and enjoy many years returning to his beloved Canyonlands. Of southeast Utah. Tug is now retired and lives in Boulder CO.

*****

TO COMMENT ON TUG WILSON’S STORY, OR IF YOU HAVE YOUR OWN MEMORIES OF ARCHES AND CANYONLANDS FROM THAT LONG AGO TIME, PLEASE SCROLL PAST THE ADS AND PROMOS TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS POST. THANKS…JS

*****

This is only the first installment by Tug. Look for more stories ands more incredible Kodachrome transparencies by Tug in the weeks to come, like — the discovery of Druid Arch, camping out before it became “glamping,” and maybe even how “Tug” got his name. Stay tuned…

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

$55 Each or Two for $100 (Free Shipping.)

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

WE WELCOME YOUR COMMENTS, ESPECIALLY IF YOU HAVE YOUR OWN MEMORIES OF CANYONLANDS, OR MOAB, OR SOUTHEAST UTAH, FROM THAT LONG AGO TIME.

You have the most interesting resources for stories! Tug, at 14, was already showing that his dad’s way of raising him had distinct advantages! How many kids nowadays at that age could actually become entrepreneurs? And his father’s tenacity is why those unsullied lands have been preserved to this day!What a wonderful look into the lives of father and son who actually DID something for preservation! Enjoyed it immensely!!

Thanks Donna. I’m happy The Zephyr could share Tug’s story. Like you said, it would be hard to find a 14 year old today with Tug’s work ethic. And to be honest, few boomers could measure up. But then we didn’t have Bates as a father.

Wow, the start of the Jeeps and Tourism in Moab, now days it’s way too many of both, but all so interesting.

Is this also the folks that Wilson Arch was named after south of town ?

I spend a lot of time around and in Chesler Park. It is always a revelation and a joy. And the stars still are impressive.

I have also camped many a night at Squaw Flats. And I owe a great deal of my love for Chesler and the Flats to the foresight and efforts of Bates and Tug. Thank you to both of them! I cannot wait to see more of Tug’s collection.

Now how long before the name of Squaw Flats gets changed? (As it should.) Anyone want to place bets?

Thanks for sharing the story of your dad and your family. My mothers side of my family settled in Hanksville pre 1900. I’ve always enjoyed the stories and history of southern Utah. Your recollections along with the work that your father accomplished certainly add to all of the areas history.

Thanks to you both for sharing this with us all. What a great place and time to be a teenager!

Tim Steckline. Good to hear from you. Among Tug’s stories is the discovery of Druid Arch. Imagine that. Druid was unknown in 1950.

Great photos.

This is a wonderful chronicle and a great, fun read. Thank you, Tug!

My first trip through the Needles was in September of 1985. When I drove to the top of “one way hill” there were 2 hikers standing in over a foot of fresh snow. I said hi but they just stared like I was an alien. I drove on to cathedral Butte and down to Dugout ranch breaking trail the whole way. The snow was deep, maybe 18″ in spots. Lucky it was fresh powder and I didn’t have much trouble. I got home about 1 am to a “not happy” wife.

great story and photos–love it. When you come to Boulder to (finally) visit Tug, remember you’ve got a place to stay if you need it.

Thanks Evan. I’ll keep in touch. After all these years, it would be great to reminisce face to face.

How interesting! Great pictures and stories! Thanks for sharing. Makes me want to head out, I love the adventure

Many familiar place names. My family started exploring in SE Utah in mid 1960’s. Unforgettable beauty. Thank you for sharing this and I am looking forward to more chapters. Thank you.

This is extremely cool. Thanks as always Stiles! I’m always impressed by the archive you’ve been able to compile over the years, the photos really bring these scenes to life.

Also always surprised by how many NPS folks have crossed paths with Organ Pipe over the years.

Thanks Jim and Tug. What a gift! After camping around SW New Mexico over the holidays. I added a stop to revisit Canyonlands. Everything was closed, few people, 1 Ranger keeping eyes on things. Just to be there again was so satisfying. And a week later to have this great story to wind into my memories was just great. I had a couple of pics I thought Tug might like but cannot figure out how to post them.

Sounds perfect. Almost 1950ish.

Thank you for sharing this, Jim and Tug. I feel honored to help carry the torch for the “Friends of Arches and Canyonlands Parks: Bates Wilson Legacy Fund”. For those who don’t know, Tug helped start this organization to fill gaps in funding for the parks (when he wasn’t installing septic tanks, that is).

Tug, I more than appreciate our periodic conversations and “walking” down memory lane with you. I’m excited to read the rest of the series.

(Moab has certainly grown since the times described here, but how wild is it that my neighbor’s son works for A&E Electric? Still a small town after all.)