Come along with me then, I’ll take you to a Country where we shall have no need of Money to make us happy, nor Laws to make us wise; our Friendship shall be all our Riches, and Reason our only Guide; we may not say a great many fine things but we’ll take care to do ‘em.

—– Julio, the Indian, in James Miller’s play, Art and Nature

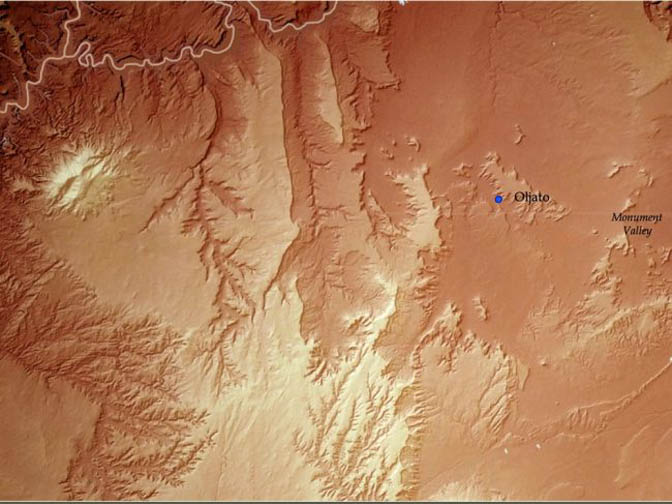

“You will have to leave,” the Navajo leader, Hoskininni Begay (Hashké Neiniihí Biye’: Son of Giving Out Anger), ordered John Wetherill on March 17, 1906 when he rode up to the water hole known to the local people as Oljato (Ooljéé’tó: Moonlight Water). Oljato is about twelve miles west of Monument Valley and, back in those days, was the center of a region that was difficult to access and many miles from the nearest white settlement. The only residents were Navajos and Paiutes who lived in their traditional ways, uninterested in European culture.

A journalist of the day had an austere perception of the “Navajo desert”:

“Vast stretches of arid sand and clay, dotted only with sagebrush; few streams, and those wholly uncertain in volume and season of flowing; widely separated tracts of timber; forbidding bluffs of bare rock; gray plateaus gashed with cañons whose walls have been carved by immemorial erosion into grotesque, half-finished architectural forms—these are the impressions the wayfarer gains of the Navajo desert. Picturesque, but not livable, is the universal verdict of those who are most familiar with it; and no one who knows the country is astonished to learn that it was originally selected for the Navajos in order to keep them forever out of contact with the whites on the assumption that no white man could subsist in such a chameleon’s paradise.”

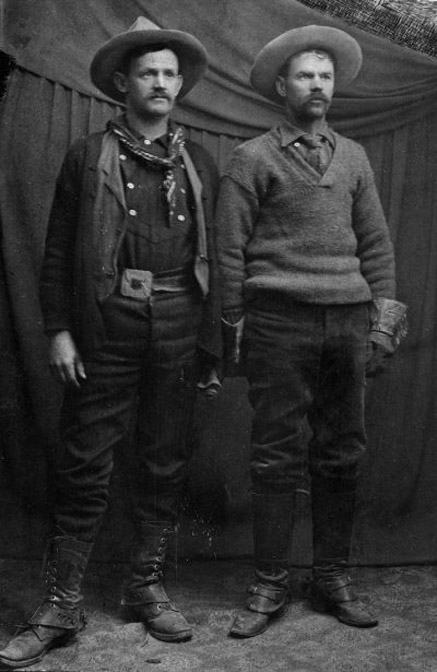

Wetherill did want to live there, and he had intended to arrive on the scene with a wagon load of food that he would supply to the People to demonstrate the benefits of having a trading post in their midst. However, after traveling about 150 miles from his home at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, the wagon broke down at Moses Rock, some thirty miles back. There he left his trading partner, Clyde Colville, and proceeded on horseback to Oljato, accompanied by his brother-in-law, John Wade, and some pack animals carrying a smaller quantity of the provisions.

Hoskininni Begay, with his escort of four armed guards, was accustomed to having his way. His father, Hoskininni, lived nearby. He was from the Tachini Clan—People from Among the Red Rocks. In about 1864, government soldiers came into the area to capture the Navajos and force them on the Long Walk to an internment camp at Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico. Many of the local people were taken away from their homes, but Hoskininni and his family cleverly avoided the captors. They were chased north and crossed the San Juan River into the rugged Cedar Mesa country. The soldiers and their Ute scouts were still hot on their trail, but Hoskininni used another crossing point near the Clay Hills to come back south of the river and evade the aggressors. His group hid out near Navajo Mountain until the threat of capture was past.

Then they returned to their homeland with as many abandoned sheep and other livestock as they could round up from the people who had been forced to leave. For several years they must have wondered whether they would ever see their friends again, but finally the captors returned with the hope of rebuilding their homes and communities. Hoskininni shared with them the offspring of the livestock that he had tended during their years of exile and helped them reestablish themselves.

In 1884, Hoskininni Begay was involved in an altercation with two prospectors—James McNally and Samuel Walcott—which resulted in their deaths. The government authorities were unable to arrest Hoskininni Begay, so they arrested Hoskininni, who had no part in the incident, and sent him to jail for his son’s crime. Hoskininni did not think much of white man’s justice after that, and he enlisted his son to help protect their community from future intruders.

Wetherill sent John Wade back to Moses Rock to help Colville retrieve the wagon. Now alone and vulnerable, he resolved to continue the conversation with Hoskininni Begay.

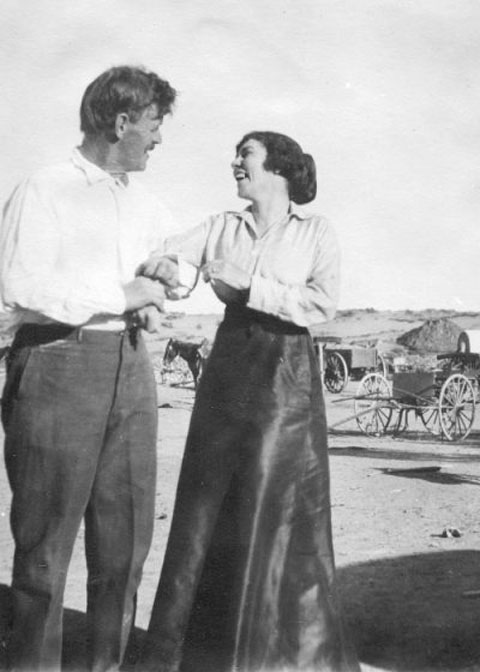

In the late 1890s, John Wetherill, his wife, Louisa, and their two young children, Ben and Georgia, who they called “Sister”, were living in the verdant Mancos River Valley of southwestern Colorado. Their home was a log cabin on a 160-acre homestead adjacent to the Alamo Ranch where John had grown up. They were finding that farming was a tough way to support a family. In 1896 their wheat crop was destroyed by an early frost. 1897 was the beginning of an extended drought. In 1898, rust claimed much of their crops.

John’s main interest, however, was not in growing produce, but in exploring the ancient cliff houses to the southwest and the rugged territory beyond. He supplemented his meager farm income by outfitting and guiding parties to the Mesa Verde archaeological sites, as well as more remote destinations. In 1898 he took two University of Minnesota professors on a horseback journey to the Hopi village of Oraibi to view the snake dance—more than 200 miles each way. In April of 1900, ethnologist Ales Hrdlička hired him to guide a foray through the southwest that was over ten times that length. They “visited all the major groups of Apache in Arizona and New Mexico: including the White Mountain Apache, the San Carlos Apache, the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apache, plus two Yuman Indian groups situated in northern Arizona, the Havasupai and Walapai.” Hrdlička “also studied most of the Indians of the Pueblo complex: the Hopi, the ‘Rio Grande Pueblos’ of Taos, San Juan, Jamez, Santo Domingo, Sia and Islete; and the ‘Western Pueblos’ of Laguna, Acoma, Acomita and Zuni.”

While John was away, Louisa struggled to take care of the two youngsters and maintain the farm. “I am so lonely I just do not know what to do,” she wrote. Maybe John could find another way to make a living that would not involve such long absences. A friend who owned a coal mine suggested that he start a fuel supply yard in Telluride—an opportunity that John rejected, as it was completely at odds with his adventurous personality.

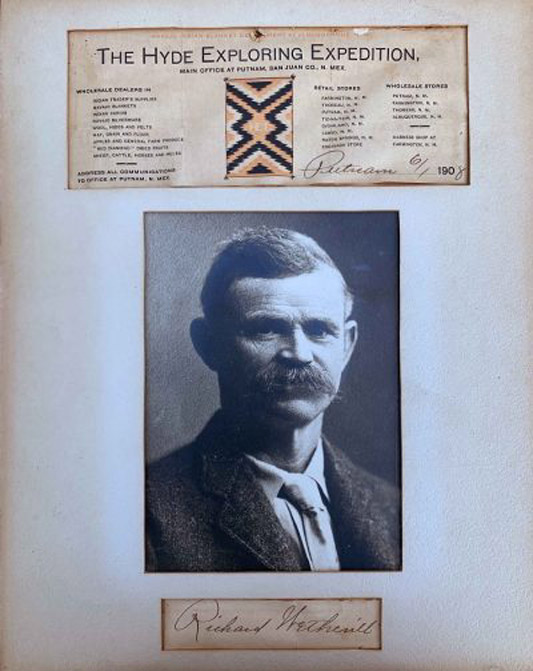

After returning home from his trip with Dr. Hrdlička, John headed south to Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico where his brother, Richard, lived. Richard offered John a job—operation of the Ojo Alamo Trading Post, which was located in the badlands of what is now the De-na-zin Wilderness Area some twenty miles north of Chaco Canyon. The wealthy Hyde brothers of New York, who were funding archaeological work at Chaco Canyon under the oversight of the American Museum of Natural History, had recently purchased the store and needed a proprietor. The clientele consisted of Navajo Indians and occasional travelers along the wagon road that passed through the property.

In November of 1900, John and Louisa packed the family’s belongings, left their Mancos ranch, and moved to Ojo Alamo. From that time on, the desert was their home.

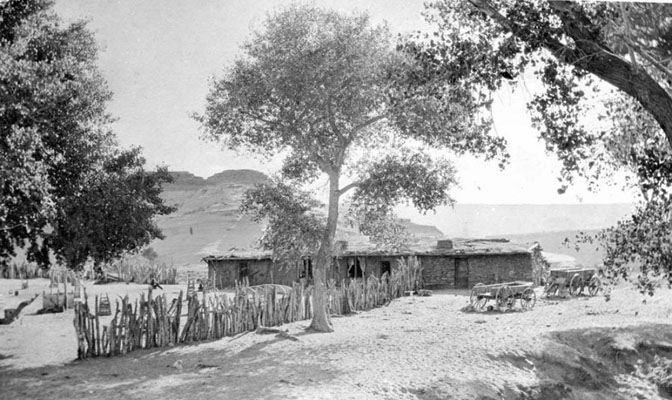

The landscape, although barren, is not without interest. Contorted rock formations, petrified logs, coal outcroppings, and dinosaur remains are evidence of an ancient marshland, but the days of abundant moisture are long past. The environment now appears hostile to life. The sparse vegetation is stunted and adapted to long periods of drought. The wildlife are not the lovable types—coyotes, packrats, jackrabbits, rattlesnakes, various species of stinging insects, and the like.

Louisa recorded her first impressions of the scene:

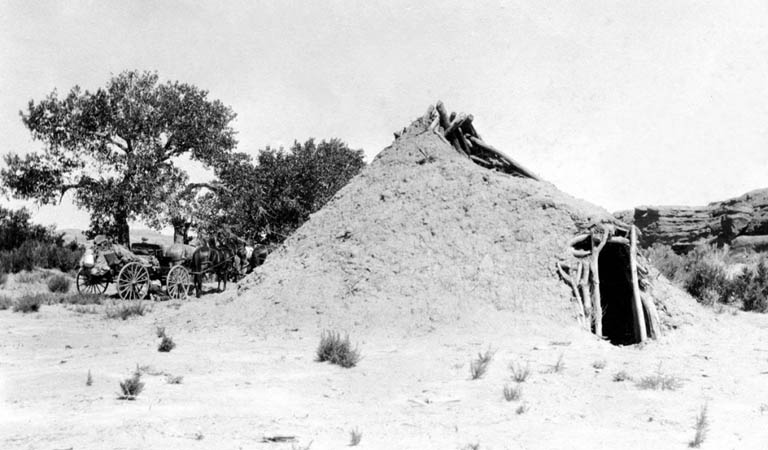

“It was all very strange. We could not understand anything the Navajos said. The country seemed barren. It was covered by snow. We had passed a few flocks of sheep and a few hogans on our way. The hogans were just circular huts with conical-shaped tops. They were built of poles, the top held up by means of several forked poles. After the poles are in place they are covered with bark, then mud. Then, over the mud, they are covered with loose dirt. An opening is left in the top by which the smoke can escape…. We could not see much of the hogans, as they were covered with snow. If not for the smoke coming from the smoke-holes, one could not find them.”

The wisdom of such a move was not evident to the folks back in Mancos. The costs of desert life were loneliness, hardships, and isolation from the security of civilization. Provisions were limited to those that could be hauled in over rough wagon roads from distant supply points, and the many niceties of society were no longer close at hand. Nevertheless, the Wetherills came to relish the change. John was no stranger to the desert, and he had developed a profound appreciation for it. Louisa was getting to know her Navajo neighbors, and the two children—Ben, who was nearly four and Sister, a year younger—were hardy and adaptable.

For Louisa, the experience became transformative. “One day a man came in and bought a bill of goods,” she recalled.

“He told me that he was having a ceremony at his house and said that there was to be some sand-painting…. When it was finished we were told to go into the hogan to look at it. I did not expect to see very much. We stepped inside the hogan and got the surprise of our lives. No one who had never seen a sandpainting could ever dream that anything so beautiful could be made just of sand. To look at the country around you, you would not think they could find so many different vivid colors, but they were there. The background was of plain sand smoothed, and, on this background, there were pictures of mountains, birds, antelope, corn, beans, pumpkins, and a plant they call mountain tobacco in red, blue, black, yellow, and white sands…. I decided I wanted to know as much as possible about the Navajos.”

The next spring, Louisa’s father, Jack Wade, came down to the trading post from Mancos. He told of a mineral outcropping he had seen to the remote Navajo country of northern Arizona on a prospecting trip in 1892. Might it be the place where two earlier prospectors, H. D. Mitchell and Charles S. Myrick, had found rich silver ore before they were murdered by Paiutes in January of 1880? Jack and John Wetherill resolved to find out. John could serve as an interpreter and negotiator with the local Navajos who had the reputation of discouraging intruders.

The two men assembled a pack outfit and headed out. To bypass the rugged mountainous country to the west, they took a circuitous counter-clockwise route around the Four Corners, the point where New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and Arizona touch. They journeyed north into Colorado, then west to a crossing of the San Juan River below Bluff, Utah. After fording the river, their next obstacle was Comb Ridge, a fifty-mile-long sandstone anticline topped with a sharp, undulating ridge resembling a cock’s comb. They scrambled over a pass formed by an uplift known as the Mule Ear Diatreme and then travelled southwesterly through the Monument Valley area, across the Arizona border, into the mouth of a hidden canyon known as Segihotsosi (Tséyi’ Hats’ózí: Slender Canyon), and up the side drainage called Adahchijiyahi (’Adah Ch’íjíyáhí: Where She Fell from the Cliff).

Jack Wade and John Wetherill searched for the ore ledge in vain, then headed back north. A short distance beyond the Utah border they came to Oljato. From there they continued north through Copper Canyon beneath the looming walls of Monitor Mesa to the east and No Man’s Mesa to the west until they reached the canyon’s mouth at the San Juan River.

The prospect of finding valuable minerals lured John and his father-in-law back to the Oljato country again in 1902. On their second trip they were accompanied by John’s brother, Clayton, John Clark, and Frank Lime. They found the mineralized rock outcropping that Jack Wade had remembered from a decade earlier, but assays revealed that it was of no commercial value. The source of the ore specimens that Mitchell and Myrick had found remained a mystery.

In 1902 the Hyde Exploring Company stopped sponsoring the excavations in Chaco Canyon and closed up all their operations. John Wetherill took over operation of the Ojo Alamo Trading Post his own account.

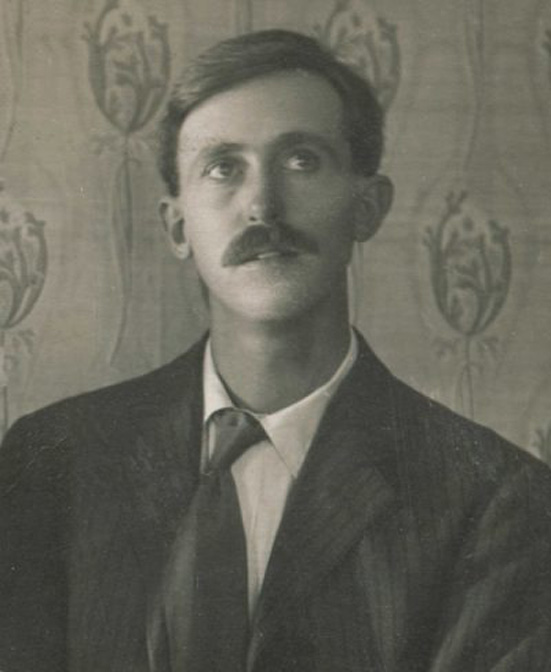

One day John Wetherill came riding to the trading post accompanied by a young man in a derby hat. The stranger, Clyde Colville, had been working for the Hyde brothers in their Farmington, New Mexico store, but its closure left Colville unemployed. Wetherill offered him a job at Ojo Alamo, and that was the beginning of a partnership that was to last for forty years. His involvement in the business gave John more freedom to explore and guide clients into the back country.

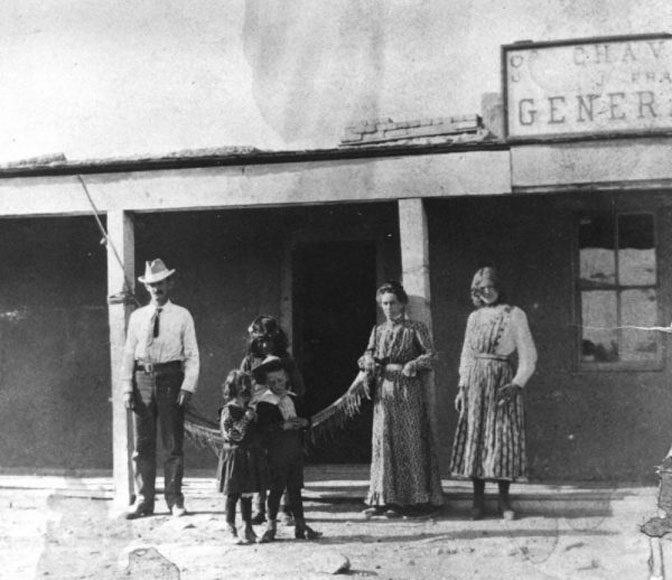

The business was suffering as a result of an extended drought, which had begun back in 1897. The Navajos had to range long distances to find grass for their sheep and horses, and the Ojo Alamo area was nearly uninhabited. The Wetherills thought of the prospects of moving their trading operation to the Oljato area in distant Utah where the People had no nearby access to trade goods. John loaded a wagon with supplies and began the long journey to that district to see if the local residents would be interested in such a proposition. He struggled with nearly-impossible road conditions and had to turn around short of his destination. Then, in 1903, a less-appealing opportunity came up to run a store in Chavez, New Mexico, just east of Thoreau along the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad. The Wetherills accepted the job and left Colville to run the Ojo Alamo post.

Much of the Chavez business was from local settlers and travelers, and the Wetherills missed their visits with the Navajo people. In 1904 they decided to move north to Chaco Canyon, where John’s brother Richard lived, and consolidate their trading operations there. They would again have some Navajo neighbors.

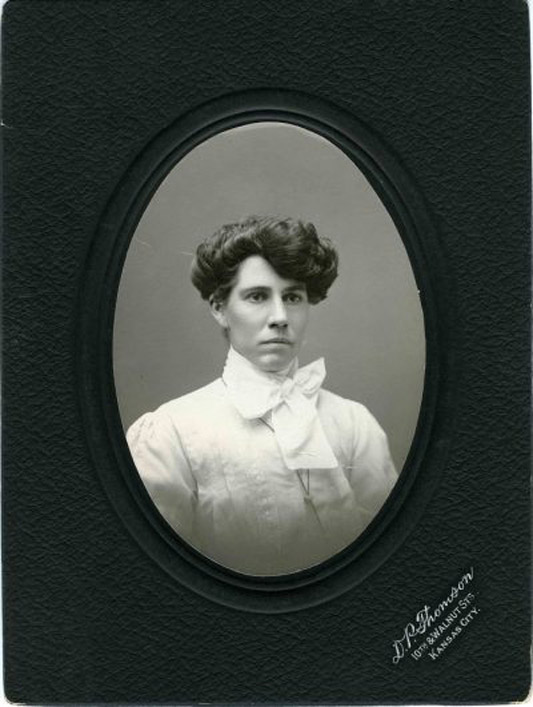

By that time, Louisa had developed a profound respect for the People and had begun a study of their traditional way of life. Since moving to New Mexico, she had applied herself to learning the Navajo language and was now able to converse with the old-timers. Her intense interest in the Navajos was a profound cultural shift for her. Her grandfather, James Martin Rush, had been an Indian fighter, and her family members viewed the local Utes around Mancos with suspicion and dislike. It was only through John’s influence that Louisa began to see the beauty and wisdom in the traditional Navajo way of life.

John’s father, Benjamin Kite (B. K.) Wetherill, was born in Pennsylvania in 1832. His family were members of the Quaker religious denomination, also known as The Society of Friends. As a boy, B. K. attended the Friends’ meeting house in Chester with his family, and, as a young man, he received a liberal education at the Society’s Westtown Boarding School. John’s mother, Marion, was also a member of the Society, and the parents involved their children in Quaker activities while they were growing up in Leavenworth, Kansas.

The Society of Friends originated in England in the mid-seventeenth century. Their theology is distinguished by a belief that all people, regardless of race, cultural affiliation, social status, or level of education are endowed with Inner Light that serves as a moral guide. This Light, they believe, involves a sense of direction that can help guide the recipient’s decisions even before the course is intellectually clear. An early Quaker minister described this concept succinctly when he observed, “I have often found it good to adhere to impressions felt though at the time I knew not for why or what”.

Quakers believe that Inner Light is the birthright of all people, but that not everyone is in touch with its subtle guidance. Various distractions can cloud the senses and cause the individual to lose sight of its message. To avoid such impediments, the Quakers advocated a simple lifestyle that avoided activities designed to artificially manipulate their emotions. This lifestyle gave them an affinity with other societies who were unencumbered by the complexities of modern life, such as Native Americans.

Quaker beliefs often conflicted with those of the predominant culture and were radical with regard to their perception of Native Americans. For example, based on his observations of the Cherokee tribe, which he visited in 1775, William Bartram, a Quaker botanist from Philadelphia, observed their “friendship without fallacy or guile, hospitality disinterested, native, undefiled, unmodifyed by artificial refinements”. Of the Creeks, he wrote, “As moral men they certainly stand in no need of European civilization. They are just, honest, liberal and hospitable to strangers; considerate, loving and affectionate to their wives and relations; fond of their children; industrious, frugal, temperate and persevering; charitable and forbearing”. His observations contradicted the prevailing belief that religious training, education, and the civilizing influences of modern society are necessary for the development of morality and that Native Americans were inferior in this regard.

B. K. Wetherill was involved with Native Americans when John was just a boy. After the Civil War, some of the midwestern Quakers became appalled at the brutal treatment the plains Indians were receiving. A group of Iowa Quakers petitioned the federal government to change their manner of dealing with those conflicts. “The recital of the tale of the poor red man is absolutely humiliating to our Nation, and disgraceful to our race,” one of them wrote. “Our entire policy with them should be changed.” As a result of the lobbying of that group and others, president-elect Grant, in 1869, agreed to turn over management of the Central Indian Superintendency to the Orthodox Quakers. In 1872, B. K. Wetherill was hired to work at the Osage Agency at Pawhuska, in what is now Oklahoma. After a few months on the job, he was reassigned to serve as a trail agent with responsibility to prevent conflicts between the Indians and whites. Over the next few years, he spent a considerable portion of his time with the Osages in their hunting camps and developed a deep respect for them. He passed on his insights to John, and John passed them on to Louisa.

Louisa came to realize that her study of the traditional Navajo way of life was at a disadvantage in her current surroundings, because her Native American neighbors no longer followed some of their ancient customs. “We lived on the east side of the reservation where there are a good many English and Spanish speaking people passing and where the Indians are taking on more or less of the white man’s ideas and losing a good many of the former teachings and ceremonies,” she lamented. She wanted to live in a place where the Navajos still practiced their old ways. Oljato was one of the few outliers in the Southwest where European culture had not yet intruded. John was also attracted to the Oljato region for the same reason and also for the new opportunities it would provide for exploring the rugged country surrounding it.

Early in 1906, John Wetherill decided to again try to get a freight wagon full of trade goods into the Oljato country so he could assess the willingness of the residents to go along with his trading post proposal. This endeavor is what led to his encounter with Hoskininni Begay on March 17.

John used his quiet diplomacy and kind demeanor to convince the Oljato residents that he could be their friend. He suggested an all-day feast of rabbits provided by the local people and flour, coffee and sugar that he had brought in, and he showed them the advantage of having a source of provisions and a local place to sell their wool, goatskins, and weavings. After the feast was over, Hoskininni Begay and his father were pleased and told John that the Wetherills would be allowed to stay and build their post there. In the meantime, John Wade and Clyde Colville had repaired the wagon, and they arrived at Oljato with the rest of the supplies. They set a board across some coffee boxes to use as a trading counter, then John Wetherill headed back to Chaco Canyon to tell Louisa the good news and obtain another wagon load of provisions.

Back home, Louisa insisted that the next trip to Oljato be a move of the entire family. When they announced their plans, the local Navajos warned them against it. The inhabitants of that region were dangerous, uncivilized renegades, they were told. “Those stories did not daunt us,” Louisa said. “We were not afraid of the Navajos, and we did not think we would have any trouble with the Paiutes.”

The route they decided to take was a more southerly one via Gallup, across the Arizona border through Fort Defiance, Chinle, and Round Rock, then across the Utah border to Oljato—a distance of nearly 250 miles. Their caravan consisted of two wagons loaded with all their earthly possessions and goods to trade with the Indians, a buggy, fourteen horses, three cows, several chickens, and two pet rabbits that the children insisted be brought along. John drove a wagon, Louisa drove the buggy, and Ben (age nine) and Sister (age seven) rode horseback. A young man, Orson Eager, drove the other wagon, and Lillian Scurlock, a young woman who lived with the family, and Maude Wade, John Wade’s wife, made up the rest of the party. The journey was a long and difficult one. They struggled through mud and sand for much of the way.

When they reached the half-way point at Chinle, Arizona, the Navajo people there reiterated the concerns of the New Mexico folks. “Don’t go. There are bad people there. They will kill you.” These warnings did not hold them back. From there on, they made their way across rough, roadless terrain until they at last approached their destination.

Contrary to the dire warnings, the travelers found the people of the new homeland to be kind and hospitable to a remarkable degree. “On the nineteenth day, our progress was halted by a deep arroyo with steep cut banks,” Louisa recalled. “After surveying the situation, we estimated that it would take us two days of hard work to build a route across it. Suddenly, while we were still contemplating our predicament, we saw Navajo men, women, and children walking toward us from all directions. They were not the least bit hostile, but were all very friendly. After we ate lunch together, the men helped us build the road. In just half a day it was passable, and we were so grateful to be able to camp on the other side that night. We knew then that we were going to like our new friends. The next day we reached Oljato.”

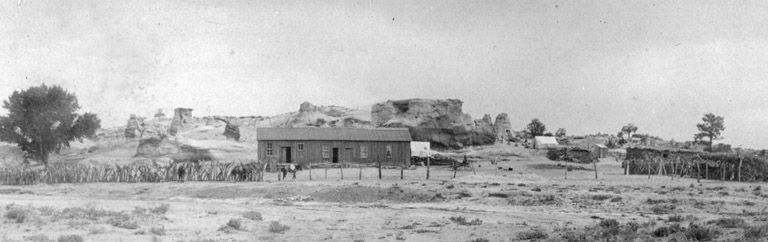

Clyde Colville and John Wade rejoiced at the reunion with their compatriots. They reported that they had nearly run out of supplies and were almost ready to abandon their post. Erecting tents, the Wetherills set up a more substantial temporary establishment, and then they enlisted some of the local people to help them build a permanent structure. Soon the rustic, but gracious Wetherill & Colville outpost came into being. A passing journalist recorded his impressions of the scene:

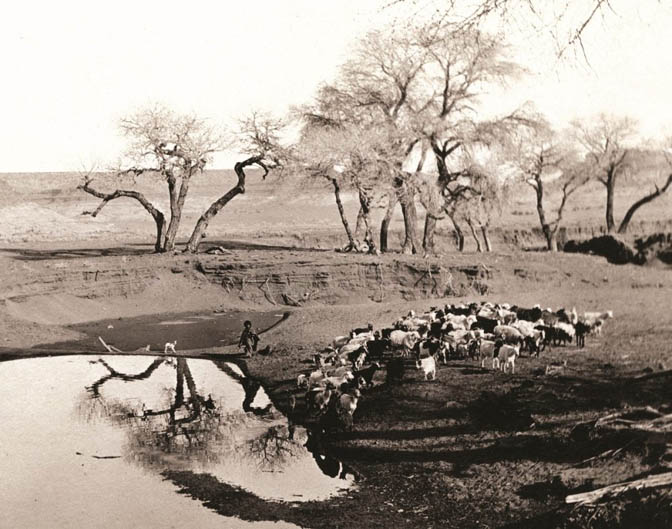

“Oljato, which consists of a cottonwood tree, a spring of water and lone house, lies directly to the southwest just three-quarters of a mile north of the Arizona line and is possibly one of the finest examples of existing frontier trading posts. Mail reaches the place but once a week and is carried horseback by a Navajo Indian medicine man. Supplies are brought in by way of Gallup in Arizona by ox teams, taking about 21 days to make the trip. The hills about are crowded with goat herds owned by Navajos, and it affords a most picturesque sight to see them shooting down over a barren stone ridge or through yellow sands followed by an Indian boy or girl with their bows and arrows, most probably more interested in finding a lizard or a snake than in the welfare of the goats. The romantic hogans are pitched promiscuously in old corners and the Indians wander around quite contented with their allotment in life.”

Over time, the local people came to accept the Wetherills as dear friends. They called John “Hosteen John”, which was a title of respect, and Louisa they called “Slim Woman”. Hoskininni considered her his granddaughter. (For more on Louisa, see my article, “Slim Woman of Kayenta,” in the February/March 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

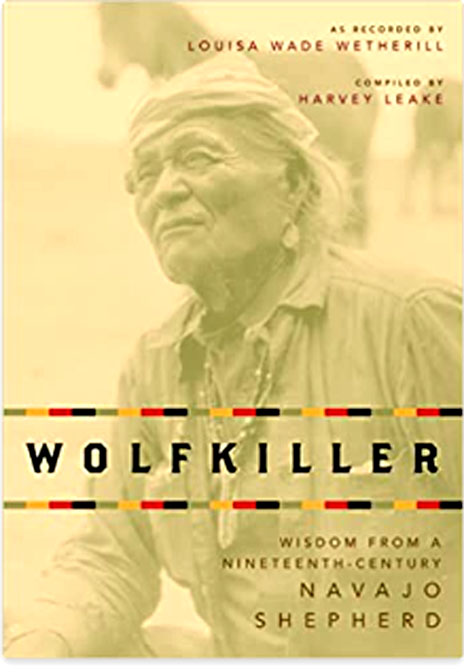

Louisa found unexpected depths of beauty and wisdom in the traditional Navajo way of life. She recorded how one of the men who helped build their house exemplified those values. “Among the Navajos who were working there was one man who we particularly noticed. He was always smiling and was very quiet. He never took part in any kind of an argument, which sometimes came up among the others. He always went on about his business, paying no attention to what might irritate some of them. He never gambled, and we noticed they all had a good deal of respect for him. They called him the Wolfkiller.” Her new friend recounted to Slim Woman the insightful training he had received as a youth, and, years later, Louisa translated and recorded his stories for posterity. (For more on him, see my article, “The Wisdom of Wolfkiller: A Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd and Sage,” in the October/December 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

The Wetherills’ arrival at Oljato in 1906 was just the beginning of their residence on the northern Navajo frontier. When Hoskininni died in 1909, Louisa was the executor of his estate. In 1910 the family moved about twenty miles south to Kayenta, Arizona where they lived the rest of their days. They continued their friendships with their Navajo neighbors until the end

*****

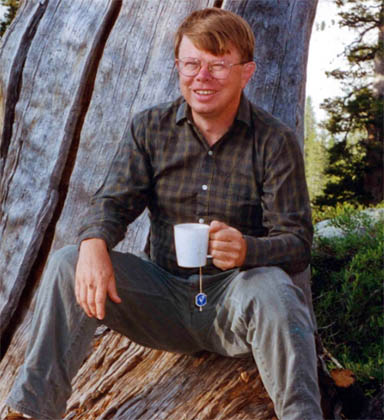

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

To peruse all of Harvey’s brilliant Zephyr contributions, click here.

TO COMMENT ON HARVEY LEAKE’S STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE.

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

$55 Each or Two for $100 (Free Shipping.)

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

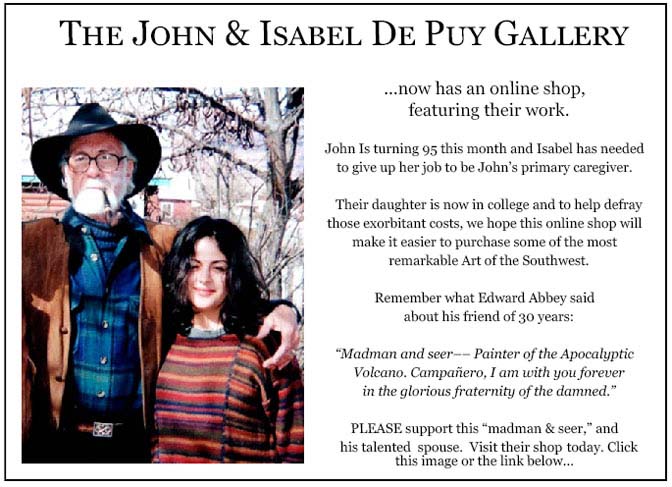

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

PLEASE BE SURE TO LEAVE A COMMENT ON HARVEY’S STORY. JUST SCROLL A BIT MORE!

What an interesting life the Weatherills had! They were truly pioneers in that forsaken country which they found so beautiful and whose people they treasured as friends! They, with their understanding and respect for the People, faired much better than the Caucasians who felt it necessary to take Indian children away from their families and send them to boarding schools!

It warms my heart to read a story like this and know that it is fact not fiction. If it were not for folks like this we would all still be huddled up on the east coast. Learning the language was a very smart move.

All of the articles that Harvey Leake has done for the ZEPHYR are fantastic, and there have been many of them over the past years. Be sure and check them out!

Kayenta has the Wetherill Inn, which I am sure is named after these intrepid settlers, but it is a modern structure with no vestiges of the lives and history of its namesakes. Goulding’s Trading Post in nearby Monument Valley was established around 1920, and served the Native populations for decades. It naturally expanded into a tourist operation after Harry Goulding enticed movie companies to Monument Valley in the 1930s. Due to his foresight, the red rock spires of MV are legend, and are recognizable to people throughout the world as Indian Country, and, many Navajo families were able to find employment during the depths of the Great Depression. Recently, the Goulding family—after 103 years–sold the trading post, campground, general store and other amenities to the Navajo Nation. Its future is unsure if not downright bleak. Why did they sell? Gouldings was having to pay property taxes–very high property taxes–to both the Navajo Nation and San Juan County. Neither would grant the family enterprise relief, and with arrears piling up, they were forced to sell their family legacy; a piece of treasured history.

I’d never heard that. Thanks for the info.

Thank you for this info. So sad to see the things that are being lost to the greed of man.

Please Ms. Haun keep doing what you do to educate & promote the America West .

Great article Jim, thanks.

This was an absolutely fascinating account of these brave pioneer people! Thanks for bringing it to us!

I have a number of letters on Hyde Expedition stationary written by a Joseph Colby who was an agent at Putnam. in the years 1901-02. He was from the east and describes much about daily life in such a remote area. I have transcribed the letters into a book, but I am still not sure what to do with the originals. I would post photos of the letters on this site if I could. Fascinating stuff!

Hi Greg. I had to put restrictions on the Zephyr Facebook page. Every photographer, professional or amateur, wanted to use this site to promote their own work.

If you can scan and send them to me, via email, I can repost along with your text.

Great article, thanks Mr. Stiles

I just ordered the Wolfkiller book & cannot wait to read it

at times sad, mostly just awe-inspiring, good remembrance ~

A few years ago I visited Olijato for the purpose of getting professional quality photos of the abandoned trading post for a friend to use in seeking to have the post restored. Dr. Robert McPherson had an intense interest in the history of the old post. His goal was to see it rebuilt. The last I heard there was a lot of progress being made in finding the money needed. Most of the post is still there, although in poor condition. As expected a local came by to see what we were doing. He was friendly to us.

Nice article it helps me relate to my own family history, who owned several trading posts in the four corners region, and also lived in Mancos for some time. My 2nd great grandfather William Hyde was called Nakai Nez (Big Mexican) by the Navajo, because he was big, swarthy, and spoke Spanish. He also spoke Navajo and Ute. I was walking with my grandad in Cortez one day when we met an elderly Navajo gentleman and they spent about 10 minutes speaking in Navajo, I was a bit surprised as I knew little of the family history at the time. They had grown up herding my great grandads sheep together. When the Mexican sheepherder Juan Chacon was foully murdered by Everett Hatch he had a check in his pocket from my great grandad and his partners sheep company after herding sheep for them all summer. I knew a lot of Navajo kids growing up but never learned anything but a few cuss words! I know Im going on about my family rather than the article but thats where it took me

Louisa sounds like a fascinating person- it would have been interesting to talk to her and I will definitely check out the stories by Wolfkiller. She mentions mountain tobacco in the sand painting, I recently learned something new about that plant, it is preyed upon by a type of moth, and when this occurs the plant releases a chemical that actually attracts a different insect that preyed upon the moth. Pretty neat how everything in nature inter-acts.

Thanks Jim as always great stuff.