A 2024 PROLOGUE:

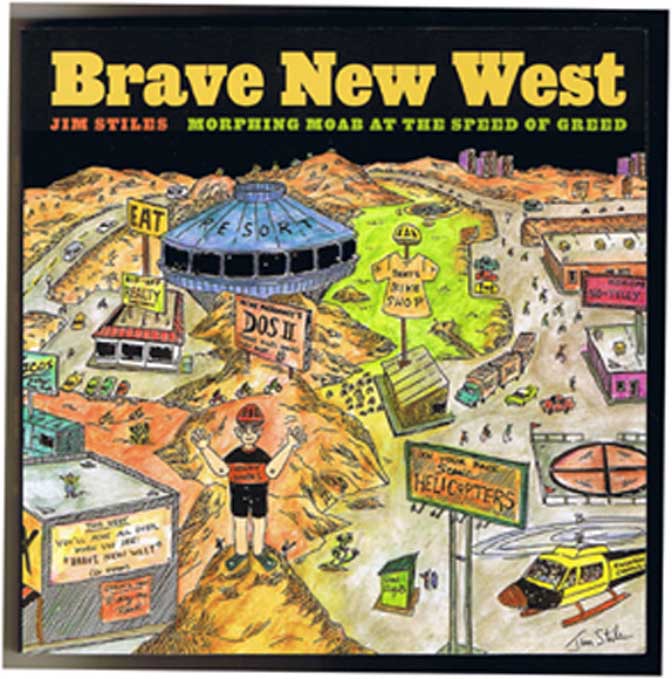

On August 1, 2005, I submitted a manuscript to the University of Arizona Press. I had been approached by UA’s university press two years earlier, and had signed a contract soon after. I called it “Brave New West: Morphing Moab at the Speed of Greed.” The substance of the book was complete, but like any other book, subject to the needs ot whims of the publisher, getting the book into the hands of the intended readers is a long, arduous and frustrating experience. After requests to reduce the word count by thousands of words and delays by UAP in the production process, my weird looking square little book finally reached bookstores in March 2007. Even in those 20 months between submission of the text and publication, the “New West” and the amenities economy that had created it, was in an extreme state of flux. Or at least it seemed extreme to me.

I had been ranting for years about the impacts an Industrial Tourism economy could create. My pleas fell on deaf ears, especially with the mainstream environmental community. Organizations like the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA) embraced the change and even devoted an entire issue of its newsletter praising the amenities economy as a clean, non-polluting way to bring economic prosperity to areas that had previously depended on the extractive industries to survive. What they failed to consider was that while coal mining and oil and gas exploration and ranching could scrape bare the skin of the rural West, a massive monolithic tourism economy would eventually bare and destroy its very soul.

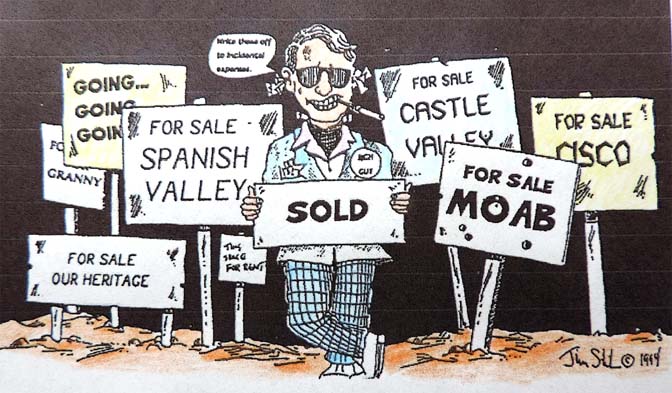

When “Brave New West” was published, I had seen the explosion of condo developments across the Moab Valley and a bevy of new motels and fast food restaurants. Tourist visitation had increased as well, and at Arches, their numbers inched past 900,000. If one could find any comfort in any of this, it was the consensus that, at least, it couldn’t get much worse.

Of course, nothing could have been further from the truth.

In 2002, after living in Moab and at Arches for over twenty years, I finally sought refuge 55 miles to the south in San Juan County. Safely ensconced with my Mormon friends (who proved to be an excellent deterrent against California Expatriates) I watched Moab’s transmogrification from a relatively safe distance. What has played out in Moab still amazes me.

*****

Recently I received a few emails from desperate New Moabites, new residents who had come to Moab in the last decade or less, and who were appalled by the changes that have kept coming, in wave after wave, relentlessly,and with no end in sight. The people who contacted me had heard I’d been a voice against out-of-control growth and wanted me to “do something.” When I failed to respond to one especially desperate plea for “Zephyr Action,” he expressed his disappointment at my lack of concern or engagement. I suggested he read “Brave New West;” I don’t know if he took my advice, but I never heard from him again.

When you read this, you might understand why I’ve lost my zeal. But to at least understand how Moab got from there to here, and whatever comes next, it’s worth the time to give this a read. It might at least help you to understand the roots of this Moab Debacle. —JS

FROM BRAVE NEW WEST/ 2007: “AN AMENITIES BOOM…& MELTDOWN“

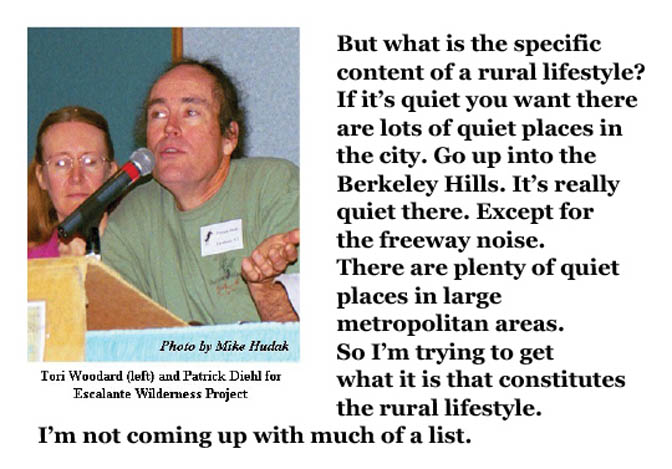

Patrick Diehl is an outspoken environmentalist and a strong advocate for change in the Rural West. In fact, he’d like to dismantle it completely and start over again. Diehl ran for the U.S. Congress a few years ago on the Green Party ticket and received 2% of the vote, not bad for a guy who, until recently, lived in one of the most remote communities on the Colorado Plateau (Diehl and his wife recently moved back to the West Coast). Escalante, Utah is eons away from becoming the next New West town. It is rural to its roots and proud of it. It has earned a reputation with some for being one of the most intolerant towns in Utah, but even some environmentalists believe that Escalante simply wants to hold onto its lifestyle and its history. The clear message, in any case is—-don’t try to change us. Diehl was ready for a change, or more precisely, a revolution.

In 2002, The Zephyr interviewed Patrick Diehl and his wife Tori Woodard at their home in Escalante. Their neighbor and Zephyr contributor Erica Walz interviewed Diehl at length about his views on what he called “The New Economy.”

“The ‘amenities economy’ idea,” Diehl explained, “that the Wilderness Society was putting out is what I think lies (ahead). There’s still a fair amount of merit to this concept. Between the extractive economy and the purely touristic economy is a third way in which you have people moving to an area to live there and be part of the local society and perhaps the local economy–in many cases bringing their jobs with them and telecommuting–and the reason people come there is because it’s a beautiful place to live. It’s not going to be healthy and beautiful if you degrade it through logging and mining and grazing. It involves replacing some of the extractive economies. But I’m much less confident in the future of this economy (in Escalante) than I was four years ago when we moved here, and I also see that the savagery of the local resistance exceeded even my expectations. People will go very far to make their area be extremely unattractive to outsiders. It has to do with political power. If you let outsiders in, if you allow them to organize and voice their point of view you can easily lose control. These small towns have a lot to lose from a political standpoint if there’s much influx from outside. So the chances of actually getting an amenities economy going in southern Utah is very bad in the short run because of the political situation.”

Diehl wasn’t willing to completely abandon the rural population and believed work could be found for them if this New Economy took root. For instance, he believed a massive effort to cut and treat and remove the exotic plant tamarisk would attract a great number of the old locals, “if they were paid for it.” But for the most part, Diehl wanted to see a dramatic turnover in small rural communities like Escalante, even its population…

“I think this town needs to double in size. If we’re going to have more towns in this part of the world they should be more self-sustaining. They’re really untenable. Not just in economic terms but as cultural units. Maybe 50 or 100 years ago when they were cut off from the outside world they had to create their own culture, but right now it feels like the further reaches of Provo to me–it’s nothing, in itself.”

What about people who enjoy it the way it is?

“I can’t imagine enjoying it. I really loathe this town, and you can quote me. Socially it’s a really loathsome place. You can put that in the paper. Absolutely. It’s the worst place I’ve ever lived, and I’ve lived quite a few places. So some people like it–it’s like there’s no accounting for taste.”

Ultimately, Diehl’s failed vision of a New Escalante only frustrated and embittered him. When Patrick and Tori left town for good, they left few friends behind. Escalante still holds onto its rural culture, backward as some people may see it, and intends to stay that way. Moab, on the other hand, could not have been riper for change.

Moab’s “funky little town” reputation and its odd cultural diversity made us a prime target for the New West. Although we bickered and fought, the various factions in Moab at least co-existed. As a result, a level of tolerance, albeit shaky at times, existed in Moab that wouldn’t have been found, even 50 miles down the road in Monticello. Ultimately, it was people like me who in a perverse way made the Brave New West Invasion possible.

Fifteen years ago, Lance Christie summed up the future in his Zephyr “Boom and Bust Baloney” essay when he wrote:

“If a community uses wilderness amenities as a drawing card, then offers goods and services people want when they come to enjoy the local amenities, wilderness can make the people selling those goods a lot of money. If the community resents visitors and opposes wilderness for taking away the freedom to dig holes searching for treasure, then wilderness (or any tourism) won’t make them money.” Christie was prophetic in more ways than one when he added, “The whole economic debate over wilderness tends to distract us from the fact that the major reasons for designating wilderness arise from non-economic values.”

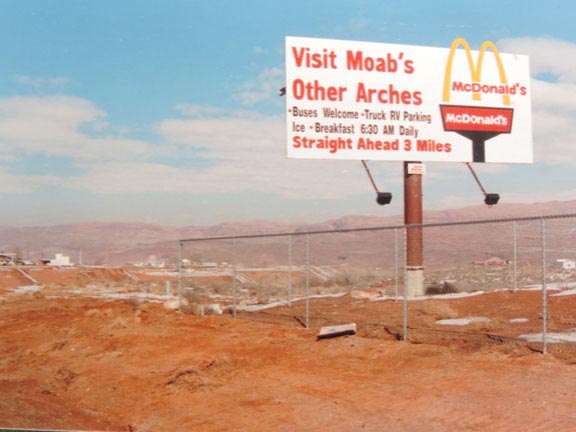

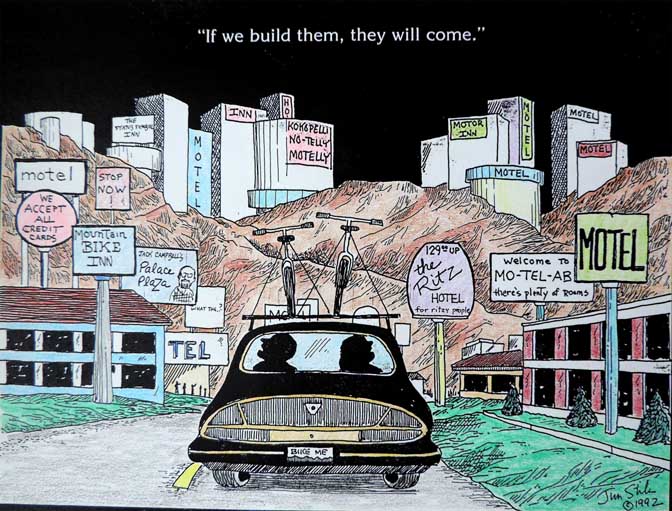

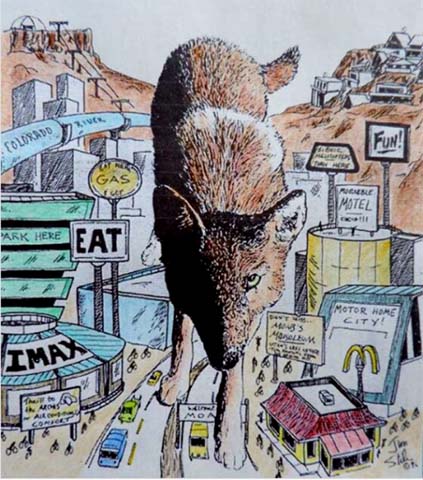

Indeed—yet that is exactly what happened. When Moab’s amenities economy really gathered steam in 1993, when seven motels were constructed in a matter of months and nationally franchised fast food eateries like McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Denny’s, Arby’s, Taco Bell and Burger King began to sprout along Main Street, when recreational visitation increased exponentially on surrounding public lands, and when none of the major environmental organizations expressed concern—not SUWA, not the Sierra Club, not The Grand Canyon Trust, not the Wilderness Society, it was as if they didn’t even notice.

Some were loathe to praise the specific consequences of the amenities boom, and privately expressed horror at the explosive and uncontrolled growth, but no one wanted to be on the record opposing it. It was, after all, their idea. In fact, some organizations went to great lengths to praise the stunning changes occurring in Moab and elsewhere, but always in broad vague strokes.

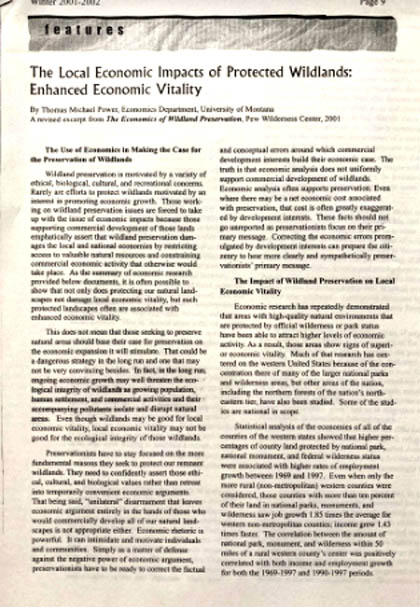

In 2002, SUWA printed a feature story in its winter issue of “Red Rock Wilderness,” their quarterly newsletter. It was called “The Local Economic Impacts of Protected Wildlands: Enhanced Economic Vitality.” It was written by Thomas Michael Power, a Professor of Economics at the University of Montana.

Power and his data asserted that protecting the Rural West’s wildlands did not damage local economies; on the contrary he believed that “protected landscapes are often associated with enhanced economic vitality.” (emphasis added). But he followed that declaration with a curious caveat, considering the intent of the article, that was all but ignored by environmentalists. Power warned:

“This does not mean that those seeking to preserve natural areas should base their case for preservation on the economic expansion it will stimulate. That could be a dangerous strategy in the long run , and one that may not be very convincing besides. In fact, in the long run, ongoing economic growth may well threaten the ecological integrity of wildlands as growing population, human settlement, and commercial activities and their accompanying pollutants isolate and disrupt natural areas. Even though wildlands may be good for local economic vitality, local economic vitality may not be good for the ecological integrity of those wildlands.” (emphasis added),

The remainder of Power’s essay moves away from that warning. Using the data he had gathered, Power struck several blows in support of the amenities economy. He noted that “higher percentages of county land protected by national park, national monument, and federal wilderness status were associated with higher rates of employment.” He discovered that population growth in areas near wilderness areas was higher than state averages. And Power observed that Wilderness “protection was associated with growth rates two to six times those for other non-metropolitan areas.”

Power concluded, despite his early warning, “It is not clear why wildlands advocates would not want to meet the economic critics of wildland protection on their own ground, while also continuing to make the ethical, cultural, and environmental arguments. After all, if you can take away the only powerful argument the anti-environmentalists have, why would you not do so?”

(2024 UPDATE: RETURN to MOAB FOR 17 MINUTES By Jim Stiles) I had not been to Moab, to really observe the changes, in a couple years. Its had been February 14, 2017, the date of our defamation lawsuit hearing, that had brought me back previously. We prevailed at that hearing, but the lawsuit dragged on for two more years. This visit was at least not related to litigation. Still it was a sock to my system. And one more reason why, after 35 years, there’s not much left in Moab for me, persona;;y at least, to fight for…JS

It was as if he was saying, we can let the anti-wilderness people destroy the West on their terms or we can fight to destroy it on our terms. And aren’t our terms of destruction better than theirs? After all, before we destroy the wilderness, we’re going to protect it.

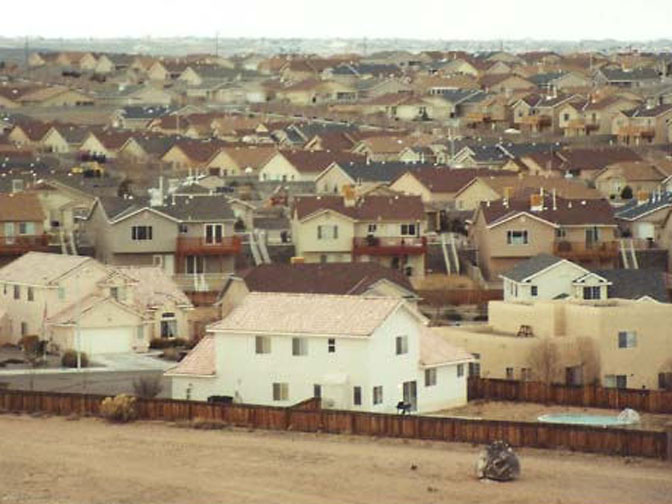

Environmentalists failed to see or would not acknowledge the double-edged sword Power offered. In a subsequent issue of “Red Rock Wilderness,” SUWA attempted to put its own spin on Power’s report with some additional numbers of its own. SUWA noted that, “Total employment in Utah has increased by 45% in the last decade…What is fueling Utah’s pacesetting growth? Tourism and related services have been especially robust, and now provides more than a third of all jobs….Growth is not limited to urban Utah. In Grand County, a tourism explosion helped to make it the third fastest growing county in Utah.”

All of this was told with almost evangelical enthusiasm. None of Power’s warnings saw the light of day in this particular spin. Finally SUWA noted the ballooning Utah population, which grew by 30% in the 1990s. “This tremendous regional growth, with Utah at its epicenter, is driven by Western quality of life factors like outdoor recreation, open space, and wilderness….There is a very real place for wilderness in Utah’s economic future. Protected by BLM, wilderness can serve as a modest sustainable source for economic well-being and community development.”

There’s nothing “modest” about Moab’s transformation in 2005. Some environmentalists might argue that much of the explosive change in Moab has nothing to do with their efforts to support a clean, upscale amenities economy. The rowdy raunchy Jeepers and the noisy noxious ATVs and the rabid Rock Crawlers seem to have nothing much in common with the leg-powered bicycle as a recreational diversion. It might be fairer to suggest that the amenities economy backfired in the environmentalists’ very own faces.

Except for the annual Jeep Safari itself, Moab was never much of a destination tourist center. Travelers passed through Moab as quickly as a ride to the Arches and a daily raft trip required. It wasn’t until the late 1980s, when bringing your bike to Moab was like making a trip to the Wailing Wall, that enterprising men and women everywhere began to seriously take note of Moab. Clearly Moab had achieved that special status reserved previously for places like Telluride and Aspen and Jackson, Wyoming…Santa Fe…Sedona. Just a handful of small towns around the West that suddenly, one day, discovered they had cachet….that mystical undefinable quality that makes everyone want to be able to say, “I’ve been there.” What motivated entrepreneur could miss something like that? You could hear the wheels turning inside their minds:

If everyone knows about Moab now, and everyone thinks Moab is a cool place to be, and if bicyclists will come here in huge numbers and spend massive amounts of money in this economy, why can’t we do the same thing with other forms of recreation? Why not a hill climb for dune buggies? Why not a rock crawling event? Why not BASE jumping? Or rock climbing? Or canyoneering? Or skydiving? Or ATV jamborees and races? Why not anything that can make us a buck and pull more visitors to Moab? Who’s going to complain?

Truthfully, hardly anyone. Some environmentalists bitterly oppose the dramatic growth in the use of ATVs in Southeast Utah and subsequent resource damage, but how did the environmental community ever think it could limit the amenities economy to the kinds of functions and activities only they approved of? There’s little comfort in knowing that imitation is the highest form of flattery. But the truth is, after Moab cut its teeth on bikes, the sky was the limit, no matter how dissimilar the activity might seem to some. It still is.

*****

When Thomas Power set out to analyze the effects of wilderness on the rural economy, he noted an anomaly that he could not initially explain. “Researchers,” he wrote, “puzzled by the growth of population in western Montana, despite low wages and incomes, studied the location of new residential housing to determine what locational characteristics explained the decisions homebuilders were making. They found that the closer a location was to a designated wilderness area, the higher the likelihood of new construction. The same was true of national parks.”

Power’s bewilderment is old news to most of us who live in small communities near parks and wilderness. New home construction, which took off in Moab during the early 90s, is often intended for part-time residents, people who have no intention or need to seek employment in the area. In fact, these homes and condominiums are in a way, very disconnected from the socio-economic needs of the community to which they have, at least physically, joined. They exist in something of a vacuum, because so many of these part-timers are oblivious to the issues and problems that affect the town. They don’t know much of the town’s history and know few of its citizens, they don’t get involved in local politics and don’t vote. They do pay taxes and they don’t impact the educational system because most part-time residents don’t have school-age children, but they still demand the services that they believe their tax dollars entitle them to. In almost every case, this kind of second home community negatively impacts the tax base; in other words, when towns grow in this fashion, everyone pays more.

But rarely will the environmental community acknowledge such facts at a time when candor and the truth are the most effective weapons we can hope to possess to support our point of view. And to me, candor and honesty have gone missing from ‘our side’ of the debate for a very long time.

Or perhaps it runs deeper than that. Perhaps candor is a matter of interpretation. Within the conservation movement, there is a growing dichotomy between the more idealistic Thoreau-types and the New Environmentalists who have embraced the kinds of land preservation strategies that concern me so deeply. The two groups can look at the same tree and see different colors. Let me offer an example.

Lance Christie frequently posts information and analysis (his own and others’) in emails to a number of friends and associates, so when an email came across my monitor titled, “Rich Weasels in Aspen do something right,” I paused to give it a read. “Rich weasels” is a name I’ve used frequently in the Zephyr, so I had personal interest.

Here was Lance’s observation:

“Under the Pitkin County building code, every new and remodeled home in Pitkin County must meet a strict ‘energy budget’ of approximately 40,000 British Thermal Units (BTU) per square foot. Nationwide, the average home consumes 63,000 BTU per square foot per year.

“Homes that do not meet the energy budget must pay a fee to the Renewable Energy Mitigation Program. The $1.7 million collected in its first three years has been channeled into projects that offset greenhouse gas emissions, ranging from car-sharing commuting programs to an energy-efficient revamp of a local ice rink and providing solar hot water heaters in affordable housing.”

At first glance, that sounds encouraging. In fact, I read the email to several of my friends (without commentary) and each one of them nodded vaguely and said, “Well, they’re trying at least.”

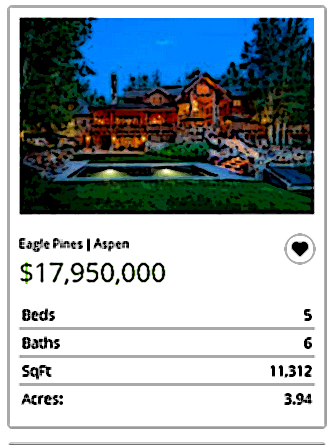

Maybe. You have to dig deep to recognize the absurdity in all this. Pitkin County, Colorado is the home county of Aspen, Colorado—-one of the wealthiest communities in the United States. It has been called the town “where the billionaires are running the millionaires out of the valley.” Do these people or its government truly deserve a pat on the back? Who can better afford to employ the latest energy-saving technologies than these guys? But what’s more important is noting the restrictions that were NOT imposed on the new home builders. Specifically—

Did anyone think to limit the number of square feet on new home or re-model constructions?

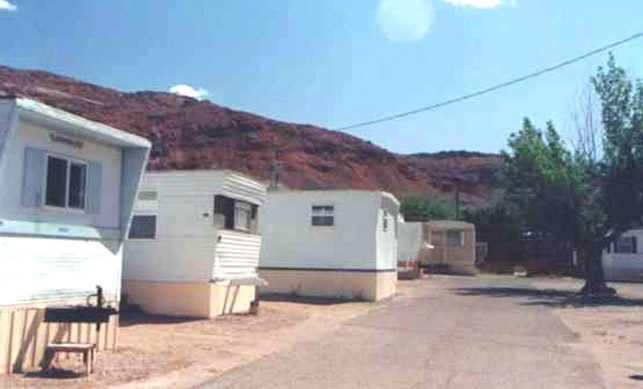

Probably not. I doubt if it even occurred to anyone on the Pitkin County Commission. But it didn’t take me long to calculate that a wealthy Aspenite living in a 15,000 square foot bunker/home and using the mandated 40,000 BTUs of energy per square foot limit will consume 600,000,000 BTUs while a redneck tool pusher living in a less efficient 2000 square foot double-wide can expect to use far less energy—-about 126,000,000 BTUs.

And it’s a safe bet that this “redneck” lives in his drafty trailer twelve months a year, while many of the energy-efficient Aspenites spend a fraction of their time there. How can we offer praise to some extravagantly consumptive part-time homeowner? Imagine how much energy it took to construct a castle like that. Consider the natural materials, the cost to operate the heavy equipment, the energy to transport the workers to the job site (it’s doubtful that any of the contractors could afford to even live near Aspen). The mind boggles.

Still, Lance Christie’s praise for Pitkin County was sincere and well-intentioned and I respect him for that, and many, if not a majority, of environmentalists probably share his enthusiasm. I’m not one of them…I can find no reason to celebrate or conclude, based on examples like this, that we’re somehow becoming a more energy-aware, environmentally conscientious nation. In fact, I think this kind of misplaced optimism does us harm.

And what about the land upon which these homes are built? Almost always, in the small towns of the Rural West, new residential developments are built on what was agricultural or grazing land. Once again the “cows versus condos” debate raises its persistent head. No environmentalist, worth his organically-grown natural sea salt, has much patience for the West’s cattle industry and especially public lands grazing. And the damage caused by some ranchers is well-documented and disgraceful.

But while some environmentalists may believe that paving over alfalfa fields with something like Moab’s Rim Village/condo city is striking a blow for Mother Nature and the New Economy of the West, we should remember Thomas Power’s warning about the long-term view of this kind of development. Runaway tourism/growth/expansion of towns like Moab should cause all of us to take notice and give pause—to re-think all of this. Exploding tourist numbers and a ‘second home culture’ transform a community, shift the emphasis of the town away from the people who live there and toward those who don’t. Moab doesn’t exist for its citizens; it’s there, in fact, for high dollar transients. And it rarely benefits the small-town residents that were there during the tough times; it’s the new arrivals with the capital to invest that flourish.

As much of Spanish Valley’s laid-back mish-mash of fields and pastures, junk cars and funky homes yield to a sea of condo developments and faux adobe second homes, who can suggest that Rim Village is more aesthetically pleasing to the eye than the alfalfa field it replaced?

And out of that shift comes a vital question for all environmentalists. When we talk about highest and best use of a piece of land, just what exactly do we mean, particularly when it comes to water and farmland? Often it comes down to a fight about cows.

I’ve always had a love/hate relationship with cows. I’ve cursed them loudly and with extreme prejudice when they turned my favorite mountain meadow, Nasty Flat, into a barren cow-pie strewn wasteland–a devastating scene perhaps more worthy of the place name.

But then…they do taste very good.

On many an occasion I’ve inched my way through a herd of these dull-witted beasts on some highway as their cowboy masters move them to summer range or winter range or to the feedlot and I wonder if I could ever grow accustomed to a steady stream of green, smelly, fly-infested shit running down my flanks.

But then…have you ever seen lovelier eyelashes than those adorning a Hereford cow? If any of my ex-girlfriends had been able (or willing) to bat eyelashes like that at me, who knows where those relationships might have gone?

When I see a herd of those heavy-set ungulates trampling yet another field or meadow, I am appalled at the damage.

But then…when I see yet another overgrazed field turned into a condo development, I ask myself—is a burned out meadow as bad as this? And when I see that same herd of Black Angus or Herefords, I also am struck with an instantaneous case of Bovolexia, an illness that actually brings me pleasure and satisfaction, and a sense of communication with these dumb animals.

Bovolexia is an irresistible urge to moo when you see cows in a field. Without fail, as I drive along some rural highway, the sight of a cow forces me to roll down my window, hang my head into the wind and moo as convincingly as I know how to. Sometimes I moo forcefully and lustily with a bullish spirit; other times my moos are wistful and melancholy, as a poor steer might feel as he/it looks at all those heifers and wonders why he isn’t interested.

But when they respond to my call and look up and acknowledge my moos, it pleases me somehow.

I can lose patience with ranchers who abuse and destroy the very land they make a living from, but I’m careful not to paint all ranchers with the same broad stroke. Ranchers run the spectrum like everyone else. If someone, for instance, tried to tell me that rancher Heidi Redd didn’t understand the heart and soul of the American West, I’d punch them in the nose. Heidi has lived most of a life at Dugout Ranch in San Juan County, Utah and I’m glad she’s there.

And so, I face the issue with mixed feelings. I’ve been told repeatedly that cows are destroying the West; yet my heart doesn’t seem to be totally committed to getting rid of them. I’ve been reminded that the Cowboy Myth is just that, but then I wonder, what’s wrong with a myth? Isn’t that what we need more of these days? What is it with this cynical 21st Century culture of ours that makes us want to tear our myths and heroes apart? I’m not ready to abandon Gene Autrey and Roy Rogers…not quite yet. Please.

But beyond my irrational defense of the cowboy and his cow, I also find a more practical side to my emotions. It’s the reality of a commodity-driven society and economy, where everything must have a dollar value, where everything must be marketed and sold and everything must show a comfortable profit.

Back in “the good old days,” twenty years ago, we didn’t give much thought to the ranchers, or to the communities that were built upon ranching, or what would happen to the ranches themselves—the old homes and barns tucked under century-old cottonwood trees, the alfalfa fields in the valleys that are as much a part of the Western landscape as the mountains that often rise above them.

Environmentalists didn’t consider then, and many don’t care now, what the fate of the Rural West might be if public lands ranching was to be eliminated. In fact, for many urban enviros, eliminating the Rural West is really a key strategy, in their minds, to preserving it.

One morning a few summers ago, a friend and I were discussing the fires sweeping the West. The conversation turned to water and my friend, the owner of a recreation-based company, complained bitterly about the amount of water devoted to agriculture in Colorado.

“Did you know,” he asked bitterly, “that 80% of the water in Colorado is used for agriculture? Yet farming and ranching only constitute 14% of the economy?” (my numbers are estimates–I can’t recall the precise figure but that’s close)

A decade ago, I might have nodded sympathetically and joined the chorus of dissent. But instead I said, “So what?”

“So what?” he growled in disbelief. “What are you talking about? You think it’s GOOD that farmers use so much water?

“Well what would you prefer?” I answered. “Consider the agricultural lands in many of the valleys in Colorado. Would you rather see them save the water for human consumption and encourage 50,000 people to move into the area? If you shut down the farms, surely there will be plenty of water for massive urban expansion.”

“No,” he replied. “I don’t want that either.”

I shook my head. “Well, it’s going to be one or the other. As B. Traven once said, ‘This is the real world, muchacho, and we are all in it.’ Do you think they’ll just let the water flow slowly to the sea? This is America, pal. Somebody’s going to make money off that water.”

So this is a question about highest and best use of the land that all environmentalists need to answer. Imagine there is a 100 acre alfalfa field that requires 100,000 gallons of water a week to produce a healthy crop. But what if a condominium complex of 300 units could be built on that same 100 acres and the water use by all those new condo residents could be cut by as much as 75%. Would the new construction represent a “higher and better use of the land” because it used less water? It’s a question we all need to consider.

I still understand the points made by “cow-free” advocates. I still recognize the damage caused by reckless grazing practices. I know changes need to be made. But at a time when the “amenities economy” is rapidly creating an entirely new threat to the beauty and solitude and health of the American West, a “cow-free” West as an end-all solution to resource degradation is foolish and simplistic. Never underestimate the greed of American Entrepreneurialism. Marketing Beauty is a brand new industry that may one day make us all long for a chance to demonstrate our Bovolexia, and there won’t be a cow in sight to satisfy us.

2024 UPDATE: THE ARRIVAL OF THE MEGA-BILLIONAIRES: I had just finished the draft for Brave New West, when I became aware of the Big Money that was suddenly powering many “grass roots” environmental organizations. In fact, the numbers were staggering. For decades, environmentalists had portrayed themselves as the underdogs, fighting a cash rich extraction industry. But it simply wasn’t and isn’t true. For twenty years, the environmental movement has embraced big Money, wherever they can get it. From the Industrial Recreation Industry to Mega-Billionaire venture capitalists to the world’s most noted financiers and bankers. Here are a couple Zephyr stories (they’re long) that came to light after Brave New West was published. Here and Here

*****

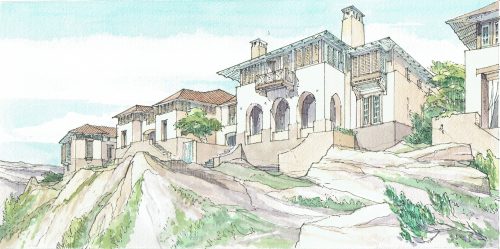

In the not too distant past, cows roamed Johnson’s Up on Top, a mesa just south of Moab, for winter grazing. But a grandiose “amenities” project called “Cloudrock Resort Development” will someday exile the cows yet again. And again we’ll long for our bovine friends.

Cloudrock was first introduced to Moab citizens in 2000, after months of secret negotiations by the developer, the State Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA) and local elected officials. SITLA lands are state-owned sections that were created to generate income for Utah schools. If you look at a state map, you’ll notice a checker-board pattern of squares dispersed across the state. Those are SITLA lands and are often land-locked—-surrounded by federal BLM land and National Parks. For years Utah legislators have sought ways to exploit their holdings, but Utah was until recently “old school” in its thinking. Development of SITLA land meant cattle grazing or more often, mining and drilling. This is where they figured the money was.

But a decade ago, it occurred to the SITLA czars that state lands surrounding New West towns like Moab had a value they hadn’t considered. Since then, the State of Utah has negotiated with the federal government to swap many of its scattered and isolated state lands for clusters of state sections. Sometimes the clusters are based on their mining potential, but lately SITLA has sought lands near booming towns like Moab. The implications for the future are staggering. In the rural parts of most Western states, private land is limited. Rural towns are often like small islands in a sea of public domain. The opportunity for sprawl faced physical limitations. The SITLA land swaps changed that in Utah.

Cloudrock, as originally proposed, called for three luxury lodges with 198 rooms, 50 condos and 75 homesites—-lots would start at $600,000. According to the Cloudrock Development Proposal, assembled by the project coordinator Michael Liss and obtained by The Zephyr in 2000, the plan was stunning. It reported:

“Our intention is to create a world-class wilderness destination resort community in the American Southwest for people who enjoy the beauty and cultural legacy of the region. The centerpiece of this community is the Cloudrock Desert Lodge, an intimate luxury wilderness lodge that will set the tone and standard for the entire community…We expect our guests to return time and time again, finally deciding that this is where they want to build a second or third home…We plan to spend the time, money and creative energy necessary to create a real estate development that will deliver top prices.“

As to who might be a candidate for a Cloudrock future, the proposal could not be clearer:

“We will use a highly-targeted approach, planning intimate get-togethers at the homes of our friends and initial clients, as many second home real estate purchasers are often as interested in who their eventual neighbors might be as in the property itself.”

It really said that. And to add insult to injury to anyone with a net worth less than $10 million, the marketing plan promised that:

Johnson’s Up on Top will be marketed as a vacation community for affluent families and individuals. The Moab real estate market does not currently serve this segment well, with most developments targeted to a somewhat lower economic bracket….the lodge and condominium units that will comprise this mesa village will form a dense complex in the spirit of the Italian hill towns like Siena and San Gimignano…The Phase III condominiums will be built in the spirit of the Anasazi Cliff Dwellings of Mesa Verde.

Clearly, Cloudrock was selling itself to the wealthy, but more specifically to high-end visitors and future home buyers who also considered themselves environmentalists. Liss was quick to point out the easy access to national parks and wilderness areas, some adjacent to Cloudrock itself.

There was a time when the environmental community might have been appalled by such an extravagant scheme. After all, the conservation movement is rooted in the word “conserve.” How could such an opulent, consumptive and arrogant plan even dream of winning the acceptance of environmentalists? In the Amenities Economy, anything is possible.

As the Cloudrock development became better known and was required to submit itself to governmental and public scrutiny, the Glen Canyon Group of the Sierra Club weighed in on the issue. On behalf of the group, Jean Binyon addressed its concerns to Michael Liss in a February 2001 letter. Binyon made it clear that, “It is our consensus that the best thing for Johnson’s is no development at all.”

Having said that, however, the Sierra Club had no intention of putting up a fight.

“We realize you are making efforts to ensure that Cloudrock meets standards above and beyond Grand County’s….We realize you are well on your way to completing the preliminary plat, and incorporating changes becomes more difficult with the passage of time. Never the less, we hope you will be receptive to our concerns…”

What kind of concerns did the Sierra Club have and what were their requests? Besides setting structures farther back from the rim of the canyon, Binyon made the following demands:

“Coloring roads to match the surrounding soil…parking lots colored to match the surrounding soil…utilizing medium to darker earth-tones, and non-reflective materials on all structures…outdoor lighting should be kept to a minimum…”

They were literally cosmetic in nature.

The Sierra Club also encouraged restrictions on OHVs…”Next to cows, (this is) the most damaging thing currently happening on the mesa. Please be explicit in not permitting their use on the mesa.”

Apparently, keeping out cows and OHVs was an acceptable trade-off for a massive multi-million dollar “wilderness” resort lodge and scores of condos and homes built on $600,000 lots.

Liss’s reply could not have been more accommodating, “I would be happy to discuss our project with you and members of your Chapter,” and added enthusiastically, “I am a member of the Sierra Club and greatly respect the work being done around the country.” No other environmental group in Utah even chose to express an opinion.

2024 CLOUDROCK UPDATE: Cloudrock, as it was originally proposed, never happened. The Great Recession of 2008/09 played a major role, and economic realities deterred the project. But as Lance Christie noted, before his death in 2010, ultimately Cloudrock succeeded. Christie observed that in the years immediately following the introduction of Cloudrock, with its insane prices, Grand County’s real estate market seemed to take the idea of a high end residential community and ran with it. Between 2001 and 2007, residential prices more than doubled. I know that for a fact. Suddenly my little 900 square foot home was “worth” a quarter of a million dollars. Just a few years earlier, I had joked with my favorite realtor, Norma Nunn, about selling my house. And I had even thrown out the 250K price as a teaser. Norma just laughed…”Check back with me in 25 years.” It happened in less than five.

Since then, what has happened to Moab defies all logic. But it’s nothing but a cash cow for investors who arrived in Moab with far more money than a a genuine interest in the future of Moab’s working class residents. I see no change in the direction Moab continues to follow, despite the well-meaning intentions of new Moabites who arrived about 30 years too late. And are now upset about it… JS Feb 21, 2024.

How could any environmental group be so passive or silent in the face of a project that was so contrary to the basic principles of conservation? These homes, whether they were constructed with the most energy-efficient, recyclable technology available, would be massive consumers of natural resources, would be clearly visible from Arches National Park and other scenic areas, would actually be constructed adjacent to proposed wilderness and would play havoc with the social fabric of nearby Moab by driving property values and taxes even higher. To recall Thomas Power’s warning again:

“...ongoing economic growth may well threaten the ecological integrity of wildlands as growing population, human settlement, and commercial activities and their accompanying pollutants isolate and disrupt natural areas.”

How can environmentalists sit idly by? Because they can’t oppose the very economic strategy for the Rural West that they have embraced philosophically for years. And especially because they fear the risk of biting the hands (and dollars) that feed them. In the battle for wilderness in Utah, fundraising plays a greater role with each successive session of the U.S. Congress, as wilderness advocates push for permanent legislation. Money is everything. Or as Chris Peterson, the 28 year old former Executive Director of the Glen Canyon Institute put it:

“It is felt that without playing the game on their opponents’ terms, they don’t stand a chance. So is it better to win or lose the fight? Those with experience in the field of environmental advocacy deem it necessary to play ‘dirty’ and enlist any and all means necessary to accomplish their goals, and believe that walking the alternative ‘high road’ is an exercise in futility and ultimately leads to failure.”

How much “dirt” are environmentalists willing to endure? Try this on for size…

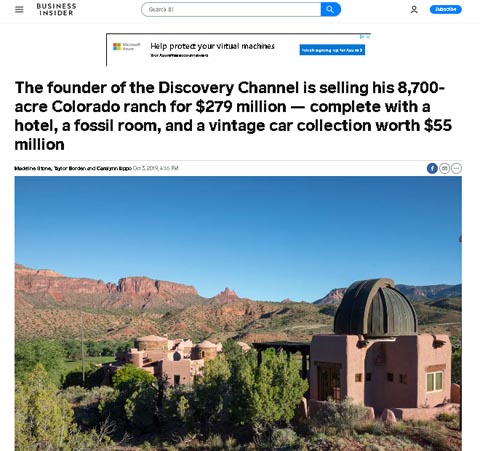

John Hendricks is the CEO of cable television’s Discovery Channel. He says he has passionately loved the West since he was a kid when his father told him that the most beautiful place on earth was a seldom-visited redrock paradise called Gateway, Colorado. A few decades later, John Hendricks bought it–lock, stock, and barrel. John Hendricks is rich. His attorneys made offers to local landowners that were hard to resist and by 2002, he had accumulated more than 6000 acres of property, some of which he intends to put into conservation easements. Hendricks also decided to build himself a home where he could survey his holdings. At last report the Hendricks home has just enough space for John and his wife to feel cozy–about 27,000 square feet. It was reported to be the largest residential construction project in America a few years ago. Now he’s added a massive lodge and restaurant, a vintage car museum and turned a once quiet backwater into what he hopes will be a booming business. All this so he can “save” Gateway, Colorado.

The John Hendricks project is perhaps the most grandiose acquisition and construction in a frenzy of western land buying by America’s wealthy and elite in the last decade. It is becoming a familiar sight—-mansions and castles perched on the brink of some mesa rim or canyon, or mountain side, staring down at the little people.

An acquaintance of mine, the leader of an environmental group in Western Colorado, and I were lamenting the mega-homes and mansions being built everywhere in Colorado, from the Front Range to Glade Park and eventually, Gateway came to mind…

“What about this John Hendricks guy and his castle at Gateway,” I said. “He’s got to be the most extravagant of them all.”

There was a long silence on the other end of the line.

“Uh…I think Hendricks is trying to do the right thing,” he said softly.

I paused briefly…

“So how much money does he give your organization?”

Another brief pause. “A lot.”

People like John Hendricks have found an age-old way of gaining respectability and even adoration; they simply buy it…they buy everyone. His contributions to ‘worthy causes’ are significant. He has kept a few artists eating well and contractors love him. Maybe the Second Feudal Society is our only option, where the peasants and serfs wait and hope for their wealthy masters to sustain them. And hope that their masters are the benevolent type.

2024 GATEWAY UPDATE

Environmental organizations have certainly benefited from large contributions. Consider SUWA’s financial status. For years, it was the scrappy underdog, one more struggling environmental group, trying to survive against the powerful ranching, mining and ATV lobbies in Washington, D.C. And it was supposed to be like that.

In a 1999 story for the Zephyr, current SUWA executive director Scott Groene wrote in praise of his former boss, environmental legend, Brant Calkin:

“Brant offered his staff low pay but lots of autonomy to ‘do good and fight evil. The benefit of lousy pay is you get to experiment.’ Calkin offered low wages because no environmentalist should be in it for the money, and ‘pay doesn’t affect the quality of the staff.’ He offers as rationale both that environmentalists have an obligation to spend their members’ money wisely, and that small salaries ensure that only the passionate keep their jobs. He adds that while experience is useful, it doesn’t automatically result in better or smarter actions: ‘smart young people with fresh ideas are just as important as those who have been around the track a couple of times.’”

Groene continued:

“Brant never asked his staff to do anything he wasn’t already doing. For example, he and Susan Tixier earned a total annual salary of $20,000 between the two of them as Director and Associate Director, about a third of what the current SUWA director makes now (in 1999). Brant never stopped working, whether it was leading the Utah Wilderness Coalition out of shaky consensus efforts, hustling money, or fixing a fleet of beater SUWA cars (he was renowned for resurrecting aging office equipment and trucks). And when it seemed everything was done, he’d start cleaning the office. “

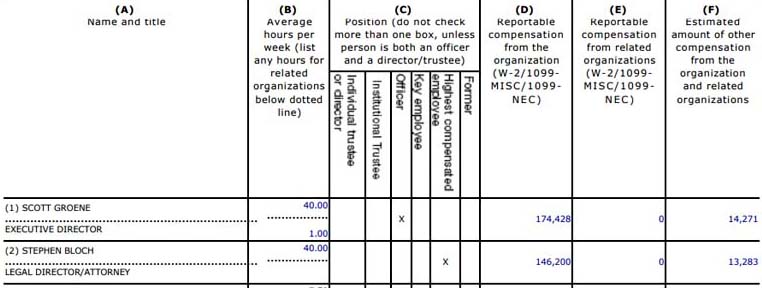

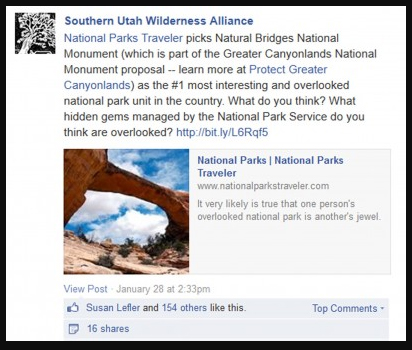

But in 2005, SUWA is awash in money. Its 2004 “Form 990″ report, available to anyone who requests it because of SUWA’s non-profit status, shows the organization had net assets or fund balances worth $4,777,352 at the end of 2004, up significantly–$1,128,211–from the previous year. Salaries and benefits exceeded a million dollars. Its executive director earned an income of $70,775 in salary and benefits. SUWA even has a mutual fund and stock investments worth $894,986. SUWA recently purchased a grand old home in downtown Salt Lake City for $800,000 as its new headquarters and spent another half million dollars renovating it; clearly the need for legends like Brant Calkin to ”renovate aging office equipment” has passed. The idea almost seems quaint. While many non-profits invest their revenues in such ventures, it probably rarely occurs to most grass roots environmentalist contributors that their membership dues might end up on Wall Street or in real estate.

NOTE: In 2006, I wrote a short piece for High Country News called “SUWA Can You Spare Dime?” It can be found here.

SUWA’s counterpoint in the wilderness world, especially when it comes to road and trail access on public lands in the west, is the Blue Ribbon Coalition, headquartered in Pocatello, Idaho. The BRC has been a voracious advocate of ATVs and other forms of motorized recreation and most grass roots environmentalists would assume that the powerful motorized recreation lobby gives them the edge in fundraising. Yet a comparison of the two organizations’ Form 990s shows otherwise. SUWA outspent BRC by more than $1,500,000 in 2003. And while BRC operated at a loss that year, SUWA increased its net assets by almost $600,000. BRC’s net assets at the end of 2003 were a paltry $59,100. I don’t suggest here that pro-motorized recreation deserves more funding by any means. And perhaps the funding gap can be attributed to a land ethic that is moving away from motorized recreation. But the notion that environmentalists like SUWA are the economic underdogs—-the David to BRC’s Goliath—-is pure myth.

In the end, money ultimately doesn’t seem to be swaying anyone in the decades long fight for wilderness. Ten years ago, SUWA’s staff was half the size it is now. Its starting salaries, in keeping with Brant Calkin’s admonition, were about $16,000. Now, with more money than they can even hope to spend, SUWA and the Utah Wilderness Coalition is no closer to passage of a state-wide wilderness bill than it was then. In fact, while its assets have grown dramatically, its membership rolls have dropped significantly. According to a SUWA source, membership has fallen “from 21,000 in 1995 to around

2024 SUWA MEMBERSHIP UPDATE

The advent of social media in the last ten years has been a boon to environmental groups like SUWA and its numbers have exploded, especially when it can boast a media budget alone of over $2 million.

There are voices of dissent as environmentalism falls further away from its ethical roots. A letter to “The Public Forum” in the The Salt Lake Tribune caught my eye not long ago. It was a letter from David Jorgensen of Salt Lake City about environmental ethics. “It is unfortunate,” he wrote, “that wilderness advocates must resort to economic arguments as part of their advocacy. There are some areas that…should be left alone for their own intrinsic worth and not just for human economics or even human enjoyment.”

But in the same issue, page one, another article only confirmed Jorgensen’s fears about the future of the environmental movement. The headline read, “Outdoor Group Threatens to Leave Utah Over Land Deal.” In response to a disastrous plan by Interior Secretary Gale Norton to cut millions of acres of BLM wilderness from Utah, and with the support and blessing of Governor Leavitt, enviropreneur Peter Metcalfe threatened to move his Outdoor Retailer trade show, worth $24 million to the state’s economy, somewhere else.

Suddenly, Leavitt was in a panic and quickly scheduled a meeting with Metcalfe and other outdoor industry representatives, “in hopes of,” according to The Tribune, “selling them on his environmental bona fides.” It was clear who had become the most powerful environmental lobby in Utah. It wasn’t the Sierra Club. It wasn’t SUWA. It was the Outdoor Retailers Association.

“Selling” was the key word here. All the intrinsic reasons for wilderness are being trampled in the hard-sell, not just by the people who oppose wilderness, but by those who support it as well. All the eloquence of John Muir and David Brower and Wallace Stegner and Ed Abbey, among many others, couldn’t move hearts and minds to pass a decent wilderness bill. But the suggestion that eloquence and values and integrity have given way to trade show boycotts, the commodification of Nature and the marketing of beauty as our most powerful tools for wilderness preservation somehow fouls the very meaning of wilderness itself. The Outdoor Industry needs a pristine wilderness to make money, so what better reason to preserve it? For the environmental community to embrace, or even cast a blind eye toward that philosophy is more than many can bear.

At the core of the environmental movement has always been the belief that its constituents must adhere to the ethics and values that make them environmentalists in the first place. It’s much easier to be a consumer than a conservationist. From the beginning, we’ve embraced the idea of living a simpler life. Of leaving a much smaller footprint on this trampled old planet of ours. Of honoring and respecting the natural world. Of even making a sacrifice in order to assure that some part of our earth is left unscathed by the Works of Man. Our purpose and our goal has always been to pay tribute to The Land itself.

But how can environmentalists escape the label of hypocrisy? How can we condemn oil exploration when our own consumption of oil is staggering? How can we condemn the impacts of motorized recreation while we turn a blind eye to the damage caused by ever-growing numbers of non-motorized recreationists? How can we heed Abbey’s warning of Industrial Tourism when, at its heart, that kind of economy is the future many enviros have embraced for 15 years? How can we condemn the timber industry when we continue to build homes at an alarming rate that encroach on the habitat of the very wildlife we want to protect and then construct them far bigger than anything we’d ever need to be happy? And when some of our biggest environmental contributors consume massive amounts of natural resources to build monstrous part-time homes, how can we possibly accept their donations?

Like a civil rights organization in the 1960s accepting money from a man who belonged to an all white country club, these are the contradictions that destroy our credibility. And like the Civil Rights Movement of 40 years ago, saving what’s left of the wild American West is a moral issue, first and foremost. We didn’t fight for the rights of African-American men and women because there was a dollar to be made. Nor should that be our motivation as environmentalists to save wilderness. If we continue to follow this dangerous path, we may someday wonder if the Road to Victory was worth it.

Or wonder what it is we actually “won.”

SELECTED READING RELATED TO THIS STORY:

The Greening of Wilderne$$: How the Mega-Rich Are Co-Opting Environmentalism and Turning It Into a Big Business — Jim Stiles

Selling Wilderness Like used Buick: 1998. When Everything Changed —Jim Stiles

Designate it. Publicize it. And They Will Come and Destroy It. Of Untouchable Rhetoric and the Fight Against Overvcrowded Tourism” Bill Keshlear

The New West Progressive Paradox: Can Liberal Greens Still Possess an Honest Conscience in the New West? —Jim Stiles

Why Crowds, Chaos and the Loss of Solitude Don’t Matter in the New West — Jim Stiles

Unsettled America: The Divisive Environmentalism of The Recreation-Industrial Complex —Stacy Young

The Slovenly Wilderness: Anatomy of a Zoom Town —-Stacy Young

Sustainable Moab: A Reality Check — Jim Stiles

MOAB Greens Confess: “INDUSTRIAL TOURISM EXISTS!” (and now their solutions.) —Jim Stiles

*****

Jim Stiles is the publisher and editor of The Zephyr. Still “hopelessly clinging to the past since 1989.” Though he spent 40 years living in the canyon country of southeast Utah, Stiles now resides with two cats, Rambo & Rascal, on the Great Plains. Coldwater, Kansas is a tiny farm and ranch community, where there are no tourists.

He can be reached via facebook. Messenger, or by email: cczephyr@gmail.com

To comment on this story and offer your own opinions on the subject of “The Amenities Economy” & “Industrial Tourism,” please scroll to the bottom of this page. I welcome thoughtful, constructive criticism. But PLEASE, no personal epithets or insults to ANYONE…Thanks…JS

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

$55 Each or Two for $100 (Free Shipping.)

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

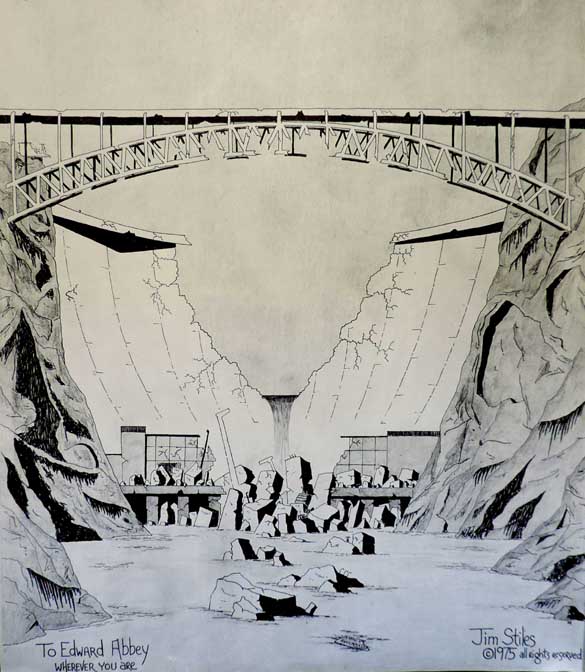

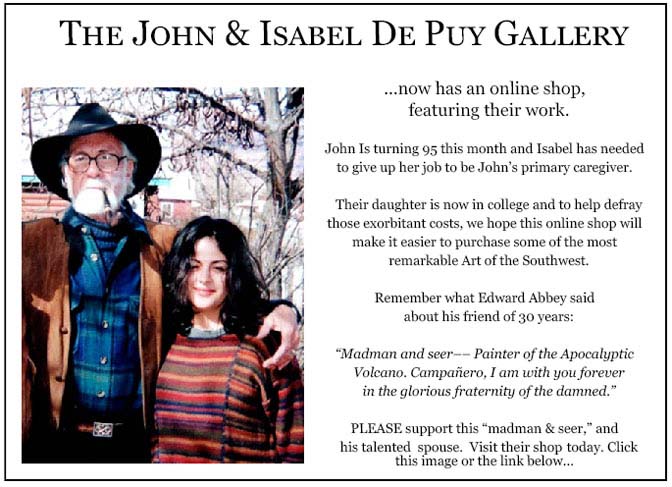

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

Quite the rant Jim. I think a corollary to “Build it and they will come” is “Advertise it and they will buy.” When I was Rangering in Needles back in ’80 I encountered a jeeper in Davis Canyon looking for a particular pictograph. I could see a copy of Outside magazine on the console open to a page with a photo and blurb about the area. I cried inside. The word was out and the hordes would come. Coinciding with this was Reagan’s embrace of Friedman economics. Remember that guy, the Nobel laureate promoting free-market capitalism and monetarism? Moab, Tehelluride, Aspen, Ketchum, Jackson, … formerly little ranching towns co-opted by the wealthy as part of their image. Money follows money. It wasn’t just the tree-hugging backpackers that altered them, it was big money. The environmentalists and recreationists were pockets to pick. There is an article out today about home energy restrictions, but no footage restrictions in Germany. You don’t make much progress riding a horse on a carousel. It is a universal issue, not unique to the wild west. As for the water, no I don’t want to see it siphoned off for a development designed to fund some fat cat’s mega-yacht. But I also don’t want to see it growing alfalfa for a Saudi Prince’s horse stable, or for a Bundyites arsenal and big rig. It belongs in the river, what’s left of it.

I wonder where all the national outrage was when we lost all the orchards in Moab to housing development in the 90’s, and none of it for affordable housing? The outrage we see now with the proposed development at the old egg ranch doesn’t even know that Moab was well on its way to what it is today long before this new professional class of non-profit activists moved in and decided to make their home in Moab. And of course, none of them will acknowledge or admit the role SUWA played in transforming Moab into the one trick “amenities” economy we see today. Now they want to blame it all on outside “billionaires”, oblivious to the role outside billionaires played in the building of SUWA and the selling of this snake oil “amenities only” economy to the local population. Now they want that gone too……

It is articles like this that made me a follower of yours Jim. 1000% agreement.

Moab-no longer Moab. National Geographic, I think, lauded the use of dirt bikes way back. Many other depredations before and since.

Moo! “In individuals insanity is rare, but in groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule” (Nietzsche). Thus explains your royal “we” and what “we” as a society have done to ourselves. For me, the real question is how to communicate this to the non-believers? You know how difficult it is to get anything published other than optimistic pollyanna hope-for-the-best-of-everything claptrap. Trust in the Technological Cornucopia! More people can only mean More Better! As part of your choir, I take your preaching to heart. “We” are but voices in the wilderness, to paraphrase Mr. Abbey.

The Almighty Dollar! We used to use a shortcut to LA called the Devore Cutoff, lined with beautiful orchards. They’re all gone. I grew up in a town where we could sit on the curb early mornings to catch a ride with a schoolmate (high school) whose job it was before school to go the Union Pacific Railroad housing and awaken the train crews for the days’ journey. There were numerous flowing wells around the area, one still in the forties, where one could take bottles and fill them with clear, safe water at no cost. Walking down the main drag took a long time because you knew almost everybody you met. Homes were left unlocked, also cars, and neighbors often entered, left a note saying what they’d borrowed. That area now is closing in on 3 million residents! Crime has risen. Almost a murder a night. Recreation areas are overwhelmed. Our natural water sources, aided by a man made lake, are in danger!

Hi Donna…Jeez, the “Devore Cutoff””. How many decades since I’ve heard that phrase! I grew up in Pomona; I suspect you’re from around there too.

Here’s the problem as I see it.. Beautiful, desirable places where people obviously want to be carry the seed of their own destruction. Southern California was once close to earthly paradise; look at it now. Ditto Jackson, Moab, the Summit County metroplex (Breckenridge/Frisco/Silverthorne/Keystone) in Colorado (and the growing Eagle County metroplex along I-70)……No offense, but I don’t think North Dakopta or Mississippi have these problems.

Er..I meant North DAKOTA.

Thanks, Jim. I have also been watching Moab, and much of the West, undergo change since the 1970s. And I don’t like much of what I have seen.

But judging others by what I like or don’t like is a dangerous temptation. We humans tend to gather in tribes that share common values and beliefs, and then get busy condemning others and their beliefs. And then we might get motivated and either try to convert others or banish them, if not physically then at least from control.

And it always comes down to control. How else can we make our visions real?

Who should control the land, especially public land? All of the public? Only the influential (e.g the wealthy)? Or maybe only those we consider enlightened? Does a small portion of the public have any moral claim to control more than “their share”? I will risk projecting, and think that most activists do interpret their superior morality into a mandate to make all decisions.

Speaking of the real world, the US population has doubled since I was born. The population of Utah has tripled, as has Colorado (almost), while Arizona has 6 times the people. And I will speculate that the percentages of people who frequently play in the wild lands has also dramatically increased.

So what would you rather have? Moab in the early 1900s as a tiny rustic farming and ranching community, without a Hampton Inn or IPA in sight? (and also no vegan food coop). Moab in mid-century, industrialized as a small town can be, and a center for the uranium boom? Maybe the 70s, in transition from nowhere to somewhere, but mostly a cheap place to live (but also a cheap place to work)? Or anytime since the dawn of this century, all mid-scale and up-scale and mostly dedicated to tourism?

I have no answers, only preferences. And again, I hesitate to claim that my preferences are superior for anyone but me.

Bob Krantz, I like your commentary. And I, too, live in a city (Bend, Oregon) where much the same phenomena are occurring, albeit there are differences when compared to Moab, Aspen, et. al. I wonder if Moab and Aspen have the same unhoused community issues that Bend has.

But there is an old adage that “nothing is as constant as change itself.” I cherish my memory of the the Moab I first visited in June, 1970, when Bates Wilson shook my hand, welcomed me to my first job as a seasonal ranger at Natural Bridges, and remarked jokingly that this is a lot different than California. I replied that “the air is cleaner here”; Bates and his Chief Ranger both laughingly agreed.

Yes, Moab, Bend, and the like have become the scene of the ubiquitous trophy homes, and the Blandings, Escalantes, and Burns (in my area) haven’t, at least yet. Forums like the Zephyr (thanks, Jim), help us remember these “good old days” while we are still alive, and a few of our children may help preserve the sense of the mystery of our history. My son is one of them.

Two other perspectives: 1. What did this landscape look like 100,000 years ago? Now go forward 100,000 years; it may again be very different. 2. On the discussion of the seemingly bucolic scenes of cows and cowboys, exemplified so well in our images of the American West, yes, I too appreciate those images. I’ve attended the Cowboy Poetry gathering in Elko, NV for decades! But how do I reconcile this with my commitment to a vegetarian-mostly vegan diet and believe we humans would be much better stewards of the finite nature of our planetary home if we all adopted such a diet? Honestly, it’s inconsistent, if not hypocritical.

Like you, Bob, I don’t have answers, but do have preferences.

One of my favorite subjects to bone up on is the sense of place—or the lack of it. So many great writers touch on the topic.

I’ve never been able to develop a sense of place, because, with humans involved, a place *always* changes, whether it’s a small town-cum-large (ala Moab, Bend, Boulder, Flagstaff, etc.) or the emptiness of an ostensible nature plot about to be developed or cordoned off as “wild.” The human plague expands and migrates. The population counter on this site is sad evidence of the explosion. I’m beginning to think World War III might be a good thing. How messed up is that?

Sadly, I’ve given up on ever finding a sense of place. Or a sense of peace. Adapting to a plague seems wrong. What did the philosopher say? That it’s no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society?

It seems we can compare society/civilization to individuals with cancer in its embryonic stages—it doesn’t even know it’s unwell. Only a relative few of us can see it. But there is no cure.

I always found it interesting when someone would move to a place I was leaving (running from) and he’d say something to the effect of, “how great this place/town/city is.” Change and destruction and growth seem inevitable; it is perspective—and hope—that is destroying me.

I was foisted into the ancient vocation of societal cast offs(Han Shan, Thoreau, Everett Ruess, Japhy Ryder,..) a rucksack revolutionary, Dharma Bum at the tender age of twenty, after tending to, with mother and sisters, my father’s(age 56) agonizing cancerous demise on a rented hospital bed in our suburban homes “living room”. Fourty plus years later, my mother(age 86), and a little over a year ago, my sister(age 64); all eatin up by the insatiable hungering’s of cancer. So yeah, like so many countless others, the remaining regions of the western wild lands have provided a restorative sanctuary for mind, body and spirit; a refuge of beauty(evolved ecological energetic elegance) and sanity from the insatiable ravaging’s of the Hungry Ghost economy. Forums like Canyon Country Zephyr, maintained by the lovingly, diligent tenacity of Jim Stiles; provide a gathering place for all those traumatized by and despairing the accelerating desecration of the Sacred Web of Life. I’ve recently been on a bender of listening to interviews on the overpopulation podcast; Christopher Ketcham(the Megamachine and green growth delusions), William Rees(confronting overshoot: changing the story of human exceptionalism), Dr. Paul Ehrlich( sawing off the limb on which we are perched). “The rising hills, the slopes of statistics lie before us. The steep climb of everything, going up, up, as we all go down. In the next century or the one beyond that, they say, are valleys, pastures, we can meet there in peace, if we make it. To climb these coming crests, one word to you, to you and your children: stay together, learn the flowers, go light.” For The Children, by Gary Snyder, wise elder on Turtle Island.

Agree or disagree, these articles always help to me think a little deeper. And from the comments above, that appears to be true for many of us.

I am one of those California expats – neither proud of that status nor ashamed – who has been in Utah for most of my adult life. Though I lived in SLC, I have always loved SE Utah and traveled there whenever I could. Now I live in SW Utah, homeland of the Southern Paiute. There is a photo of John Wesley Powell (usgs.gov) talking with a member of the Kaibab Band of Southern Paiute around 1870. Widening the cultural lens a little bit, maybe the early history of the New West begins in the 1870’s rather than the 1980’s.

Thanks Jim