The first time I went to Big Bend I drove all night. West of San Antonio on US 90 the land emptied into flat black space and one or two distant lights. After two hundred miles I crossed the wild old artery of the Pecos River: a strange, wide river canyon cutting at jagged angles through the moon of nowhere.

On the west bank of the Pecos River the creosote began. There were no buildings, no distant lights; through the blue hues the holy blanket of creosote appeared, spreading across the darkened horizon. This was star country, where you ride under the Spider’s mesas. Right off the bridge I could feel something prickling, something in the sky that was sentient. Unlike the morose rangelands.

I drove and drove alongside my companions, the creosote.

At 4 a.m. I slipped around the neck of Persimmon Gap onto the Chihuahuan Desert floor of Big Bend National Park. Rabbits, bugs, and birds ran, flew, buzzed, and whizzed in front of my headlights as the road slithered through the blue desert and powerful mountains began to appear darkly from the west. At Panther Junction ranger station, 30 miles in from Persimmon Gap, I stared up at mammoth purple shoulders of rock and height. Thinking, these mountains are living beings. Somehow.

Now I’m a scientifically educated person. My mother was a microbiologist and both of my parents had doctorate degrees. I’ve studied biology, chemistry, physics, geology, calculus, probability theory, and statistics. I enjoy reading science and well understand the geology of the mountains that I stood beneath.

But that’s not what I was feeling then. There’s something about being in our human environment of evolutionary adaptation, a landscape with some wildness to it, that feels different and that’s singular. When I’m in a place like that it’s almost like a current of electricity is shooting through me. Being in such places has opened up entirely new feelings and experiences, some of which have been important to me. I’ve struggled with what to call this: the enchantment of the land; the wildness of the land; the sacredness of the land.

Chief Oren Lyons, an Onondaga tribal elder, made the following comments on this subject in his keynote speech at a Native American conference on climate change, held at the National Museum of the American Indian in 2008: “How do you relate to the Earth? That’s what you have to learn; that’s what you’ve lost. You really don’t comprehend it; you don’t experience it. You intellectually understand it, but you don’t experience it. You don’t actually feel the love for the Earth, which is important for your survival.” (See the 32+ minute YouTube of his talk, listed with his name and “The Mother Earth Call to Consciousness on Climate Change.”)

So this is about love. We don’t even have a language for loving the landscape within our mainstream Western cultures, although writers like Ed Abbey and Jim Stiles have worked toward giving us one. You can find virtually no public figures representing the dominant perspectives who will even discuss our failure to love the Earth, much less the massive consequences for this failure that are sailing toward us like an oversized asteroid. There is only silence.

So I want to write about loving the earth, however awkward and seemingly unscientific my effort may be. Some words and expressions I’ve used can be seen as metaphorical or symbolic rather than literal.

I like being surrounded by creosote. I like being suffused by it and by sagebrush as well. When it stretches out to the horizon in all directions it feels like a warm blanket. At the same time it’s as though there’s a subtle electricity in the atmosphere all around, sharpening my eyesight, perking up my ears.

I have similar feelings in the desert around clusters of Soaptree yucca and Sotol, in the uplands among pinion-juniper woodlands and in stands of Ponderosa pine, and along canyons stippled with Mormon Tea, Cliffrose, and juniper.

If I spot a tiny, green insect on the inside of my windshield when I’m about to park my car, I try to flick it outside without hurting it so the heat buildup in the car won’t kill it. I’m drawn to wild flowering plants, the ones humans don’t cultivate and control: I love to stare at the little white clover blossoms or gaze at a neglected lot quilted with dandelions, and of course the Fairy Dusters and Apache Plume along trails out West. And the little circular plants that grow up through the cracks in the sidewalk.

While it’s possible to sense this kind of energy almost anywhere, I experience it as stronger, sharper, and much more pervasive – more available – in the remote areas that remain out West. Thirty years ago you could feel this at the edge of almost any Western city or town; today it takes time and energy to get far enough out from the cities and spread-out developed areas.

I sense similar pervasive energy out in the forest-covered hills and low mountains of West Virginia, but it feels weaker here. Of course this could be my own subjectivity at work; I like open Western spaces. But if my perception is accurate, I suspect a key reason is West Virginia’s much higher population density throughout its rural areas relative to the open deserts and publicly owned uplands out West. On the other hand, West Virginia may offer the pervasive energy it does because of its remarkably contiguous forest cover, which has been saved from the axe by the hilly, mountainous terrain.

I must also mention mountaintop removal coal mining, which is genocide against Appalachian mountain-beings by coal companies. It is haunting the land with sorrow.

Some landscapes, provided they haven’t been overpopulated or “developed,” seem to have a particular capacity for opening people up, assuming they go there with a receptive attitude. These landscapes may inculcate a sensitivity within people that they wouldn’t have developed elsewhere, yet once they have it they can experience it in other places. I believe that indigenous people have sent their young people to do vision quests at such sacred sites from time immemorial.

It’s where they go to bond with the land.

But the mainstream, including the worlds of business, science, religion, politics, and Lord knows economics, places no value on sacred sites as such, because it has no understanding of them, nor does seek to acquire any. It may protect some of them for ancillary reasons, such as recognizing Native American religious rights, or designating others as national monuments because of their beauty or historical relevance. But not because preserving them will help people love the land.

How has humanity fallen out of love with the Earth?

I believe the vicious cycle has worked this way. The more we overcrowd, overpopulate and develop a landscape the more insensitive we become to it. After awhile it no longer seems to give off energy; we no longer feel perked up when we’re walking through it. Our feelings of love for the land, our excitement for it as such, begin to fade. Increasingly it only seems relevant to us to the degree that it serves our needs and wishes: by farming it, mining it, drilling for fossil fuels on it, building on it, blasting through it to build highways, even by growing gardens and flowers on it, if what we’re thinking is that WE grew all that. And by “recreating” on it if there’s no feeling for solitude.

In time we cease to love the land for its own sake. We may still have sentimental, poetic moments about the beauty of trees or vacation in a national park, but our fundamental behaviors toward the land have become entrenched, based on a sense of ownership and entitlement. We rationalize this attitude either by claiming that the Earth and all creatures upon it were given to us by God to exploit however we wish or that we’re the dominant species and that we can do whatever technology and our power allow us to do. In truth we have become dependent on converting the Earth into energy, property, money and entertainment for ourselves; to feed our extravagant way of life. Instead of loving the Earth we’re devouring it.

People who deeply love the land sense the viciousness of this cycle and therefore advocate against overcrowding, overpopulation and overconsumption, which perpetuate all this. Those who only understand on an intellectual level, by contrast, tend to settle for politically convenient compromises because their hearts and guts are committed elsewhere. They are NOT horrified, for example, to discover that an isolated and once luminous, secret canyon in northern Arizona was just used as a backdrop for an antacid commercial on television and is flooded with visitors. They will regard this as a commercial phenomenon, mutter that you have to be realistic about such things, and go on with their work for the Democratic Party or a conventional environmental group.

But not Jim Stiles. Here are his comments about what happened to this canyon, which was still searing to him ten years later: “That was a decade ago. The commodification of nature was gaining strength, and not just the industrial-strength tourism that [Edward] Abbey described in 1968. This was something different, something more than obscene. It was taking the purest form of nature and bastardizing it for profit. For all of us who preferred our adventures free and unfettered, the changes in recreation were ominous.” (Brave New West, 2007, pp. 101-103).

For Stiles, the process of turning this once isolated canyon into an article of trade and a crowded tourist site was a desecration. His opposition to the commercialization of wild areas on the Colorado Plateau and to the hypocrisy of having wealthy tycoons as directors of environmental groups has made him a persona non grata to well paid, compromise-prone environmentalists in the area.

In other words, Jim Stiles loves the Earth the way Chief Lyons says the rest of us need to.

That’s why he pisses people off.

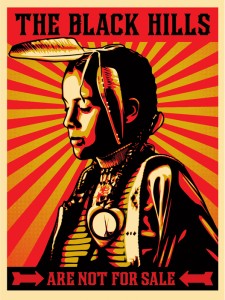

A stark depiction of our obsession with the bottom line is the planned auction of Pe’ Sla, a Sioux sacred site in the Black Hills of South Dakota. It is comprised of 1,942 acres, described as both “pristine prairie grass” and as “prime real estate.” The former by those who find delight in it and the latter by those who seek to grind money out of it.

What brought the matter to a head is this. The South Dakota Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration have been studying the feasibility of paving one of the roads running through Pe’ Sla. A paved road would mean ready public access, greatly enhancing the land’s potential for “development.” Word was out that it might sell for $6-10 million. I don’t know who generated the idea of paving the road, but I suspect some booster was thinking about profits from tourism, increased tax revenues, or both.

None of this would have come about, however, had our government not stolen Pe’ Sla from the Sioux tribes in 1877 and converted it into private property. Yet even this hadn’t seemed to be an insurmountable barrier for the Sioux, because the legal owners both cared for the land and gave the tribes ready access to it. The coup de grace proved to be Pe’ Sla’s proximity to two popular tourist locations: Mount Rushmore and the 19th century gold camp of Deadwood, where Wild Bill Hickok was shot in the back of the head while playing cards.

The two business-as-usual strategies for killing this sacred site and then turning it into money emerged from the prospect of a paved road. One was the slaughterhouse approach: slice it into lots along the new road: motels, restaurants, condos, houses, maybe a golf course. The other approach was taxidermy: let the public pay for paving the road and then sell it as an upscale ranch, keeping its boundaries, i.e. its hide, intact. The heavy volume of traffic whizzing by on the paved road would easily dissipate the pristine energy that Pe’ Sla has always emanated, thus killing its spirit, but revenues for the campground and store nine miles down the line would shoot up.

As of early September, 2012, however, another approach to Pe’ Sla’s future has emerged. A Sioux tribe asked a federal agency to intervene in the matter and it also put up $1.3 million as an offer of earnest money in an effort to buy the sacred site from its legal owners. As a result of these overtures the auction originally scheduled for August 25 was cancelled. Nevertheless, whether the tribes can seal the deal by coming up with the rest of the money remains to be seen.

Note that this third approach involves draining funds from the tribes that they can ill afford in order to preserve a sacred site that was stolen from them in the first place. There is only one honorable solution here, which is for our government to give full ownership of Pe’ Sla back to the tribes, together with a declaration of profound apology for confiscating it, while also paying the legal owners a decent sum from the federal treasury as compensation. But that would require thinking outside the dominant paradigm, so it won’t happen.

In all of this it has made no difference how important Pe’ Sla has been in helping the Sioux bond with the land. Nor has it mattered how special, even unique, its energy is. It certainly hasn’t mattered what precious lessons this sacred site could teach the rest of us, even if those lessons could play a part in helping us survive. (See “Sioux Tribes Upset Over Sale of Sacred Site in S.D.,” Charleston Gazette, 8/19/12; “Pe’ Sla Purchase: Not Out of the Woods Yet,” Indian Country Today Media Network, 9/7/12).

What would we have done differently if we had never lost our love for the land? Would we have sawed down our forests like a boundless army of termites? Would we have stuffed our bruised ecosystems with seven billion humans? Would we have riddled the countryside with concrete and clogged it with motor vehicles? Would we have farted out enough CO2, methane, and nitrous oxide to bring on a global warming calamity?

I don’t think so.

Click here to read the PDF version of this article

Click here to continue reading the PDF version of this article

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Beautifully written, man. And I know how you feel, talking about such nonscientific things. You feel it, but can’t really explain it, and it’s hard to even talk about without sounding crazy. I don’t bother with most people.