“People will remember today as a day to date things in their lives from, in the same way they did with President Roosevelt. They say, where were you when President Roosevelt died…. they will say the same thing about where were you when you first heard the word of President Kennedy’s assassination.”

–Harry Reasoner, CBS News

5:42 p.m., November 22, 1963

“There is implicit in all human tragedy a waste, a pointlessness. Tragedy unobserved is even more pointless. But tragedy unremembered surely must rank with profound sin.”

–Saul Pett, 1964

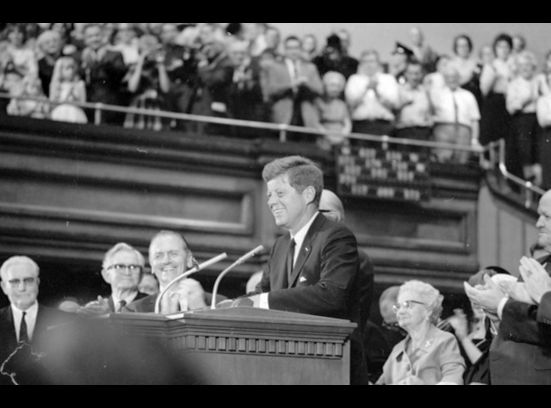

In the early autumn of 1963, John Kennedy made a trip to Utah. Still shaken by the previous October’s Cuban Missile Crisis, the President had something on his mind, and he wanted to tell the citizens of the most conservative state in the union what it was. Elected as a Cold War warrior, a president who “would pay any price, bear any burden” to fight Communist aggression around the world, Kennedy had traveled to the brink of global nuclear annhiliation and now his world view had changed.

And so, on October 3, 1963, in the Mormon Tabernacle on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, the president laid out his vision of the future, which included cooperation, not confrontation with the Soviet Uniion. It was a risky proposal to make anywhere; in the Rocky Mountain West, it almost seemed suicidal. He talked about the Limited Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union, just ratified by the Senate:

“It took Brigham Young 108 days to go from Winter Quarters, Nebraska, to the valley of the Great Salt Lake. It takes 30 minutes for a missile to go from one continent to another…That is why the test ban treaty is important as a first step, perhaps to be disappointed, perhaps to find ourselves ultimately set back, but at least in 1963 the United States committed itself, to one chance to end the radiation and the possibilities of burning.”

To his surprise, the audience erupted in cheers and applause. Even here in the heart of the conservative Rocky Mountain West, Americans were weary and scared of the Cold War and the constant threat of world annhiliation. Always the politician, Kennedy considered the enthusiastic response and wondered if his chances of electoral success in the western states had not improved. Clearly, he would be back in 1964.

Six weeks later and a thousand miles away, a gray drizzle fell on the crowd of five thousand Kennedy supporters who had gathered in the parking lot across from the Ft. Worth Hotel Texas. The president of the United States was expected to address the group in a few minutes, and the man they awaited gazed down from the vantage point of his eighth floor suite.

John Kennedy was joined by two of his closest aides — Ken O’Donnell and Larry O’Brien. O’Donnell, leafing through Friday morning’s Dallas News, had fallen upon an ugly black-bordered full page advertisement. Its sardonic heading read — “Welcome Mr. Kennedy to Dallas” and it was paid for by the local coordinator of the John Birch Society. The two men watched the President read each line and then saw him thrust the paper aside. Kennedy returned his gaze to the parking lot below and the milling crowd:

“You know,” he said, “they talk about security, and protecting the President. But look at this.” He stared at the unprotected platform where he would deliver his pre-breakfast address. “If anyone wants to get you, they can always do it.”

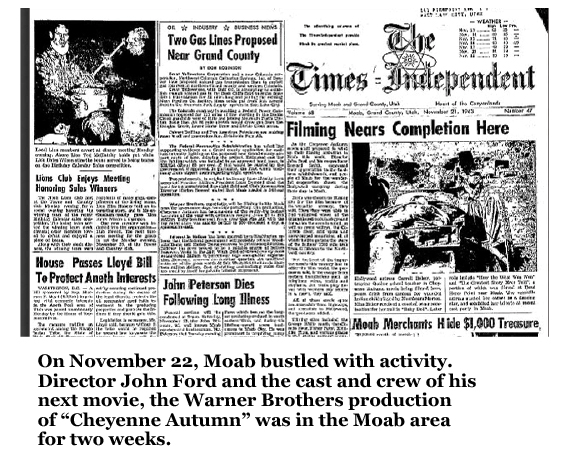

In Moab, Utah the dawn of November 22nd broke sunny and bright; though the temperature had fallen to just below freezing during the night, the desert sun quickly removed the chill from the air and by noon the thermometer read in the 50s—typical fall shirtsleeve weather in the canyon country.

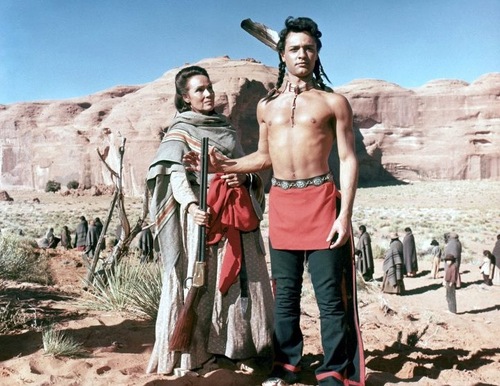

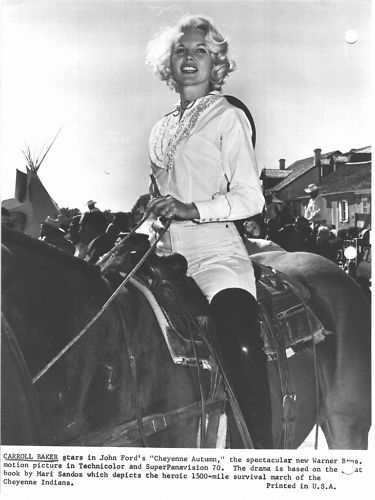

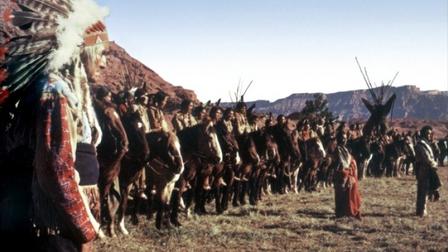

The town bustled with activity. Director John Ford and the cast and crew of his next movie, the Warner Brothers production of “Cheyenne Autumn” was in the Moab area for two weeks. The film starred Richard Widmark, Carroll Baker, Gilbert Roland, Dolores Del Rio and Ricardo Montalban and they were all here, along with a supporting cast and crew of about 350.

It wasn’t Director Ford’s first trip to Moab and he indicated it wouldn’t be the last. Not only was the scenery around Moab spectacular, Ford was grateful “to be able to escape such modern installations as telephone wires, traffic and airplanes…jet trails play havoc with western sky scenes in a movie.”

Every motel and guest house in town was filled with cast and crew and locals watched in awe as the celebrities frequented Moab’s eateries and night spots—Carroll Baker led a limbo line one night while Richard Widmark maintained the beat with a pair of chop sticks. But, as the Times-Independent reported, while “most all cafes are gathering spots for the stars, and although townspeople have enjoyed being present to see the famous stars, they have courteously respected their privacy.”

Despite the movie crew, places to rent in Moab were still available. Holiday Haven advertised lots that week for $30 a month, “all utilities furnished.” And if you wanted to buy a home in Moab, a three-bedroom house in downtown Moab was listing for $4,250.

On the morning of November 22nd, the film production was shooting at the movie-made Indian village near Tommy White’s ranch (now Red Cliffs Lodge) and Ford was not getting the performance that he wanted from one of his stars. It was the climactic scene of the movie—Ricardo Montalban and Sal Mineo fight to the death for a woman they both love and when the smoke clears, Mineo lies dead. Dolores Del Rio, portraying Mineo’s mother, falls to her knees and is supposed to weep uncontrollably for her fallen son. But for the camera, the tears would just not flow the way Ford expected them to. Take after take was shot, but Ford was dissatisfied with each one. He was determined to get it right, even if he had to stay there all day.

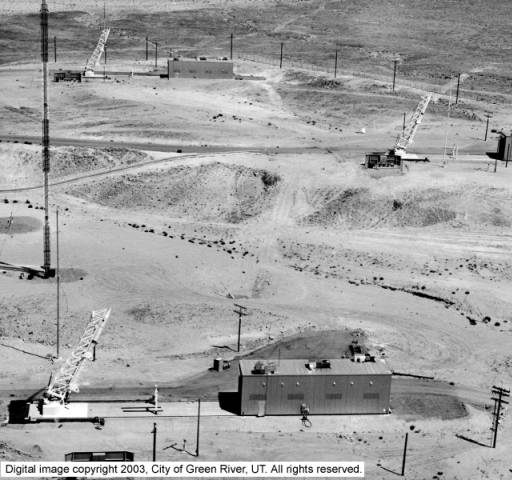

Fifty miles north, representatives of the U.S. Army and Air Force were putting the final touches on preparations for “Green River Day.” The armed forces were inviting the community to become “officially acquainted” with missile launch facilities east of town. The test launches of the Athena missile, to begin in 1964, were designed to study re-entry techniques. The notice reminded the public that refreshments would be served, and that the activities would begin at 1 p.m. on November 22.

In Dallas, Air Force One touched down at 10:38 a.m. (Mountain Time) at Love Field. President and Mrs. Kennedy emerged from the rear door of the Boeing 707, waved to the crowd and descended the stairs to the tarmac below. After being introduced to yet another group of local dignitaries, the President and his First Lady plunged into the crowd of greeters that waited just beyond a chain link fence. A reporter for radio station KLIF described the scene:

“This is a split-second operation for the Secret Service and Signal Corps. Nothing left to chance. Every possible precaution has been taken… The First Lady has been presented a lovely bouquet of red roses which contrasts nicely with the bright, pink suit she’s wearing….”

As the Kennedys moved along the fence, the reporter continued, “This is where the Secret Service has their point of tension. When the President stops moving, they say, this is their time of greatest concern.”

The custom-built Lincoln convertible, code-named SS-100X by the Secret Service, pulled beside the President. Reluctantly, he left the cheering throngs behind him and climbed into the back seat of the open limousine. In Dallas, it was 11:57 a.m.

In Blanding, Utah, where the clock showed it was still mid-morning in the desert southwest, John D. Nielson, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Morgan N. Nielson, looked anxiously to the future. Only a week earlier, he learned that he had been selected as a Peace Corps Volunteer. His assignment would take him half way around the world to Tanganyika where he would teach English grammar. The Peace Corps, a program close to President Kennedy’s heart, called out to young people around the country. Nielson was grateful to be one of the chosen.

For Dwayne and Georgie Christensen, November 22nd was already a day to grieve. At 3:04 that morning, Mrs. Christensen had given birth to a baby girl, Shelley Gay Christensen, but she died just three hours later. Services would be held on Sunday.

In Grand County, the weekend rapidly approached and Moabites planned their Friday evening. At the Downtown Holiday Theatre, the marquee featured two Jerry Lewis comedies — “Don’t Give Up The Ship” and “Rock-A-Bye Baby.” But mild autumn weather had kept the Grand Vu Drive-in open and gave movie goers an option. Playing on November 22-23-24, “Tammy and the Doctor.”

At White’s Ranch, Dolores Del Rio was still struggling to properly cry for John Ford’s camera….

SS-100X turned left from Houston to Elm Street. The crowds that were so dense on Main had thinned, and the big car entered a grassy area called Dealey Plaza. To the right, a squat six story brick building called the Texas School Book Depository loomed over the park-like plaza. Ahead, Elm St. passed beneath a broad railroad viaduct known locally as the triple underpass. Beyond it, a young reporter for CBS News named Dan Rather waited for the motorcade to pass by. Suddenly he realized, something was wrong. Rather remembered:

“Wait a minute, I thought. The motorcade has taken a wrong turn here. It seemed to be moving very fast. Something seemed wrong. I’d heard no shots, but I ran to the crest of the railroad tracks, and the scene I saw, I’ll never forget. There were people screaming, there was great confusion. I knew something was very wrong.”

Four minutes later, UPI Correspondent Merriman Smith seized a radiophone in a car 150 feet behind the President’s, and began dictating to the Dallas Bureau: “Three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade in downtown Dallas.”

By 1 p.m. (noon in Moab), seventy-six million Americans were aware of the assassination attempt. Among them, stunned residents of Moab gathered in groups in their homes and in downtown stores and waited for news of the young President’s condition. News reached the set of “Cheyenne Autumn,” by way of a local man who had been hired as a movie extra. A transistor radio broadcast the details, as this real-life drama unfolded to an audience who specialized in make-believe.

Members of the cast and crew dissolved into tears but John Ford was not yet ready to release them. Director Ford forced Dolores Del Rio to recite her lines one last time. This time the tears flowed freely.

“Cut. Print.” said Ford grimly. Her performance was perfect, but it didn’t require acting.

At 12:36 p.m. Mountain Time, the face of Walter Cronkite flickered on black & white TV screens in the Moab Valley. In shirtsleeves, Cronkite, like the nation, could only wait. Behind him, young errand boys leaned over UPI and AP ticker tape machines waiting for the FLASH that no one wanted to hear.

Cronkite, describing the anti-Kennedy sentiment in Dallas, described U N Ambassador Adlai Stevenson’s recent visit to Texas:

“There were some fears and concerns in Dallas that there might be demonstrations that could embarrass the President…”

In the background, a young man tore off a sheet of paper from the UPI ticker and raced off camera. Cronkite continued, “It was only on October 24th that Adlai Stevenson was assaulted, leaving a dinner meeting there…” Cronkite was handed the flash. He looked down at the piece of paper, put on his glasses, took them off…

“From Dallas Texas, the flash, apparently official, President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago.”

Cronkite’s mouth tightened. His jaw clenched and trembled violently. For five long seconds, he could not speak.

“Vice President Lyndon Johnson has left the hospital, presumably to take the oath of office and become the 36th President of the United States.”

John Ford dismissed the cast and crew members for the remainder of the day. School children were allowed to go home early. Adults sat stunned and disbelieving in front of their TV sets. That evening, Father John Rasbach performed a High Requiem Mass at the Moab Roman Catholic Church. On Saturday morning most of the film company flew out of Moab on Frontier Airlines, headed back to Los Angeles. Only 48 hours earlier, one of the stars had complained, “Leave this beautiful weather and Moab and Indian Summer for fog and smog?” Now they left in silence.

For the next three days, Moab looked like every other town and city in America, bound together by a common loss and a sorrow too deep for tears.

Dolores Del Rio’s grief is recorded forever on film.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here. andhere.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

thanks .. an interesting time