The Sinai Peninsula is one of the most spectacular places on the face of the earth. Armies of the ages have used the rolling sand dunes of northern Sinai as a highway to battle. Ancient Pharaohs, Mesopotamian monarchs, Alexander the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte knew the ancient road of northern Sinai.

Southern Sinai is a different story. As you go south, the rolling sand dunes turn into hills, which turn into ridges, which transform into some of the most rugged mountains on the face of the earth. The spectacular landscape of southern Sinai is almost beyond comprehension.

I made a handful of trips to the Sinai in the 1980s, first as a student and then as an employee of the Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center.

A visit to the Sinai in the 1980s was nothing short of an adventure. Our small groups would cross the border at Taba into the no-mans land of the Sinai. At the time, the Sinai was administered by the United Nations and was classified as a demilitarized zone. What a strange title for a place full of the refuse of war. The burned-out shells of destroyed tanks, carefully marked mine fields, and debris of death and destruction were at every turn, all the legacy of epic battles between the Israelis and the Egyptians in 1948, 1967 and 1973.

One group of students saw the barrel of a rifle sticking out of the sand. They were horrified when they pulled the barrel out of the sand and discovered two dismembered arms still attached to the stock of the rifle.

The Sinai is remote and rugged, isolated and raw. A trip to the Sinai required a group to bring everything with them: water, food, first aid, gasoline, everything. Our groups would spend two days with the barest of rations and sleep under the stars. Tourist accommodations were limited, medical services were nonexistent, and the familiar comforts of life seemed distant and far away.

While there are a few isolated communities along the Red Sea coast, signs of civilization disappear as soon as the road turns inland. The only sign of human life would be an occasional Bedouin with a small herd of camels. The silent Bedouin live a nomadic life in the desert, as they have for generations. They rarely interacted with visitors.

Nebi Musa is one of the tallest mountains in the heart of the Sinai. The name means The Prophet Moses in Arabic. At the base of sits St. Catherine’s Monastery. The monastery was built 1700 years ago and has never been destroyed. Manned by a handful of Greek Orthodox monks, life has changed very little over the centuries at St. Catherine’s. The monks seem an anomaly in the stark desert. They dress in heavy black robes and speak very little.

I visited St. Catherine’s several times over a two-year period and became acquainted, by sight, with one of the monks. One day, he motioned to me that a mass was going to be held in the ancient chapel and invited me to attend. I accepted, and awkwardly tried to thank him afterwards. I was surprised when he answered in clear English, with a distinct American accent. I asked him where he learned his American English and he answered that he grew up in Salt Lake City before dedicating himself to his life of service at St. Catherine’s.

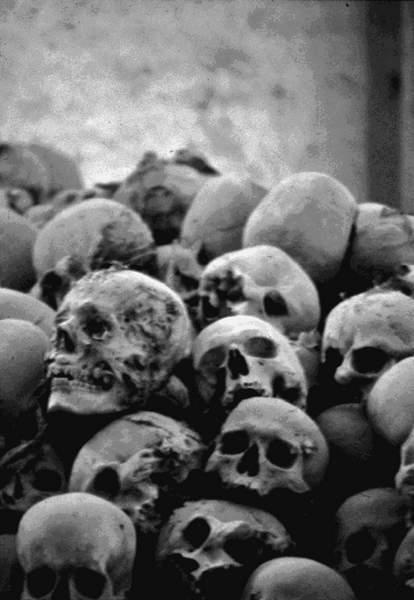

These monks live a life of solitude in the desert and when their life ends, they are buried in one of a  handful of graves at the base of the mountain.

handful of graves at the base of the mountain.

The graves are few in number because there is very little soil in the Sinai. Solid rock mountains leave very little space, or soil, for a grave. So after several years, the bones of the monk will be dug up and taken to the Charnel House, where they are sorted… skulls in one room, arms in another, etc. This makes the grave available for temporary occupation by the next deceased monk.

Despite the dry landscape, the monks have developed their limited water resources. Any rain that falls simply runs off of the solid rock and flows to the valley floor, where it is collected in cisterns. In this way, every miniscule drop of rain can be captured and a simple and austere life can be sustained in this most barren area.

St. Catherine’s is the home of one of the most remarkable libraries on the face of the earth. The monastery has largely been forgotten by the passage of time. The dry climate is perfect for the preservation of documents and the monastery is full of documents. In fact, a treaty letter in the monastery, signed by Mohammed himself, has offered protection to the site for nearly 13 centuries.

Time – and armies – has marched by and the centuries have clicked away in this remote and forgotten corner of the earth.

Despite being one of the most isolated places on earth and seemingly far from any vestige of civilization, it was from Sinai that the core of our civilization developed. Moses and the Children of Israel escape from Egypt and found stark refuge at Sinai. Moses went to the “mountain of God” and brought down stone tablets.

You have to go to a museum or university in order to study ancient Egyptian life, religion and culture. The same is true of the life, religion and culture of other ancient societies; they are strange and distant and unfamiliar. However, there is one exception. The monotheism that sprung from the mountains of Sinai is vibrant and alive today. Modern Judaism, Christianity and Islam, which represent the belief systems of nearly half of the earth today, share a common genesis at Sinai.

I do not think that it is a coincidence that these developments, which impact our daily society millennia removed from Sinai, emerged from such a stark and rugged and unforgiving landscape.

In the 1980s, our groups would travel all day through the rugged desert in order to arrive at the base of Nebi Musa in the evening. After a few hours of fitful sleep, we would start our hike soon after midnight. The trail climbs nearly 2,000 feet from St. Catherine’s to the top of the mountain.

Even though we had flashlights if needed, we would soon learn that it was better to let our eyes adjust to the night and simply hike in the dark. The most spectacular night sky imaginable would provide enough light to hike. Many visitors had never experienced such a remarkable night sky.

It was a walk in total solitude, interrupted only if you chose to talk with a friend. The trail is wide and relatively flat at the beginning, but gets steeper and steeper as you climb. The final stretch consists of nearly 1,000 stone steps to the top of the mountain.

The absolute darkness, except for the night sky, meant that the mountains were encased in the dark of the night and only slowly began to reveal themselves as the dark began to lift toward dawn. After several hours of struggling in the dark, our groups would arrive at the top in time to experience a breathtaking sunrise.

Quite often, our small group of less than 100 was the only group at the top.

It is a remarkable setting, to say the least. I would venture to say that several of the most meaningful events of my life took place in the 1980s on this far away mountain in the middle of the Sinai Peninsula.

Fast forward to 2006, when I had the opportunity to take a group of friends and relatives to the Middle East. One of the highlights of our tour was a trip to Sinai. Even though the last active war in the Sinai took place more than 30 years ago, the residual effects of our current wars was not far away. On the way to St. Catherine’s, we passed through the Red Sea resort community of Dahab just two weeks after a terrorist attack had claimed the lives of 30 people.

The group arrived at our hotel accommodations and I was amazed to see western-style buildings with the largest outdoor swimming pool I have ever seen. We went to our rooms to find cable TV, where I had the choice of watching Greta Van Susteren discuss the latest findings in the Natalee Holloway case, a juggling competition in Las Vegas, or Mr. Magoo starring Leslie Nielsen.

In recent years, the Egyptian government has spent some of the billions of dollars in U.S. aid to bring “civilization” to the Bedouin. Instead of a nomadic life in the desert, the Bedouin are painfully adapting to life in establish communities. One of the largest of these communities is at the base of Nebi Musa.

After our early wake up call, we boarded the bus and drove down roads illuminated by streetlights to St. Catherine’s National Park. We began our hike, but it wasn’t too long before we arrived at the camel loading station and met Oscar, our Bedouin camel wrangler. Oscar (a name he picked up because his Arabic name is unfamiliar) was easy to spot: the fashionable tip of his fedora made him look like a member of the Rat Pack.

Oscar did all the talking and helped several members of the group secure a camel ride. They rode the camels up to the mountain to the bottom of the stone steps.

I decided to walk with my son. Bedouins, who were trying to change our minds about the camel ride, destroyed the solitude of the walk. Every few feet, a mysterious figure would appear out of the dark and whisper an offer to get us a camel ride.

The trail had also changed. Instead of nothing but a simple trail, there were rock “rest huts” and “coffee shops” every few hundred yards. They were lit with kerosene lamps and offered a full range of snack foods and soft drinks. I wouldn’t have been surprised to hear the whir of an espresso machine.

Once the trail reached the stairs, the hassle began in full. Bedouin were begging for the chance to escort hikers up the stairs (for a fee) or to have a blanket (for a fee) or even to have a mattress at the top (of course, for a fee). They would grab you by the elbow and push you along for a few steps before demanding payment.

It was a disappointing situation, to say the least.

Light pollution has also been introduced to the Sinai. Instead of mountains shrouded in the dark of night, the miles of roads with streetlights create an eerie glow. Once we arrived on top of Nebi Musa, the runway lights of the new Sinai airport twinkled in the distance.

We arrived at the top with an estimated 1,000 other visitors. The group inundated the top of the mountain. And remember, this was just two weeks removed from a terrorist attack in the nearest community. I wonder how many thousands would climb the mountain under more peaceful circumstances.

The sunrise was beautiful, the setting was spectacular, the climb (or ride) was memorable, and the experience was wonderful. I can’t help but wonder, however, if the new developments at Sinai have destroyed the very thing that gave the area so much charm.

Solitude is replaced by beggars. Noble, silent and mysterious Bedouin have become Oscar in a fedora. The night sky is blotted out by airport runways, street lights and rock huts selling Orange Fanta. Hotels, swimming pools, and crowds. The magic of Sinai is becoming overwhelmed by the efficient and annoying hum of civilization.

I wonder if my Greek Orthodox friend at the monastery has given up and returned to Salt Lake City.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!