“Although it is generally said that mountains belong to the countryside, they belong to those who love them.” – Zen Master Dogen, 13th century

Seventy miles north of San Francisco Bay. Even on a bright day, from several miles inland along the Russian River, I could see the white layer of fog running up the westernmost slope of the coast range. Capricious Pacific Ocean fogs swathe these low ridges with moisture, moisture that would otherwise be carried far inland by weather systems.

The old resort town of Guerneville lies along the river in the heart of the coast range. The climate here is cool and wet: along with the ground fog, over 50 inches of annual rainfall patters the area, with some winter mornings dipping below freezing. Just enough freezing it seems to take palm trees out of the mix, leaving an ideal habitat for gigantic conifers to evolve and thrive. And so they have.

That is why after refreshing ourselves with state of the art cups of joe at the Coffee Bazaar in Guerneville Gail and I drove northward a few miles to the Armstrong Redwoods State Reserve Area and walked on a trail through the Redwoods.

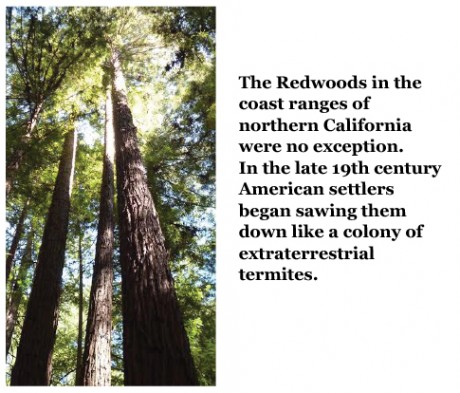

They are the tallest trees in the world and some have been known to live over 2,000 years. It takes 400-500 years for them to reach maturity but when they do their small-spiked needles rise above all others, absorbing pure sunlight.

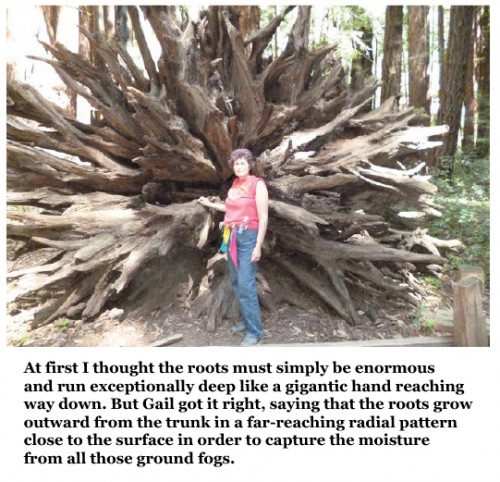

We marveled at the following: what having a tree trunk that wide and that delicately striated yet massively heavy and that tall must require of a root system that also serves as a network of sentient pipes unsurpassed at sucking up groundwater. At first I thought the roots must simply be enormous and run exceptionally deep like a gigantic hand reaching way down. But Gail got it right, saying that the roots grow outward from the trunk in a far-reaching radial pattern close to the surface in order to capture the moisture from all those ground fogs.

Well, so much for naturalistic observations. When I began looking straight up the mammoth trunks of those mothers my brain lost any sense of scale. An example: there was a Redwood with a wooden sign beneath it in full-size yellow letters that had just advised me that the tree was 310 feet high, 13.8 feet in diameter, and 1,300 years old. Yet when I gazed straight up at it all those numbers melted in my brain. I only knew that this tree was an ancient and honorable being and that this was a sacred place.

Of course, asserting that a natural setting is sacred doesn’t sit easy with everyone in our big-dawg, reductionist culture. One reason is that such a statement, whether the speaker is aware of it consciously or not, necessarily raises the issue of whether our omnivorous settler ancestors have chewed the place to pieces in the past. And whether some of our fellow citizens are, unfortunately, eager to do the same today.

Except for Thoreau, Emerson, Whitman, and a very few others there was virtually no environmental consciousness among Americans of European descent until the tail end of the 19th century at the earliest. Only the Native Americans felt a sacred bond with their ancestral lands, and until the days of Teddy Roosevelt the dominant American society did virtually nothing to protect wild areas, no matter how appalling the destruction it inflicted upon them.

The Redwoods in the coast ranges of northern California were no exception. In the late 19th century American settlers began sawing them down like a colony of extraterrestrial termites. Fortunately, Californians with an emerging environmental consciousness got sufficiently pissed off and in 1901 the state government began protecting the Redwoods. But meditate on the mayhem: roughly 85% of the Redwood trees were hacked to pieces; only 10% of the original trees were given protection in state and national parks. Five percent have somehow survived unprotected.

Thus we saw a lot of wide, moss-covered Redwood stumps as we walked along the trail. Later as we hiked up and down roads in the area we saw many surviving unprotected trees: which only showed me how enormous the original population of Redwood trees must have been. It was a cheerless thing to realize all this, yet I hope it’s a kind of grief that more and more of us are sharing. As Native Americans comprehend better than any of us, you don’t tear your lands apart when you love them with an undivided heart. In the end that’s what it will take to keep any of these places and the ecosystems that comprise them safe.

But here is the thing. When a mature Redwood dies young trees grow up in a ring around it: a “fairy ring.” Around these old sawed-down stumps we passed one lovely fairy ring after another.

***

“I strongly believe that consciousness cannot be localized in any particular place – not even in the brain.” – Pim van Lommel, M.D.

While I believe saying that ecosystems and landscapes are “sacred” is important in protecting them, I also think the word is misleading, or perhaps incomplete. Because when we say some entity or place is sacred it nevertheless remains outside of us. It is still other; it is “not-me.”

Consider the following, however, from Lisa Grayshield, Ph.D., who is a member of the Washo tribe in western Nevada: “It is common among my people to hear someone say they are the land and the land is them…While human interactions are important, they are not held above the interactions that take place in the natural environment.” (See note below on her article.)

I don’t believe she was reciting a mere religious teaching or some philosophical tenet from Washo culture. Quite the opposite: I surmise that for thousands of years people in Native American and other indigenous societies have ventured far into the wildness of the land for extended vision quests and that as a result a significant number of them have had experiences in which the entrenched separation of self and other disappears: that they experience, just as Dr. Grayshield said, that they are the land and that the land is them. Not only do I suppose that such experiences happen, I suspect that they have been common for multi-thousands of years and have perennially worked their way into indigenous cultures, informing the people how to regard the natural world around them: as themselves.

That a human can have such an experience is unfortunately not well known within Western culture, much to our loss in my view. It is, however, well known within traditional Asian societies. For example, note the following from Japanese Zen Master Dogen: “I came to realize that mind is no other than mountains and rivers and the great wide earth, the sun and the moon and stars.”

It turns out that Edward Abbey himself likely had such an experience, which he shared in his later years with his old buddy Jack Loeffler:

“‘…But there was a time back in Death Valley where I had what I guess was as close to a mystical experience as I’ve ever had. That was years ago. I was a young man. I’ve never had anything quite like it since. As close as I’ve come is after I’ve been out camping somewhere for at least two weeks. It takes at least that long for me to really get into it and leave all the baggage behind.’

“‘Can you describe what happened back then?’ I asked.

“‘Well, it’s not something that’s easy to remember intellectually. It was more the way I felt. As I recall, I felt like I wasn’t separated from anything else. I was by myself at the time. It was as if I could perceive some fundamental activity taking place all around me. Everything was alive. Even the rocks. I was part of it. Not separate from it at all. I wept for joy or something akin to joy that I can’t really describe. It was a long time ago. It’s not something that can be remembered in the normal way. Or at least normal for me. The only time I can get close to it is out camping. I don’t get to do that enough. Not nearly enough.’

…

“‘…In a way, that was one of the most important experiences of my life so far. I’ve tried to get back to it, but I don’t know how…’” (Jack Loeffler, Adventures With Ed, 2002, pp. 242-243.)

Now look at the following landscape description from Abbey’s novel Fire on the Mountain, which he wrote in his early to mid thirties and which was published in 1962. He set the story in the Tularosa Valley of New Mexico in the Chihuahuan Desert and tells it from the vantage point of twelve year old Billy Vogelin, who is visiting his grandfather for the summer.

“‘Look,’ Grandfather said proudly, ‘see how the light comes down the mountain now. Rolling toward us like a wave.’

“Old man, proud of his mountain. I looked where he pointed. Swiftly and smoothly the sunlight was spreading downward from the peak to the crest of the lesser mountains north and south, down over the belt of pine to the juniper and pinyon stands of the foothills. Bands of light extended across the green sky, passing above us from the east, expanding from the fiery core that swelled below the rim of the world. Turning in the saddle I looked for the sun and in a moment the first arc of it appeared, then more until the entire fireball rose, dazzling and incredible, more beautiful than thought, above the Guadalupe range eighty miles away.” (p. 33.)

Those of us who have had the pleasure of reading Abbey’s books have been repeatedly struck by the majesty of his landscape descriptions. They are tender, lovely, and unforgettable. With the possible exception of Ann Zwinger, I can’t say he has an equal.

I do acknowledge that it would be simplistic to try to explain the splendor of these descriptions as the result of his experience of non-separation in Death Valley as a young man. I believe it’s much more likely that what he wrote sprang from his life as a whole. Nevertheless, the way he wrote about the land is congruent with that single experience; they dovetail completely. Whatever his eccentricities and foibles may have been, Abbey still has much to teach us about what unconditional love of the land is.

I say this with a touch of sadness because I have learned from long experience that on a conscious level people can believe they love the wildness of the land and even at times seek solitude in it but that within themselves they can remain divided, all too often by the lure of sizable paychecks or financial investments.

We need a new kind of consciousness in which that love is undivided and that paradoxically harks back to some of humanity’s oldest traditions.

Notes: (1) Dr. Grayshield’s quotation is from her article, “Indigenous Ways of Knowing as a Philosophical Base for the Promotion of Peace and Justice in Counseling Education and Psychology,” Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, Volume 2, Number 2, Fall 2010, p. 12. (2) I have previously utilized two of these quotes, Dr. Grayshield’s and Edward Abbey’s account of his experience in Death Valley, in the Zephyr. But they’re so good I returned to them.

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to the Zephyr.

He lives in Beckley, WV.

All photos courtesy of Scott Thompson.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!