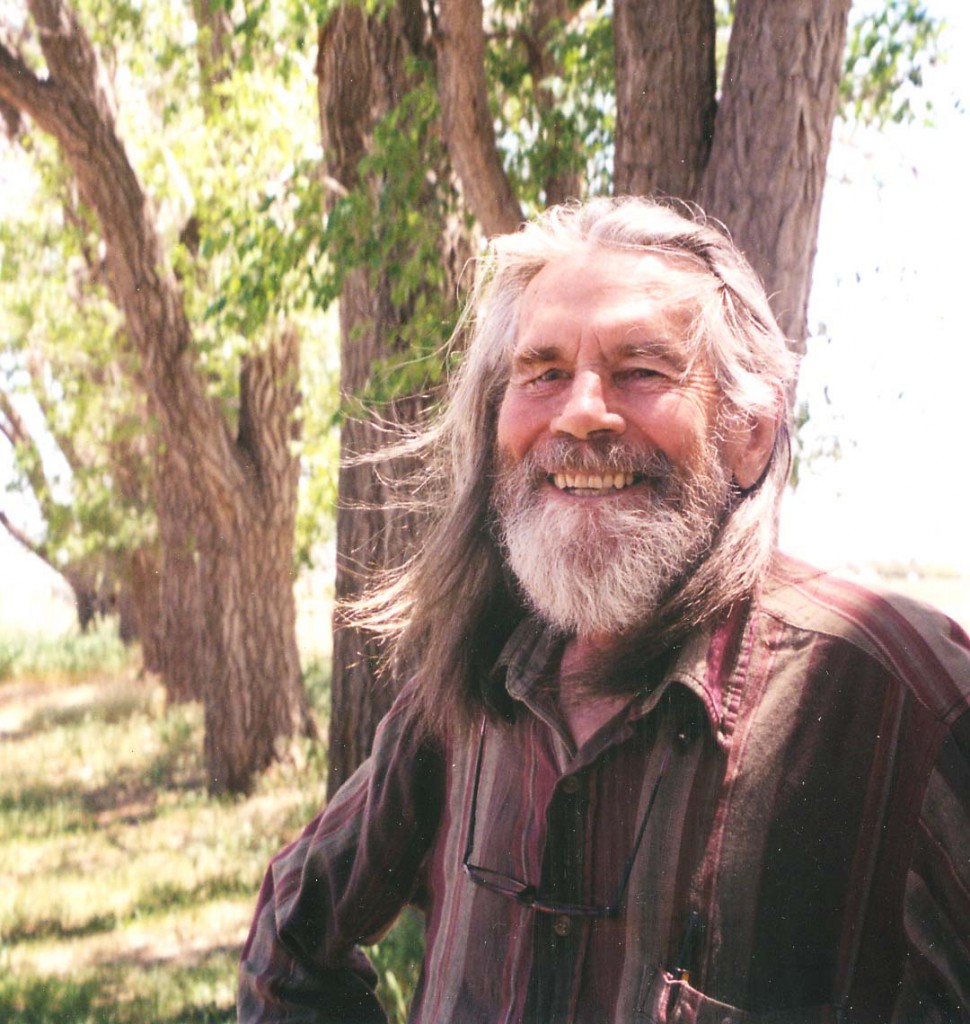

Martin Murie passed away last night. He was 86 years old. Martin was my dear friend for a quarter century and a loving mentor. He was still standing on corners protesting War and advocating PEACE to the very end. A gentleman in every way…a gentle man….JS

Here is one of my favorite Martin’s Murie stories…

Using the body, all of it, moving, exerting. Not much of that was visible along the highways of this big continent as I urged my faithful 4-cylinder pickup from the north rim of New York state to Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and back. Highways are where you get a dramatic look at the passive nature of our automaniacal lives, people of all ages touching their digits to the faces of machines to make the machines spit out cokes, pepsis, candy, ice, fuel. We press a lever to get coffee. We slip plastic into slots to pay for things or to open heavy metal doors of Super 8s and the other massive structures of that tribe. We put quarters into slots for the daily dose of “news” print or to make a machine give up a small box of detergent to feed a laundromat top-loader.Rotary phones, remember those? You don’t punch or push, you get to actually move a piece of the machine, several times, to “dial up” the number you want. If it doesn’t deliver you dial Operator.

Quite often machines won’t behave. They go on strike, they sulk. At a mini-mart an enraged voice made me turn from feeding gas into the pickup. An old guy about my age was asking the world, “What the hell am I supposed to do?” I was pleased. For once I was in a position to deliver digitary advice instead of searching for it.

“You have to press “Pay Inside,” I told the old-timer, and then we were two old-timers telling each other how the old days made more sense. At another stop for gas and coffee I was buffaloed by the gas dispenser that refused to deliver. I gave up, went inside to complain, but the woman behind the counter gave me a big happy smile.

“Let’s go take a look,” she said as she skipped around the corner of the counter and out the door so fast I had to hustle to keep up. I think her vim and joy came from the chance to get away from the touch-and-slide routine, to move, to move fast, to go! At the dispenser she went through the routine I was pretty sure I’d just gone through three times and … the damn machine started pumping gas.

“I did all that,” I said, a bit disgruntled. “Nothing happened.”

She laughed and skipped away, then stopped, turned, said, “You loosened it.”

Driving across Nebraska and Wyoming against a headwind, I had lots of time to spin fantasies about the land and the drought and the bad news that my whonky antenna picked up from time to time. Out of that mish-mash of wind and static and random thoughts came, repeatedly, the simple idea that we are, all of us, crazy. We’re forced to adapt to the dumb acts and ideas our “civilization” shoves our way, we have to go a bit haywire, to survive. I mean, how else could we possibly keep going, day after day, while putting up with lies from our leaders, deaths from the wars, Nature making unfriendly returns and millions of us doing nothing about it except hanging out little flags and yellow ribbons and punching machines and hoping they’ll do the right thing, or tapping a code into a cell phone for a chance to talk to another human. Isn’t crazy the word for this?

But my haywire urge right now is to sing the joys of putting ourselves, our bodies into action, doing things. Not on a Nautilus. Not in super athleticism. There’s a difference here: by doing something, I mean making a difference in the outer world. Oh sure, making a difference in our bodies is good, we all ought to exercise and eat right and so on … this is vitally important … but I’m on another track here, looking for changes, out there in the world, changes wrought by human effort.

A little east of Chadron, Nebraska I stopped to renew acquaintance with the Museum of the Fur Trade. It’s on the site of the American Fur Company’s Bordeaux Trading Post, established in 1837. Five dollars entrance fee. On U.S. 20, northwest Nebraska. I went into the back yard of the museum to take a few photos of two sod-roof log structures built into a south-facing slope. I had admired the tenacity of those logs on previous visits and this time the sun was shining brightly at just the right angle, highlighting the dry and thoroughly weathered dove tail notches that had been shaped one hundred and sixty seven years ago.

I was remembering my own dove tail project. It had taken three summers to build our cabin that did double duty as a support for the south end of the ancient woodshed. The first summer was devoted to felling, limbing and barking larch, spruce and fir, then dragging them out of the swamp to a seasoning site. In the next two summers I put the logs together, learning as I went.

There was a lot to learn, from the way to hone a good edge on a double-bitted axe to ways of measuring, hewing, levering. I’m in the cabin now, digits on keyboard, looking back to the mistakes I made. Some of the notches are not at all perfect, but some are pretty good and what a pleasure it was, to drop one notched log onto another and see and hear the clunk of true fit. The foundation isn’t perfect either, there has been a little frost-heaving, but now, after a number of winters the cabin seems to have found a solid footing of its own.

U.S. 20 is a good “Blue Highway.” If you’re crossing Nebraska this summer, try it. In Merriman, you might want to drop in at the Sand Café. Weak coffee, good pie. And Karen’s Kitchen in O’Neill is a modest place on the main drag, but has won an international reputation. Conversation, so-so coffee, excellent chocolate cake.

Near Chadron is Fort Robinson, a key cavalry outpost in the nineteenth century. Crazy Horse was killed there. That double-bitted axe! Bought the blade at a farm auction, hung it, sharpened it. The steel took a good edge, not too soft, not too hard. I was bragging about it to my neighbor, an experienced logger.

He said, “You must have got hold of a Black Raven.”

That’s what it was, Black Raven. It comes from the age of wood and steel. We are now in the age of plastic and glop. Is this significant? Sure it is. The consumer nowadays, that’s you and me, is a harried person holding down one or more jobs, striving to keep a household going. We don’t have time to learn hands-on skills. We pour chemicals, put things together with tape, cover errors with stuff out of a tube. Lots of iron still around, but at the “consumer” level it’s apt to be cheap stuff twisted into shape rather than forged or cast, prone to breakage or just too crappy to be of much use.

One summer, returning from walkabout in the west, I found Alison in our (1840s) house, working on a major project.. She had torn out old cracked plaster and split-board lathwork and installed insulation between studs and ceiling joists and was beginning to put up drywall. She had built a pair of wooden supports to hold the heavy 4-by-8 boards against the ceiling while we nailed them. This house was not put together with modern 4-by-8 units in mind; creative cutting of drywall was required. Alison is a master at imagining, measuring and then executing that kind of work. I’m more a rough carpenter type. But together, we got the job done. Hand-and-body work; a misery and a pleasure. I call it adventure.

Have you seen the TV ad for a claw on the end of a metal stick that will disturb garden soil, provided that soil is already tilled and sod-free? You don’t have to kneel on the ground, you don’t touch the ground, you have that stick between yourself and the good earth. Maybe the thing works better than I suspect. If you have one, let me know. At any rate, I’m taking the opportunity to hoist this gadget as a powerful symbol: loss of contact. Same with motorized tools. Witness the harried householder in a rush, pushing or riding the howling lawnmower. There was a time when kids had the job of pushing rotary mowers that went clackety clack. The kid had to push hard if the grass was more than a few inches high. Those were big jobs, they took time. The mower wouldn’t move if the kid didn’t heave his entire body into the action.

Ed Abbey had something to say abut this: “Pushing a lawnmower? Pushing? Nobody, nowhere, nobody in all of America, Japan or western Europe pushes a lawn-mower. They ride them, pushing levers, buttons, horns. Or their gardeners do. Their children, maybe, sometimes.” Quoted in Anderson Valley Advertiser, June 9, 2004. Time and motion were allotted differently in “the old days,” a fact we could have expanded on, we two old ducks at the digitized gas pump.

Materials were different too. Expectations, habits, a whole basket of differences. But when a couple of ancients get to talking about the ways things used to be you might notice that they’re not always revisiting an age when everything was hunky dory. I’ve listened to stories about farm kids learning the innards of tractors, trucks, everything mechanical, in order to dodge the awesome agony of hard physical labor in the fields.

I was lectured once by an oldster whose life had gotten much better in modern times: no more sleeping two kids to a bed, in a cold house, not enough food, not enough clothing, not enough money and too much grinding physical labor. Stories from the past, we need those, to help us figure out who we are. I’m speaking here against the awesome presentness of the present, that vacuum, that absence, that amazing non-remembrance of things past.

The young woman who happily dashed out of the Mini-Mart to wrassle the gas tank; I see now that the past was with her, whether she knew it or not; she and the rest of us come bouncing and squalling out of the tens of thousands of years of the evolving of humankind, the fine-tuning of muscle, sense and mind. Our bodies do remember; our bodies rebel against the couch potato life and the slow hours standing behind counters passively following routines, handing out burgers and taking in and handing out money and plastic cards. Back-breaking overwork, bodies rebel against that too. Ask any farm worker. Does this, now, in the formidable present, make us more uppity?

I hope so. When you put a coin in a slot and signal Diet Coke or Pepsi or Mountain Dew, look carefully at the metal and glass that houses the machines. Oh yes, they’re in there. Listen to them humming to themselves. Think about the grand total of such machines, stationed across the continent and overseas, throbbing, extracting from the earth. Do you ever wonder how long such contrivances will endure. I say, “These too will pass.”

Turning south from I-80, I got rid of the headwind, drove through Baggs,Wyoming and into Colorado. Along the way, somewhere north of Rifle in pitch black night a big buck mule deer. He stood stock still in the headlights, beautiful, for a half second, making a decision. I was doing that too, steering, braking. He bounded off, I drove on. At the next gas stop the machine told me my credit card was invalid. (Machine error, it turned out, later). I counted the cash in my billfold. Decision time. I remember the deer. He and I adapt to high-speed roads where metal creatures come at you with sudden blinding lights, as best we can.

We are fellow mammals on a planet getting stranger all the time. We have to pay attention to what’s new, and make decisions. If we don’t, we die. Life is that way. Yes, but what happened to put us in the now … those old stories, memories … those are with us too, part of the now, important.

One Response

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.

Dear Jim,

We are so saddened to learn of Martin’s death. Your characterization of him as a gentleman and a gentle man is so appropriate. Our sincere condolences to you for the loss of your friend and mentor; to his family; and to all of humanity — from the endangered animals to the victims of war — on whose behalf he dedicated his life. We were so inspired by his undying passion and we will do our part to ensure that his legacy lives on.

Sincerely,

Jan Baughman

Gilles d’Aymery

Swans Commentary