Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose.

Kris Kristofferson

I grew up during the cold war. It was a simpler war then… “us”, the good guys and “them” the bad guys. The Roman Catholic nuns told me about our “godless communist enemy” and taught me to hide under my desk to save me from The Bomb. As I grew older I saw that nothing was as simple as it first appears. I began to wonder about the Russians. Who were these people? Why did they want to bomb me? What did they look like? So, in 2004 I made my first trip to Russia. I flew to Moscow, and boarded a train to the city of Perm.

Perm proved to be a good example of a cold war city. Soviet missiles and cannons were produced there. It was a closed city during Soviet times… nobody got in or out. The city didn’t show up on any Soviet maps, to hide it from the US. I was told, proudly, that Perm was target # 13, thirteenth in line to be destroyed by US nuclear missiles. They were proud to be on the list, but wanted to be in the top ten!

Jump ahead to 2009. In Russia, the global economic meltdown that seemed to begin so suddenly, is simply called “The Crisis,” and they blame the United States, specificallyGeorge W. Bush for starting it.

After a period of relative calm between the US and Russia, “The Crisis” has served to revive another anti-American view in Russia. However, with the election of Barak Obama as president, there is at least a wait and see attitude from the

people I met. In terms of economy, the Russians had just gotten back on their feet after the fall of the Soviet Union. The collapse of the USSR had left them broke and confused about their national identity. Ronald Reagan woke up from his nap long enough to demand that the Berlin Wall come down. (“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”) For his part, Gorbachev had grossly underestimated the nationalistic pride still felt by the countries held to the USSR by force. It’s hard to hold an empire together by military might and once Moscow could no longer afford to rule by the Kalisnikov rifle, the countries surrounding Russia went their separate ways.

In 2004, the economy of Perm was booming. Eight hundred miles east of Moscow, at the foot of the Ural Mountains, Perm was close to the incredible wealth of natural resources that Russia could sell to the world for the rubles they desperately needed. Oil, mining, timber… all could move through Perm on the Kama river. But, Russia has always had a hard time exploiting this incredible cache of resources.

Here’s a country, eleven time zones from east to west, with little transportation into the vast area east of the Urals. The resources always seem to be just out of reach, unable to be distributed to the rest of the world. Some folks might be happy that the natural beauty would remain intact, but perhaps, not the Russians, so eager to improve their quality of

life.

So, the Russian economy came to be powered by oil. Where Lenin and Stalin used grain to enrich Russia, the post-Soviet economy became all about oil. They could get to it. They could transport it. And there was an insatiable worldwide demand for it. Things were looking up. Putin was popular. Luxury cars and iPhones became available, along with

Starbucks. Russia was back.

Enter “The Crisis”. Gas use plummets worldwide (who could have seen THAT coming?) The price of oil falls drastically. Imports falter. Exports falter. Even the economy of China, a country of billions of consumers at the doorstep of Russia, stumbles.

I returned to Perm in January 2009. Because I am American, I heard a lot of blame about “The Crisis”. Like Americans that I know, the people of Perm are concerned about their jobs and cautious about their spending. The ruble is in a tailspin, food prices are up, gas is $4 a gallon. There are even open protests against Putin’s economic policies.

I live in Kentucky and I’ve been hearing a lot about the devastation this economic tsunami has wrecked on rural Kentucky. I began wondering about the Russians that live outside of their cities. In the US, The “Crisis” seems to have hit people in smaller communities every bit as hard as those in the cities… maybe even harder. Jobs were already

scarce in rural America, even before this meltdown. To take a look at out how “The Crisis” was affecting people in rural Russia, I took a trip to the small village of Elova.

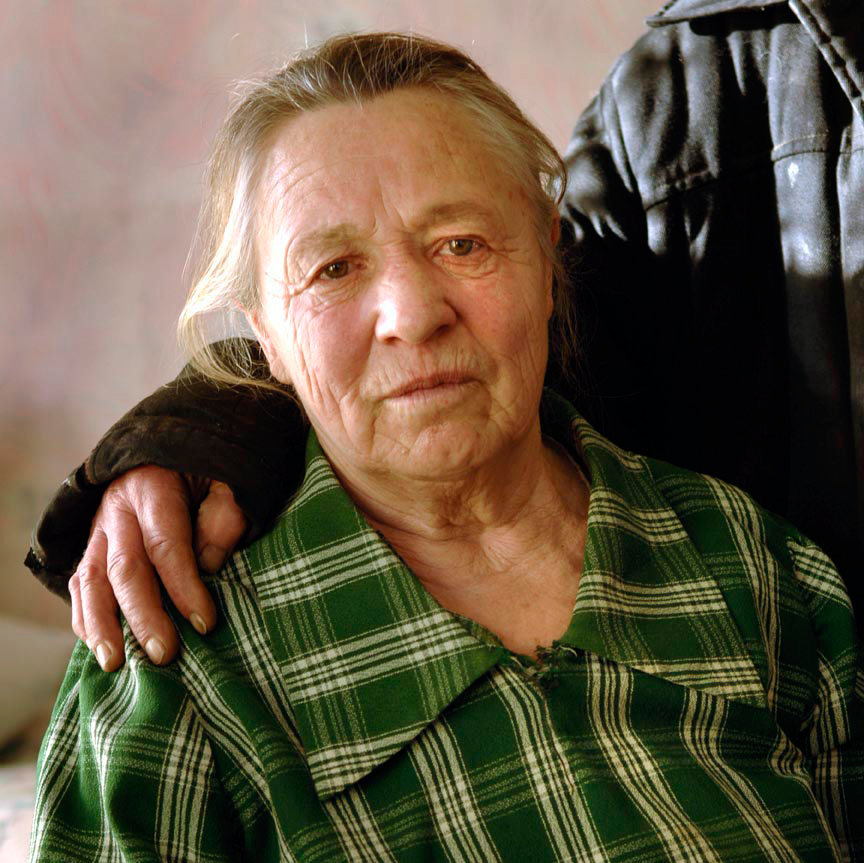

(Elova, Russia- No signs on the few stores lining the main road…few cars, orderly unpainted wooden houses. Stark dark wood against the white snow. Smoke coming from all of the chimneys, a child playing with a dog.) There I met Okulov Ivan Petrovich and his wife Okulova Olga Grigorievna. Not only had they never met an American, they had never met anyone from any other country. In their life they had traveled only as far as Perm, some 200km away. Ivan & Olga are in their mid 80s. They live in a small two room house… a kitchen and a bedroom/dining room, with a large stone stove in the center.

When I arrived, Ivan was outside in the minus 10 degree weather, knee deep in snow, chopping wood. The pile of wood was as tall as his five foot height. I’ve been told that the harsh weather of Russia made the people industrious, hard

workers. Russians couldn’t survive in their environment without constant hard work and that seemed true of Ivan & Olga. They had met as teenagers working in the communal fields of Stalin-era Russia. Ivan ran machinery that harvested grain and Olga did the work by hand. As we sat at the table, covered with homemade jams, borscht, black bread,

meat-filled dumplings called pelmeni and, of course, ice cold vodka, Ivan talked of Elova under Stalin. Their life was only about work, with little to eat. Russians of Ivan’s generation talk about friends dying of starvation, families dying of starvation. Sitting in another kitchen, I listened to a couple that had survived the Nazi siege of Leningrad. I watched

as the elderly woman pulled a small crust from the bread she had baked that morning.

Handing me the bread she said that this was all they would have had to eat, day after day. Sometimes they would steal a potato from the field, slipping it into a pocket.

These conversations put the present economic “crisis” in perspective for me. I asked Ivan, “How can you be in such good spirits, be so content, be so happy after living through all of that? He thought for a moment, smiled and said simply, “We have all we need”.

Olga & Ivan’s lifestyle in Elvoa represents the last vestiges of the communal life of Russian peasantry in which they grew up. The economy of the Soviet village didn’t involve much cash. They were sometimes able to sell regional crafts or clothing. But the commune was primarily about agriculture… growing enough during the summer to survive the long, cold winter.

Olga still puts out a large garden in the field next to their house…the vegetables shared by and bartered to their neighbors. This survival against the elements, survival against their government, the struggle to stay alive and sane toughened them. Today’s “Crisis” paled by any comparison.

After three or four shots of vodka, Ivan took me to a tiny outbuilding next to his house. Inside was Ivan’s workshop for making the traditional felt boots, valenki, still worn by elderly Russians. Ivan explained that when he was young he watched a 75 year old woman make the boiled wool boots.

He saw it done only once and then spent the rest of his life perfecting the process. The workshop was about 7×7 feet with a ceiling just high enough for me to stand. The room contained a small work table, a wood burning stove to boil the wool, a small window and a single bare light bulb. Handmade tools hung from the walls and ceiling. The room was incredibly hot, a large cast iron pot boiling on the stove.

Olga & Ivan used to raise the sheep themselves, but now, at their age they get the wool from someone else in the village. It’s a special gray/brown wool, high in lanolin. Olga starts the process in the house. Knowing just how much wool Ivan will need for the size of boot that he is making, she combs it until soft and pliable. In a process of boiling, then working by hand, then boiling some more, the boot begins to take shape. It takes an incredible amount of sweating, physical labor. Ivan rolls the wool, pushes the wool.

Every 5 minutes or so the lump of wool is wrapped with a leather strap and placed back in the boiling water. Slowly, using his wooden forms and much labor, the boot begins to take shape. Each pair of boots takes three days to make. Three days! Ivan tells me that one year he made 70 pairs. Ivan doesn’t sell many valenki anymore. The old Russians in the village already have theirs and the young don’t really want them. He recently made boots for three young children of the village, telling me, “How could I not make boots for children”?

Olga & Ivan seem unaffected by “The Crisis”. All economic problems seem far away, left back in the city. They don’t have much, but what they have is enough for them- a warm house, food on the table, their health, and each other. If I’m hearing it right, Russians of Ivan & Olga’s generation just want to be left alone by their government. They’re not starving, they’re not being sent to the gulag, they’re not being forced to work dawn to dusk for no reward, they’re not fighting in a war. They have enough. They have each other. There is no crisis in their world.

As I prepare to leave, we walk outside into the blowing snow. The day is turning crystal blue in the cold twilight. Olga proudly hands me a single, child’s valenki. It’s beautifully crafted, perfectly formed and smells of grain, of the earth. She apologizes that they don’t have a pair for me, as they only found out two days ago that I was going to visit. When I

come back, she tells me, Ivan will make the other boot for me.

Michael Brohm is a russophile. His interest in Russia started in grade school inthe 50s. He reads Pravda online, scans

the New York Times for articles on Russia, emails friends in Russia with questions. As a photographer, he has taken on a project in the Perm region of central Russia, making portraits of people from all walks of life. He has just returned from his 3rd trip to Russia.

the Feb/Mar Z (click the cover)

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.