Readers of the Zephyr are not unfamiliar with the angst that its writers often express over the deteriorating state of our natural environment and the ineffectiveness of our best efforts to reverse the trend. Attempts to correct the problem by fighting development or choking off the extraction of natural resources have proven to be ineffective, because the all-powerful industrial/commercial machine that feeds the insatiable appetite of human desire always finds a way to sustain itself. What the environmental activists rarely confront is the underlying psychology that drives this system. Simply put, it is our addiction to artificiality resulting from our compulsion to create the feeling that we have escaped from nature. Comfortable, non-natural surroundings, furnished with an ample supply of gratuitous, man-made objects, create in us the pleasurable, but tenuous, feeling that we have successfully transcended nature.

To secure the myth and prevent the light of reality from dawning on us, we bombard our senses with an endless array of unnatural stimulants. The irony of the situation is that most of the proponents of environmentalism seem to be no less enamored by artificiality than the rest of society, as evidenced by their lifestyles and deepest aspirations.

Although humans have taken a certain pleasure in artificial things since time immemorial, it was not until after the Civil War that our society fully embraced artificiality as the Great American Dream. The essence of this philosophical choice was best expressed by the celebrated Colorado River explorer, John Wesley Powell, who declared that success comes “not by adaptation to environment, but by the creation of an artificial environment.” He dismissed the ancient practice of adaptation to nature, as practiced by Native Americans and other minority cultures, as being primitive and archaic.

The fulcrum of the societal paradigm shift was the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which overtly promoted the theme of “progress”. Not intended merely for entertainment, the fair was “a propaganda of social ideas,” according to one of its architects. The glamorous, but flimsy, buildings that comprised the “Great White City” housed the fanciest examples of artistic and technological endeavor that humankind had to offer. Exposure to these items, it was hoped, would arouse the populous “from the apathy of a dull and colorless existence by any object lesson in the higher regions of human effort.” Older cultures, such as those of the Native Americans, were represented at the fair, but only to illustrate how far modern civilization had progressed from its primitive past.

The possibility that this shift in focus from the natural to the artificial would create a profound loss of wisdom seemed not to have crossed the minds of the social reformers of the day. A few Americans disagreed with the new approach, but they had no public voice in the matter.

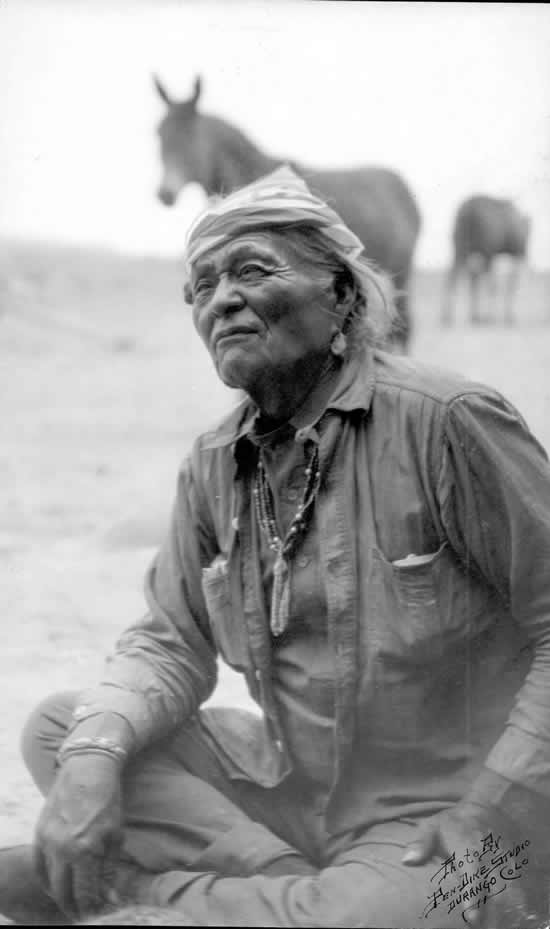

One man who knew better was a humble Navajo shepherd named Wolfkiller who lived in the rugged country of southeastern Utah. My great grandparents, Louisa and John Wetherill, first met him in 1906 at the isolated outpost of Oljato, near Monument Valley, where they moved to start a trading post. From all outward appearance, he was just a simple herdsman—curiously comfortable with his primitive way of life but unsophisticated in the ways of the world outside of his little section of the Utah desert. The Wetherills soon recognized that he was a unique personality who had a rare understanding of life.

Years earlier, Wolfkiller’s grandfather and mother had taught him how to follow the “path of light” by studying nature and to adapting his feelings to its ways. Wolfkiller recounted to my great grandmother the lessons of his youth and how they helped him through later times of adversity. Louisa translated and recorded his stories, which they both hoped to preserve for the benefit of future generations. Several years ago I ran across the manuscript in the family archives. It was finally published in 2007 under the title, Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd (Gibbs Smith Publishers).

Wolfkiller received his first lesson in the wisdom of nature in the early 1860s when he was about six years old. His grandfather overheard him complaining about the icy wind and gently explained that it was something to be thankful for. “All things are beautiful and full of interest if you observe them closely and study them,” the grandfather admonished. After considering this advice for a few days, Wolfkiller came to see that the wind is good. “We had thought the wind was just a useless thing to cause us unhappiness, but now we saw that it had many purposes. It cleared the air of the odors of decaying plants and dead animals, brought the clouds on its wings to give us rain, and made us strong,” he concluded.

When a violent rain and lightning storm terrified the young boy, his grandfather took him out to study the aftermath. “See how beautiful it really is,” said the grandfather. “How black the clouds are. See the streaks of white lightning coming down. See the rocks over which it has passed—how they glisten. And you can see how fresh and green the cornfields, grass, and trees are now. We needed the storm to make things beautiful.”

When winter came again, Wolfkiller’s mother asked him to go outside and roll in the snow. “The snow will be with us for several moons now, and if you roll in it and treat it as a friend, it will not seem nearly as cold to you,” she explained.

Wolfkiller’s elders were not mere fair-weather lovers of nature. They relished their intimate connection with the earth and valued the wisdom it offered so highly that their harsh living conditions seem trivial to them. Wind, cold, storm, and even natural death, caused them little concern. Wolfkiller learned that nature is not evil, but people sometimes respond to it in evil ways.

To those who have learned the ancient skill of adaptation, extreme environmental conditions can cause some discomfort, but they are rarely life threatening. The threat that they pose to America’s citified masses seems to be more psychological than physical. We have lost both the will and the strength to thrive under harsh conditions, because we have made a practice of molding nature to suit our whims rather than adapting our desires to nature’s ways. On a deeper level, our fanatical pursuit of comfort amounts to a futile endeavor to transcend nature, and it only drives us to ever-increasing levels of self-deceit.

America’s quest for the artificial has led to the creation of a monster social, commercial, and industrial system that feeds upon itself and takes its due toll on the health of the earth, as well as on the souls of its adherents. We cherish technological innovations that serve no other purpose than to further distance us from nature. We idolize and envy the wealthy and glamorous because they have been the most successful at creating their own unnatural realms. Charity is helping others avoid nature. Many people now spend their entire lives with little exposure to nature at all. This obsession is so universally accepted by our society that we find it difficult to consider that an alternative even exists.

From ancient times, contemplative people have looked to nature for essential insights about life. The scriptures are full of proverbs and parables of those who were keen observers of nature and understood the deeper implications of their experiences. One such lesson is that a profound problem cannot be solved superficially—it must be attacked at its root. The ills of the environment will never be cured by those who are themselves dedicated to the pursuit of artificiality and lack the wisdom to see the dichotomy between that goal and their wishes for the health of the earth.

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.