MOAB IN THE 60s

After the tumultuous decade of the 1950s–the Charlie Steen Decade–Moab and Grand County slowed down a bit. In 1960, Grand County’s population had tripled in ten years, to more than 6000, and the more optimistic of that population thought the Big Boom might go on forever. It sounds a bit like 21st Century Moab promoters who think the curve will never flatten or descend. But it always does. Mining and oil production still fueled the economy, but by the end of the Sixties, tourism came to be regarded as a viable alternative to the traditional extractive industries; very few could see the extractive nature of tourism itself.

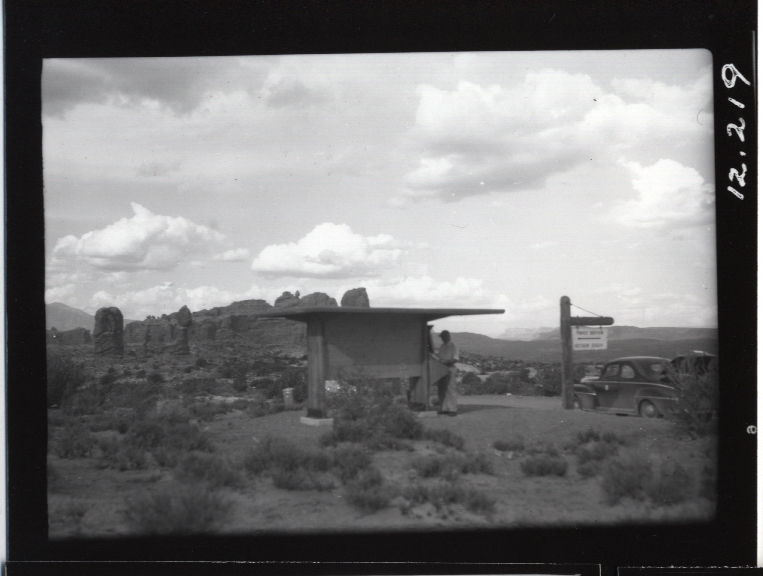

Arches National Park was transformed in the late 50s and early 60s by a massive federal project called Mission 66. Visitation to national parks across the country skyrocketed after World War II and the infrastructure of the parks was considered grossly inadequate by the bureaucrats in Washington. President Eisenhower proposed and the Congress approved a huge infusion of funds that provided new roads and visitor centers and campgrounds at scores of parks and monuments; Arches was one of them.

Until 1958, a single dirt road entered the monument near the Deadhorse Point turnoff, from what is now US 191. The road forked at Balanced Rock and spur roads led to Wolfe Ranch and the Devils Garden. The “improvements” were completed in phases, but by 1963, 21 miles of new paved highway, a visitor center, and a campground equipped with running water and “Comfort Stations” were completed. Annual visitation to Arches had hovered around 25,000 prior to the construction. Within a year of completion that number exceeded 100,000 and has been rising ever since (2002 visitation approached 900,000).

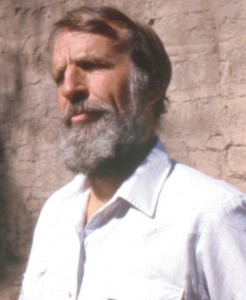

One of the very few to object to all this good news in the late 50s had been Arches seasonal ranger Edward Abbey. No one paid much attention to his laments at the time, and after the 1957 season Abbey left Arches in disgust. But in 1965, Ed Abbey came back to Arches for a third season, despite the new roads and bunkeresque visitor center and, as he put it, “…was better able to appreciate the changes that had been made in my absence.”

One of the very few to object to all this good news in the late 50s had been Arches seasonal ranger Edward Abbey. No one paid much attention to his laments at the time, and after the 1957 season Abbey left Arches in disgust. But in 1965, Ed Abbey came back to Arches for a third season, despite the new roads and bunkeresque visitor center and, as he put it, “…was better able to appreciate the changes that had been made in my absence.”

Bates Wilson had been superintendent of Arches National Monument since the late 1940s. But for a decade Bates had campaigned on behalf of that vast and spectacular acreage across the road–the redrock “standing up country” that many called “canyonlands.” Bates found an ally in the new Secretary of the Interior, Stuart Udall, who made several trips in the 60s into the slickrock with Bates, along with interested local citizens, Park Service administrators, and other politicians. The debate was intense at times and rancorous. Locals feared the new park would eliminate their livelihoods, which in 1964 were still rooted in mining and ranching. The size and scope of the park was scaled back repeatedly and NPS plans to build a labyrinth of new paved roads was revealed and promoted as a means of reducing opposition. Even then, the commodification of Nature was apparent. Marketing the beauty of the land was in its infancy, but rapidly gaining a foothold in the economy of the Rural West.

In 1964, Canyonlands National Park was created by an act of Congress and Bates was appointed its first superintendent. His generous nature and his ability to resolve conflicts helped ease the transition for southern Utahns. Many locals almost thought of the new creation as Bates’ Park, and many animosities and disagreements over the administration of the new park did not crystalize until after Bates Wilson’s retirement in 1972.

While SE Utahns debated the emerging importance of tourism, Moab’s most prominent citizen left town. Charlie Steen, the Uranium King, who literally transformed Moab almost overnight with his uranium discovery in 1952, announced his imminent departure. Charlie had been elected to the state legislature, but ran into a very hard wall when he introduced bills to reform liquor laws. This was, after all—Utah. Frustrated and angry, the Steens left Moab and moved to Nevada, where the tax structure was also more favorable to one of the richest men in the country. The citizens of Grand County were shocked by his sudden exit, and from that day, the Legend of Charlie Steen has rooted itself firmly in the pop history of Grand County.

Despite Charlie Steen’s farewell, mining continued to play an integral role in the economy. Texas Gulf Sulphur began construction on a railroad spur line from Crescent Jct. to its new potash plant along the Colorado River. The price of uranium rose and fell as the decade proceeded, but by the late 60s growing opposition to nuclear power and concerns about its safety seriously affected mining and its processing in SE Utah. Other projects, however, continued to provide jobs and revenues for the county.

The Interstate Highway System, introduced in the 1950s by Eisenhower, now reached into southern Utah. I-70 would follow the route of US 6 from the Colorado border to near Green River; beyond that small town, however, the interstate highway would enter virgin territory. The new highway would be blasted out of the sandstone flanks of the San Rafael Swell and ultimately connect with I-15, more than 150 miles west. The project would take almost 30 years to complete.

In 1963, at Green River, a missile base was proposed and very rapidly constructed on the east side of the river, in Grand County. With the Cold War alive and well, and just months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the project was approved with little or no public opposition. Missiles were fired from the Green River base and targeted to the White Sands Missile Complex in New Mexico. Until the early 1970s, portions of Canyonlands National Park were closed by rangers to eliminate the risk to tourists of falling booster rockets and errant missiles.

Goofy ideas have always been a part of Moab’s history–past and present. In the early 60s, proponents of a series of dams on the Colorado River were still active, even as Glen Canyon dam was being built, 200 miles downstream. The Bureau of Reclamation’s dream of controlling every mile of the Colorado River died when opposition to damns inside Grand Canyon National Park received national attention. But it was too late for Glen Canyon. In early 1963, the diversion gates at the dam were closed and sealed, and the free-flowing river died. At least for now.

For those Grand County residents who remember the battle to stop a proposed highway over the Book Cliffs to Vernal in the early 90s might be surprised to learn that the same fight was waged in the mid-60s. Support for the road had seemed solid, but in 1966 the Ute Indian Tribe withdrew its permission for the road to cross its land; eventually even ranchers and sportsmen opposed the project and the idea lay dormant for 25 years.

And finally, in 1967 the idea of “Fort Moab,” a tourist theme park to be located just north of town, was bandied about, but never went anywhere. They were just a bit too early.

In 1968, a Marine pilot from Moab was lost in action in Vietnam. He would not be the last. In Richard Firmage’s otherwise excellent History of Grand County (to which I referred frequently while writing this story), he writes: “Grand County did not experience much, if any, counter-culture social unrest or protest during the latter part of the 1960s.” That was simply not true, although it might have been difficult to find any public mention of it in the local paper. Sentiment for and against the war was intense at times, but opinions from both sides of the aisle were frequent.

Lyndon Johnson’s last hurrah as president ruffled some feathers in Moab, when the lame duck president signed a proclamation dramatically expanding the boundaries of Arches National Park. He signed the document just a few minutes before leaving for the capitol and the inauguration of Richard Nixon. Some locals complained bitterly; the expansion brought all of lower Courthouse Wash and the Petrified Dunes under Park Service control. When the NPS closed the wash to vehicles (much as it has recently done at Salt Creek in the Needles), jeepers were livid. Ultimately however, the crisis passed.

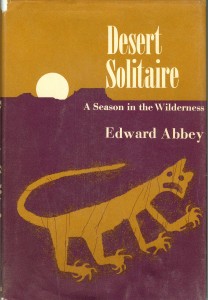

A year before President Johnson’s final act, McGraw-Hill published a modest book of essays by a relatively unknown writer. If the term environmentalist had even been coined in 1968, Edward Abbey would have been called one. Desert Solitaire received a smattering of good reviews. Joseph Wood Krutch called Abbey “eloquent, bitter and extravagant,” and called his book “a passionate celebration.” A.B. Guthrie wrote, “Only the damned engineers, the Bible pounders, the chambers of commerce and the proudly prolific studs and dams will fault this book. There are quite a few of us who will answer to its sensitivity, its style, its stout thought and its downright honesty.”

A year before President Johnson’s final act, McGraw-Hill published a modest book of essays by a relatively unknown writer. If the term environmentalist had even been coined in 1968, Edward Abbey would have been called one. Desert Solitaire received a smattering of good reviews. Joseph Wood Krutch called Abbey “eloquent, bitter and extravagant,” and called his book “a passionate celebration.” A.B. Guthrie wrote, “Only the damned engineers, the Bible pounders, the chambers of commerce and the proudly prolific studs and dams will fault this book. There are quite a few of us who will answer to its sensitivity, its style, its stout thought and its downright honesty.”

There weren’t that many at first and the hard cover version faded into history after one printing. But it was released in paperback a year later, and slowly, year after year, thousands of young men and women found their way to the words that would change many of their lives. In the decade to come, the crusade to save the canyons would have far-reaching implications, even into the 21st Century. For some, at least, that crusade would prove to be bittersweet.

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.