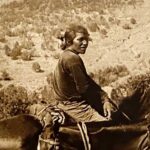

From early times, a tiny community of Paiute Indians made their homes at the bottom of a remote canyon that transects the Arizona/Utah border. Early in 1909, two of them—a father and son—rode eastward on a rocky, fifty-mile-long trail toward Monument Valley in order to patronize a trading post at a place known as Oljato. The father’s name was Mupuutz, which means “Owl” in the Paiute language, although he was better known by the Navajo translation of his name, Nasja (Nd’dshjaa’), or the name the census takers used for him, Ruben Owl. His son was called Nasja Begay (Nd’dshjaa’ Biye’), i.e., Owl’s Son. Nasja was in his early seventies, and Nasja Begay was about eighteen.

The pioneer trading post at Oljato had been established a few years earlier by John and Louisa Wetherill, my great-grandparents, and Clyde Colville, their trading partner. They were quite fluent with the Navajo language and were learning some Paiute as well.