In The Affluent Society, John Kenneth Galbraith suggests that the field of Economics has not sufficiently evolved to account for widespread material abundance, which is itself a recent condition anywhere in the world. Galbraith argues that the affluent society is different in kind, not just degree, from the generalized deprivation that prevailed for most of human history. He further argues that one of the more significant and troubling features distinguishing the affluent society is the pervasive manufacture of consumer demand.

Galbraith introduces the point in the first chapter of The Affluent Society: “One would not expect that the preoccupations of a poverty-ridden world would be relevant in one where the ordinary individual has access to amenities — foods, entertainment, personal transportation, and plumbing — in which not even the rich rejoiced a century ago. So great has been the change that many of the desires of the individual are no longer even evident to him. They become so only as they are synthesized, elaborated, and nurtured by advertising and salesmanship, and these, in turn, have become among our most important and talented professions. Few people at the beginning of the nineteenth century needed an ad-man to tell them what they wanted.”

A longer passage lays out a key insight into the work of the modern “ad-man”:

“If the individual’s wants are to be urgent they must be original with himself. They cannot be urgent if they must be contrived for him. And above all they must not be contrived by the process of production by which they are satisfied. For this means that the whole case for the urgency of production, based on the urgency of wants, falls to the ground. One cannot defend production as satisfying wants if that production creates the wants.

Were it so that a man on arising each morning was assailed by demons which instilled in him a passion sometimes for silk shirts, sometimes for kitchenware, sometimes for chamber pots, and sometimes for orange squash, there would be every reason to applaud the effort to find the goods, however odd, that quenched this flame. But should it be that his passion was the result of his first having cultivated the demons, and should it also be that his effort to allay it stirred the demons to ever greater and greater effort, there would be question as to how rational was his solution. Unless restrained by conventional attitudes, he might wonder if the solution lay with more goods or fewer demons.

So it is that if production creates the wants it seeks to satisfy, or if the wants emerge pari passu [concurrent] with the production, then the urgency of the wants can no longer be used to defend the urgency of the production. Production only fills a void that it has itself created.”

Marketing’s capacity to spark and fan the flame it promises to quench has only grown in sophistication since The Affluent Society was published 61 years ago, and part of this evolution has been the selective merger of political and commercial agendas, including, notably, by many self-proclaimed subversives and revolutionaries. A few astute social critics have noticed. In 1997, with an apparent nod to the concept of “manufactured consent” made famous by Noam Chomsky, The Baffler published Commodify Your Dissent, which is a collection of essays cataloguing many of the ways in which the counterculture creates late capitalism and vice versa.

One prominent example is the trope of the “rebel” consumer, in which choosing a given brand is conflated with revolutionary political action or is carefully deployed toward the formation of an “alternative” or transgressive social identity. In this move, shopping becomes an integral part of the process of self- and meaning-making.

Naturally, the rebel consumer is mirrored by the rebel corporation which eagerly co-opts countercultural totems to sell, say, Chryslers. This has led eventually to a marketing race away from superficial gestures and toward signals of authentic corporate virtue; we now see many companies which don’t merely traffic in “woke” social or political symbols, but explicitly take on a capacious social and political identity. It’s as if, in Romneyian parlance, corporations really are people, my friend.

To complete the picture, a new figure has emerged at the helm of many of these organizations: the corporate leader who merges master-of-the-universe, robber baron-scale corporate ambitions with political-aesthetic sensibilities that would be at home in the Beatnik 50s or Free Love 60s. These characters score off the charts according to Bobo math: to calculate a person’s status, take their net worth and multiply it by their antimaterialistic attitudes. A fitting name for this odd new lifestyle-leftish corporate orthodoxy might be Countercultural Neoliberalism.

Given this state of affairs, it should come as no surprise that the culture wars are absolutely fantastic for business, especially as political polarization has amped up in the last decade or so. Everything from the running shorts we wear to the chicken sandwich we eat has been successfully enlisted in the cause. What cause, you may ask? The cause, of course!

It doesn’t always go according to plan. Sometimes the wires show and it comes off as clunky or worse, as in the Kendall Jenner-Pepsi debacle. But often it works seamlessly, and the well-heeled, well-coiffed fakerjack is invented (for example).

We also, of course, get the New West, where there’s always a bumper to sticker with a cause célèbre, where there’s always a new Best Town to colonize, and where hell is other people’s fossil fuels.

The New West is also where virtually every successful company that comprises what we might call the Recreation Industrial Complex (RIC) now primarily sells sanctimony and only secondarily sells the good or service that keeps its owners and executives well-fed. In a way, it’s an ingenious twist on Robinson Crusoe: we should speak only of our arduous journey toward self-actualization but, yeah, by the way, we also happen to be fabulously wealthy thanks to the Brazilian plantation we own.

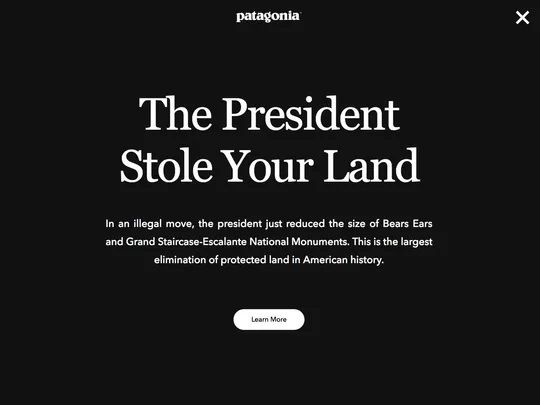

In canyon country, specifically, we can observe how the RIC manufactured both the demand for “Bears Ears” and the satisfaction of that demand. In statistical terms, approximately no one seemed to need to visit “Bears Ears” before December 2016, but now every outdoor athlete with a shoe contract and a Personal Brand to burnish — an “influencer” in the postmodern vernacular — seems determined to make an Insta-pilgrimage to “Bears Ears” or to at least engage in a bit of slacktivism from afar. The hoi polloi cannot be far behind.

It certainly cannot be said with a straight face that the urgency to both produce and consume “Bears Ears” originated with any of the thousands of people who had never heard of it before it showed up in their social media feed thanks to their status as “follower” of their preferred gear manufacturer (and who immediately felt sufficiently well-informed to voice their very strong opinion on the matter).

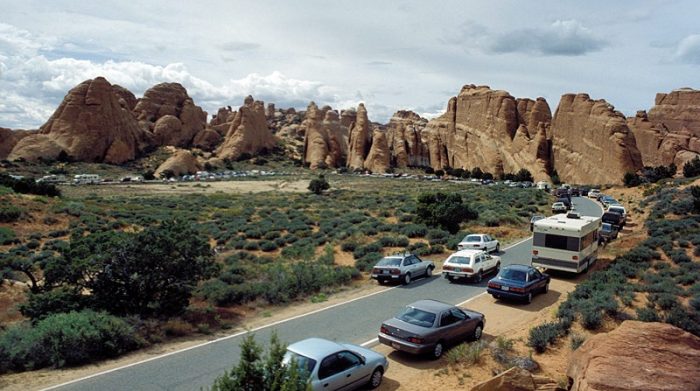

And finally, also in canyon country, we can look at Moab or Springdale or Torrey and see the logical endpoint of the counterculture-neoliberals’ unflinching manufacture of demand for evermore New West.

In Moab, for instance, a prospective reservation system to cope with the overtourism of Arches is apparently being met with measured suspicion from some locals thanks to its potential for sucking $22 million from the Moab economy. Shuttle systems like the one that operates in Zion are another popular half measure for managing absurd levels of tourism. And still another commonly invoked solution is to move more off-brand public lands into tourism’s prime time lineup (usually through the sweeping and politically toxic use of the Antiquities Act).

But beneath a thin veneer of environmental sensitivity, these still are neoliberal growth schemes in practical effect. After all, such measures only get broad support in the New West if they merely smooth out the lumpiness of visitation across time and/or space, and pave the way for more net growth in the long term. Such support immediately evaporates if the wrong ox is at risk of being gored. “Believe in something even if means sacrificing everything” indeed.

In truth, it has never been more clear that New West orthodoxy revolves around certain sanctioned forms of conspicuous leisure married with an ostentatious yet cost-free performance of wokeness. Low forms of recreation have no place here. The same goes for work, especially stereotypically blue collar work, which is only properly done by suckers, the voluntarily poor, and the occasional moneyed neo-Thoreau anyway.

It’s all great for getting clicks, and even better for moving units, pleasing the donor class, and getting out the vote. It is also nearly enough to make a cynic wonder along with Galbraith whether the solution to what pains the affluent lies not in more goods, but fewer demons.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Thank you for this brilliant analysis of The Age of Cui Bono. I live in Flagstaff. Say no more. Instagram “see me” posters brought hordes in to slaughter the California wild poppy fields. This winter, I was unable to drive to a friend’s near the Canyon, because the highway was clogged with “snow-play” invaders – the only good news is that more than a few of them ignored their kids wandering in the road. Money, six seconds of cyberFame, being in a Name Brand spot, our species is cancer.

Fabulous analysis–and so true. As a Boulder resident of almost 40 years, I’ve watched our counter-culture oasis turn into Aspen Junior, Silicon Valley East. Then we did it to Moab… but it seemingly happened everywhere all at once. I haven’t been to Torrey in many years–I didn’t realize it had succumbed as well. I didn’t need any advertisement to fall in love with the West. The movies did the trick.

There were no greater advertisements for the West than John Ford’s movies. Indeed, the list of filmmakers who featured western landscapes are legion…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Western_(genre)_film_directors

A great analysis showing how heavy handed materialistic corporate manipulation molds the future of The West. Recreation’s smoke and mirrors is a poor substitute for real life in the West and those who love living and working there.

Thanks for the article and the opportunity to comment.

One example of the sanctimony of the RIC that comes to my mind is demonstrated by Mr. Chouinard’s company, Patagonia. Mr. Chouinard stands to profit as much as anyone from the exploitation of the wide open spaces. His business is outfitting all of us so we can go out and run rampant across the land we cherish so much. Old Mr. Folksy stands there in his blacksmith’s apron, yuk, yukking like a hayseed, when in fact he’s got a couple hundred million bucks in the bank.

Patagonia’s various advertisements are somewhat disingenuous when they say “…the land belongs to all of us…not to those who would profit at the expense of the wild places that we all cherish more than almost anything else in this world.” The fact is, Patagonia profits from selling outdoor equipment, and has a vested interest in keeping as many people as possible roaming the landscape. Having land tied up by other interests such as mineral exploration, ranching, farming, etc., is antithetical to its business model.

Unless I am mistaken, the Federal Government receives royalty fees from leases on public lands. Some of the money received, I presume, goes toward management expenses of those public lands: Federal agency employee salaries and benefits, facility and equipment purchase and maintenance, trail and road maintenance, sanitary facilities upkeep and maintenance, trash pickup, search and rescue operations, and on and on. Here’s an idea: Let’s have Patagonia (and all other suppliers of recreational equipment and the RIC in general) pay a portion of their revenue into an escrow account dedicated to the maintenance and upkeep of the public lands that their customers are using virtually “for free” at our nation’s taxpayer’s expense. Maybe a user fee or tax on outdoor goods and services, collected at the register and paid for by Patagonia consumers, should be instated and channeled to the upkeep and maintenance of public lands.

Brilliant essay.

One could write volumes on the hypocrisy of the RIC. The perfect anecdote: I somehow ended up on the REI email list and got an email asking “Can you ever have enough gear?” This mere weeks before REI’s boss asked us all to opt out of Black Friday and go outside.

And thank you for pointing out Galbraith’s argument about production inducing demand, an idea that goes back way further to Marx and actually to the “bourgeois” political economists whom he critiqued and from whom he liberally (radically?) borrowed. A good metaphor to supplement this idea is that of the “shifting baseline,” taken from lanscape architecture and ecology (Daniel Pauly, thank you!) Each new generation “forgets” (or never knew) what came before, so has little sense of what the “old west” (whatever it was) was like. I’m sure that someone arriving in Boulder 40 years ago finds today’s boulder with its Elk Steaks over Organic Carrot Puree (pretty good, actually) at the Hell’s Backbone Grill and Aesthetic-Ecological-Conscience-Salving-Experience rather spoiled. But I wonder what the ranchers thought of the counter-culture’s arrival, it too spurred on by advertising and consumerism far more than it wishes to admit, in the sixties and seventies?

Sadly, the desire to keep it “like it was”, as Saint Ed advocated, is tainted from the get-go by the very logic of desire that Galbraith points to.

I think back to my first sojourn the canyons of Utah as an 18 year old in 1983. For nearly a month me and my Outward Bound class (boy did I fall for those glossy brochures!) toodled through Canyonlands and adjacent country without seeing a soul. Moab was tiny, as I recall. Ah, that was the real west! We were aware that ranchers and miners and loggers were not far away–we knew they were a threat, but we didn’t see them. We pulled up their survey stakes. Etc.

But we were unaware that we were a vanguard in a movement that would lead to what we have now in southeast Utah. I’ll never forget the sadly very slight cognitive dissonance I experienced when I learned that our course leader, whom I idolized, was spearheading OB’s ventures into corporate training. He went on to be very successful at that on his own, dragging the elite to Canada and Alaska and Utah to learn team building. But it was also part of a far larger historical movement that would drag the outdoors so fully into the circuits of capitalist “valorization.” (…)

At my age, I can recall a “purer” time in Canyonlands–a very important time in my life–that was already so tainted. The people living the “real life” in the west are perhaps forgetting the real life that was displaced for that real life….

Alas.

I’ve taken my kids to Utah. They loved it. They didn’t care that 128 people were in Spooky Gulch with us and it literally smelled like perfume. They don’t think twice about the people I rail about with their cell phones and headphones and bluetooth speakers at Hatch Point or, worse, hiking by the dozen on a trail I thought was just a sheep track back in 1983. The baseline has shifted, for sure.

Somehow we have to think about the “New West” without succumbing to nostalgia for a pure time that didn’t exist.

Thanks for this article. It’s brilliant. Worth repeating.

Chris,

Great comments, you said so much that mirrors my thoughts on this subject as well. I came much later to Moab than you, and yet feel very fortunate that I was able to experience it for the first time in 1999. When I was in town in November, 2017 and saw – for the first time – the new 3 story hotel across the street from the Uranium Building my broke. The town will never be the same I’m afraid.

It’s with guilty pleasure that I return to Moab time and again for I descend upon it along with all the other entitled locusts to “go do our thing”, constantly aware that I am part of the problem, impacting a fragile desert ecosystem, and stressing it past its carrying capacity….

“In canyon country, specifically, we can observe how the RIC manufactured both the demand for “Bears Ears” and the satisfaction of that demand. In statistical terms, approximately no one seemed to need to visit “Bears Ears” before December 2016, but now every outdoor athlete with a shoe contract and a Personal Brand to burnish…seems determined to make an Insta-pilgrimage to “Bears Ears”… The hoi polloi cannot be far behind.”

Called this one, that’s for sure.

And now with Bears Ears restored, the hoi polloi have made it their mission to check it off their bucket lists, trample it, defecate in it, and force the BLM to alter its character to accommodate the hordes. No longer a primitive wilderness, Bears Ears has become the must-see attraction for the RV crowd who dare not venture far from camp.